‘Arnold Palmer invented pro golf as it exists today’: The sport’s greatest ambassador dies at 87

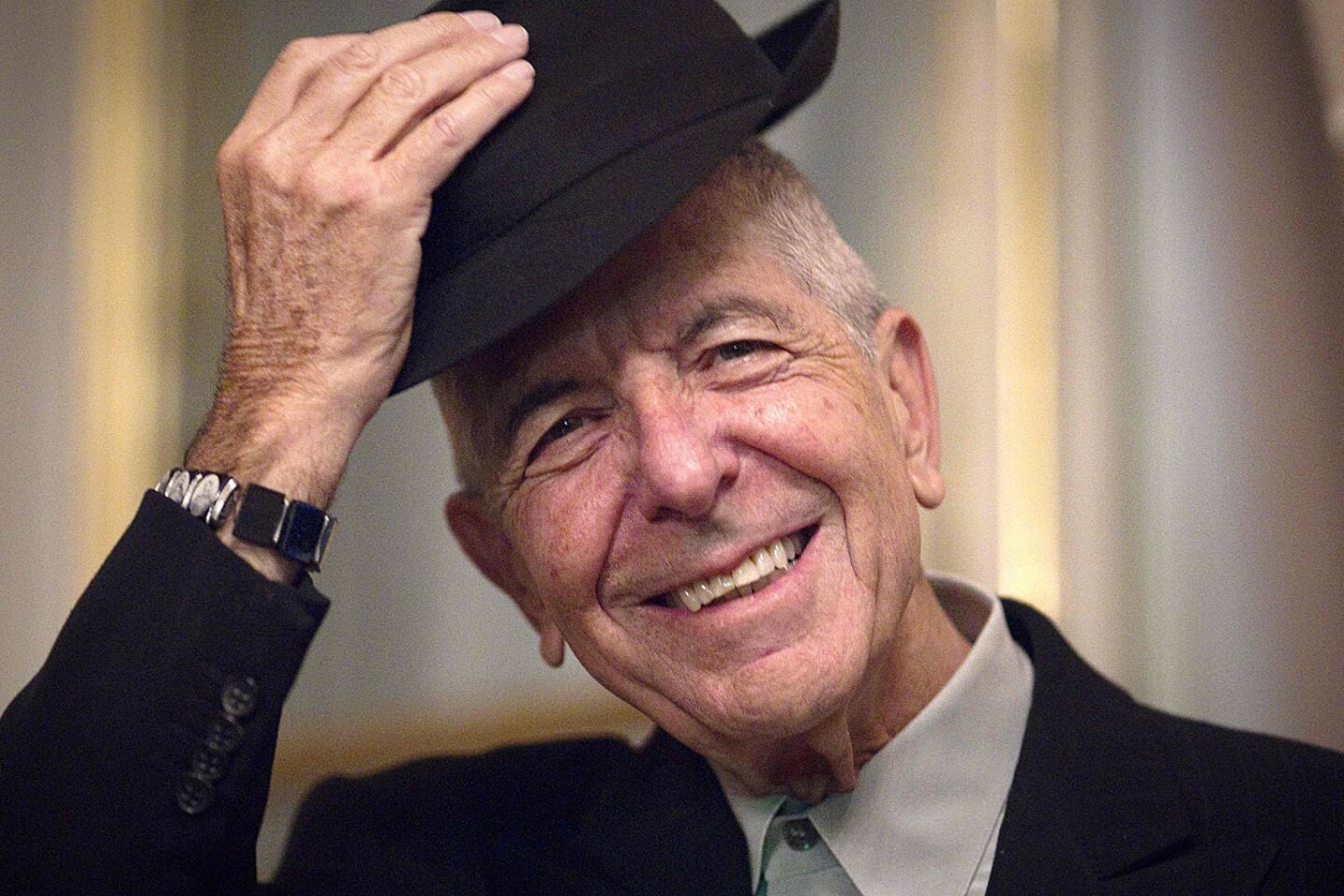

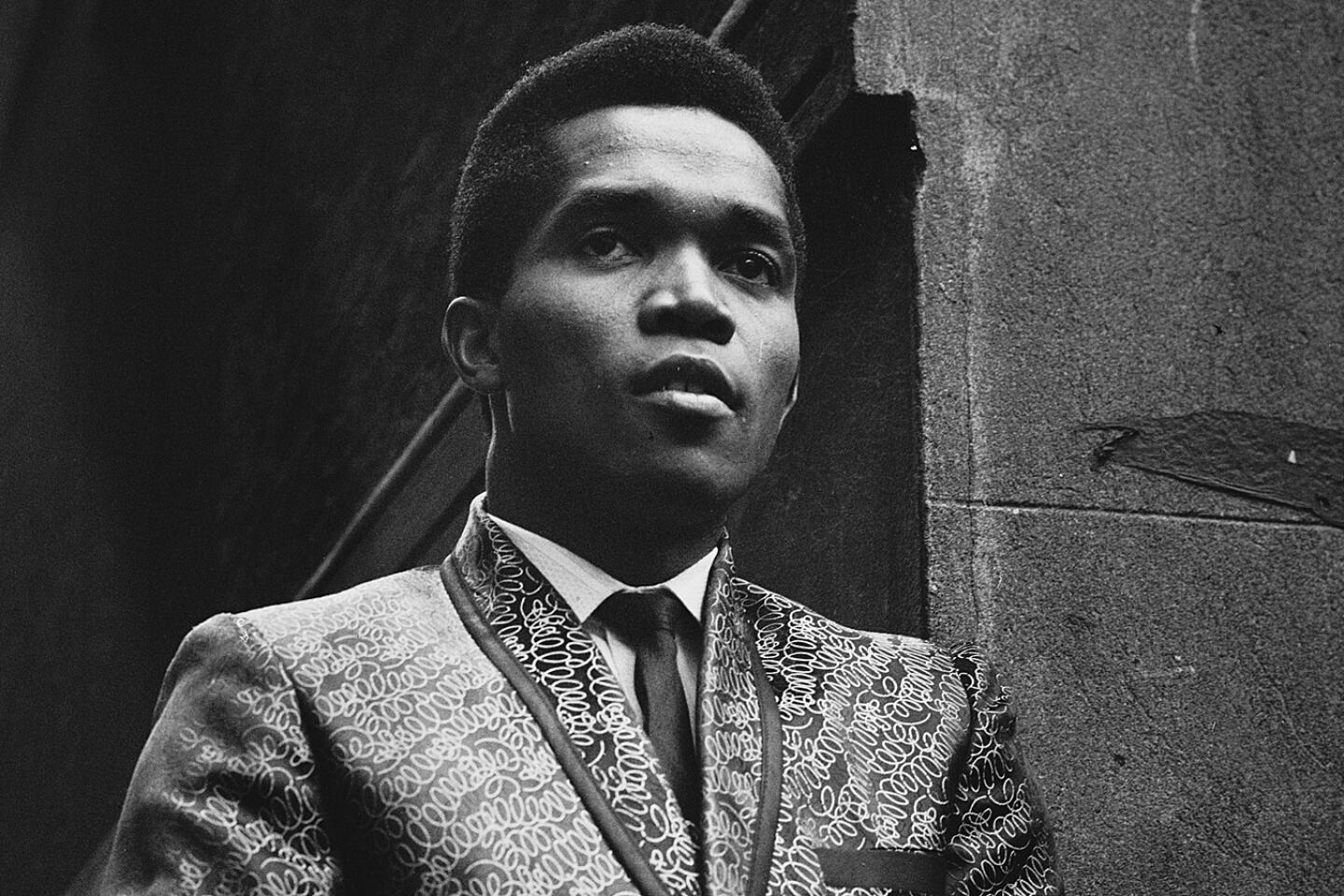

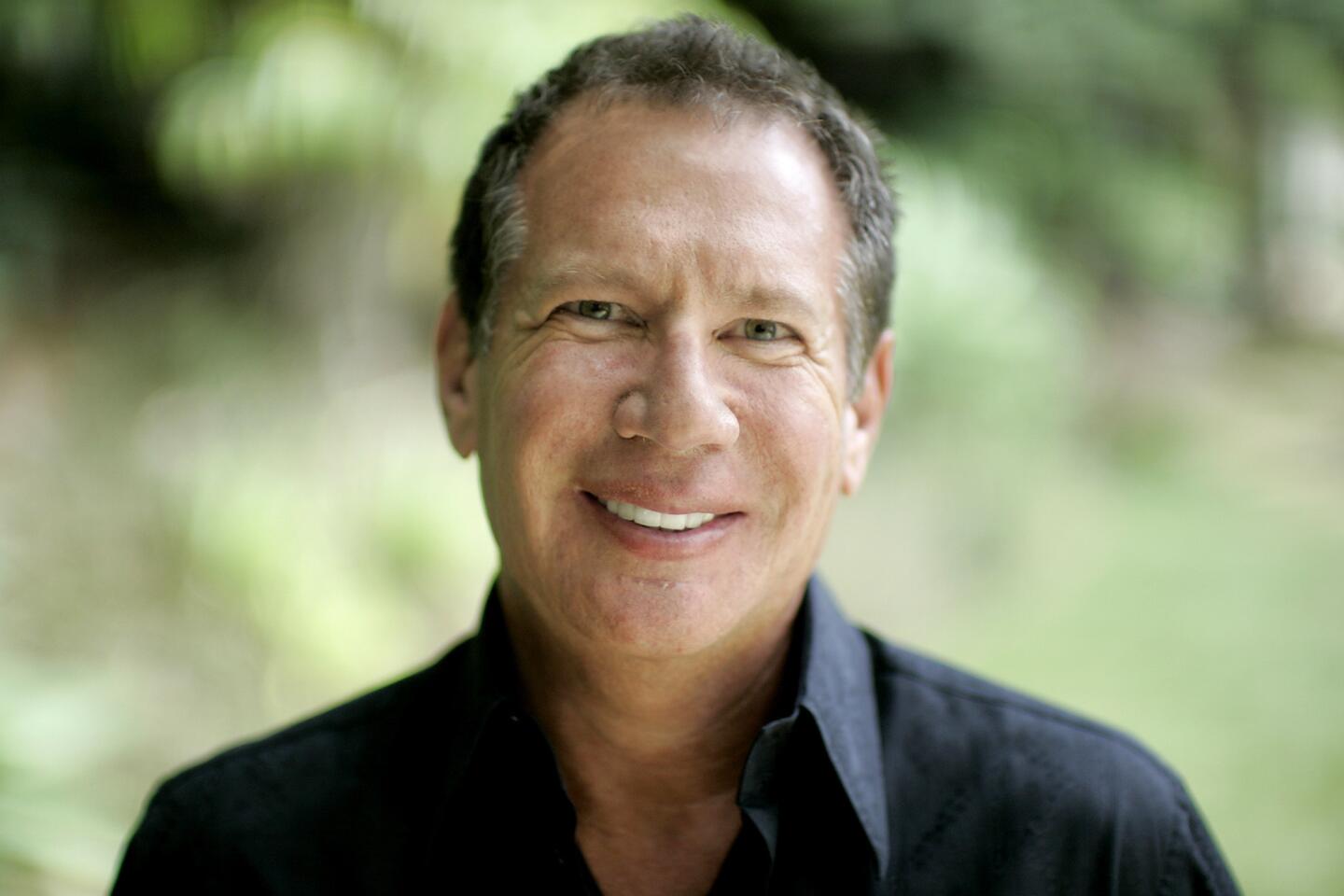

Arnold Palmer, the son of a Pennsylvania golf-course greens keeper who combined movie-star magnetism, go-for-broke daring and the nascent power of television to become a seven-time professional major tournament champion and the sport’s first international corporate icon, died Sunday. He was 87.

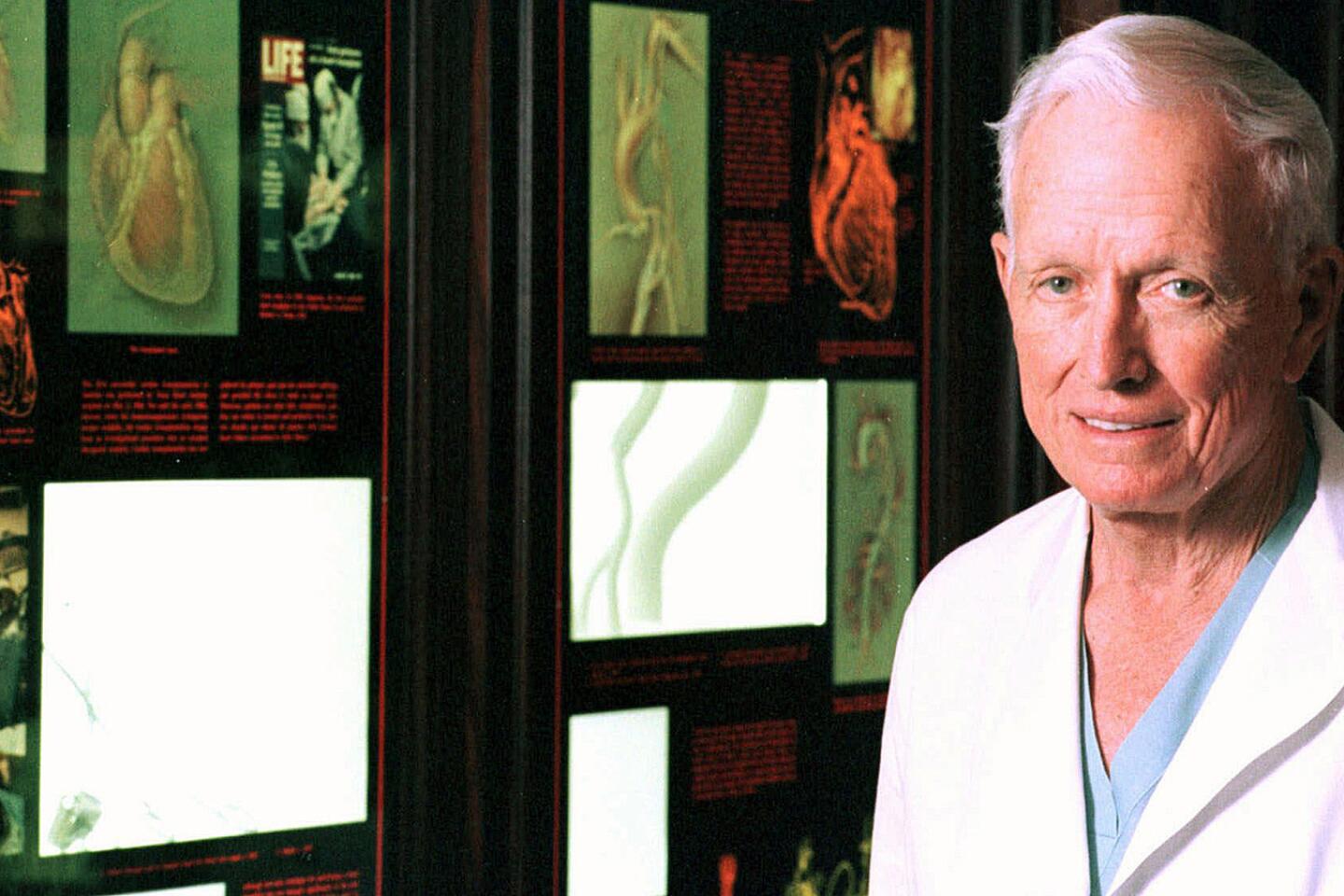

Alastair Johnson, chief executive of Arnold Palmer Enterprises, confirmed that Palmer died Sunday afternoon in Pittsburgh of complications from heart problems. Johnson said Palmer was admitted to the hospital Thursday for some cardiovascular work and weakened over the last few days. The United States Golf Assn. had also announced his passing on Twitter.

Palmer captivated golf audiences in the late 1950s and early 1960s with an ungainly, homemade swing and hitch-up-his-pants swagger. He won 62 PGA Tour events and more than 90 tournaments worldwide, but his swath cut far beyond fairways. He was not golf’s most accomplished star, as Jack Nicklaus, Tiger Woods, Walter Hagen, Ben Hogan, Gary Player and Tom Watson claimed more major victories.

Sam Snead compiled more PGA wins (82), while five players, but not Palmer, have captured golf’s modern career Grand Slam. (Palmer won four Masters titles, two British Opens and one U.S. Open, but he failed to win the PGA Championship.)

Yet it was Palmer who earned, and never relinquished, the sobriquet “King.” His impact on golf was unequivocal and transcendent. Armed with big biceps and a flat stomach, Palmer brought raw athleticism to a discipline many considered more skill than sport.

He revolutionized sports marketing as it is known today, and his success contributed to increased incomes for athletes across the sporting spectrum.

Palmer’s first professional major victory, at the 1958 Masters, serendipitously intersected with the phenomena of television. His chiseled looks and bold — some called it reckless — style of play made him a compelling lead actor in golf’s weekly playhouse theater.

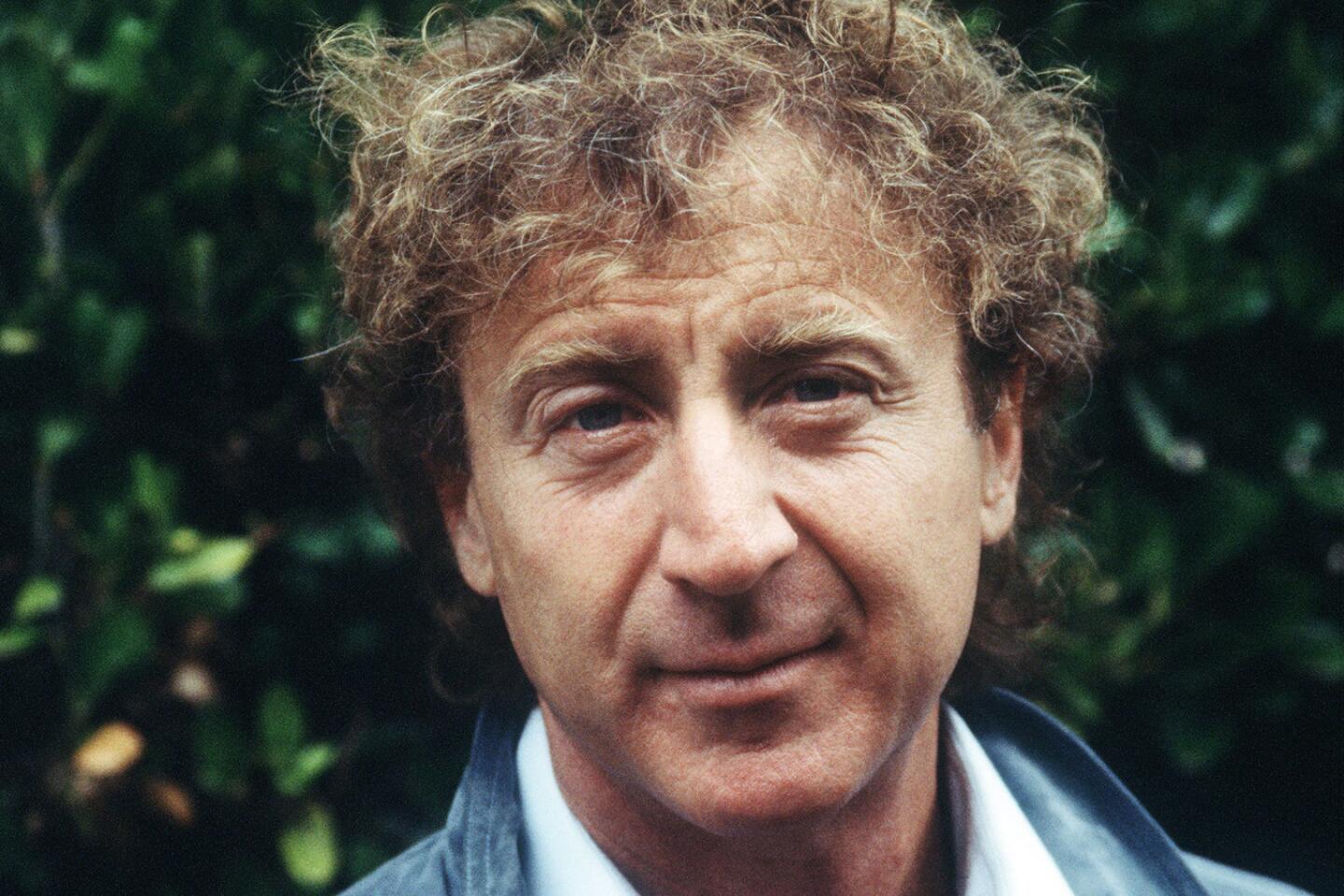

“Television and Palmer took over golf simultaneously,” Jim Murray, The Times’ Pulitzer Prize-winning sports columnist, once wrote.

Alastair Johnson, chief executive of Arnold Palmer Enterprises, confirmed that Arnold Palmer died Sunday of complications from heart problems.

Television and Palmer took over golf simultaneously.

— Jim Murray, Los Angeles Times columnist

Palmer’s historic victories were matched only by his historic collapses. The same man who rallied from seven shots behind on the final day to win the 1960 U.S. Open at Cherry Hills Country Club in Colorado also blew a final-day seven-shot lead to lose the 1966 U.S. Open at the Olympic Club in San Francisco.

“He was the Perils of Pauline,” Murray wrote. “Every round was a cliffhanger. Continued next week.”

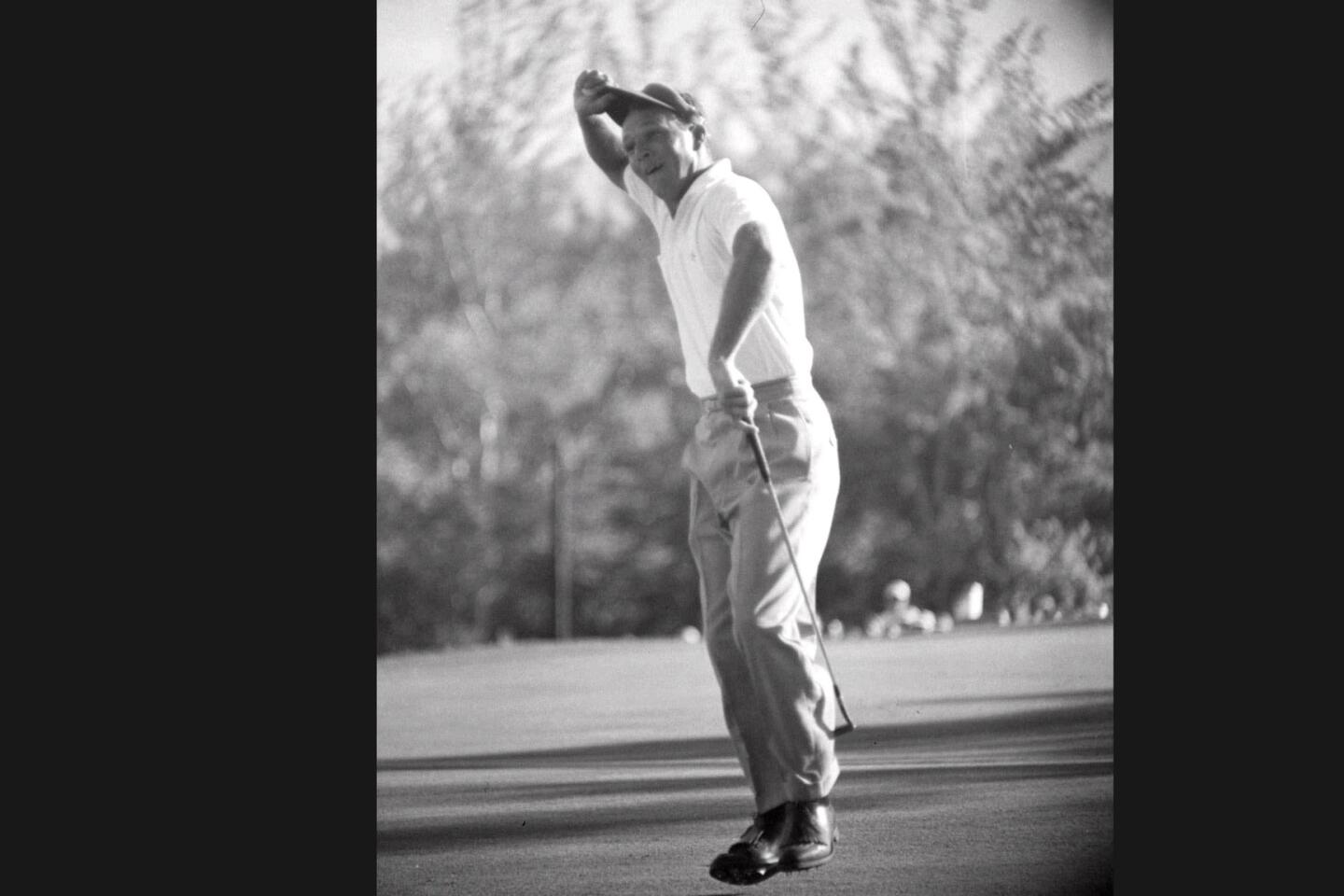

Palmer’s homemade, corkscrew swing — once likened to someone wrestling a snake — appealed to weekend hackers who also lacked textbook form.

“I was often where they were as I came down the stretch, in the rough, the trees, or up the creek,” Palmer wrote in his 1999 biography, “A Golfer’s Life.”

He boomed low-trajectory shots that might land, as Murray once described, “into a hole or the back of a convertible.”

Palmer chain-smoked L&M cigarettes (he later kicked the habit) and swigged Coca-Cola to calm his nerves — he would later endorse both products.

His putting could be sizzling hot or disastrously frigid. Palmer, sometimes to his detriment, never changed his attack approach.

“Critics who have said a safer shot here or there would undoubtedly have won me a few more tournaments are probably correct,” Palmer wrote, adding, “going for the green in two was who I was as a boy — and it’s who I remain as a man.”

Palmer maintained career-long eye contact with a devoted fan base known as “Arnie’s Army.” It was not uncommon for Palmer to chat up bystanders and reporters. Once, when confronted with an ugly lie in the bunker, Palmer solicited advice from Murray.

“OK, Jim,” Palmer said to The Times’ columnist, “you’re always writing about how great Ben Hogan was. How would Hogan do in a situation like this?”

Murray quipped: “Hogan wouldn’t have been in a situation like this.”

However, it was Palmer’s appeal to nongolfers, and women especially, that made him a crossover star. Television brought Palmer into Middle America’s living room, where he became a multimillionaire who never lost a connection to the common Joe.

“The camera is strange,” Frank Chirkinian, the longtime CBS golf producer who worked his first Masters in 1959, once told Golf Digest. “It’s all revealing. It either loves you or hates you, and it loved Arnold.”

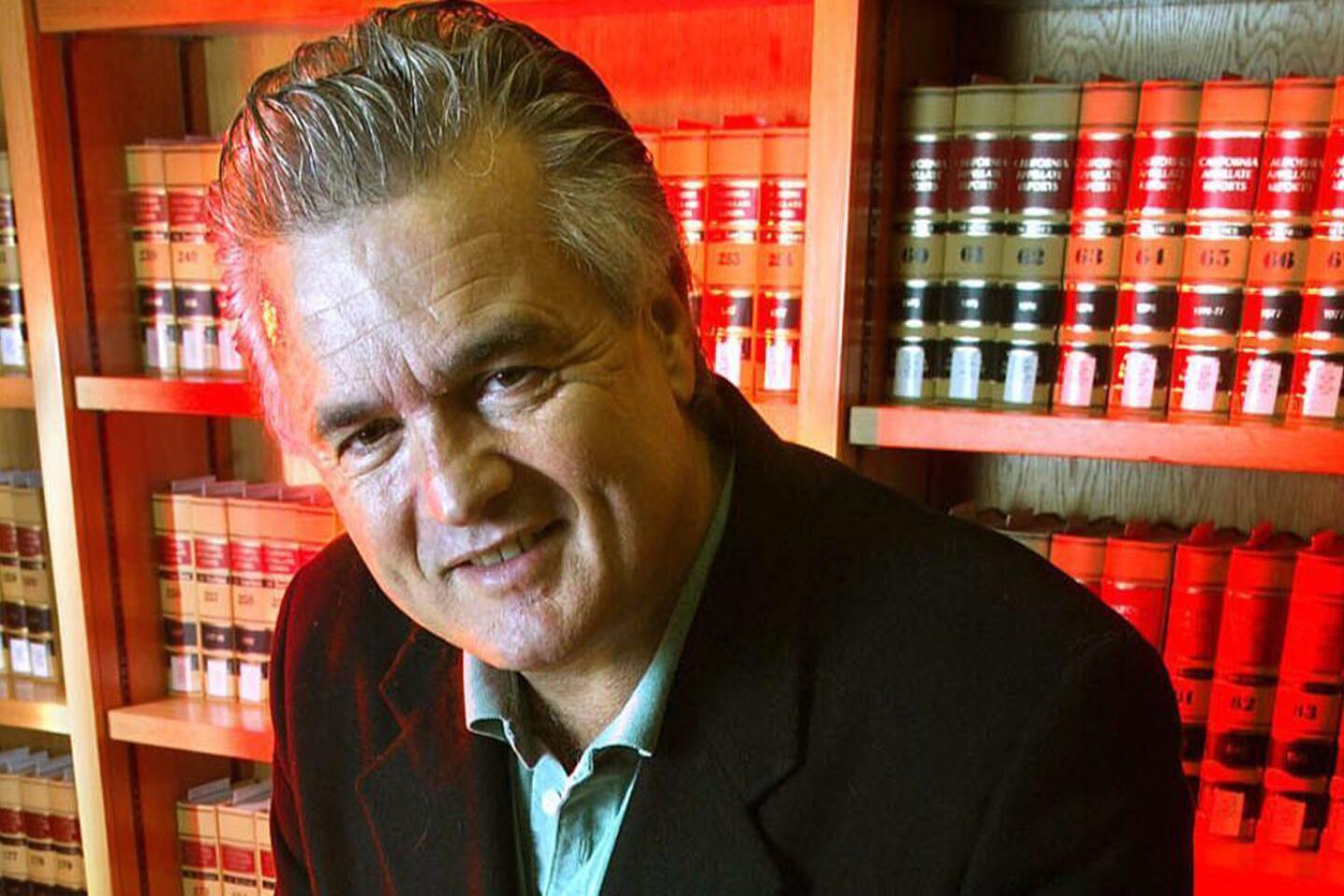

With a handshake agreement in 1960, Palmer joined forces with Mark McCormack and a fledgling company, International Management Group. The condition, at inception, was that Palmer would be McCormack’s only client.

McCormack helped promote Palmer’s brand into a corporate empire, while IMG grew to become a world-renowned sports, entertainment and media management company.

Palmer’s second Masters victory in 1960, punctuated with a birdie-birdie finish, sparked a dizzying array of income opportunities.

McCormack’s brilliance, Palmer once wrote, was not tying endorsements to his golf success. Under the umbrella of Arnold Palmer Enterprises, Palmer pitched sporting equipment, cars, clothing, insurance, soft drinks, cigarettes, and household and hardware products. He created his own chain of dry cleaner centers.

Palmer had his limits, once turning down a chance to promote what he called “a revolutionary manure dispenser.”

Palmer insisted, he said, on promoting products he used or believed in. That tractor he rode in those popular TV commercials was his father’s, and it ran on Pennzoil long before the endorsement deal was signed.

Palmer obtained his pilot’s license and became a true jet-setter, zigzagging across the globe to promote his interests. He hobnobbed, golfed and dined with entertainers, dignitaries and presidents, developing close friendships with entertainer Bob Hope and President Dwight D. Eisenhower.

In 1966, as part of a well-kept secret to mark his 37th birthday, Palmer received a surprise knock on his door at his home in Latrobe, Pa.

“You wouldn’t have a room to put up an old man for the night, would you?” the man, carrying an overnight bag, wondered.

It was Eisenhower.

Palmer was so popular he once guest-hosted for Johnny Carson on “The Tonight Show,” and one of his favorite beverages, a mix of ice tea and lemonade, became a bar drink still known as an “Arnold Palmer.”

The apex of Palmer’s golfing powers was relatively short. He won all seven of his professional majors between 1958 and 1964.

Palmer’s last PGA Tour victory was at the 1973 Bob Hope Classic, yet his popularity and earning power never waned.

Tiger Woods is helped into his winner’s jacket by golfing great Arnold Palmer after taking a victory at the 2001 Bay Hill Invitational in Orlando, Fla.

At age 79, Palmer ranked No. 4 on Golf Digest’s 2008 list of top 50 money makers with yearly earnings of more than $30 million. He trailed only three active players on the PGA Tour — Woods, Phil Mickelson and Vijay Singh.

“Arnold Palmer invented pro golf as it exists today,” sportswriter Rick Reilly once wrote. “Ben Hogan didn’t make golf popular. Hogan was as much fun to cuddle as a porcupine. Nicklaus didn’t do it.... Palmer’s the King. He’s the one who made it all possible.”

Arnold Daniel Palmer was born in Youngstown, Pa., on Sept. 10, 1929 — not too soon before the stock market crashed. He was the oldest of four children by Deacon and Doris Palmer.

The Palmers lived in nearby Latrobe, where Deacon provided golf lessons and served as greens keeper at Latrobe Country Club. Arnold couldn’t swim in the pool or play golf while members were present, a slight he rectified in 1971 by purchasing the club.

As a boy, Palmer earned money shagging balls and sneaked practice shots at every available chance. Becoming a caddie later enabled him to play Mondays, when the course was closed.

Palmer had large, strong hands, and he used them to fashion a vise-like grip and a powerful, unorthodox swing. Palmer wrote in his autobiography that his father, a tough disciplinarian, told him not to complicate things.

“Hit it hard, boy,” he said simply. “Go find it and hit it hard again.”

“Deke” Palmer never allowed anyone to tinker with Arnold’s mechanics.

As Palmer’s game evolved, he played out dramatic U.S. Open finishes in his back-nine imagination. He read books on his golf heroes, Bobby Jones in particular.

“Golf would be my ticket somewhere, I told myself,” Palmer wrote. “I just couldn’t say where it would lead me.”

At Latrobe High School, he won consecutive Pennsylvania schoolboy championships before following his friend Buddy Worsham to play golf at Wake Forest University.

Palmer emerged as a top collegiate player, but his time in North Carolina was cut short when, in 1950, Worsham was killed in an automobile accident.

Palmer was devastated. “Wake without Bud was unthinkable,” he would later recount. Palmer finished out the school term and then joined the Coast Guard, where he spent three years before returning to Wake Forest. He won the Atlantic Coast Conference golf championship but left before completing his degree.

The turning point of his career came with his victory at the 1954 United States Amateur Championship at the Country Club of Detroit — Palmer always considered it his “eighth” major.

Palmer’s father, not one to lavish praise, told Arnold afterward: “You did pretty good, boy.”

Arnold wrote that his heart swelled “nearly to the breaking point.”

Palmer would not continue his day job — selling paint.

Not long after his U.S. Amateur victory, Palmer fell smitten with 19-year-old Winifred “Winnie” Walzer, whom he encountered at a tournament in Pennsylvania.

“I met him on Tuesday, he asked me to marry him on Saturday,” Winnie once said. The Palmers were married 45 years before her death, at age 65, in 1999.

It was a whirlwind courtship, to say the least.

The couple eloped in 1954 and Palmer, using borrowed money, turned professional. The PGA of America in those days prohibited rookies from earning prize money during their first six months on tour — an edict that chafed Palmer for years and complicated his relationship with the organization that staged the only major championship he wouldn’t win.

Winnie kept the family books as the newlyweds toured the circuit, living in a trailer pulled by a coral pink Ford. Palmer won his first tournament, the Canadian Open, in 1955 and garnered $7,958 that year in prize money.

He won four tournaments each of the next two years before a major breakthrough at the 1958 Masters, his final-day eagle at the par-5 13th hole foretelling his penchant for dramatics.

“Arnold Palmer was born April 6, 1958, on the back nine of Augusta National Golf Club,” Sports Illustrated would later reflect.

Palmer was motivated after overhearing Hogan say to a fellow player in the clubhouse before the tournament: “How the hell did Palmer get an invitation to the Masters?”

The comment hurt Palmer, and the two legends were never friends.

Palmer’s love affair with the Masters lasted a half-century. He won the event four times — 1958, 1960, 1962 and 1964. He played in 50 consecutive events before taking final bows in 2004. Only Gary Player, with 51, has more Masters’ appearances.

It was at Augusta in the late 1950s that “Arnie’s Army” was first enlisted to lead Palmer’s many “charges.” The tournament then used volunteer soldiers from nearby Camp Gordon (later renamed Ft. Gordon) to man the scoreboards. Palmer recalled seeing one of men holding a small “Arnie’s Army” sign.

“I found out they were guys that had actually taken leave,” Palmer recounted at his final Masters news conference. “They weren’t just given permission to come out there and do that ... and it expanded from there.”

The Masters may have been Palmer’s favorite tournament, but it wasn’t always kind to him.

In 1959, he blew a back-nine lead on Sunday and lost to Art Wall. Two years later, needing par on the final hole to become the first player to win consecutive Masters, Palmer made double-bogey 6 and handed Player his first green jacket.

It was all part of being Arnold Palmer, once described by a writer as “that cataclysm with legs.”

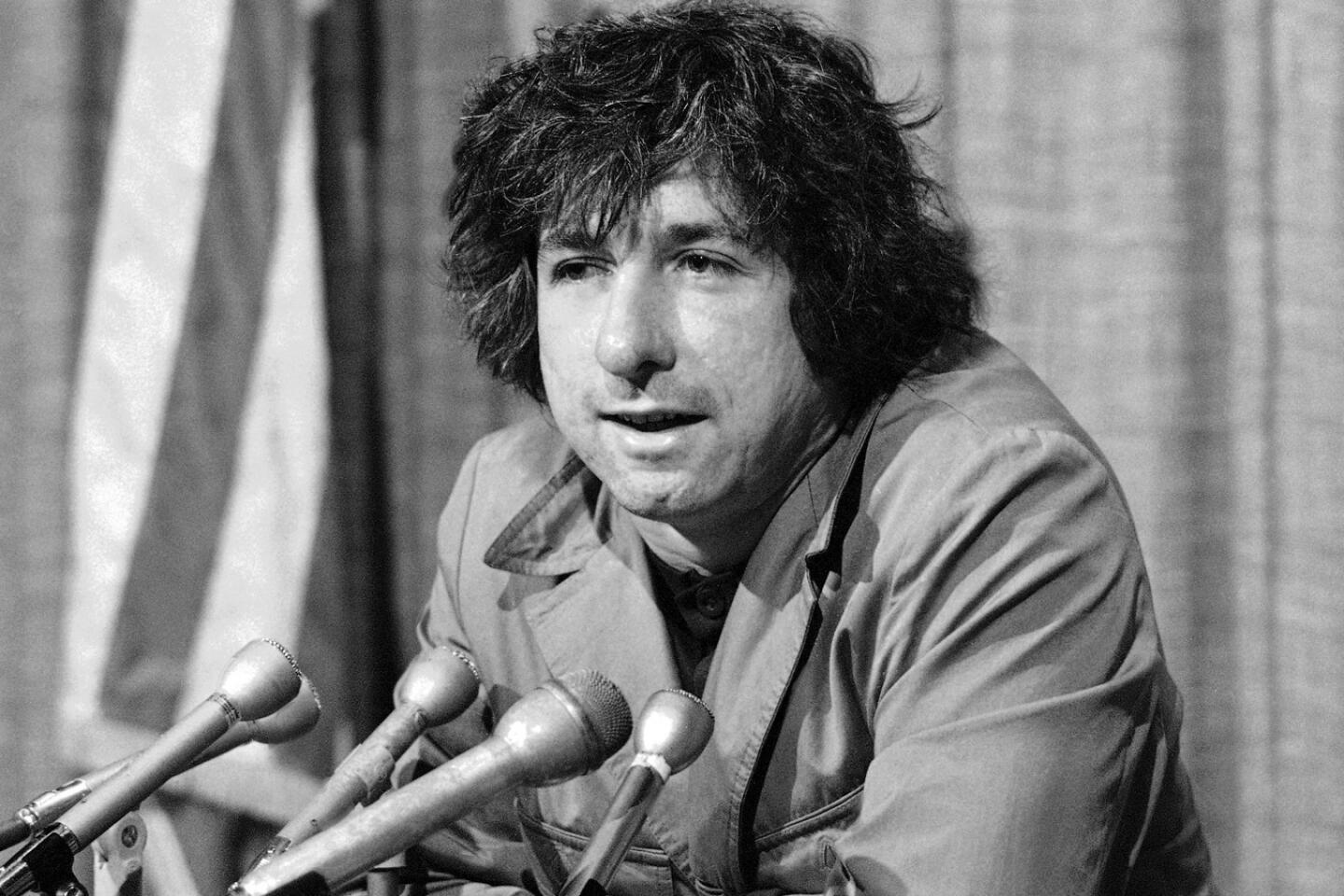

Beginning in 1960, Palmer ushered in what has been called golf’s Golden Era. He followed his Masters victory that year with a stunning comeback at Cherry Hills to win his only U.S. Open. Palmer entered the final round trailing leader Mike Souchak by seven shots — with 13 players separating Palmer from the leader.

Palmer walked into the clubhouse between the third and fourth rounds — both were played Saturday in those days — and stumbled upon sportswriters Dan Jenkins and Bob Drum.

Palmer wondered out loud if a final-round 65 would give him a chance to win.

“You’re too far back,” Drum, who had chronicled Palmer’s rise for the Pittsburgh Press, said.

As he recounted in his autobiography, Palmer uttered the line “watch and see.”

Palmer shot exactly 65 to hold off Hogan and a cherubic amateur from Ohio named Nicklaus.

Palmer became golf’s “king” in 1960, his watershed year. He won two majors — and eight tournaments overall — and was credited for making the British Open important again in the United States. Many American players in the 1950s thought it cost-prohibitive to play overseas, but Palmer considered the British Open an essential cog in the modern Grand Slam.

Palmer finished second at the British on his first trip in 1960, and won the event the next two years.

“It was a nice championship to place on a list of achievements but not an essential one,” the London Independent wrote of American indifference to the event. “ ... Palmer, almost single-handedly, changed all that.”

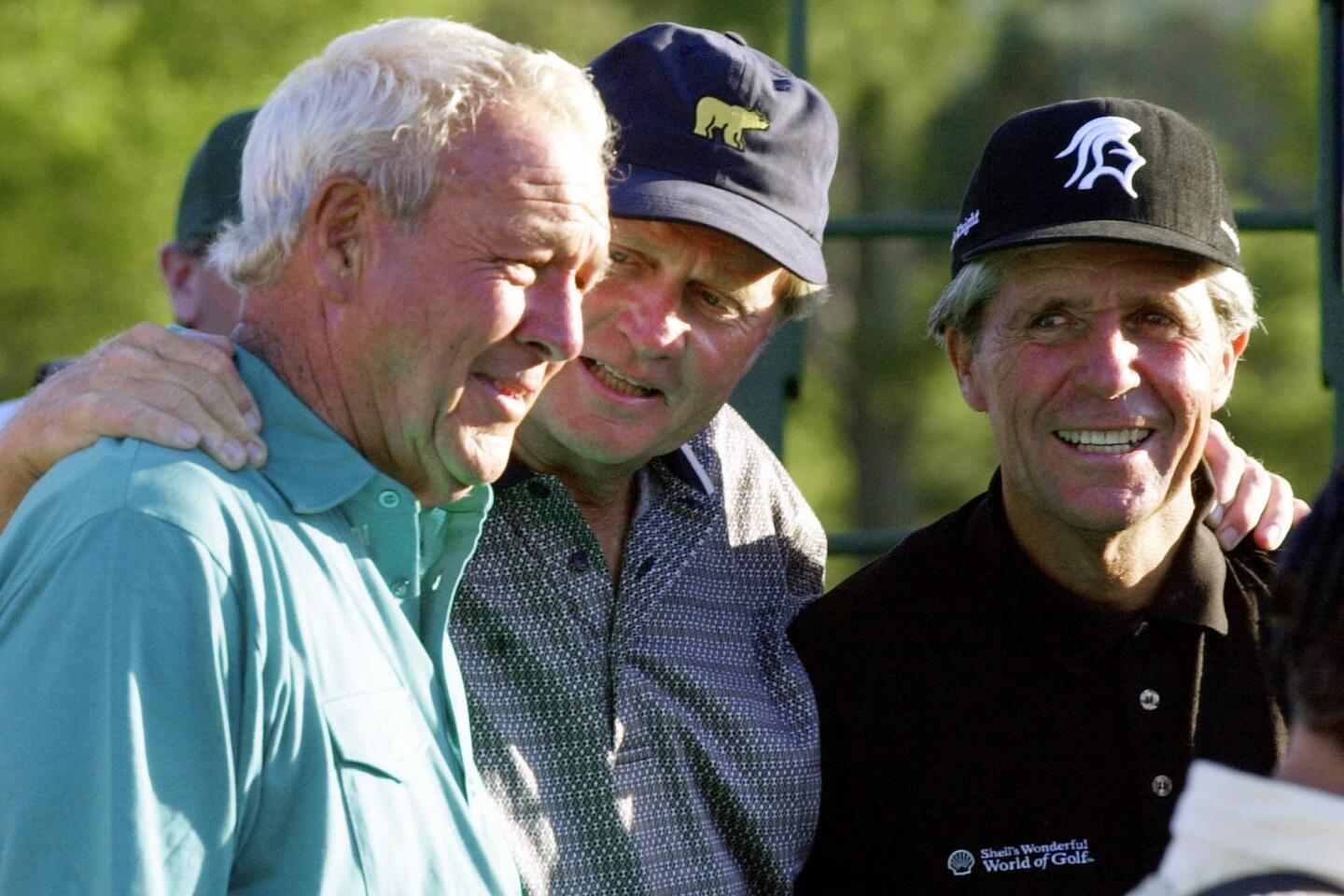

Palmer won 29 events between 1960 and 1963, but two fast risers on the circuit, Player and Nicklaus, would eat into the King’s dominance and create a triple threat known as golf’s Big Three.

Palmer’s rivalry with Player and Nicklaus — especially Nicklaus — endured years and helped fuel the sport’s increasing popularity.

“We knew we were good theater — and we enjoyed it at least as much as the fans and reporters did,” Palmer wrote. “But most of all, we wanted to beat each other to a pulp.”

In what many considered a major turning point in golf’s transfer of power, Nicklaus in 1962 ventured into Pennsylvania Palmer Country and defeated the King in a playoff to win the U.S. Open at Oakmont Country Club.

“You’d better watch the fat boy,” Palmer had warned writers before the tournament.

Nicklaus would eclipse Palmer as the game’s top player and go on to win 18 professional majors. Their relationship was complicated, cordial and fiercely competitive.

Palmer did not win another major after the 1964 Masters.

In the 1966 U.S. Open at the Olympic Club, however, he incredibly blew a seven-shot lead with nine holes left and lost a next-day playoff to Billy Casper.

Palmer admitted he quit playing the contenders in his pursuit to break Hogan’s U.S. Open record shot total of 276.

Palmer lost three U.S. Opens in playoffs and finished tied for second three times at the PGA Championship. The chapter on the PGA in Palmer’s biography is fittingly titled: “Missing Link.”

Palmer confessed that tending to his burgeoning business empire may have taken a toll on his golf game. After 1962, he also gave up smoking regularly on the course, which may have affected his nerves.

Palmer, though, never surrendered his icon status. He continued to build his businesses, design golf courses and serve as the sport’s preeminent advocate and ambassador. He was awarded the Congressional Gold Medal in 2009.

He was instrumental in forming the PGA’s Senior (now Champions) Tour for golfers past the age of 50. He even flashed glimpses of previous greatness by winning the PGA Seniors Championship in 1980 and the Senior U.S. Open a year later.

His final senior tour victory came at the 1988 Crostar Classic. He played his last U.S. Open and PGA Championship in 1994, and his final British Open in 1995.

Palmer overcame prostate cancer in the late 1990s and resumed his playing career then officially retired from competitive golf Oct. 12, 2006, withdrawing after four holes of the Administaff Small Business Classic.

Not surprisingly, Palmer completed the round so as to not disappoint fans who had come see him play.

In a 1985 interview with The Times, Palmer said he never forgot his humble beginnings.

“I grew up in poverty on the edge of a golf course,” he said. “I saw how people lived on the other side of the tracks, the upper crust and the WASPs at the country club. We had chickens and pigs in our yards. We butchered every year. I’ll never forget those things.”

Palmer also hated the moniker bestowed on him.

“There is no king of golf,” he once scoffed. “Never has been, never will be. Golf is the most democratic game on Earth.... It punishes and exalts us all with splendid equal opportunity.”

Palmer and Walzer had two daughters, and grandson Sam Saunders plays on the PGA Tour. Palmer married Kathleen “Kit” Gawthrop in 2005.

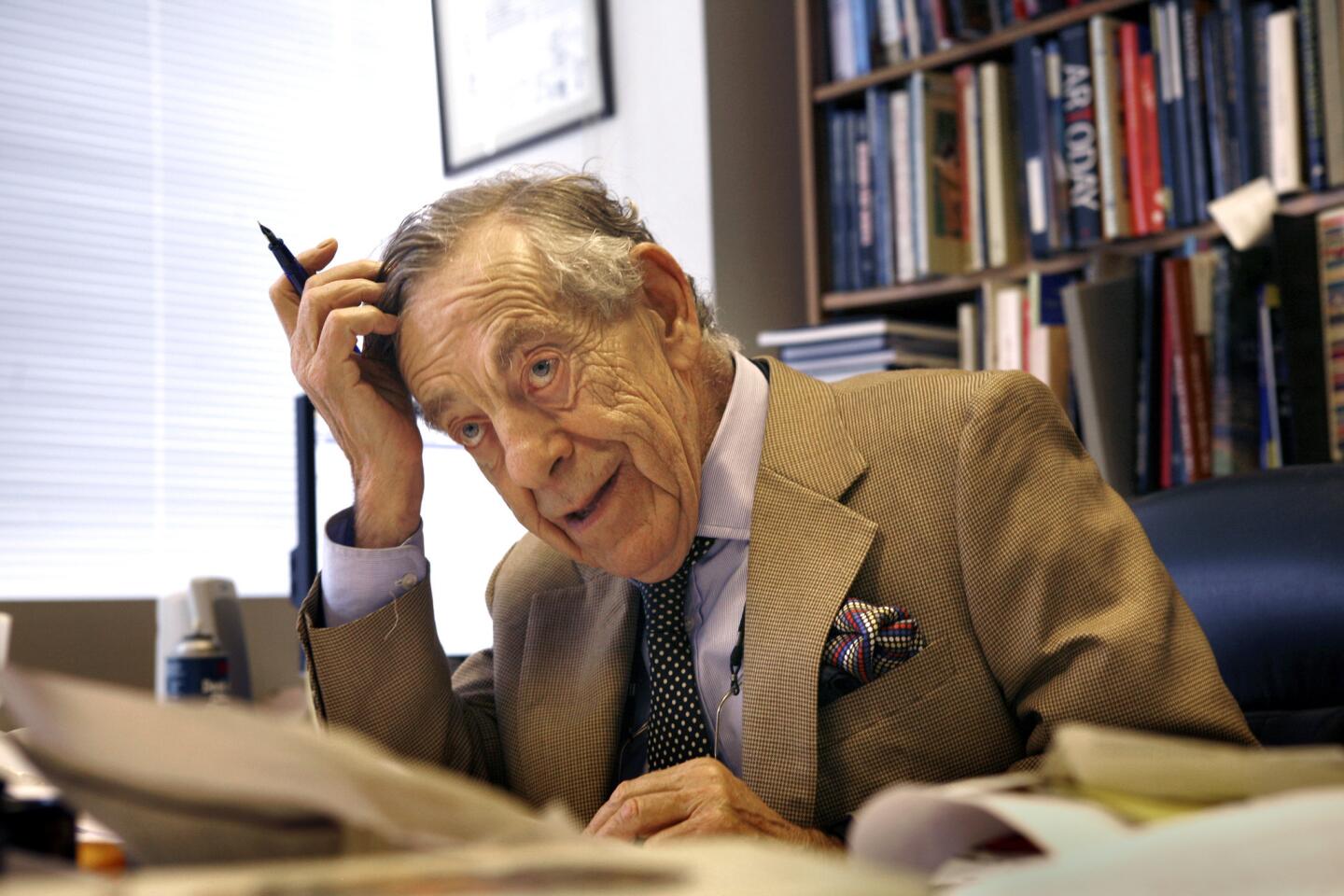

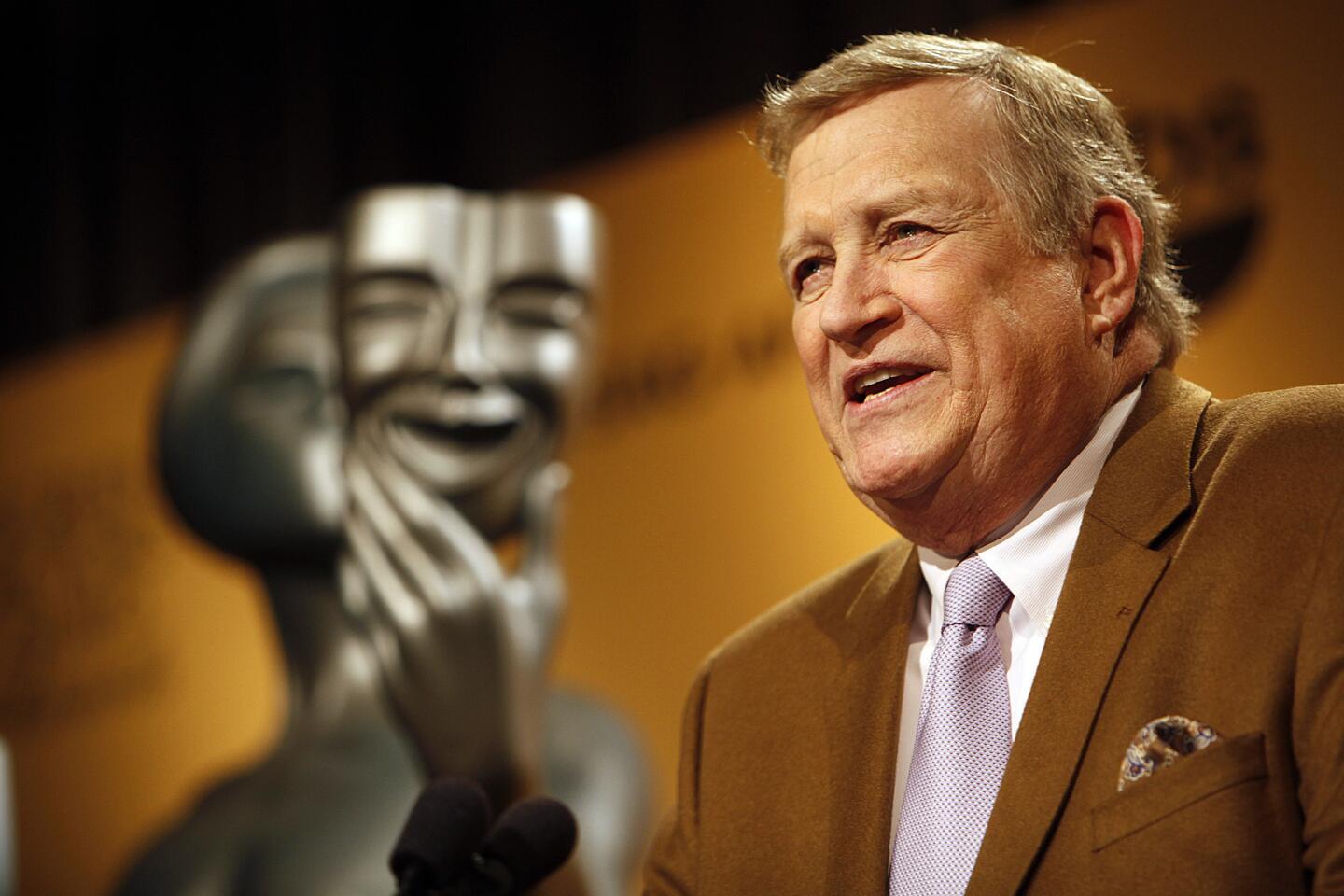

Vin Scully final press conference

Vin Scully's Final Press Conference Part One (of Four)

Vin Scully's Final Press Conference Part Two (of Four)

Vin Scully's Final Press Conference Part Three (of Four)

Vin Scully's Final Press Conference Part Four

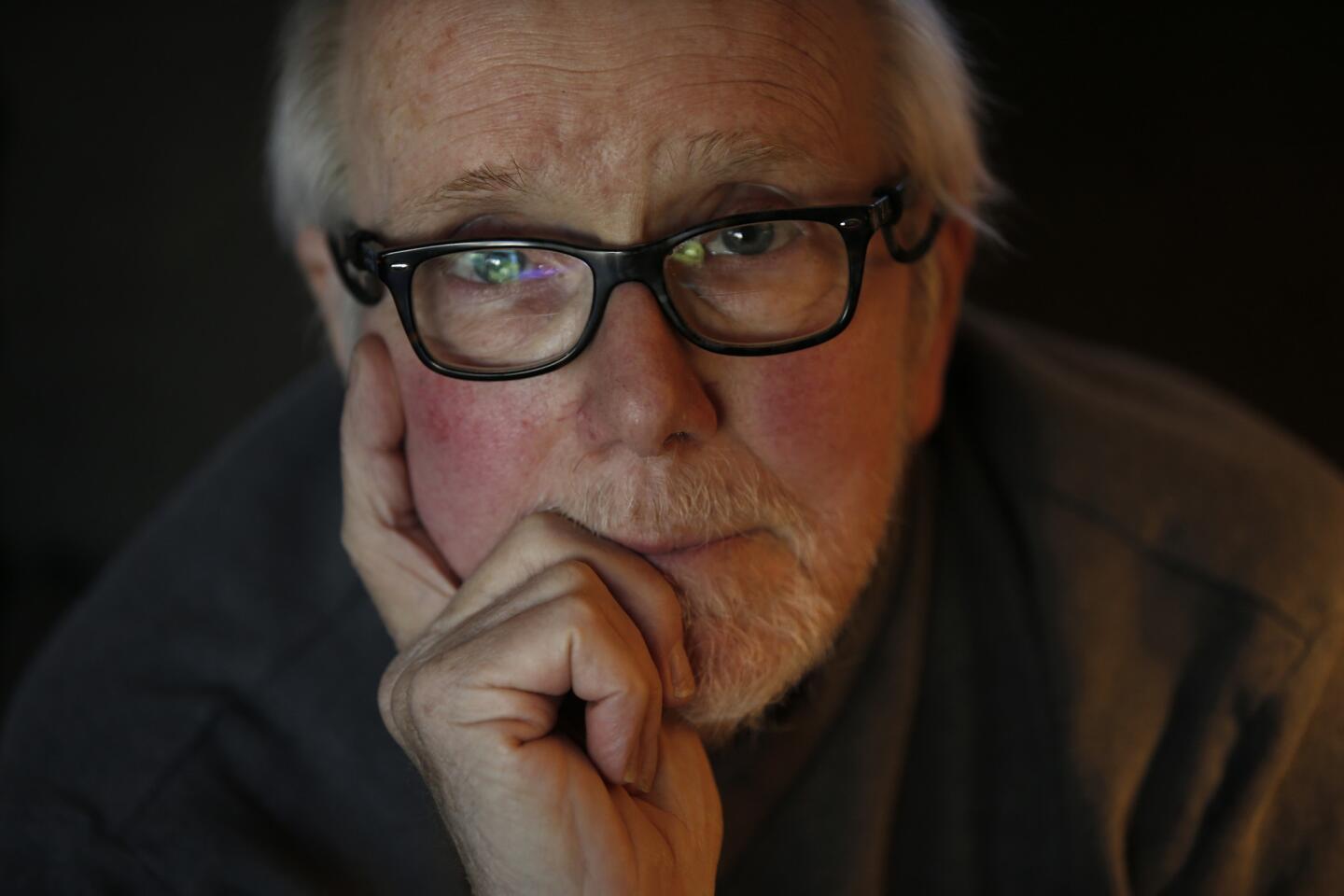

Dufresne is a former Times staff writer. The Associated Press contributed to this report.

ALSO

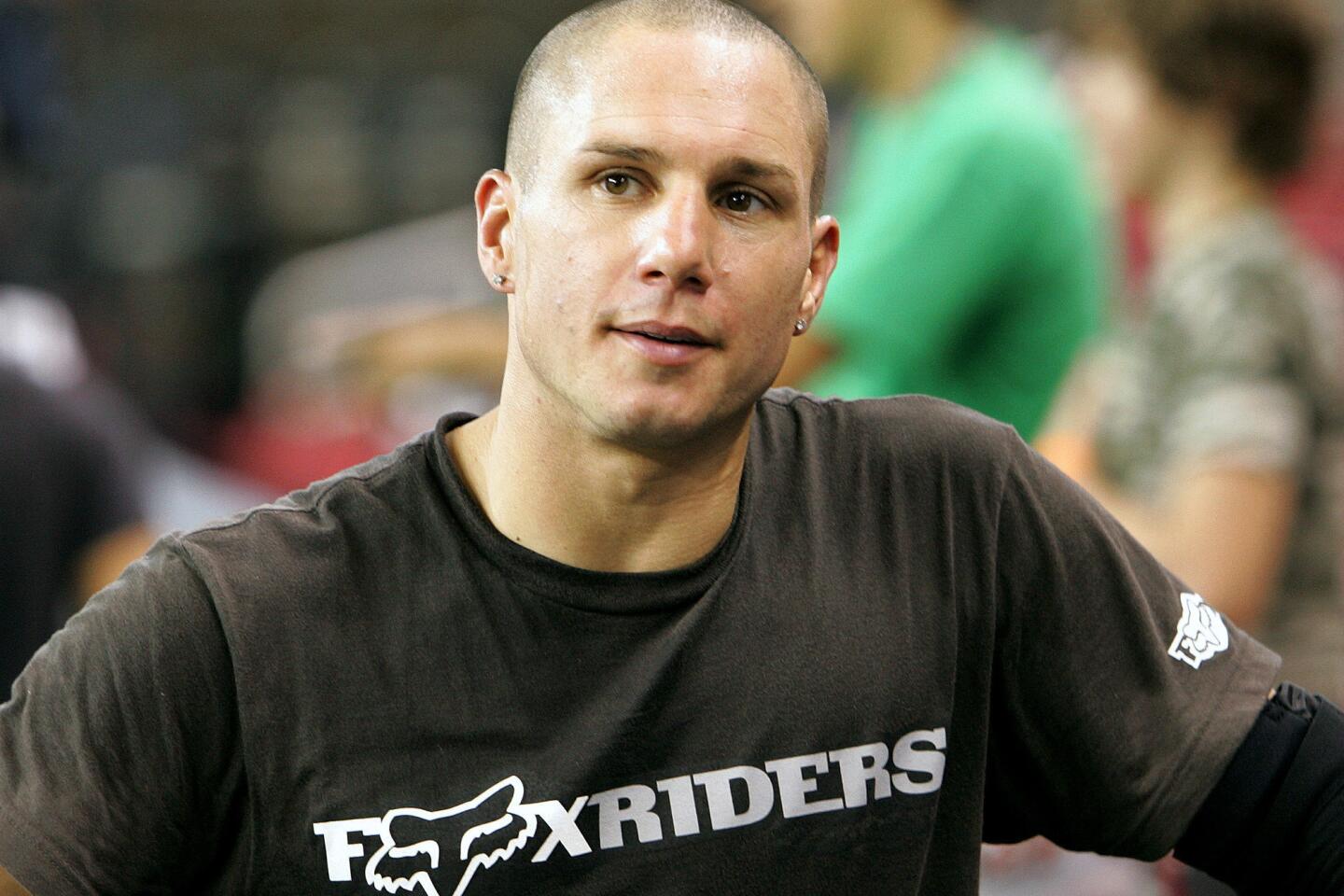

Commentary: Jose Fernandez’s death is especially heartbreaking for Cubans and Cuban Americans

Bill Plaschke: Vin Scully is a voice for the ages

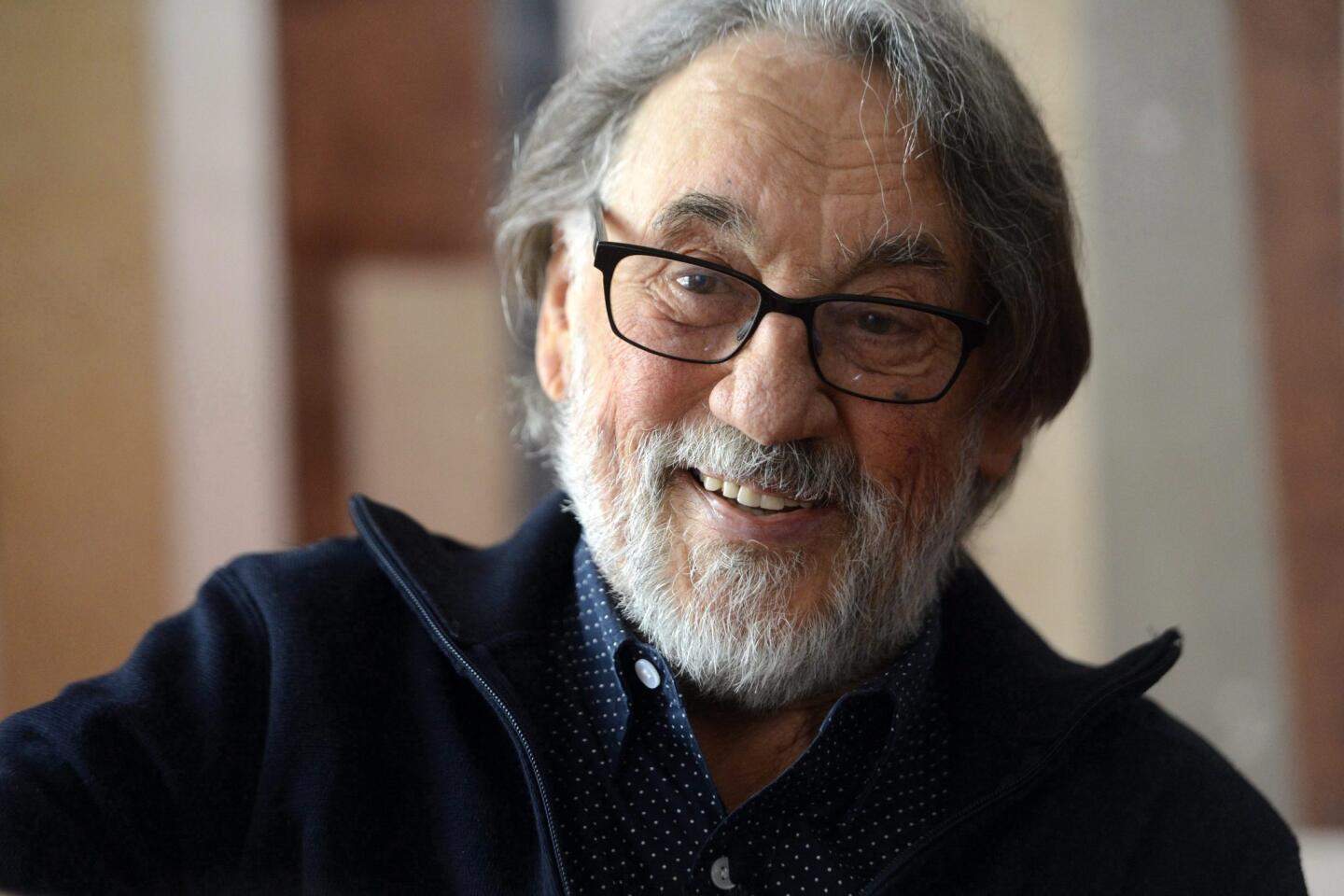

Gabriele Amorth, Roman Catholic priest known as the Vatican’s exorcist, dies at 91

UPDATES:

7:05 p.m.: This article was updated with confirmation of Palmer’s death by Alastair Johnson and details about survivors.

This article was originally published at 6:05 p.m.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.