George Martin was a music producer in London, on the prowl for rock ’n’ roll acts in the early 1960s, when he came across a band that had been turned down by every record company in town.

He wasn’t bowled over by the demo tapes, but, as he later recalled, “there was an unusual quality of sound, a certain roughness that I hadn’t encountered before....something tangible that made me want to hear more, meet them and see what they could do.”

A month later, Martin offered the group a contract. So began his long relationship with the Beatles.

As arranger, orchestrator and occasional player later in the group’s career, Martin was responsible for some of the landmark moments of ’60s rock: the swelling symphonic buildup and the lingering last chord of “A Day in the Life,” the delicate, harpsichord-like piano on “In My Life,” the string arrangement for “Yesterday” that signaled the group’s expanding ambitions.

Martin, who died peacefully in his sleep Tuesday at 90, produced nearly all the Beatles’ recordings, advising them on songwriting and arranging and capturing the vitality of their early performances in the studio.

But his crucial role may have been translating the sometimes hazy, poetic orders of the musically unschooled Liverpudlians into finished products.

That often entailed pushing the envelope. When John Lennon asked for a swirling, circus-like feel on “Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite,” the traditionally trained producer was bold enough to snip a tape of Victorian steam organ music into foot-long pieces, toss them in the air, then reassemble them randomly into a piece that fulfilled Lennon’s vision.

“John was pretty off the end at that time,” says Chris Carter, the host of the long-running radio show “Breakfast With the Beatles.” “Things like ‘Strawberry Fields’ and ‘I Am the Walrus’ were so out of left field musically — still brilliant, but they needed to be put into some context.... Without Paul [McCartney] and George Martin, the brilliance of those songs might have never been heard.”

::

Artistically, Martin had shown an open mind and a taste for experimentation long before he met the Beatles, notably on the comedy and novelty recordings he made in the 1950s and early ‘60s with the cream of Britain’s comedians, including Peter Sellers, Spike Milligan, Bernard Cribbins (the novelty hit “Right Said Fred”) and Peter Ustinov.

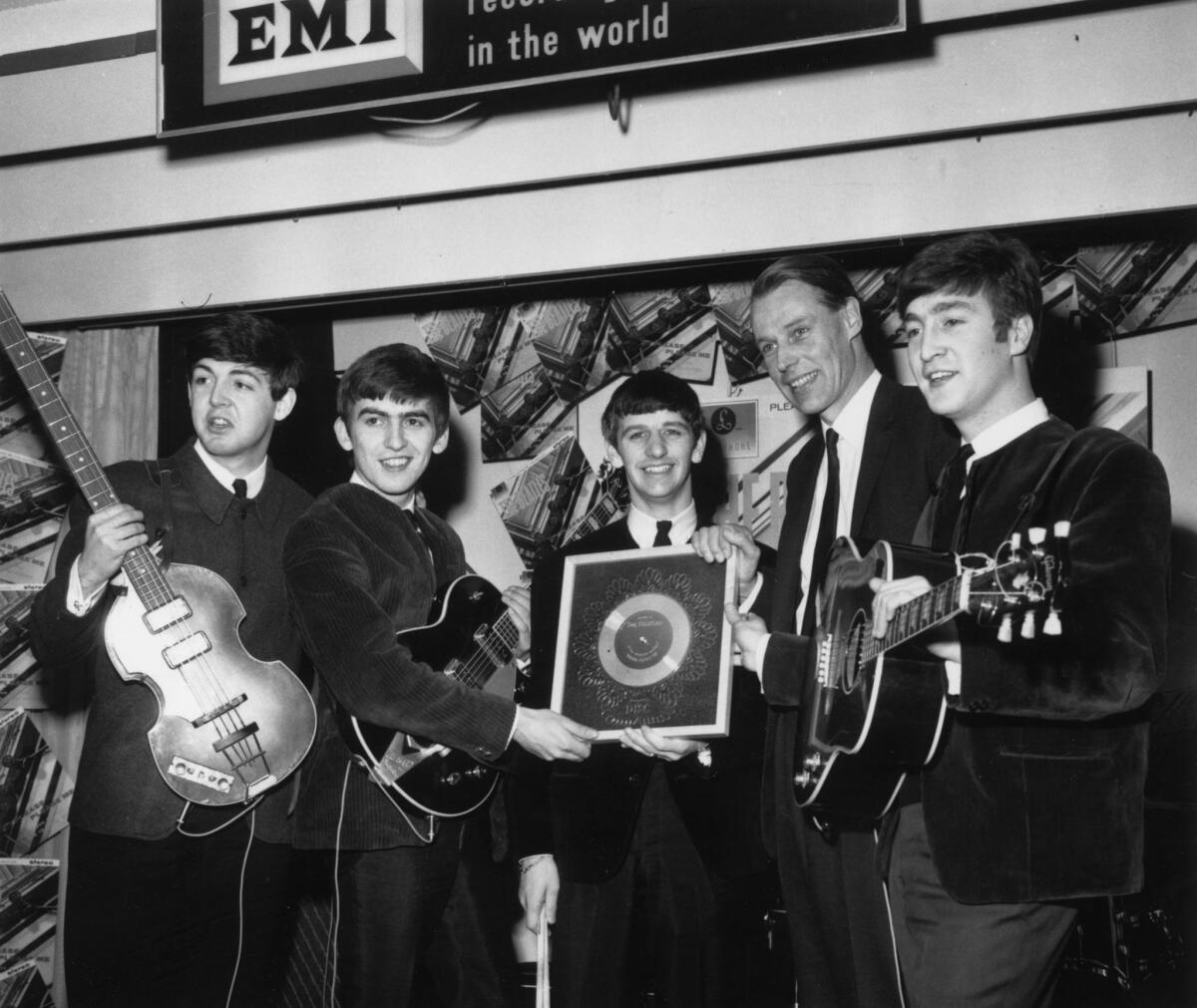

That background with some of the Beatles’ comedic heroes impressed the young band when their manager, Brian Epstein, contacted Martin, head of the EMI-owned Parlophone label, in April 1962. But they were eager to sign in any case, having been turned down by every record company in London — including other EMI labels.

Their first encounter, for a recording test at EMI’s Abbey Road studios on June 6, 1962, sealed the deal. Martin still had reservations about their talent, especially their songwriting, but he found them irresistibly charismatic, and the following month he offered them a contract.

“There’s no doubt that as things had worked out for them, I was the last chance,” Martin wrote in his 1979 autobiography, “All You Need is Ears.” If the deal hadn’t been made, he speculated, “possibly they would have just broken up, and never have been heard of again.”

::

George Henry Martin was born in London on Jan. 3, 1926, and grew up in the city’s Drayton Park district. The two-room flat where he lived with his parents and older sister lacked electricity and running water, and his father struggled to find work as a carpenter during the Depression.

They did have a piano, though, and Martin was fascinated with the instrument. He took lessons briefly, then continued to learn on his own. He had perfect pitch and a natural aptitude, and was soon able to play Chopin pieces by ear. Eventually, Debussy and Ravel became his favorite composers.

Share your memories of George Martin on our Facebook page>>

While attending school in Kent, Martin played foxtrots and pop standards at dances in a band called the Tune Tellers. He had dreams of composing for films, but when he finished school he went through a few jobs and then enlisted in the Royal Air Force in 1943.

World War II ended before Martin saw any combat. He returned to civilian life in 1947.

Using a veteran’s grant, Martin enrolled at the Guildhall School of Music in London and studied composition, piano and oboe for three years. He had few prospects when he finished and was working as a clerk at the BBC Music Library when he was offered a job as assistant to Oscar Preuss, the head of Parlophone Records.

Preuss was trying to revitalize the once-prominent company, and Martin was put in charge of the classical division, learning the basics of recording on the job as he oversaw sessions by the London Baroque Ensemble and other orchestras.

Martin also presided over Parlophone’s jazz acts and Scottish artists and eventually was doing almost everything at the company, which was still the poor relation among EMI’s family of labels. When Preuss retired in 1955, Martin was named to succeed him, becoming, at 29, the youngest person ever to run a major record company in England.

Desperate to establish a distinctive identity for a firm he characterized as “a tinpot little label,” he found his footing in theatrical comedy. Live recordings of the musical duo Flanders and Swann’s show “At the Drop of the Hat” and of Cambridge performances by the Beyond the Fringe troupe became big successes.

Martin followed with albums by Sellers and Milligan, often encountering sonic challenges that forced him to become an inventive manipulator of tape and a resourceful experimenter. When the sound of a beheading was needed for a Sellers recording, Martin sent out for cabbages and chopped them in front of the microphone.

Martin’s first No. 1 record at Parlophone was “You’re Driving Me Crazy” by the 1920s revivalists the Temperance Seven, in 1961. But his entry into the new world of rock ‘n’ roll was spotty. He passed on Tommy Steele, who went on to major pop stardom in Britain, though he did get some hits with Steele’s backup group the Vipers

Martin’s first session with the Beatles, on Sept. 11, 1962, yielded “P.S. I Love You” and “Love Me Do” (there were two versions of the latter, one with a drummer Martin had hired and one with the band’s brand-new member, Ringo Starr).

“Love Me Do” reached No. 17, and although Martin was convinced that the Beatles could be a hit, he still felt they needed better material. He insisted they record a song by Mitch Murray called “How Do You Do It?” and challenged them to come up with songs that were as good.

They responded with “Please Please Me,” which came out in January 1963 and quickly topped the charts. (“How Do You Do It?” wasn’t released until 1995, when it was included on “Anthology 1,” though the song became a hit for Gerry & the Pacemakers in 1963.)

For their debut album, Martin and the group selected 13 songs from their live set and recorded and mixed them in one 13-hour session. The album, “Please Please Me,” went to No. 1, and Beatlemania had begun.

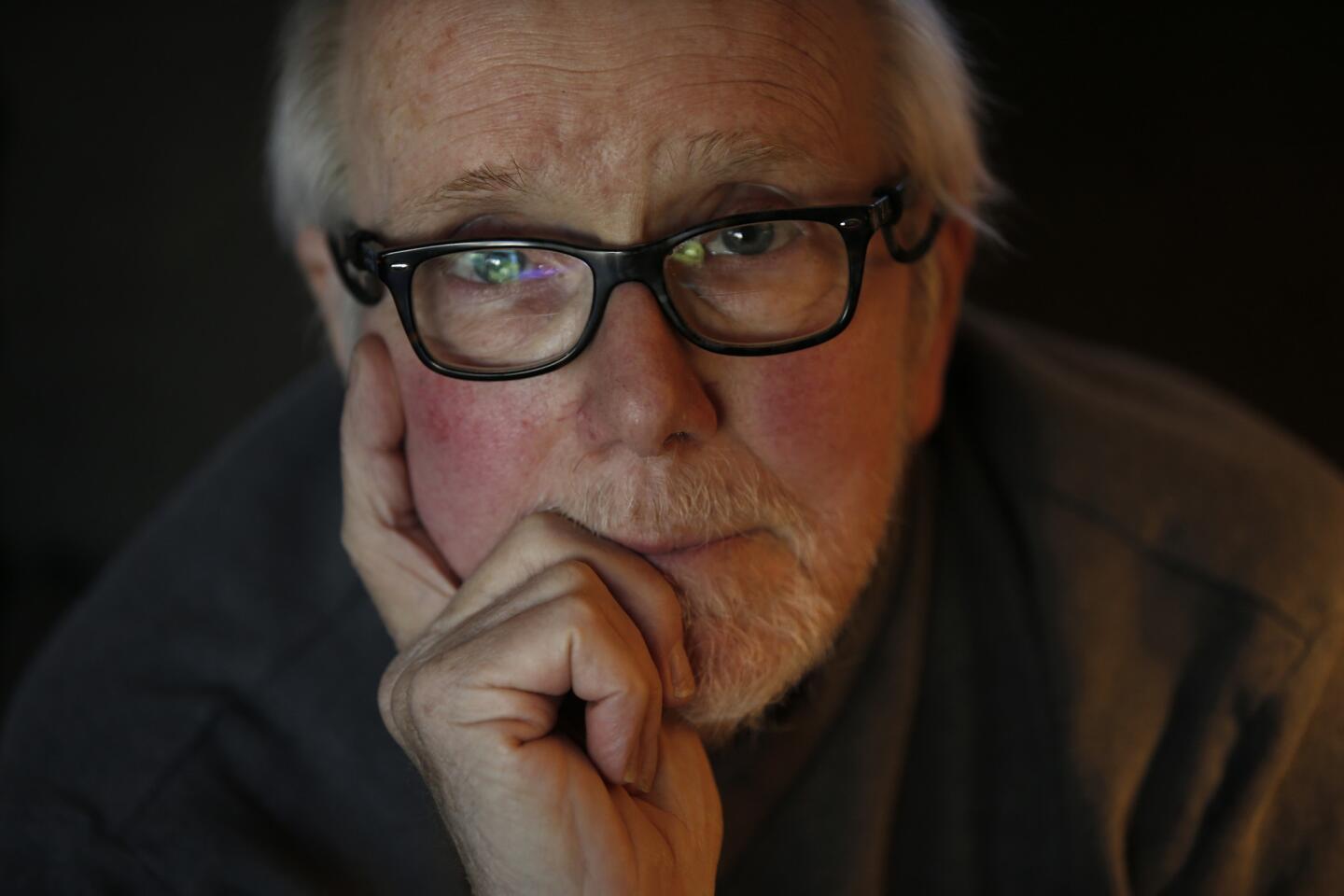

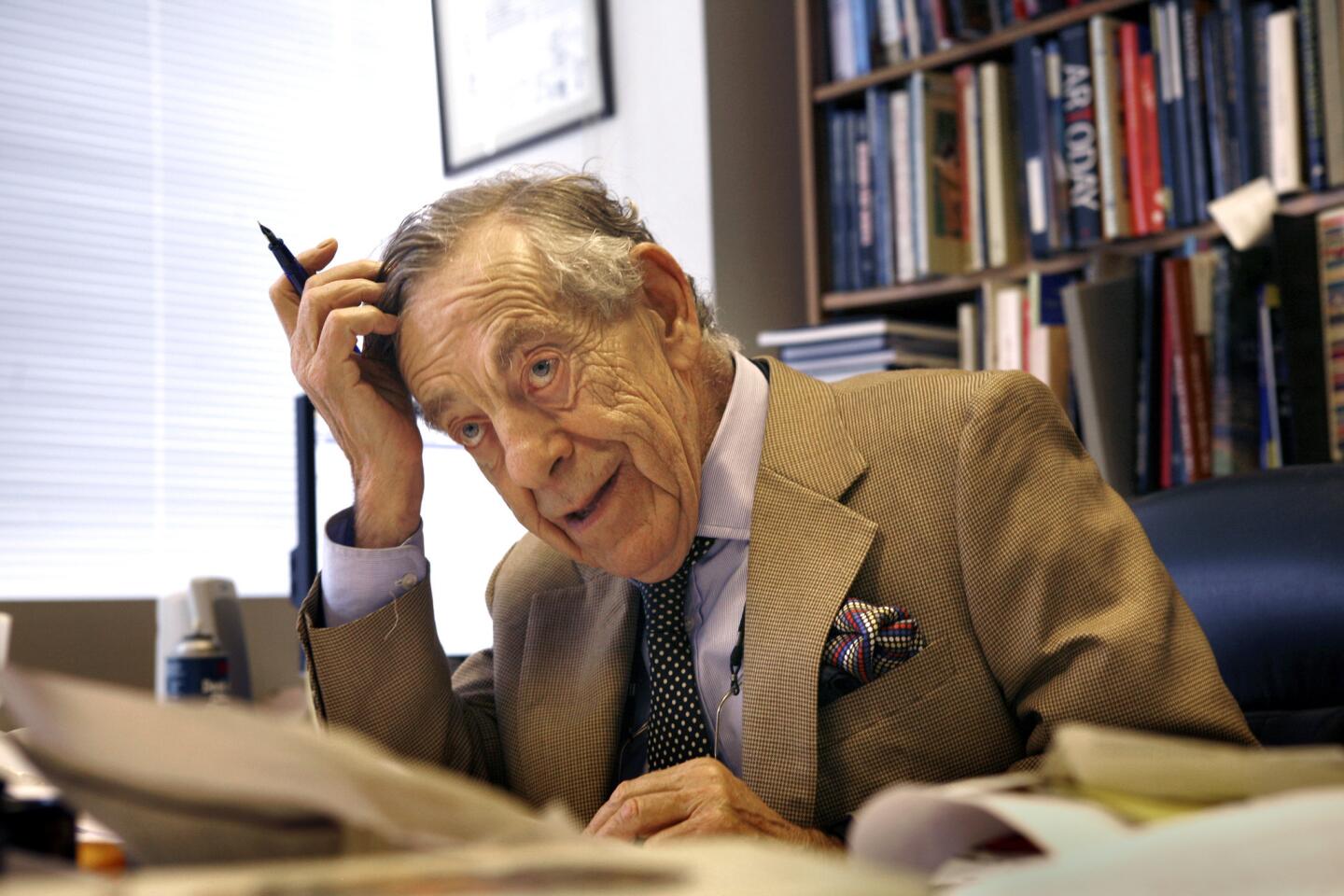

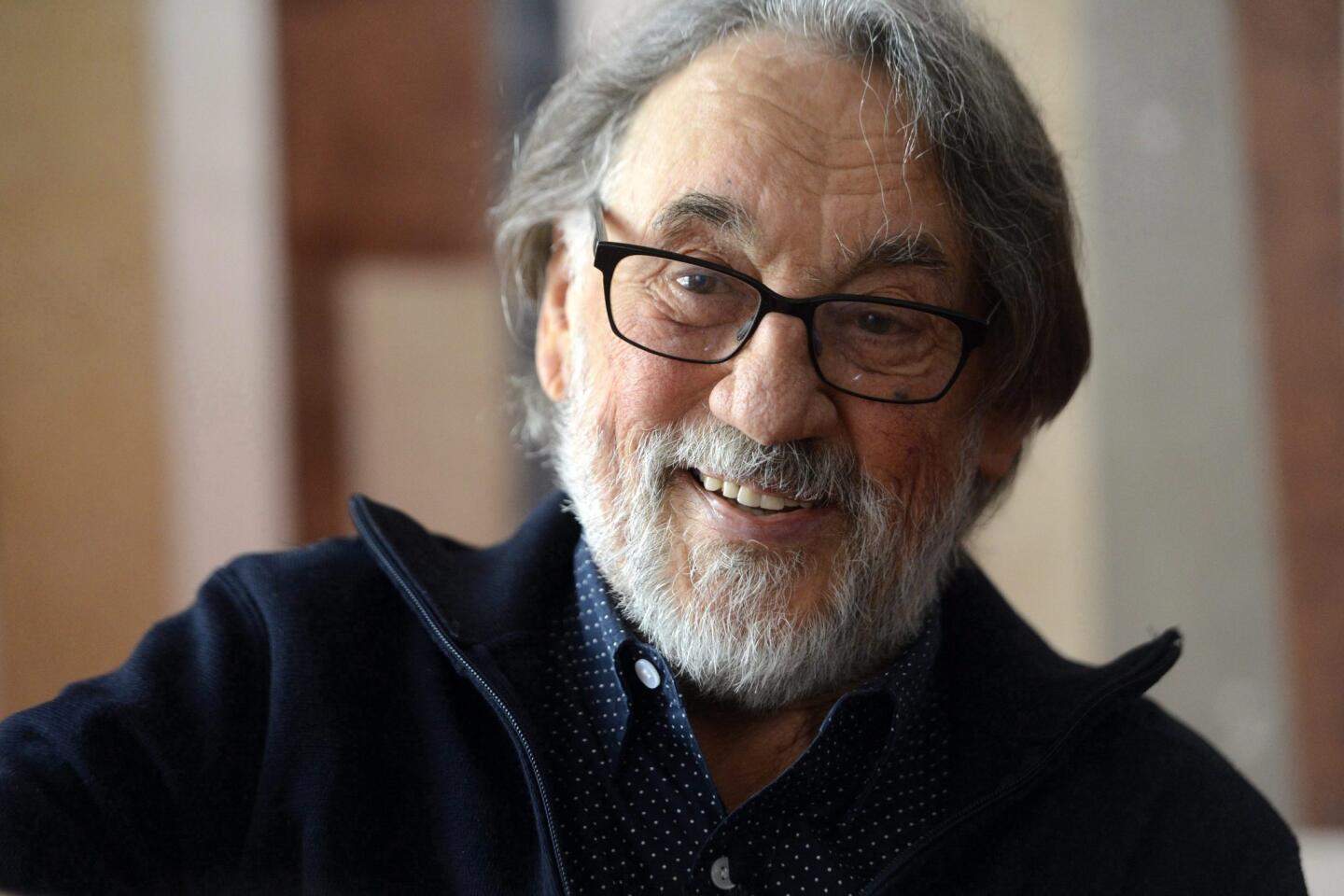

1/5

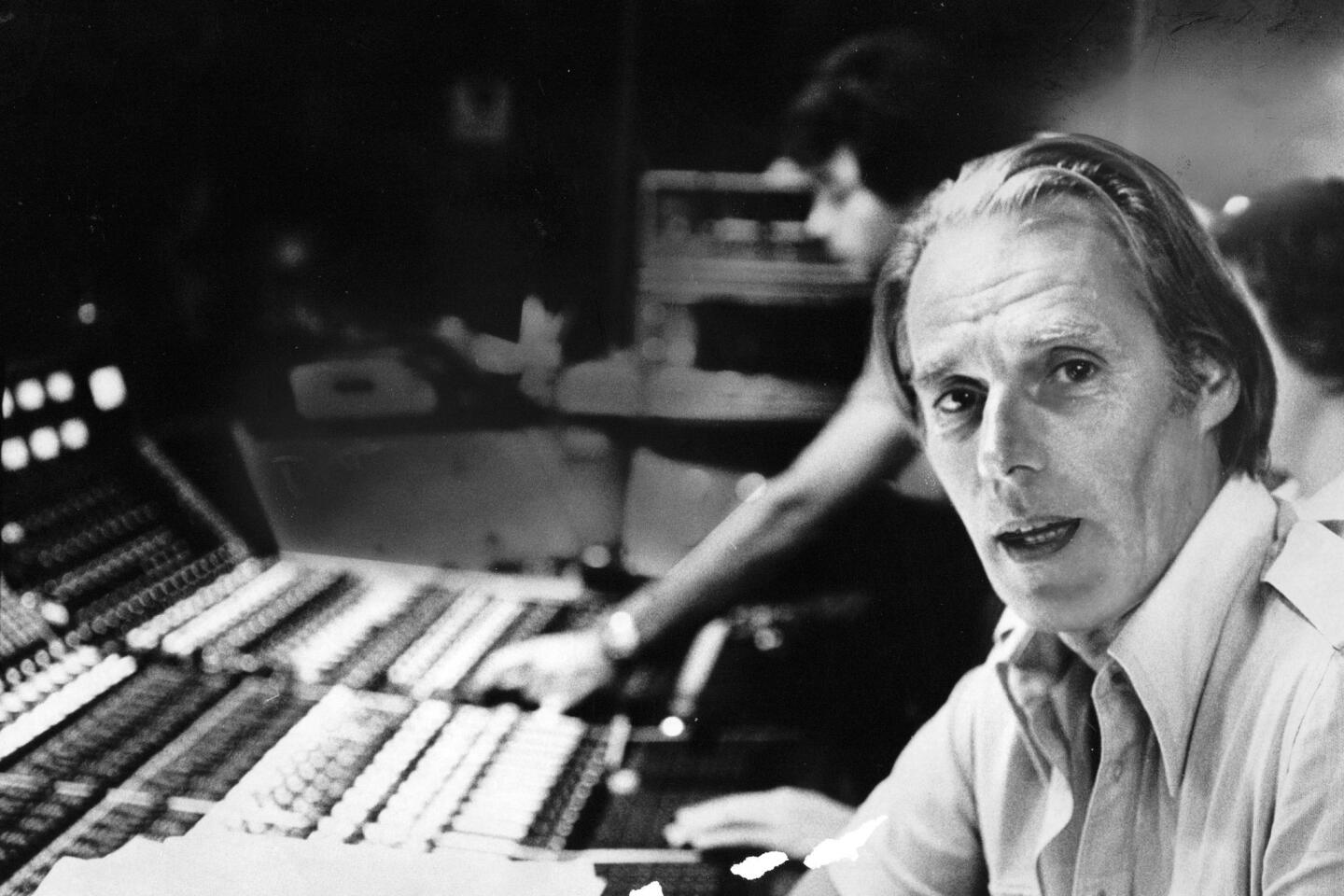

George Martin in 1977. He began working with the Beatles in 1962 after they were signed to Parlophone Records. He would go on to produce most of their recordings until their breakup in 1970.

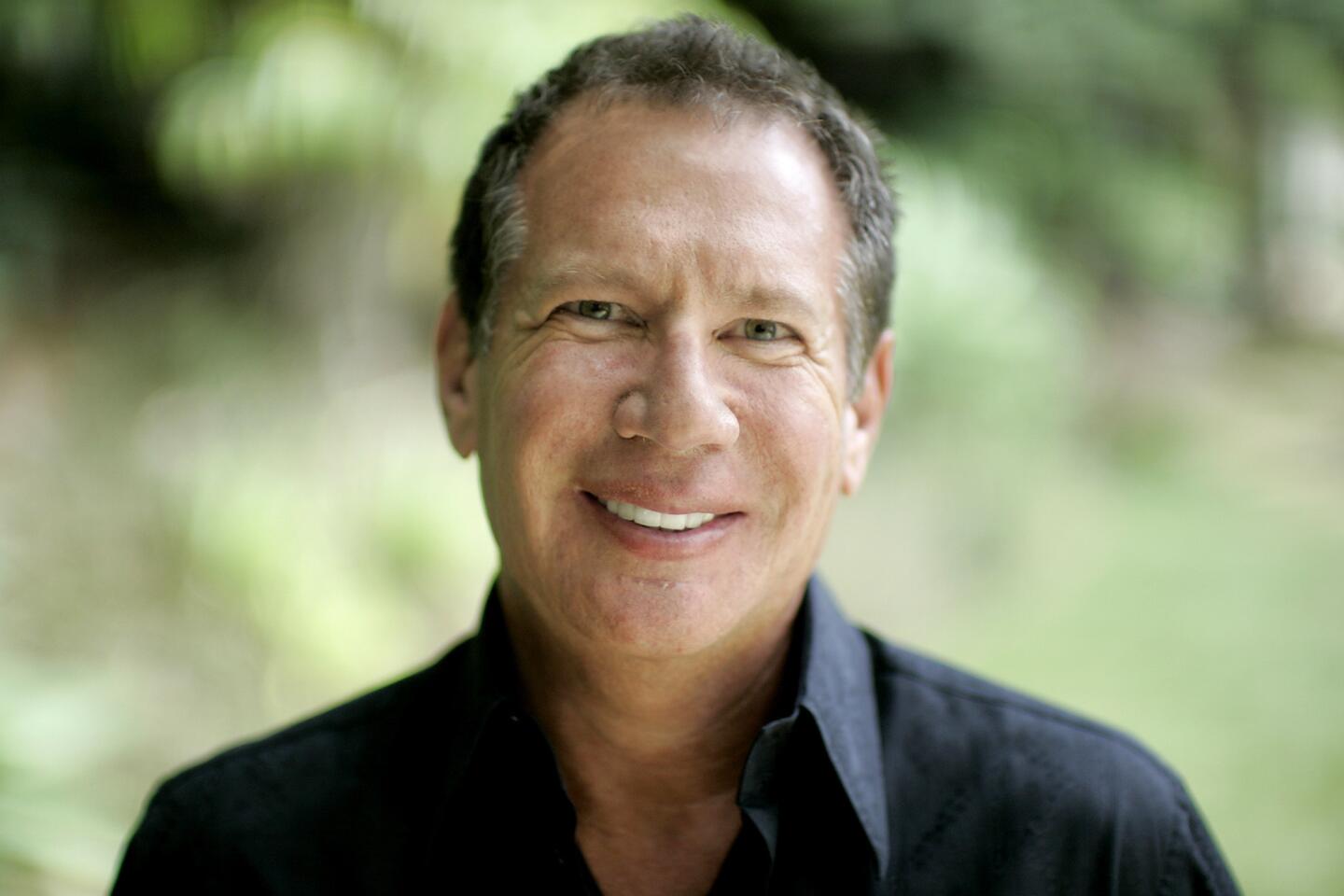

(Tony Barnard / Los Angeles Times) 2/5

George Martin, often called the Fifth Beatle, shortly before he was knighted in June 1996. After that, he was called Sir George.

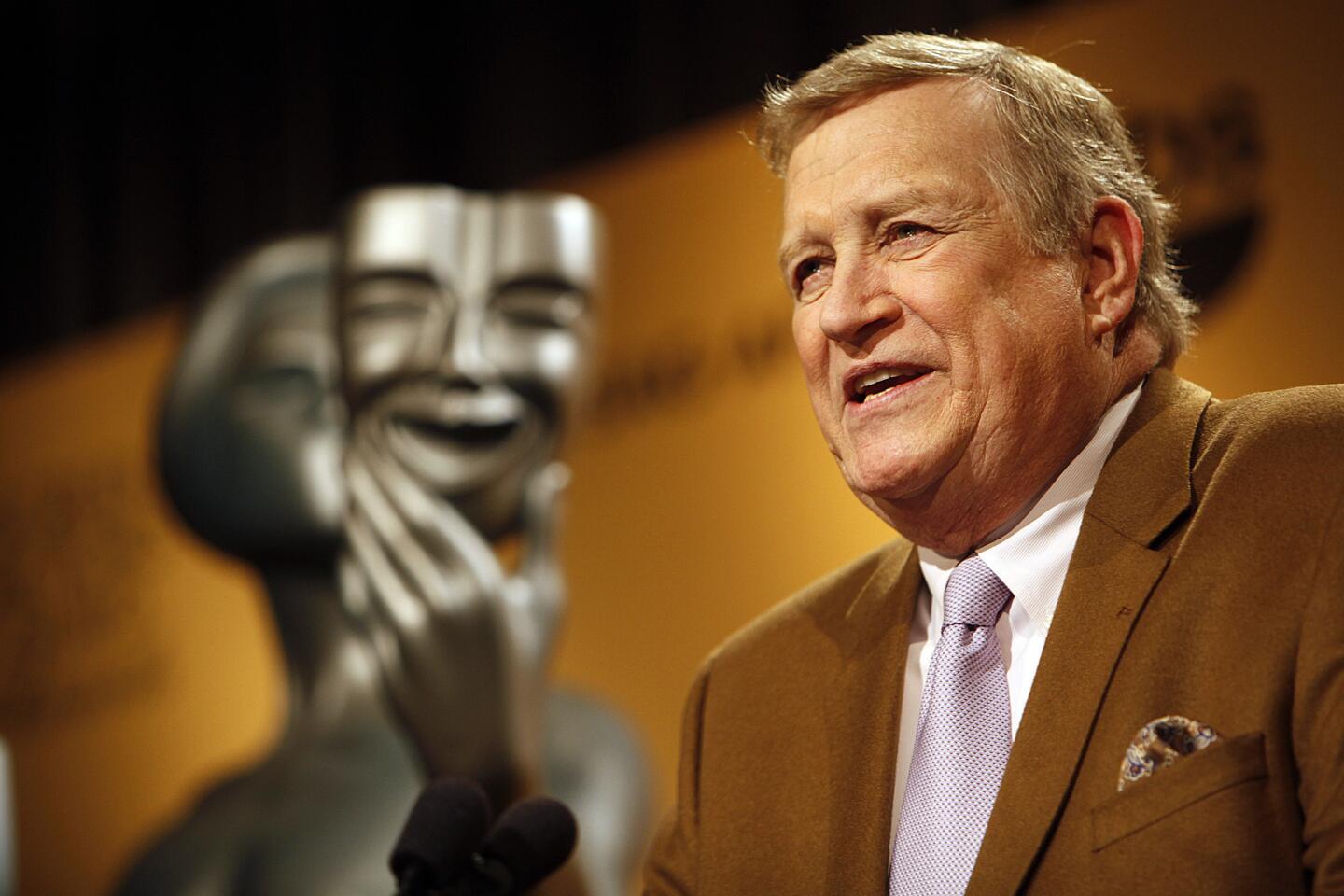

(Barry Batchelor / Associated Press) 3/5

Ringo Starr and George Martin at the 50th Annual Grammy Awards at Staples Center in Los Angeles, Feb. 10, 2008.

(Lawrence K. Ho / Los Angeles Times) 4/5

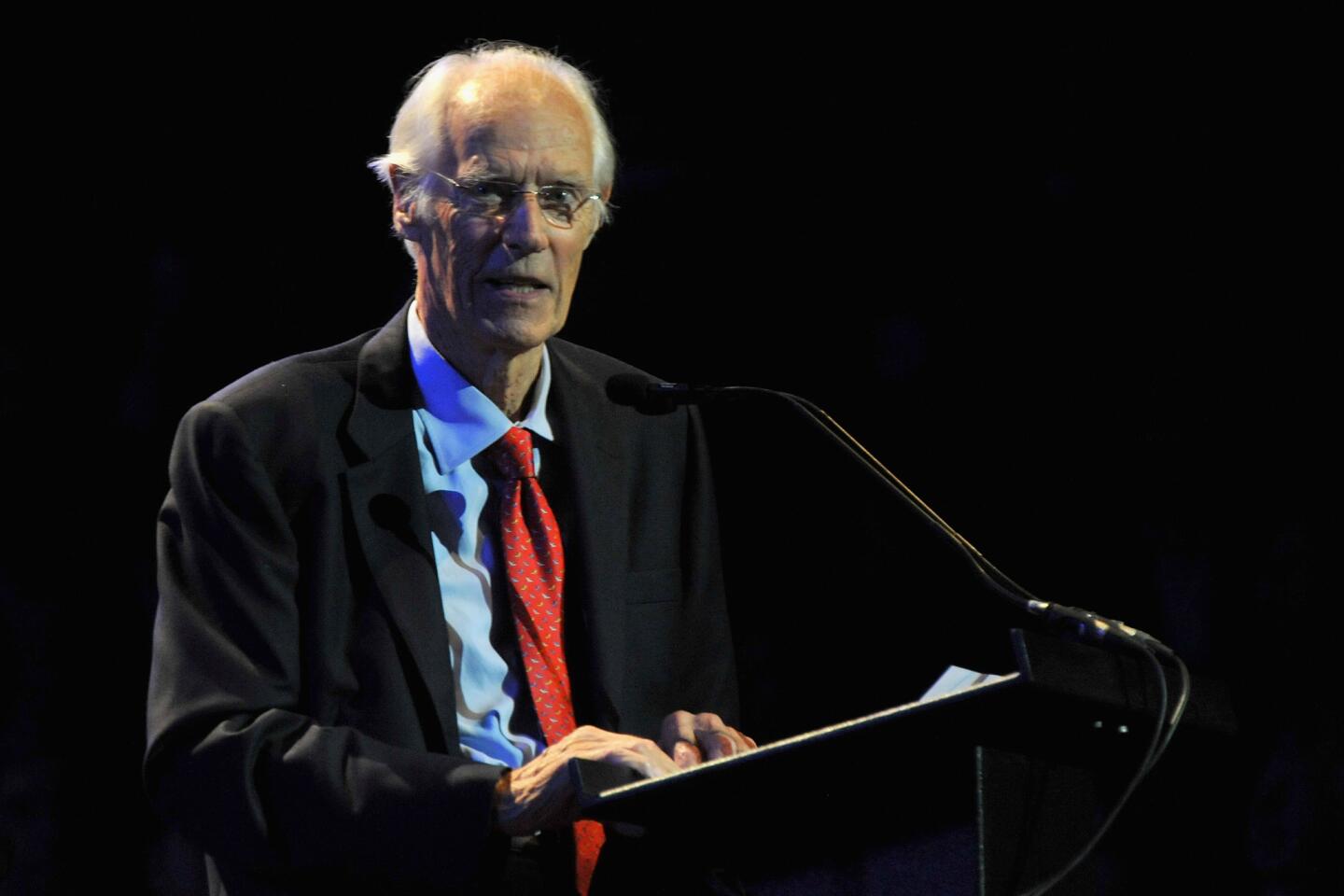

George Martin speaks on stage during the John Barry Memorial Concert at London’s Royal Albert Hall in 2011.

(Jon Furniss / WireImage / Getty Images) 5/5

George Martin and Paul McCartney at “LOVE,” Cirque du Soleil’s celebration of the Beatles in Las Vegas in 2006.

(KMazur / WireImage / Getty Sports) The full range of Martin’s musical skills weren’t tapped during the early years, when the songs and arrangements were relatively simple, but his input was a constant. He suggested, for instance, that they open “Can’t Buy Me Love” with the soaring chorus rather than the more sedate verse.

With the success, Parlophone attracted other British pop acts, several via the Beatles’ manager Epstein, including Cilla Black, Gerry & the Pacemakers and Billy J. Kramer & the Dakotas. Later came the Hollies and Shirley Bassey. In the 52 weeks of 1963, Parlophone singles topped the U.K. chart 37 times.

Martin received an Oscar nomination for musical direction on the Beatles’ 1964 movie “A Hard Day’s Night,” but after a falling-out with director Richard Lester he didn’t work on the follow-up, “Help!,” though he did produce the Beatles’ songs for the 1965 film.

One of those songs was a breakthrough. McCartney’s “Yesterday” was recorded with just the singer and his acoustic guitar, overdubbed with Martin’s string quartet arrangement. It was a radical departure from pop combo form, inaugurating a creative period that would exploit both the traditional and experimental sides of Martin’s talents.

“That was when, as I can see in retrospect, I started to leave my hallmark on the music, when a style started to emerge which was partly of my making,” Martin wrote in “All You Need Is Ears.”

Martin maintained a distance from some aspects of the Beatles’ activities, never joining them in their drug use and remaining skeptical of their quixotic Apple organization. But he was along for their ride into the most psychedelic and iconoclastic territory, shepherding such groundbreaking albums as “Rubber Soul,” “Revolver,” “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band,” “The Beatles” (the so-called “White Album”) and “Abbey Road.”

It was Martin who devised a way to combine two seemingly incompatible segments into the finished “Strawberry Fields Forever,” his favorite Beatles record. He arranged the high-pitched piccolo trumpet to play the fills on “Penny Lane.” For the climax of “A Day in the Life,” he liberated the musicians in the studio orchestra, instructing them to move with sliding effects from low note to high in a loosely organized 24 bars.

Martin continued producing the Beatles even though he had left EMI in 1965 in a dispute over compensation. He and three EMI colleagues established AIR, a producers’ cooperative.

After the Beatles broke up in 1970, Martin worked with acts including America, Jeff Beck, Ella Fitzgerald, Kenny Rogers, the Mahavishnu Orchestra and Cheap Trick. He also produced Elton John’s 1997 Princess Diana tribute single “Candle in the Wind.”

But he never ventured far from the Beatles orbit. He produced three of McCartney’s solo albums, as well as the singer’s theme for the 1973 James Bond movie “Live and Let Die.” He also scored that film, and was musical director for the 1978 film version of “Sgt. Pepper.”

Sometimes he worked simply because of his regard for the legacy. In 1976 he voluntarily went into Capitol Records’ Los Angeles studio to rescue the sound of some early monaural recordings that the label was preparing to reissue in what Martin termed “disastrous” stereo as the “Rock and Roll Music” album.

He selected the tracks for the 1995 and 1996 “Anthology” retrospectives, and conceived and produced the 1998 album “In My Life,” enlisting singers and actors including Jim Carrey, Goldie Hawn and Sean Connery to perform Beatles songs.

He toured with a multimedia presentation on the making of “Sgt. Pepper,” and in 1999 he conducted the Hollywood Bowl Orchestra at its namesake venue (where the Beatles had played more than three decades earlier) in a Beatles program.

Despite progressive hearing loss, he teamed with his producer son Giles to remix the Beatles canon into the score for the Cirque du Soleil’s 2006 stage production “Love.”

Martin won six Grammys and received a lifetime achievement award from the Recording Academy in 1996. He was made a knight bachelor the same year, and in 1999 he was named to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in the non-performer category.

Martin remained immensely proud of his work with the Beatles, especially the progressive nature it was assuming at the end — an end that he felt came too soon.

1/61

Wong’s masterly touch brought a poetic quality to Disney’s “Bambi” that has helped it endure as a classic of animation. The pioneering Chinese American artist influenced later generations of animators. Full obituary

(Peter Brenner / Handout) 2/61

After bursting onto the scene opposite Gene Kelly in the classic 1952 musical “Singin’ in the Rain,” Reynolds became America’s Sweetheart and a potent box office star for years. Her passing came only one day after her daughter, Carrie Fisher, died at the age of 60. Reynolds was 84. Full obituary

(John Rooney / Associated Press) 3/61

George Michael, the English singer-songwriter who shot to stardom in the 1980s as half of the pop duo Wham!, went on to become one of the era’s biggest pop solo artists with hits such as “Faith” and “I Want Your Sex.” He was 53. Full obituary

(Francois Mori / Associated Press) 4/61

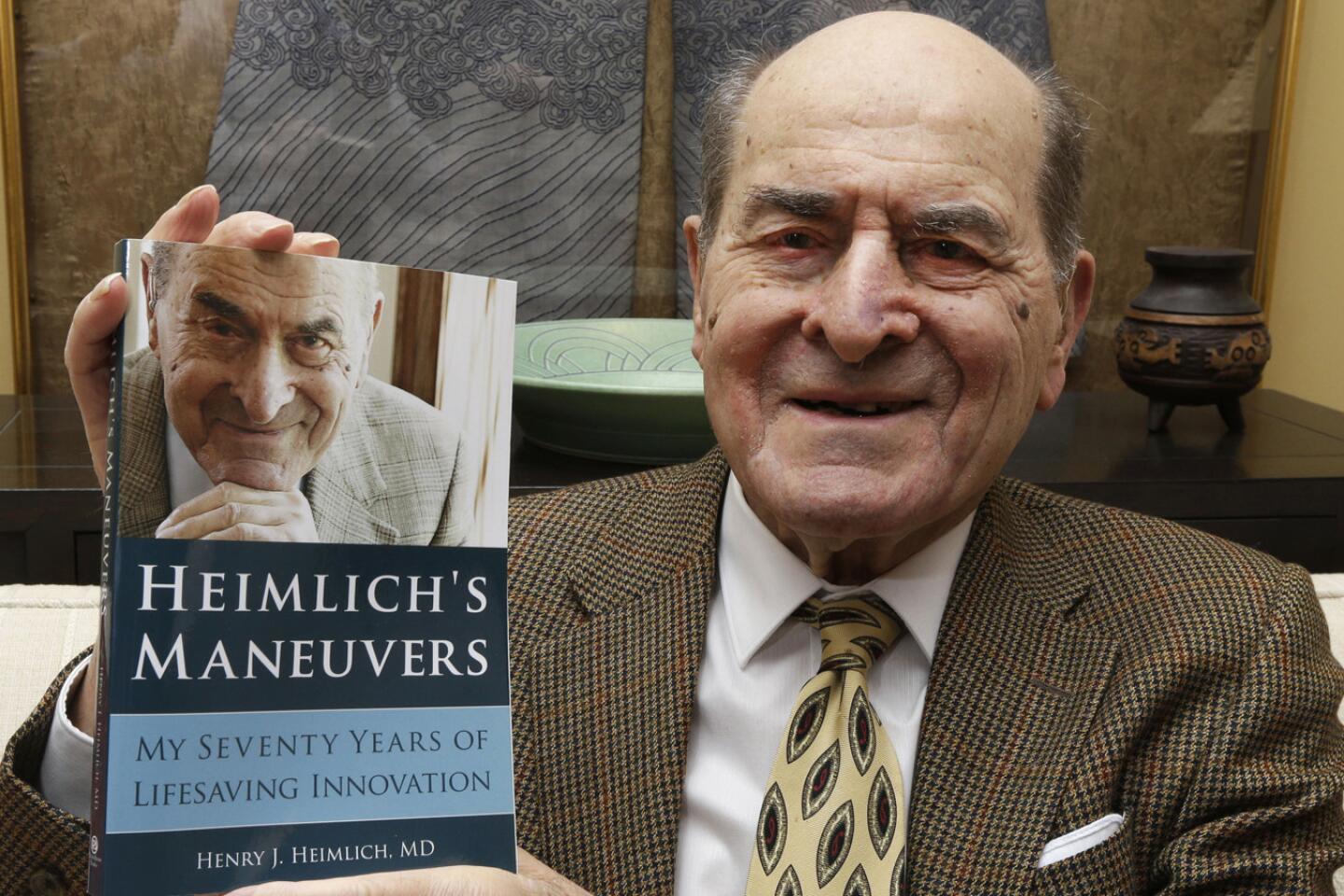

The thoracic surgeon came up with an anti-choking technique in 1974. So simple it could be performed by children, the eponymous maneuver made Heimlich a household name. He was 96. Full obituary

(Al Behrman / Associated Press) 5/61

The hugely popular south Indian actress later turned to politics and became the highest elected official in the state of Tamil Nadu. She was 68. Full obituary

(AFP / Getty Images) 6/61

Best known for her portrayal of Carol Brady on “The Brady Bunch,” Henderson

portrayed an idealized mother figure for an entire generation. Her character was the center of the show, cheerfully mothering her brood in an era when divorce was becoming more common. She was 82. Full obituary

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 7/61

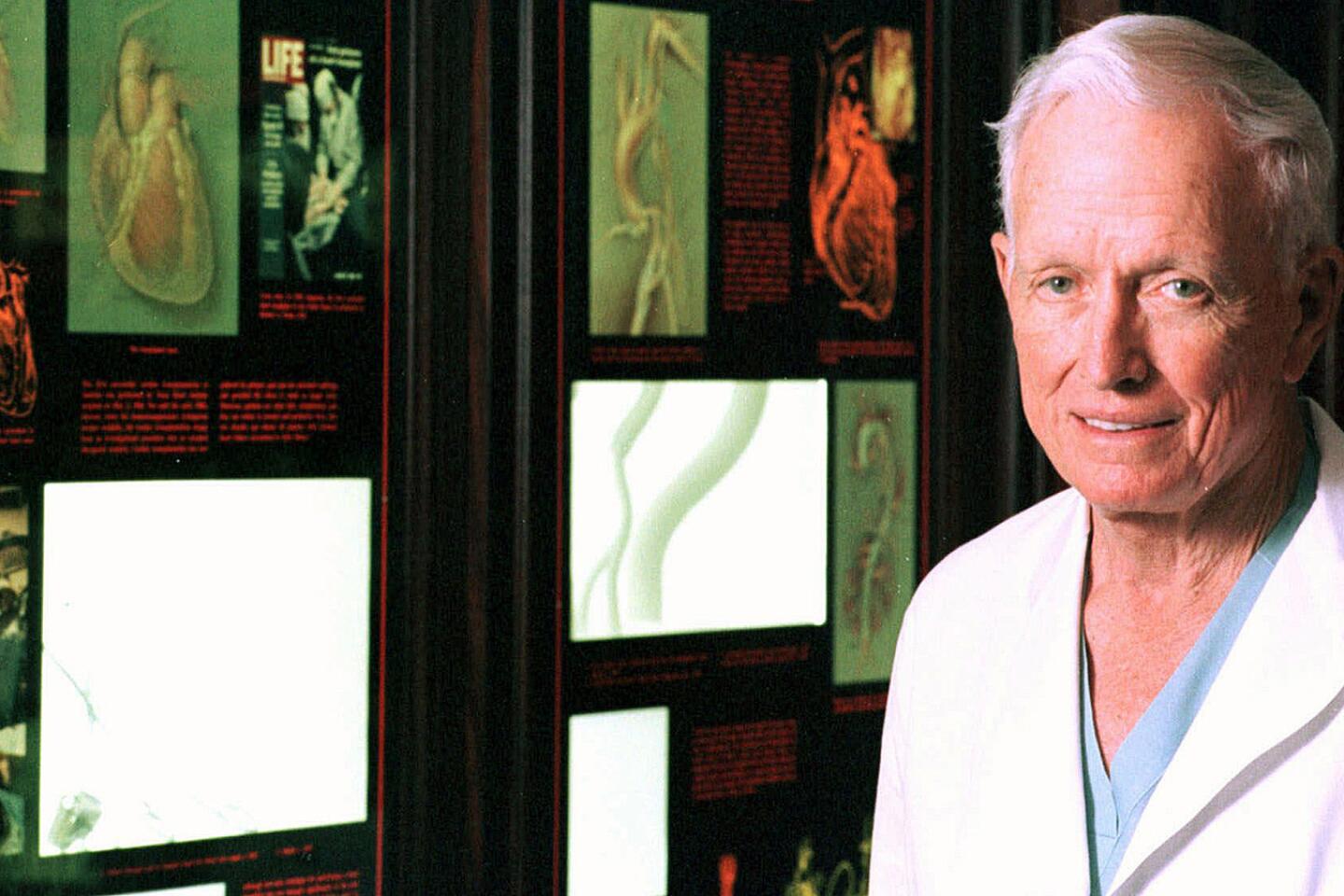

Dubbed “Dr. Wonderful” by the media, the Texas surgeon performed the first successful heart transplant in the United States and the world’s first implantation of a wholly artificial heart. He also founded the Texas Heart Institute in Houston. He was 96. Full obituary

(David J. Phillip / Associated Press) 8/61

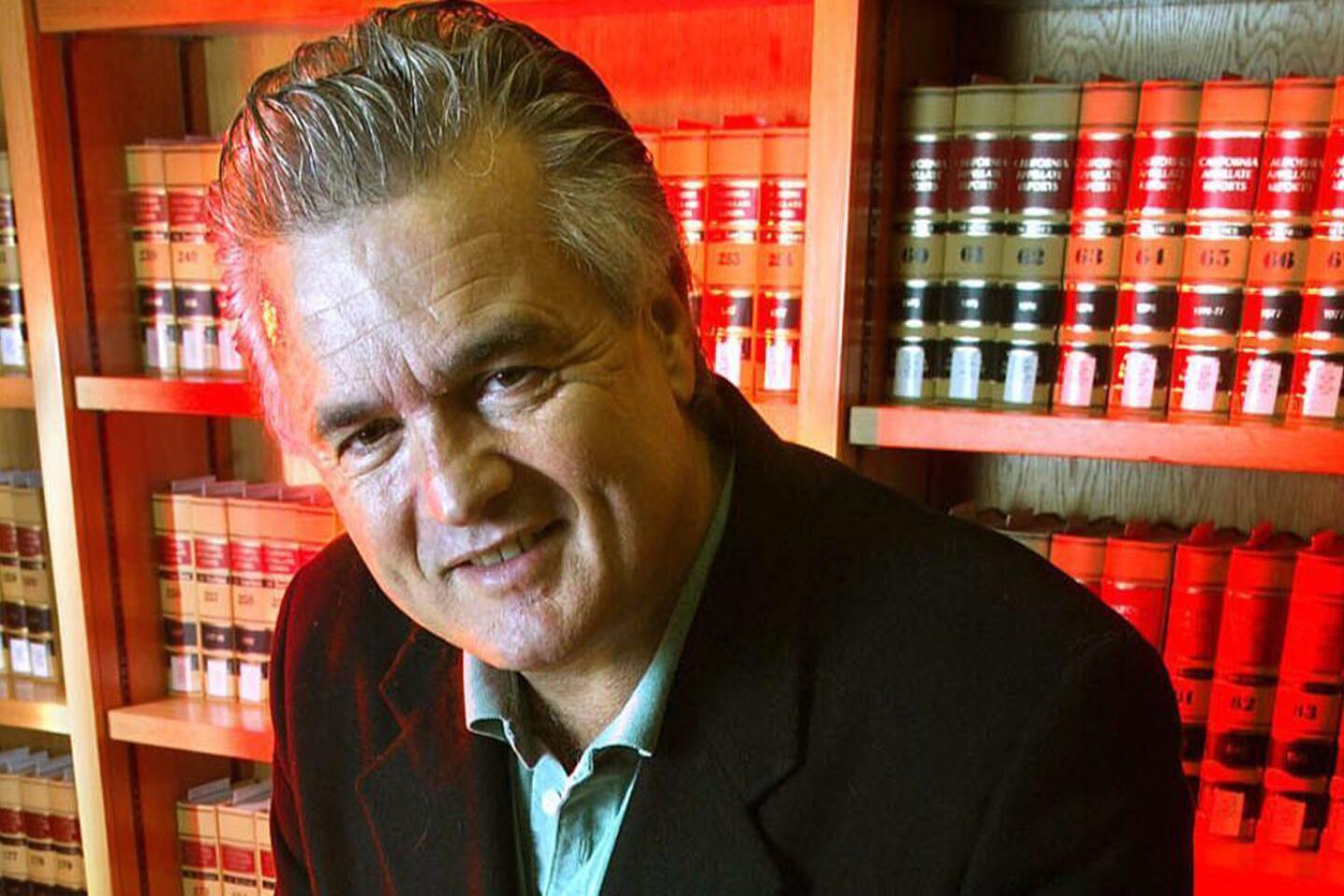

The prominent Los Angeles attorney went from defending his father, a powerful mob boss, to representing celebrities, corrupt businessmen, drug kingpins and the so-called Hollywood Madam, Heidi Fleiss. He was 70. Full obituary

(Ken Hively / Los Angeles Times) 9/61

The award-winning journalist wrote for the Washington Post and the New York Times before becoming an anchor of public television news programs “PBS NewsHour” and “Washington Week.” Her career also included moderating the vice presidential debates in 2004 and 2008. She was 61. Full obituary

(Brendan Smialowski / Getty Images) 10/61

Instantly recognizable for his long white mane and a rich, hearty voice, Russell sang, wrote and produced some of rock ‘n’ roll’s top records. His hits included “Delta Lady,” “Roll Away the Stone,” “A Song for You” and “Superstar.” He was 74. Full obituary

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times) 11/61

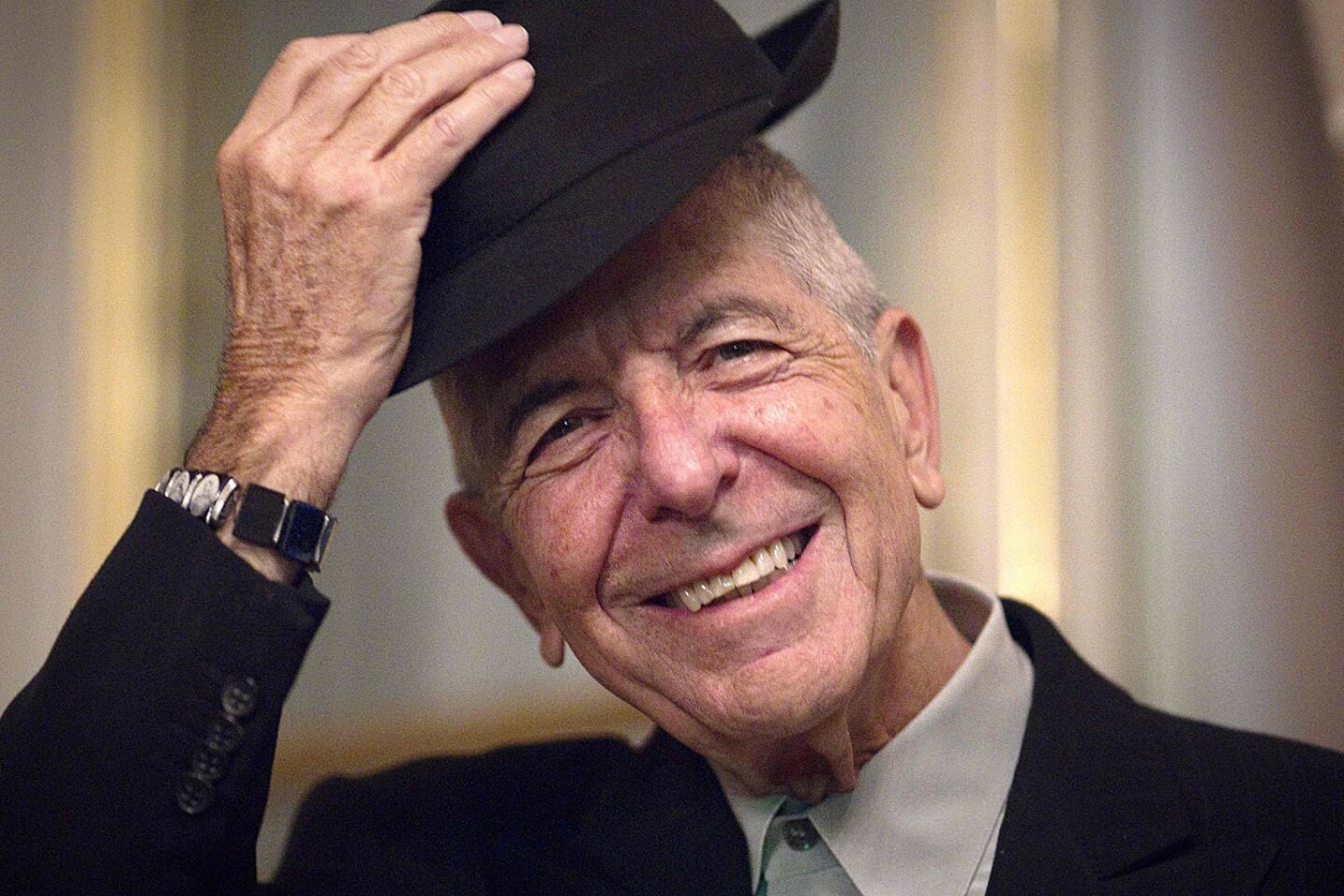

The singer-songwriter’s literary sensibility and elegant dissections of desire made him one of popular music’s most influential and admired figures for four decades. Cohen is best known for his songs such as “Hallelujah,” “Suzanne” and “Bird on the Wire.” He was 82. Full obituary

(Joel Saget / AFP / Getty Images) 12/61

Reno was the first woman to serve as United States attorney general. Her unusually long tenure began with a disastrous assault on cultists in Texas and ended after the dramatic raid that returned Elian Gonzalez to his Cuban father. She was 78. Full obituary

(Dennis Cook / Associated Press) 13/61

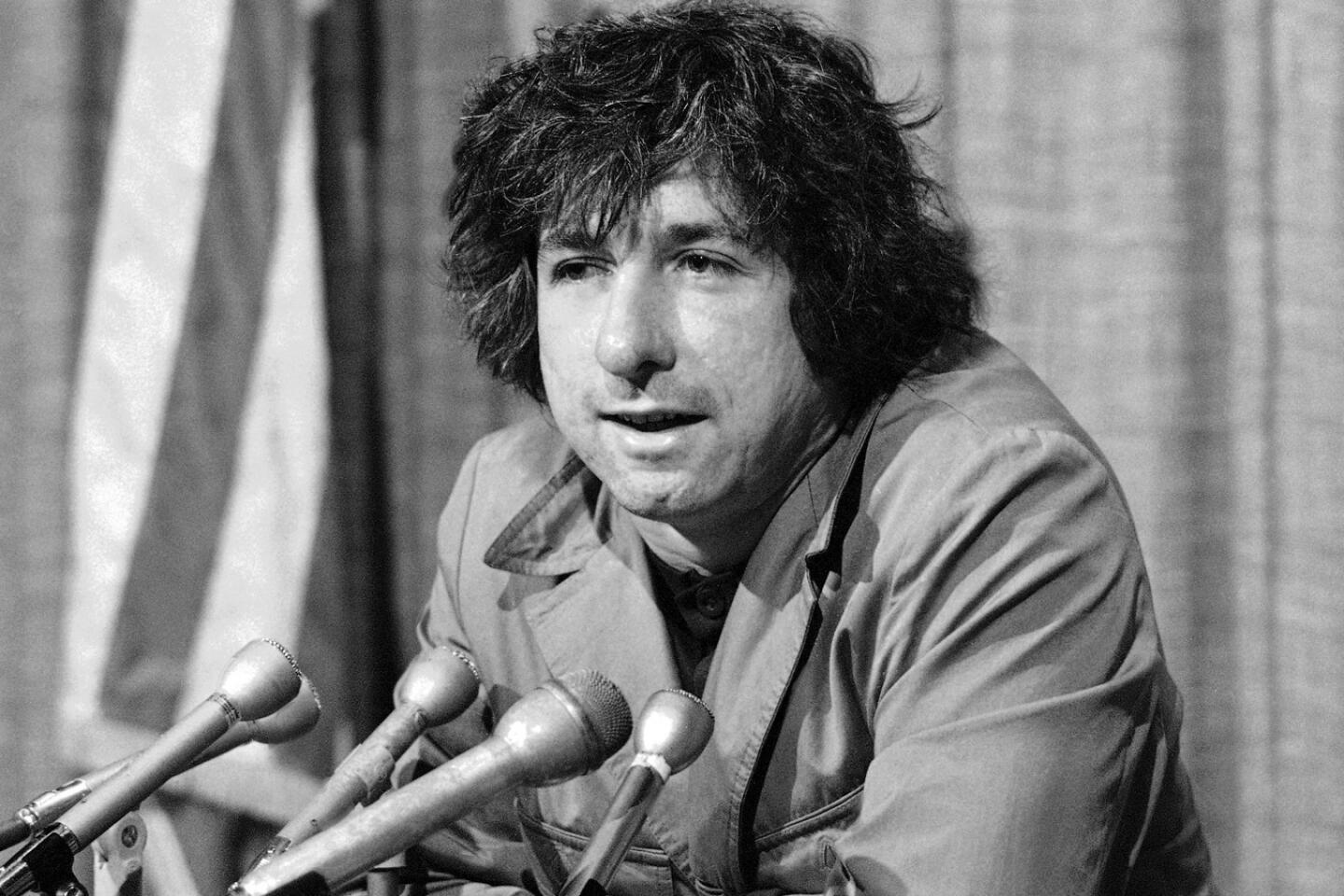

The 1960s radical was in the vanguard of the movement to stop the Vietnam War and became one of the nation’s best-known champions of liberal causes. He was 76. Full obituary

(George Brich / Associated Press) 14/61

Tabei was the first woman to climb Mount Everest in 1975. In 1992, she also became the first woman to complete the “Seven Summits,” reaching the highest peaks of the seven continents. She was 77. Full obituary

(AFP / Getty Images) 15/61

Nixon was the creative force behind the popular soap operas “One Life to Live” and “All My Children.” She was a pioneer in bringing serious social issues, like racism, AIDS and prostitution, to daytime television. She was 93. Full obituary

(Chris Pizzello / Associated Press) 16/61

The former Israeli president was one of the founding fathers of Israel. The Nobel peace prize laureate was an early advocate of the idea that Israel’s survival depended on territorial compromise with the Palestinians. He was 93. Full obituary

(AFP / Getty Images) 17/61

A seven-time professional major tournament champion, Palmer revolutionized sports marketing as it is known today, and his success contributed to increased incomes for athletes across the sporting spectrum. He was 87. Full obituary

(David J. Phillip / Associated Press) 18/61

Known as the Vatican’s exorcist, Amorth, a Roman Catholic priest, helped promote the ritual of banishing the devil from people or places. He was 91. Full obituary

(AFP / Getty Images) 19/61

The American playwright was known for works such as “The Zoo Story,” “The Sandbox,” “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” and “A Delicate Balance.” He was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for drama three times. He was 88. Full obituary

(Jennifer S. Altman / For the Times) 20/61

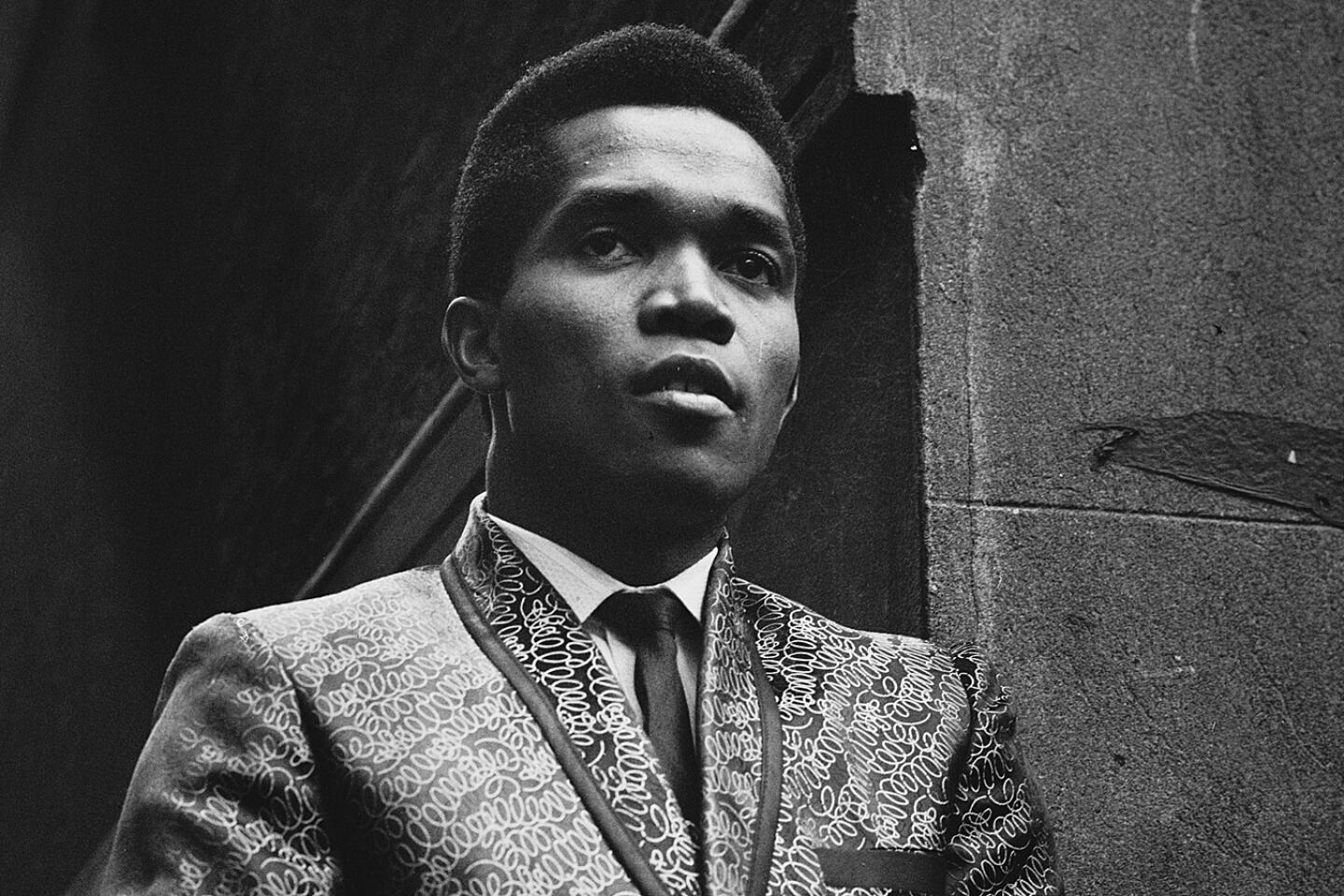

The ska pioneer and Jamaican music legend recorded thousands of records, including such hits as “Al Capone” and “Judge Dread.” He helped ignite the ska movement in England, and later helped carry it into the rock-steady era in the mid-1960s. He was 78. Full obituary

(Larry Ellis / Getty Images) 21/61

Known as “the first lady of anti-feminism,” Schlafly was a political activist who galvanized grass-roots conservatives to help defeat the Equal Rights Amendment and, in ensuing decades, effectively push the Republican Party to the right. She was 92. Full obituary

(Christine Cotter / Los Angeles Times) 22/61

O’Brian helped tame the Wild West as the star of TV’s “The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp” and was the founder of a long-running youth leadership development organization. “Wyatt Earp” became a top 10-rated series and made O’Brian a household name. He was 91. Full obituary

(Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times) 23/61

Jerry Heller, the early manager of N.W.A, was an important and colorful personality in the emerging West Coast rap scene in the 1980s. Heller was 75. Full obituary

(Lori Shepler / Los Angeles Times) 24/61

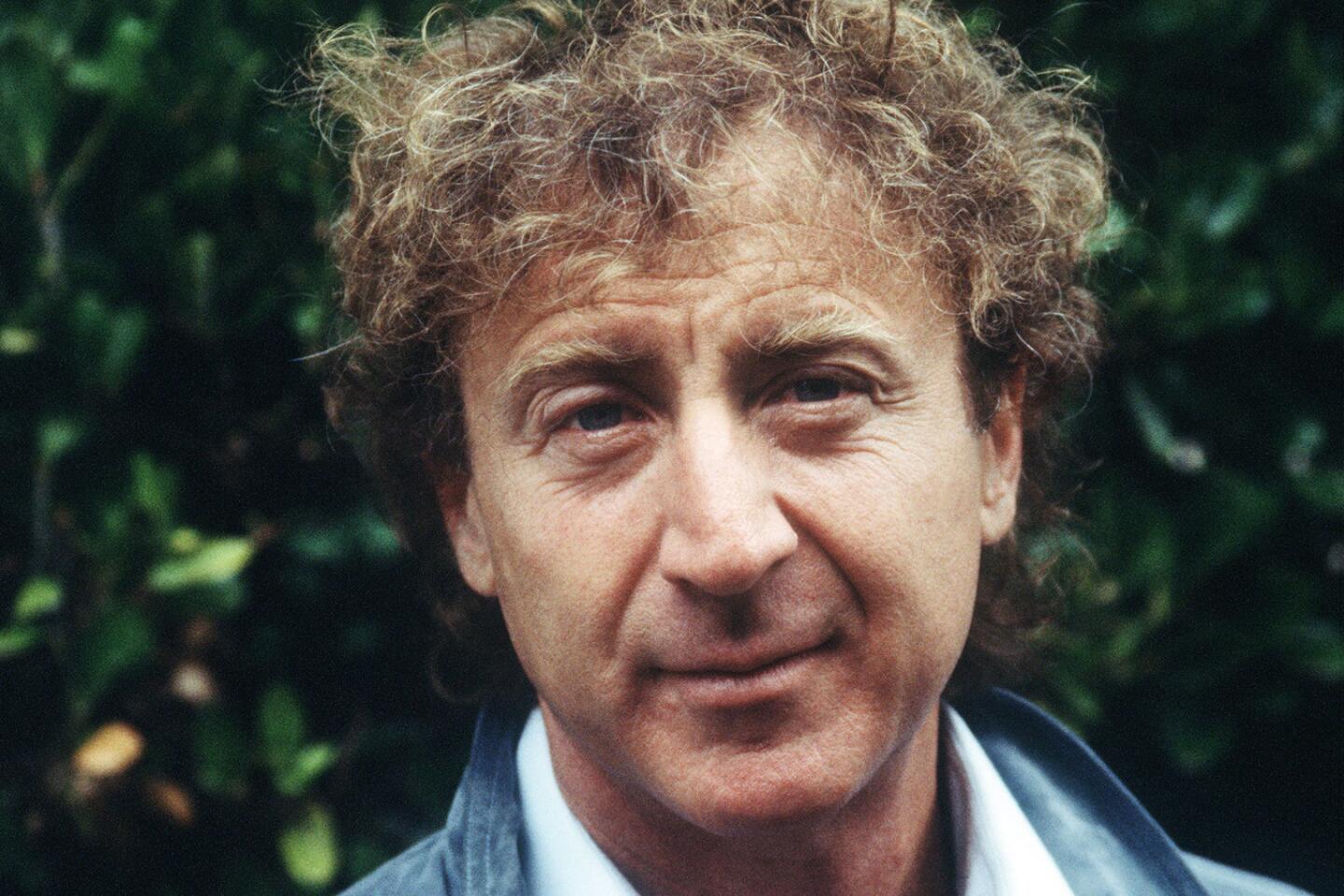

Two-time Oscar nominee Gene Wilder brought a unique blend of manic energy and world-weary melancholy to films as varied as 1971’s children’s movie “Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory” and the 1980 comedy “Stir Crazy.” He was 83. Full obituary

(AFP / Getty Images) 25/61

The beloved top-selling Mexican singer wooed crowds on both sides of the border with ballads of love and heartbreak for more than four decades. He was 66. Full obituary

(Wilfredo Lee / Associated Press) 26/61

Known as the “queen of knitwear,” Sonia Rykiel became a fixture of Paris’ fashion scene, starting in 1968. French President Francois Hollande praised her as “a pioneer” who “offered women freedom of movement.” She was 86. Full obituary

(Thibault Camus / Associated Press) 27/61

The conservative political commentator hosted the long-running weekly public television show “The McLaughlin Group” that helped alter the shape of political discourse since its debut in 1982. He was 89. Full obituary

(Kevin Wolf / Associated Press) 28/61

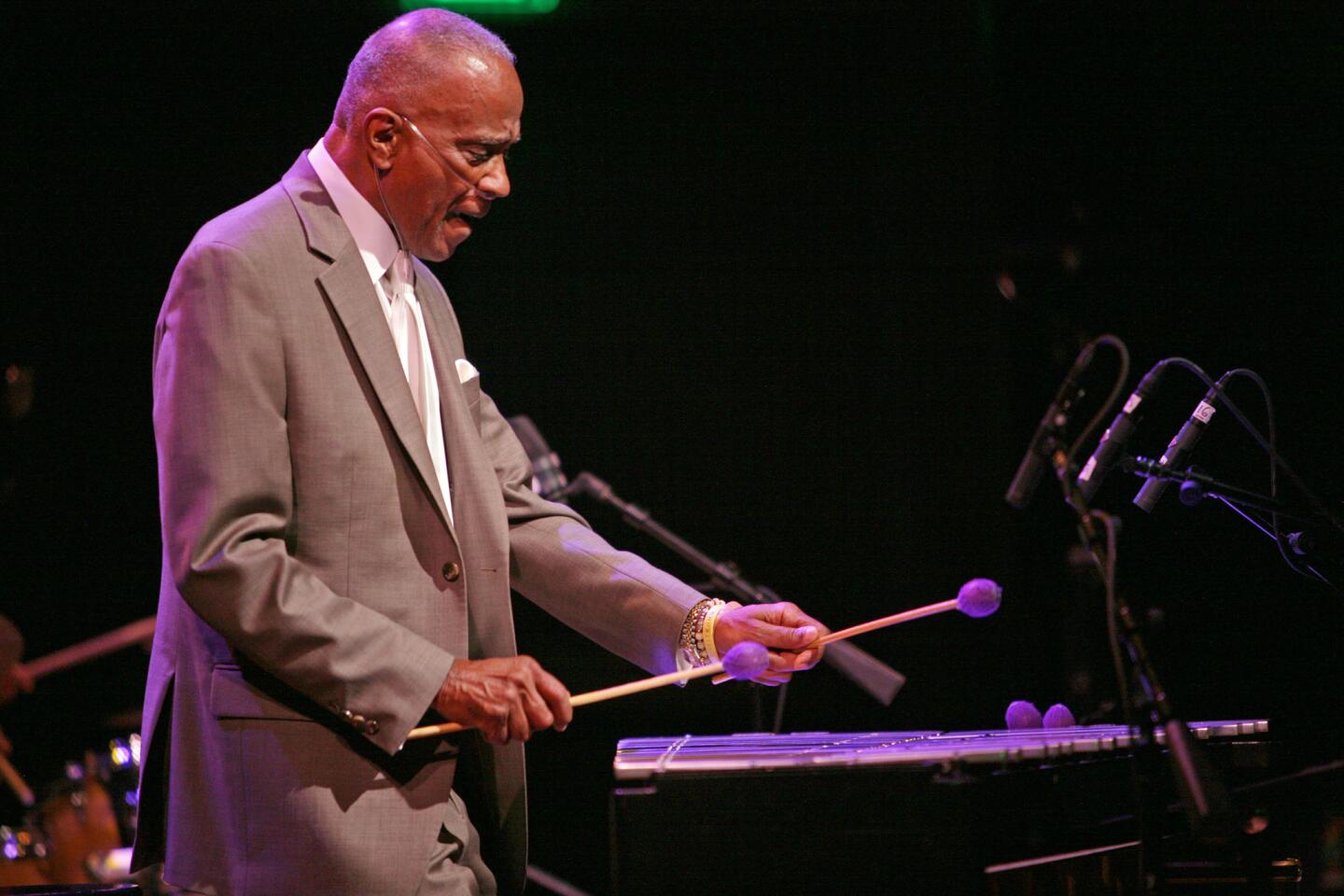

Best-known for his post-bop recordings for Blue Note Records in the 1960s and 1970s, the inventive jazz vibraphonist played with a litany of jazz greats as both bandleader and sideman during a career spanning more than 50 years. He was 75. Full obituary

(Scott Chernis / Associated Press) 29/61

The British actor, who was 3-foot-8, gave life to the “Star Wars” droid R2-D2, one of the most beloved characters in the space-opera franchise and among the most iconic robots in pop culture history. He was 81. Full obituary

(Reed Saxon / Associated Press) 30/61

For many in L.A., Folsom was the face of the Parent Teacher Student Assn., better known as the PTSA or PTA. He served as the official and unofficial watchdog over the Los Angeles Unified School District and wrote about his experiences in his blog. He was 69. Full obituary

(Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times) 31/61

Fountain combined the Swing Era sensibility of jazz clarinetist Benny Goodman with the down-home, freewheeling style characteristic of traditional New Orleans jazz to become a national star in the 1950s as a featured soloist on the “The Lawrence Welk Show.” He was 86. Full obituary

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times) 32/61

Lowery was a pioneer in efforts to help people suffering from poverty, addiction and mental illness move out of tents and cardboard boxes on Los Angeles’ sidewalks and into supportive housing. She was 70. Full obituary

(Lawrence K. Ho / Los Angeles Times) 33/61

Nixon, a Hollywood voice double, can be heard in place of the leading actresses in such classic movie musicals as “West Side Story,” “The King and I” and “My Fair Lady.” She was 86. Full obituary

(Rob Kim / AFP/Getty Images) 34/61

The department store heir’s widow was a socialite and philanthropist who hobnobbed with the world’s elite, epitomized high fashion and was best friends with former first lady Nancy Reagan. She was 93. Full obituary

(Evan Agostini / Associated Press) 35/61

The author and teacher was long established as a leading literary figure of Southern California. Her works include “Golden Days,” “There Will Never Be Another You” and her memoir “Dreaming, Hard Luck and Good Times in America.” She was 82. Full obituary

(Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times) 36/61

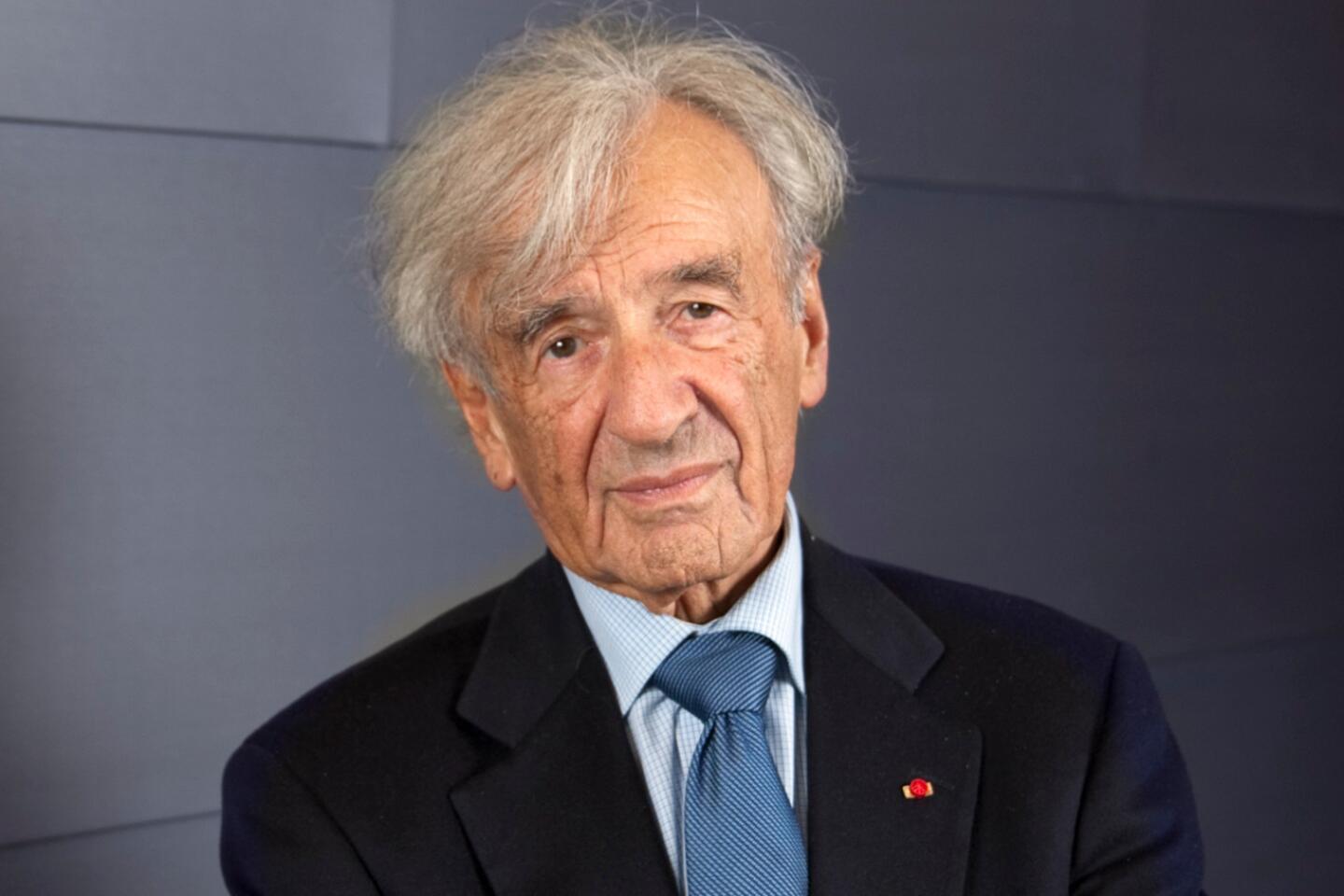

The Nazi concentration camp survivor won the Nobel in 1986 for his message “of peace, atonement and human dignity.” “Night,” his account of his year in death camps, is regarded as one of the most powerful achievements in Holocaust literature. He was 87. Full obituary

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 37/61

One of the greatest basketball coaches of any gender or generation, Summitt spent 38 years as coach of the University of Tennessee women’s basketball team before dementia forced her early retirement. She was 64. Full obituary

(Wade Payne / Associated Press) 38/61

The iconic New York Times fashion photographer darted around New York on a humble bicycle to cover the style of high society grand dames and downtown punks with equal verve. He was 87. Full obituary

(Mark Lennihan / Associated Press) 39/61

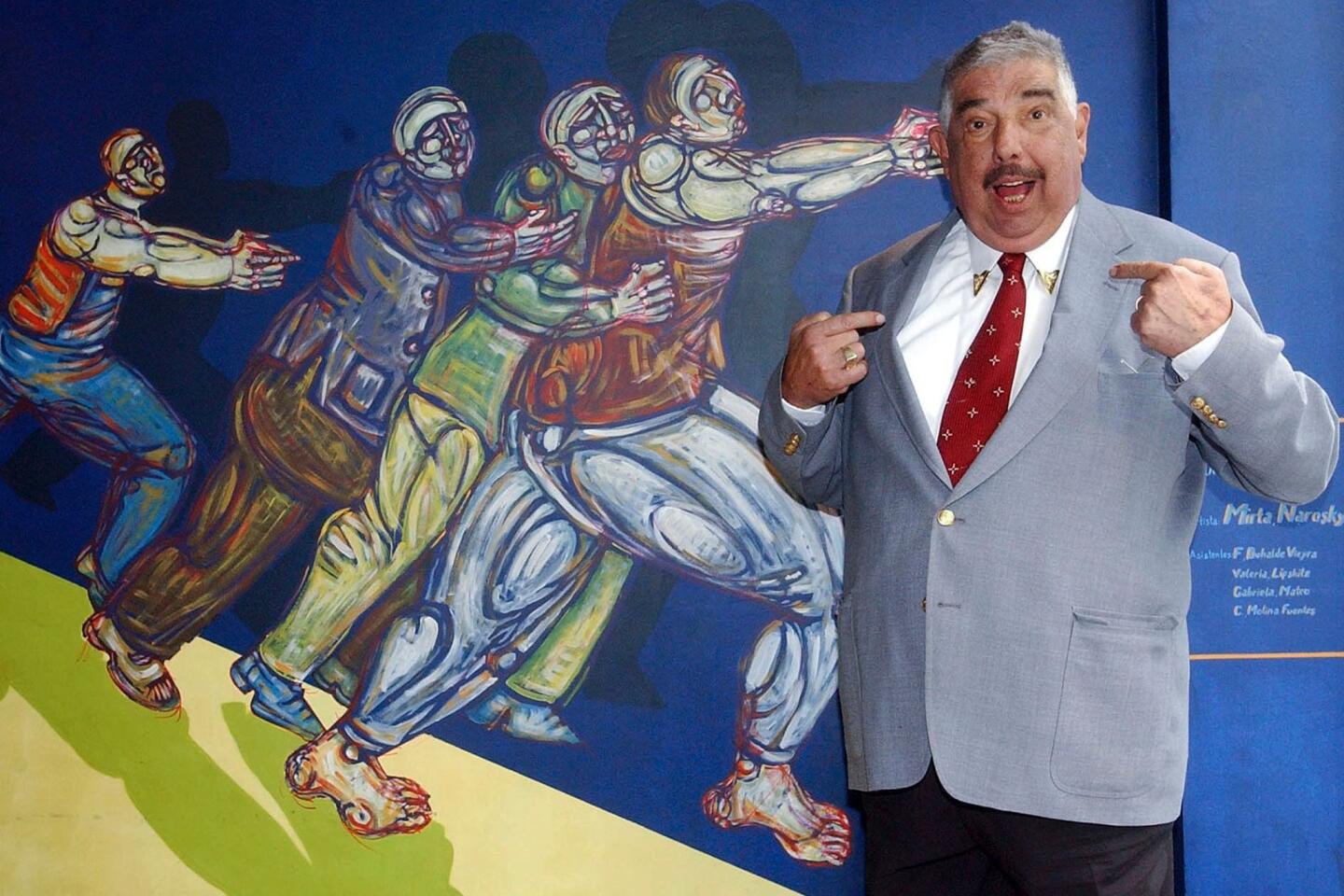

Aguirre was best known for his portrayal of the towering “Profesor Jirafales,” the likable and often disrespected giraffe teacher on the 1970s-era hit show “El Chavo del Ocho.” The screwball comedy helped usher in an era of edgier comedy in Mexico and elsewhere. Aguirre was 82. Full obituary

(AFP / Getty Images) 40/61

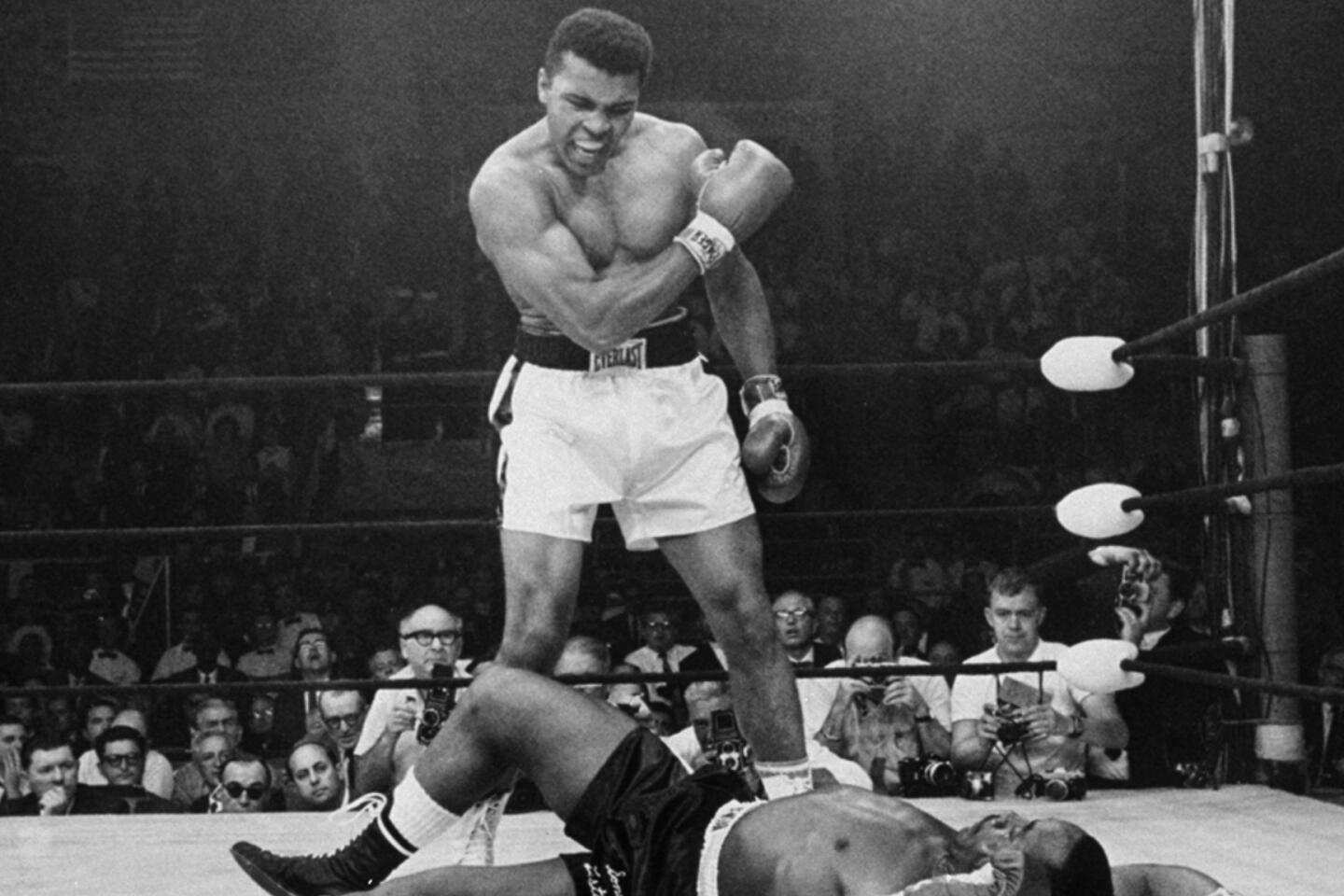

The three-time heavyweight boxing champion’s brilliance in the ring and bravado outside it made his face one of the most recognizable in the world. He was 74. Full obituary

(John Rooney / Associated Press) 41/61

Like Walter Cronkite and Edward R. Murrow, the CBS newsman became part of a group of journalists who set the tone for storytelling on television. He was on “60 Minutes” for 46 years, holding the longest tenure on prime-time television of anyone in history. He was 84. Full obituary

(Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times) 42/61

The first African American chief of the Los Angeles Police Department, Williams steadied the agency in the tumultuous wake of the 1992 riots but was distrusted as an outsider by many officers and politicians. He was 72. Full obituary

(Nick Ut / Associated Press) 43/61

Best known for her role as Marie Barone on “Everybody Loves Raymond,” Roberts won four Emmys for her work on that show and one for her work on “St. Elsewhere.” She was 90. Full obituary

(Ken Hively / Los Angeles Times) 44/61

The country music legend sang of his law-breaking Bakersfield youth and penned a stream of No. 1 hits. He owed some of his fame to conservative anthems, including the combative 1969 release “Okie from Muskogee,” which seemed to mock San Francisco’s anti-war hippies. He was 79. Full obituary

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times) 45/61

The acclaimed Native American historian was the last surviving war chief of Montana’s Crow Tribe. President Obama awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2009. He was 102. Full obituary

(J. Scott Applewhite / Associated Press) 46/61

Germany’s longest-serving foreign minister brokered an end to the painful 40-year division of his homeland in 1990, but only after persevering for decades through the most tragic and destructive phases of Germany’s 20th century history. He was 89. Full obituary

(Martin Meissner / Associated Press) 47/61

The Iraqi-born British architect was the first woman to win the Pritzker Prize, architecture’s highest honor. She made her mark with buildings such as the London Aquatics Centre, the MAXXI museum for contemporary art in Rome and the innovative Bridge Pavilion in Zaragoza, Spain. She was 65. Full obituary

(Kevork Djansezian / Associated Press) 48/61

The former television talk show host became the first openly gay man to serve on the Los Angeles City Council. He advocated for the homeless, gays and lesbians and other liberal causes. He was 70. Full obituary

(Christina House / For The Times) 49/61

Garry Shandling’s comedic career spanned decades, but he is best known for his role as Larry Sanders, the host of a fictional talk show. His sitcom pushed the boundaries of TV, influencing shows such as “The Office” and “Modern Family.” He was 66. Full obituary.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 50/61

Ken Howard was president of SAG-AFTRA and an actor known for his role on TV’s ‘The White Shadow.’ He championed the merger of Hollywood’s two largest actors unions, which had a history of sparring. He was 71. Full obituary

(Al Seib / Los Angeles Times) 51/61

The longtime Los Angeles radio disc jockey, whose real name was Art Ferguson, hosted the morning radio show for popular and influential station KHJ-AM in the late 1960s and went on to be a key player in the launch of latter-day powerhouses KROQ-AM and KIIS-FM. He was 71. Full obituary

(Lawrence K. Ho / Los Angeles Times) 52/61

The veteran actor built his early career playing heavies and won an Academy Award in 1968 for his supporting role as the tough Southern prison-camp convict who grew to hero-worship Paul Newman’s defiant title character in “Cool Hand Luke.” He was 91. Full obituary

(Warner Bros. / Getty Images) 53/61

A prolific entrepreneur, Mann over the course of seven decades founded 17 companies in fields ranging from aerospace to pharmaceuticals to medical devices. He was 90. Full obituary

(Kirk McKoy / Los Angeles Times) 54/61

The Egyptian diplomat helped negotiate his country’s landmark peace deal with Israel but then clashed with the United States when he served a single term as U.N. secretary-general. He was 93. Full obituary

(Marty Lederhandler / Associated Press) 55/61

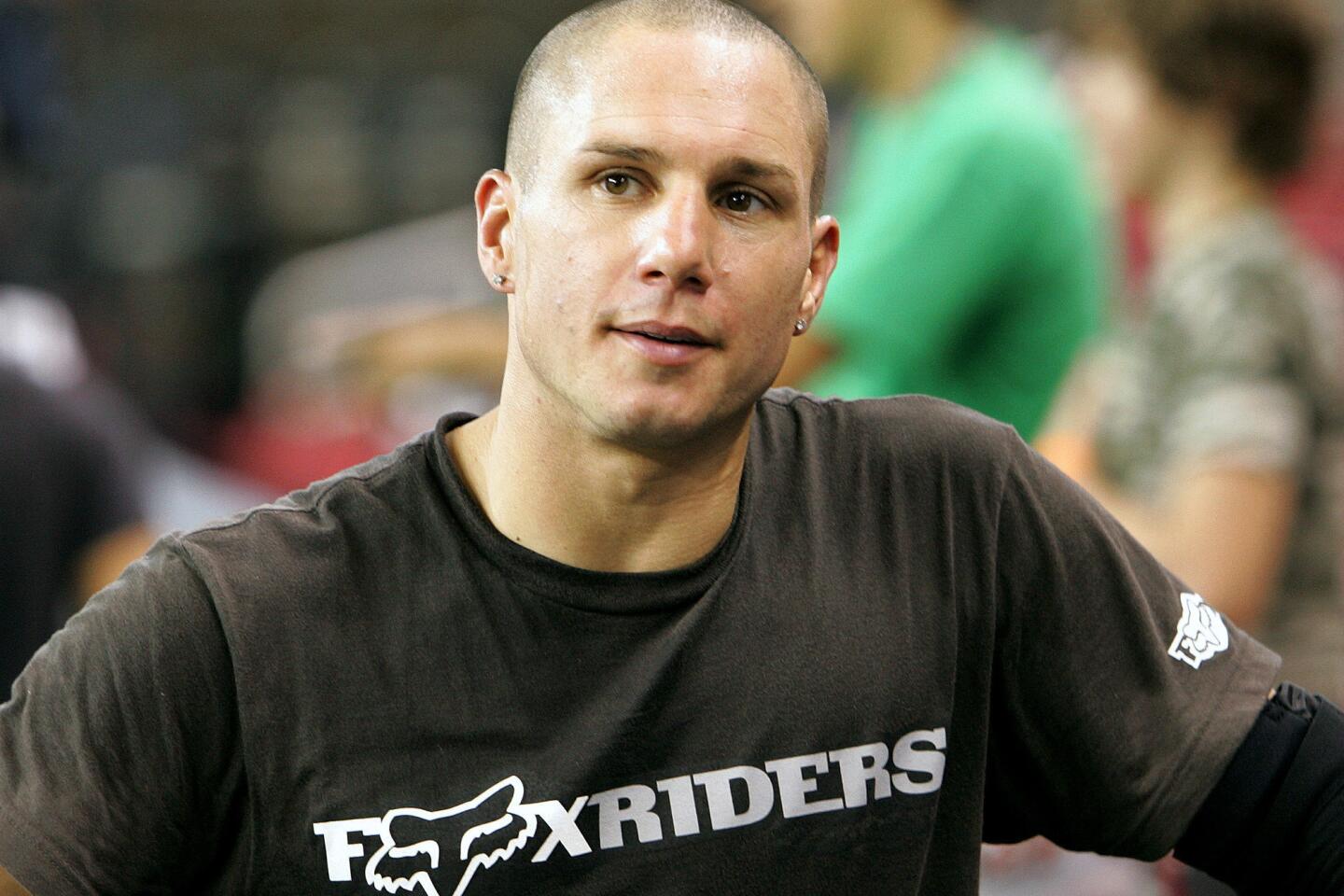

Pro-BMX biker Dave Mirra was one of the most decorated athletes in X Games history. He held the record for the most medals in history with 24. He was 41. Full obituary

(Ed Reinke / Associated Press) 56/61

Maurice White, co-founder and leader of the groundbreaking ensemble Earth, Wind & Fire, was the source for a wealth of euphoric hits in the 1970s and early ‘80s, including ‘Shining Star,’ ‘September,’ and ‘Boogie Wonderland.’ He was 74. Full obituary

(Kathy Willens / Associated Press) 57/61

In a career that encompassed everything from big-budget Hollywood movies to classical theater, Rickman made bad behavior fascinating to watch from “Die Hard” to the “Harry Potter” movies. He was 69. Full obituary

(Francine Orr / Los Angeles Times) 58/61

The composer and former principal conductor of the New York Philharmonic was known for pushing music lovers and the music establishment to let go of the past and embrace new sounds, structures and textures. He was 90. Full obituary

(Christophe Ena / Associated Press) 59/61

The Academy Award winner was revered as one of the most influential cinematographers in film history for his work on classics including “Close Encounters of the Third Kind” and “The Deer Hunter.” He was 85. Full obituary

(Tamas Kovacs / EPA) 60/61

Gordon helped revolutionize surfing with the creation of the foam surfboard. His polyurethane boards were lighter and easier to ride, making surfing accessible -- which helped popularize the sport globally. He was in his 70s. Full obituary

(Charlie Neuman / San Diego Union-Tribune/ZUMA Press) 61/61

The attorney and almond farmer was known for his battle to stop the $68-billion California bullet train project from slicing up his almond orchards -- part of a deeply emotional land war that has drawn in hundreds of farming families from Merced to Bakersfield. He was 92. Full obituary

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times) “We could have gone on from ‘Abbey Road,’” he said in a 1994 interview. “It was showing the way that rock ‘n’ roll and classical music could have joined forces to become something really important. And because we didn’t go on, punk came along and put everything into reverse.”

Martin is survived by his second wife, Judy, and four children, Bundy, Lucy, Gregory Paul and Giles.

[email protected]

Cromelin is a former Times staff writer.

------------

FOR THE RECORD

March 10, 11:28 a.m.: An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that George Martin won four Grammys. He won six.

------------

ALSO

Paul McCartney, Ringo Starr and Sean Ono Lennon remember Beatles producer George Martin

Nancy Reagan dies in Los Angeles at 94: Former first lady was President Reagan’s closest advisor

Elizabeth Garrett dies at 52; former USC provost was first woman president at Cornell University