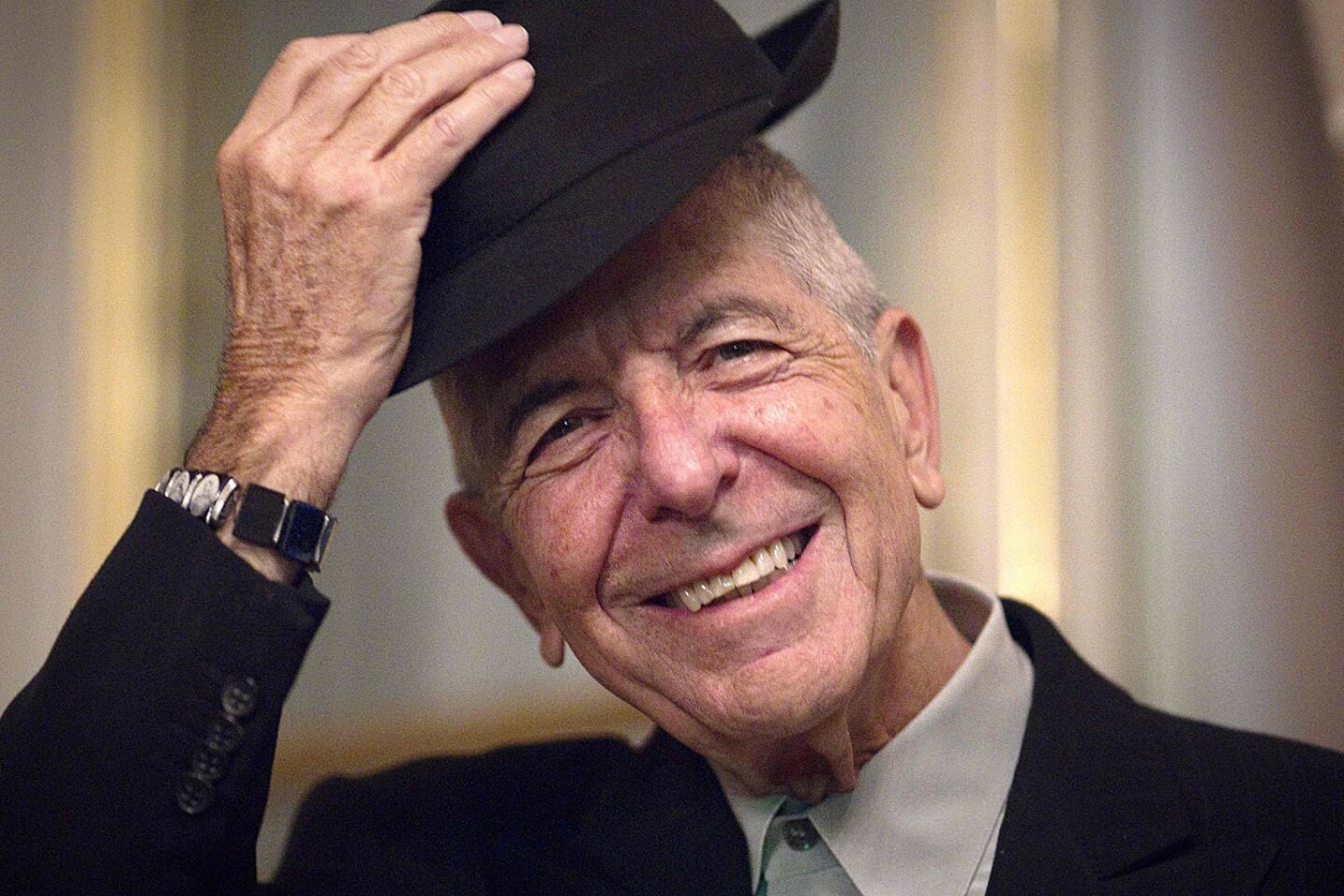

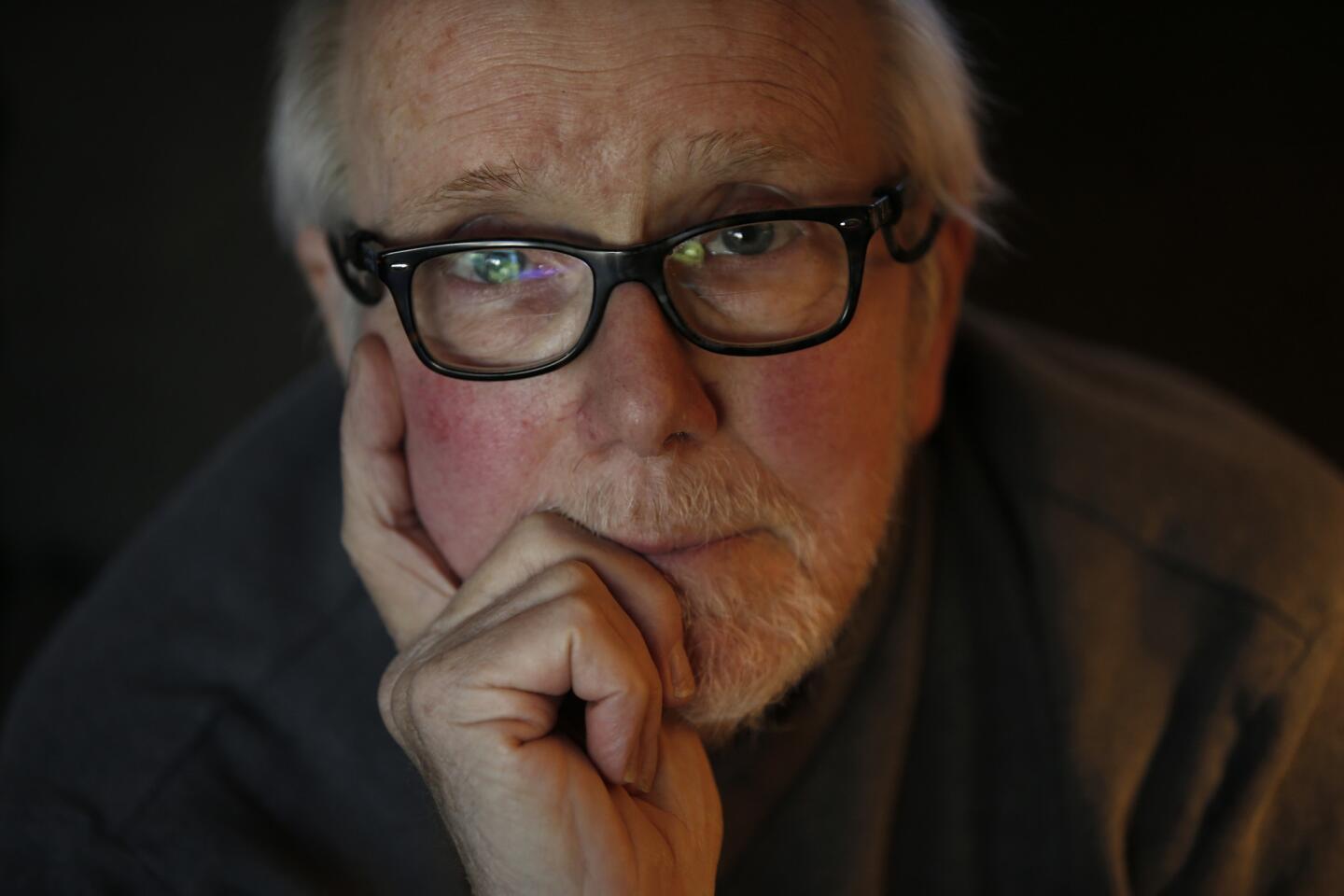

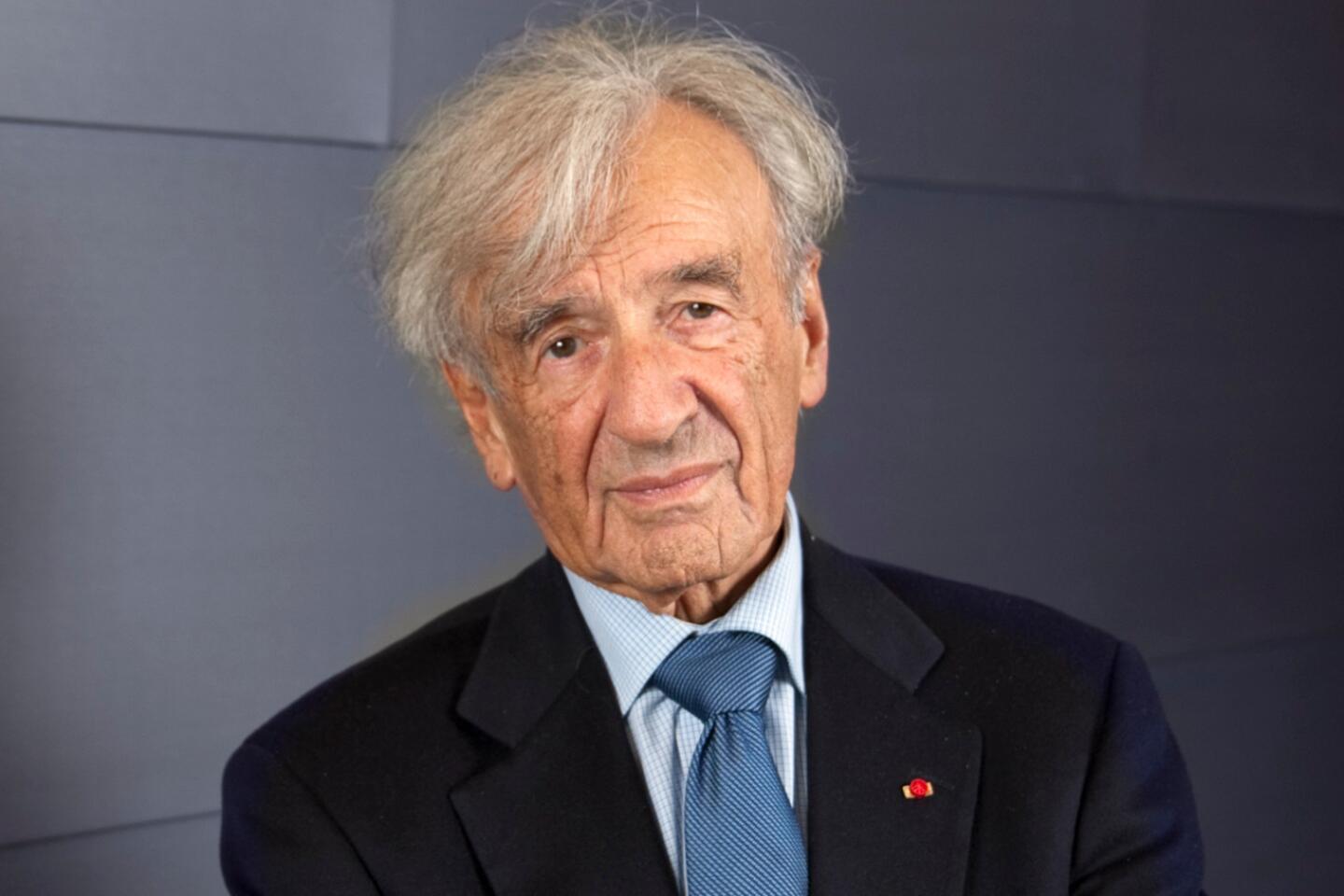

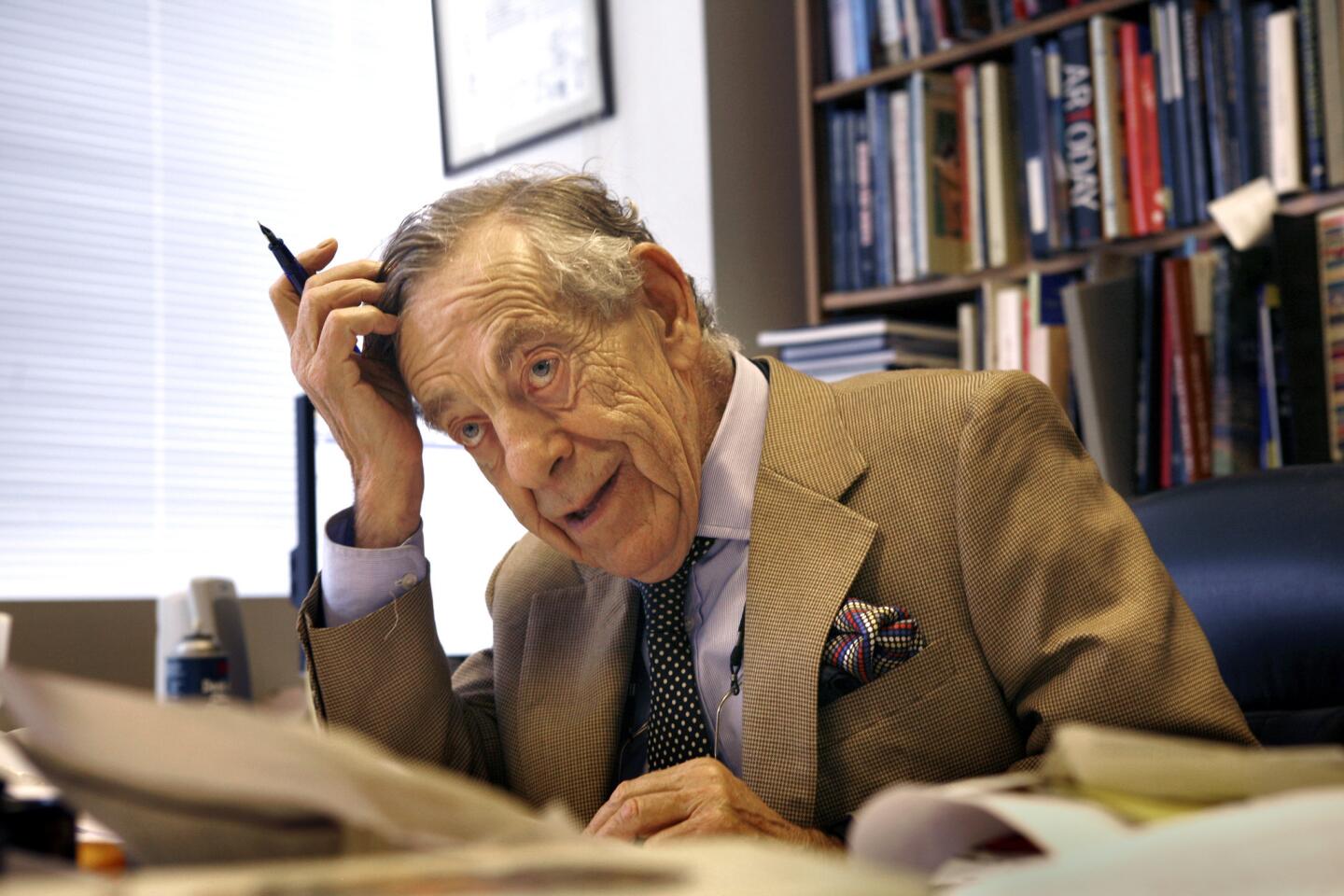

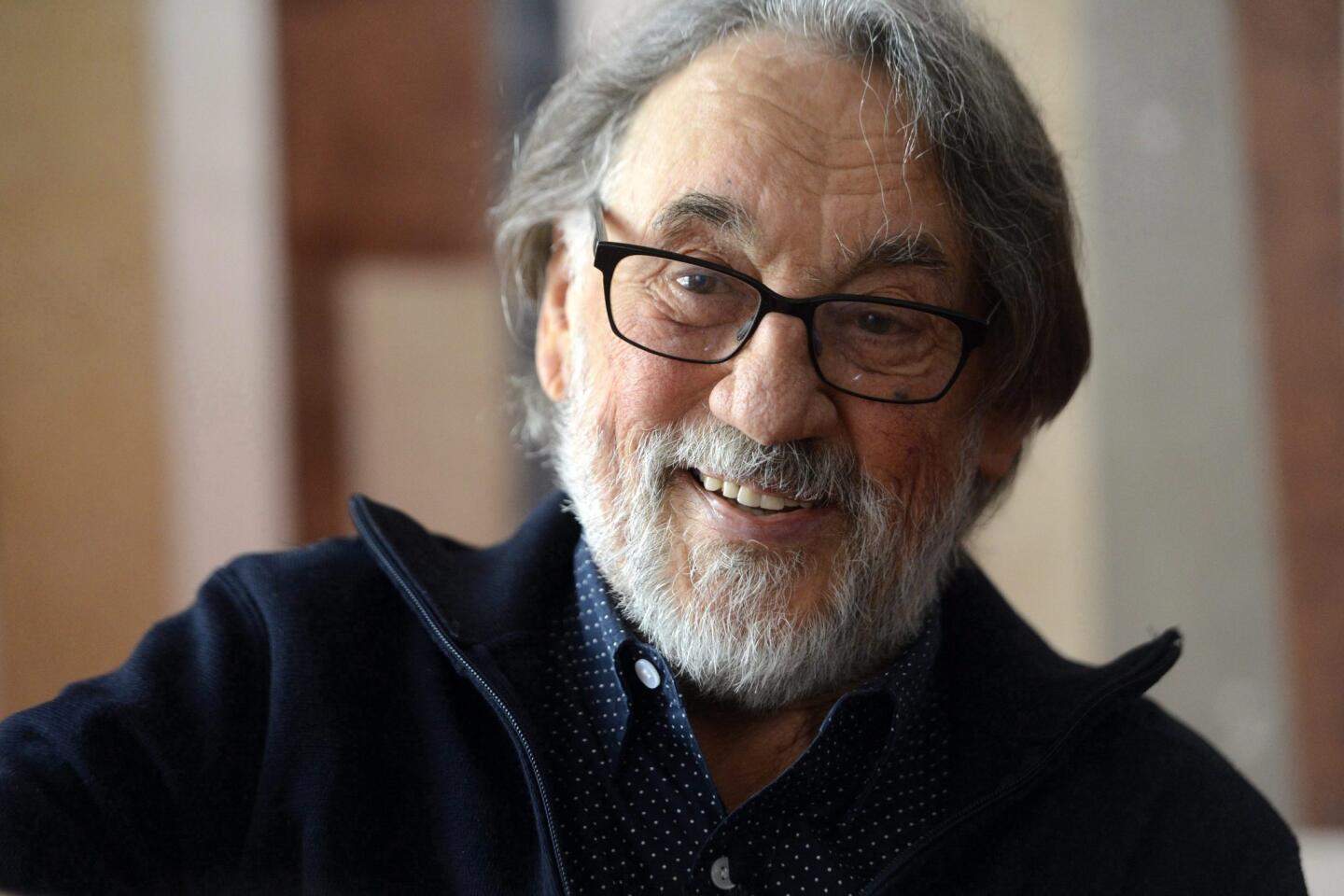

Edward Albee, three-time Pulitzer-winning playwright and ‘Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?’ author, dies at 88

Edward Albee, the award-winning playwright who instilled fire-breathing life into George and Martha, the middle-aged couple who made his “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” a clenched battleground of love-hate matrimony, has died. He was 88.

Personal assistant Jakob Holder, executive director of the Edward F. Albee Foundation, said the playwright died Friday at his home on Long Island after a short illness. Holder couldn’t provide a cause of death.

For the record:

10:40 a.m. Nov. 15, 2024An earlier version of this article misspelled Jakob Holder’s name as Jacob.

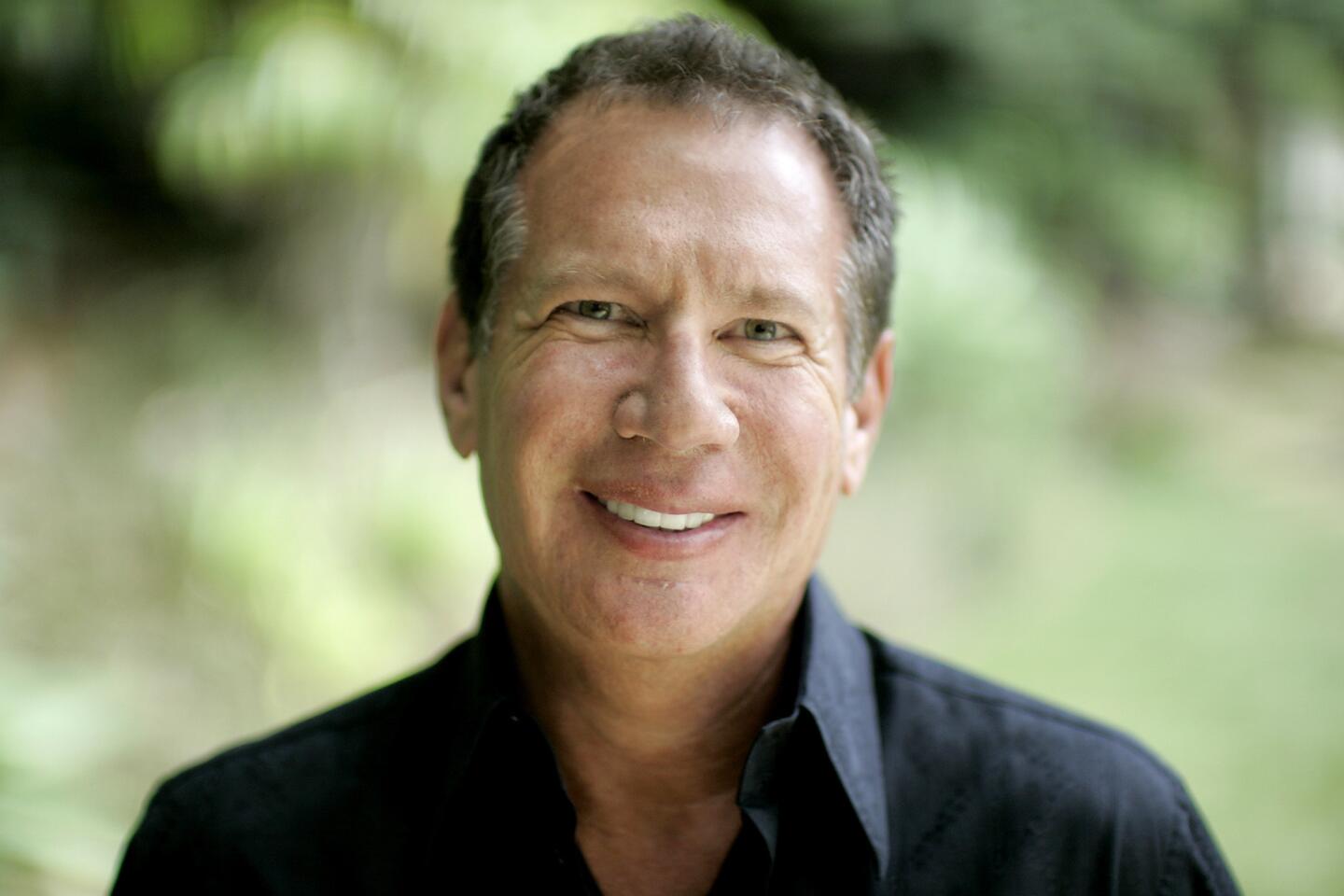

“He invented a new language — the first authentically new voice in theater since Tennessee Williams,” said playwright Terrence McNally, who lived with Albee for more than six years in the 1960s and recalled Albee’s toughness (“he was not a gusher, he didn’t ‘love’ anything”) and distinctive way with dialogue.

“He created a sound world,” McNally said Friday. “He was a sculptor of words.”

Albee influenced generations in the theater world, said Anna D. Shapiro, artistic director of Chicago’s Steppenwolf Theatre Company, whose 50th anniversary production of “Virginia Woolf” won the Tony for best revival of play in 2013.

“His work and the excellence it demanded was true north for so many of us and will continue to serve as such for decades to come,” she said by email.

INTERVIEW: Times theater critic Charles McNulty’s 2009 conversation with Edward Albee »

Albee won the Pulitzer Prize for drama three times — though not for “Virginia Woolf” — during a long, protean, sometimes experimental playwriting career. Despite his standing as one of the leading literary figures of his time, he rarely gained universal acclaim from the critics, and he was not shy about returning his detractors’ volleys. He typically wrote about the Northeastern suburban upper-crust in which he was raised, aiming to provoke audiences rather than reward them with comfortable pleasures.

“A play, at its very best, is an act of aggression against the status quo,” he told a group of aspiring teen-aged playwrights in San Diego in 1989.

From the start of his career in 1958 at 30, Albee resisted stasis in his own work, which went through frequent swerves of subject and style. From his imagination sprang some of the theater’s strangest scenarios: the undistinguished fellow who becomes a celebrity by growing an extra limb in “The Man Who Had Three Arms” (1983), and the two lizards who crawl out of the ocean in “Seascape” (1975) to converse with a couple lying on a beach and trying to sort out what to do with themselves now that they’re retired.

After Albee’s initial series of successes — “The Zoo Story,” an off-Broadway hit in 1960; “Virginia Woolf,” which ran on Broadway for 19 months in 1962-64; and “A Delicate Balance,” which won the Pulitzer in 1967 — the playwright’s critics complained that his themes became abstruse, his symbols too heavy and his language too rarefied.

For a long stretch from the late 1960s to the early 1990s, he wrote steadily and even won a Pulitzer for “Seascape” in 1975. But he was largely out of favor.

The drought ended with his third Pulitzer in 1994 for “Three Tall Women,” the play that Los Angeles Times theater critic Charles McNulty has called Albee’s masterpiece. That was followed in 1996 by an acclaimed Broadway revival of “A Delicate Balance,” the elegant but unsettling drama about the accommodations a family makes to stay together, albeit unhappily.

Even “Tiny Alice,” the 1964 play that took a radical turn toward the symbolic after the earthy “Virginia Woolf,” was appreciated anew in a late-’90s revival. During its initial run, Albee had insisted that “Tiny Alice” was perfectly intelligible so long as audiences tuned out critics who declared it impossible to understand.

“Some critics are just morons by nature,” Albee told the New York Times years later. “Others are there to save the audience from any interesting experience.”

In 2002, well into his 70s, Albee was still going for the unexpected: His play “The Goat, or, Who Is Sylvia?” concerned an acclaimed, happily married architect who throws his life into turmoil by falling into a torrid sexual affair with a goat named Sylvia.

“With any luck, there will be people standing up, shaking their fists during the performance and throwing things at the stage,” Albee told Steven Drukman in Interview magazine. “I hope so!”

“The Goat” earned Albee a best-play Tony Award, the second of his career — 39 years after “Virginia Woolf” yielded the first.

Albee (pronounced AWL-bee) was born March 12, 1928, in Washington, D.C., to Louise Harvey, who, having been deserted by the baby’s father, pursued adoption two weeks later, according to Albee biographer Mel Gussow.

Soon the infant was swaddled in luxury in Larchmont, N.Y., the son of Reed and Frances “Frankie” Albee. They named him Edward Franklin Albee III after his adoptive grandfather, who had made a fortune as the magnate of a national chain of vaudeville theaters.

It was the antithesis of a warm, nurturing home.

“Frankie was imperious, demanding and unloving,” Gussow wrote in “Edward Albee: A Singular Journey” (1999). “Reed was uncommunicative and disengaged.”

The youngster did have a household ally in his maternal grandmother, whom he portrayed sympathetically in two early plays, “Sandbox” and “The American Dream.”

Albee recalled being chauffeured to his first play as a small boy in one of the family’s two Rolls-Royces. The play was “Jumbo,” in which Jimmy Durante was followed around the stage by a live elephant.

At 6, Albee said, he knew he wanted to be a writer. But his academic career was fairly disastrous — a series of private schools that bounced him for lack of motivation, and a hellish, yearlong stint in a Pennsylvania military academy.

Albee found a niche at Choate, an elite boarding school in Connecticut, where he wrote poems and plays and attempted the first of two youthful, never-published novels. He washed out of Trinity College in Hartford after a year and a half, dismissed for failing to attend classes and chapel.

Albee moved to Larchmont but soon left for Greenwich Village, in 1949, severing ties with his family that wouldn’t be renewed for 17 years — and then, according to his interviews, without any real intimacy. His father died in 1961; Albee, who did not attend his funeral, described him as “somebody I never knew.”

In 1952, Albee, an openly gay man throughout his adulthood, moved in with composer William Flanagan. Albee worked odd jobs, the steadiest delivering telegrams. Meanwhile, he wrote without accomplishing much and found himself on the verge of 30 and, as Gussow quoted him, “fed up with everything, including myself.”

At that point, “The Zoo Story” poured out of him, written on a typewriter he had swiped from Western Union. This strange, one-act play concerned a slow-building, ultimately explosive park bench encounter in which alienated Jerry accosts placid, apparently well-adjusted Peter and refuses to be shrugged off.

More short plays followed, including “The American Dream,” one of several scripts Albee would weave from the troubled strands of his boyhood home life.

“The Zoo Story” arrived in New York in 1960, after premiering in 1959 in a German translation in West Berlin, and Albee instantly became point man for the emerging Off-Broadway theater movement marked by plays darker and grittier than the gift-wrapped affirmations typical of commercial Broadway.

John Guare, later the acclaimed playwright of “Six Degrees of Separation,” recalled in Gussow’s book that seeing “The Zoo Story” jolted him into a recognition of theater’s potential to tell visceral, hard-hitting stories.

“The future had finally shown up. Whatever theatrical revolution had started in England and France had finally hit America. Holy Christ, maybe I could be a playwright.”

Albee often said that he mulled his plays for months, sometimes for many years, without writing a word. Then he quickly set them down on paper.

One idea that lodged in his head was a literary joke he saw scrawled in soap on the mirror behind a Greenwich Village bar during the mid-1950s: “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?”

Years later, the line gave rise to a story about a broken-down college professor and his wife, clawing their way through a marriage, drunkenly inflicting their psychic gamesmanship on each other and a couple of younger houseguests, and coming to terms with their most emotionally fraught invention: the shared fantasy that they are parents of a teen-aged son.

“I think [George and Martha] love each other very much,” Albee told Kathy Sullivan in a 1984 interview published in editor Philip C. Kolin’s collection “Conversations With Edward Albee.” “They’ve had a lot of battles, but they enjoy each other’s ability to battle. I think once they’ve … gotten rid of the illusion, they might be able to build a sensible relationship.”

Arthur Hill and Uta Hagen won best actor and actress Tonys as George and Martha. And Albee said that, despite some small reservations, he was pleased with Mike Nichols’ 1966 film version, starring Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor.

“A Delicate Balance” was also made into a film — the 1973 release was directed by Tony Richardson and starred Katharine Hepburn, Paul Scofield and Lee Remick.

“Virginia Woolf” generated the first big controversy of Albee’s career: Two theater critics who composed the Pulitzer nominating jury for drama recommended it for the prize, but the Pulitzer board rejected it and awarded no prize in the category. The nomination had gotten caught up in the ferment of the early ’60s, when old standards were giving way grudgingly to a new sense of artistic license. Gussow reports that one board member branded the play “a filthy play … narrow-minded and bigoted.” The two nominating critics resigned in protest, one of them accusing the Pulitzer board of making “a farce out of the drama award.”

Albee shrugged off the lost Pulitzer, saying that awards were nice, but he never counted on winning them.

“Virginia Woolf” also spawned assertions that Albee was a misogynist because of his portrayal of the raging, foul-mouthed Martha.

“Actually, the women in my plays are stronger and more able to deal with life than the men are,” Albee countered in a 1975 PBS interview. “The only people who’ve perpetuated this fiction are people who themselves can’t accept women as being strong and vital and vocal people.”

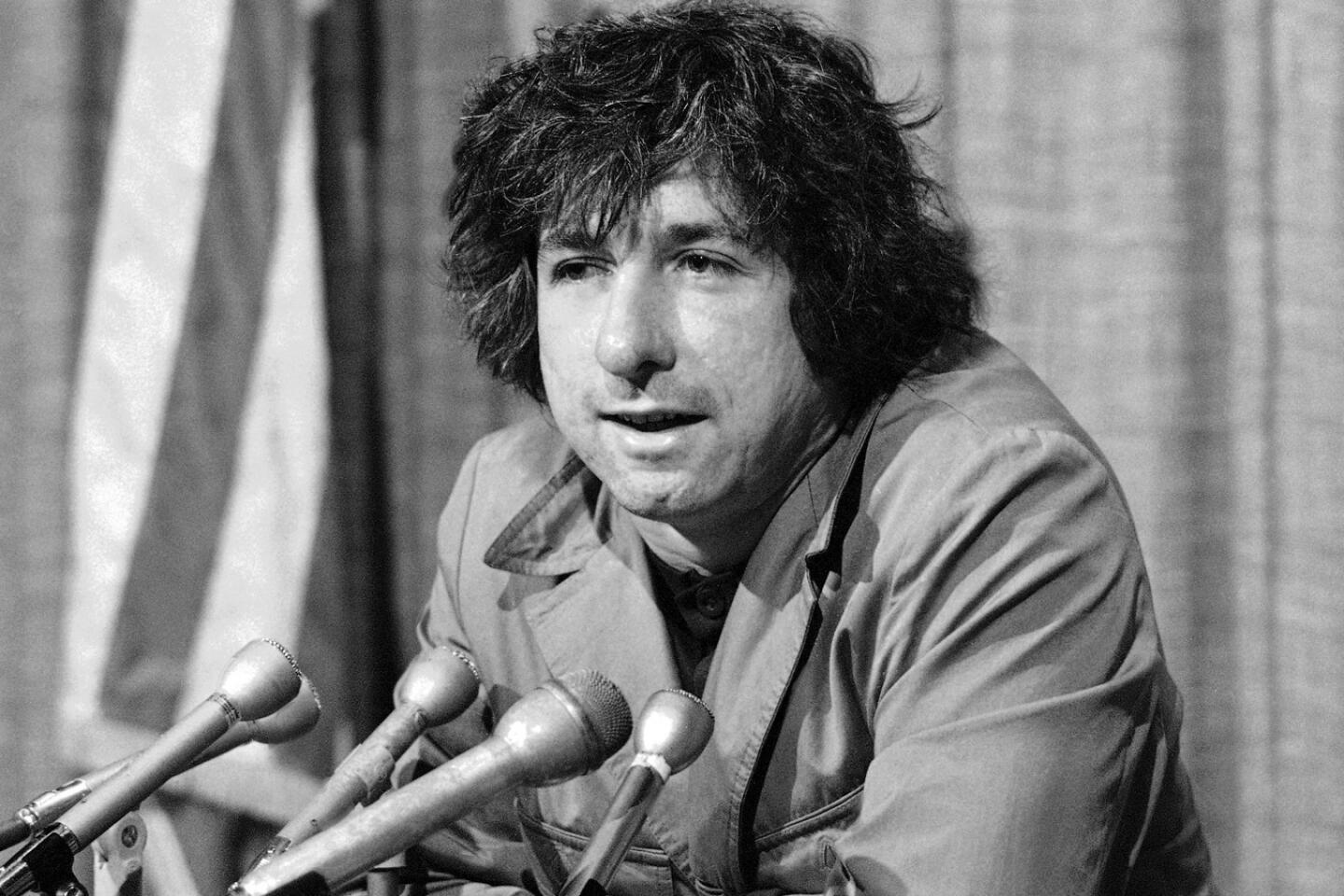

From other quarters, Albee drew fire for not addressing gay themes in his plays and for failing to take on political subjects from his perch as a leading playwright during the eras of the Vietnam War, race riots, Watergate, the Cold War and the AIDS crisis.

His interviews could be opinionated — especially against conservative politics — but he felt topical drama would soon seem dated and devoted his plays to examining the human flaws that gave rise to society’s larger ills.

“We don’t need an attack on the conscious. We need an attack on the unconscious,” he told the New York Times in 1971. “[President] Nixon and the ghettos are particular horrors that have come about because people are so closed down about themselves. …Why does everyone want to go to sleep when the only thing left is to stay awake?”

By the time he expressed this view, however, Albee’s U.S. audience indeed had largely drifted off — or at least away.

In 1971, T.E. Kalem, writing in Time magazine, said Albee seemed to have had two careers: an early one full of “great gusto, waspish humor and feral power,” then a downslide into “murky metaphysics and experimental blind alleys.”

Heavy drinking during the late 1960s and 1970s may have hampered his artistry. Albee, who was diagnosed as a diabetic in middle age, credited his partner Jonathan Thomas with helping him give up alcohol — and the churlish behavior that often came with his drinking bouts.

The 1980s brought more failures. Frank Rich in the New York Times dismissed “The Man Who Had Three Arms” as “a temper tantrum in two acts,” viewing its central character, a has-been celebrity, as “a maudlin stand-in” for Albee himself. Albee’s response was typically tart: If the character had been a reflection of himself, he said, he would have given him talent rather than rendering him as an extra-appendaged freak.

Albee claimed not to be daunted by contemptuous reviews, convinced that a play’s reception had nothing to do with its quality.

“If you know that, you can never be owned by public opinion or critical response,” he told the New York Times in 1994. “You just have to make the assumption you’re doing good work and go on doing it. Of course, there are the little dolls you stick pins in privately.”

The 1990s brought new success and a re-evaluation of older works. After Frankie Albee’s death in 1989, Albee wrote “Three Tall Women,” which premiered in Vienna in 1991 — the Europeans, who had had the first glimpse of “The Zoo Story,” had never stopped holding him in high esteem. Three actresses, identified only as A, B and C, represented Albee’s mother at different stages of her life: young, middle-aged and near death. He said that writing it didn’t make him feel closer to his mother, but it did help him understand her better.

The play won him his third Pulitzer in 1994, and Benedict Nightingale, in the Times of London, hailed it as “a living reproach to those of us who had written off the author as a burnt-out volcano, a dramatist 30 years past his prime.”

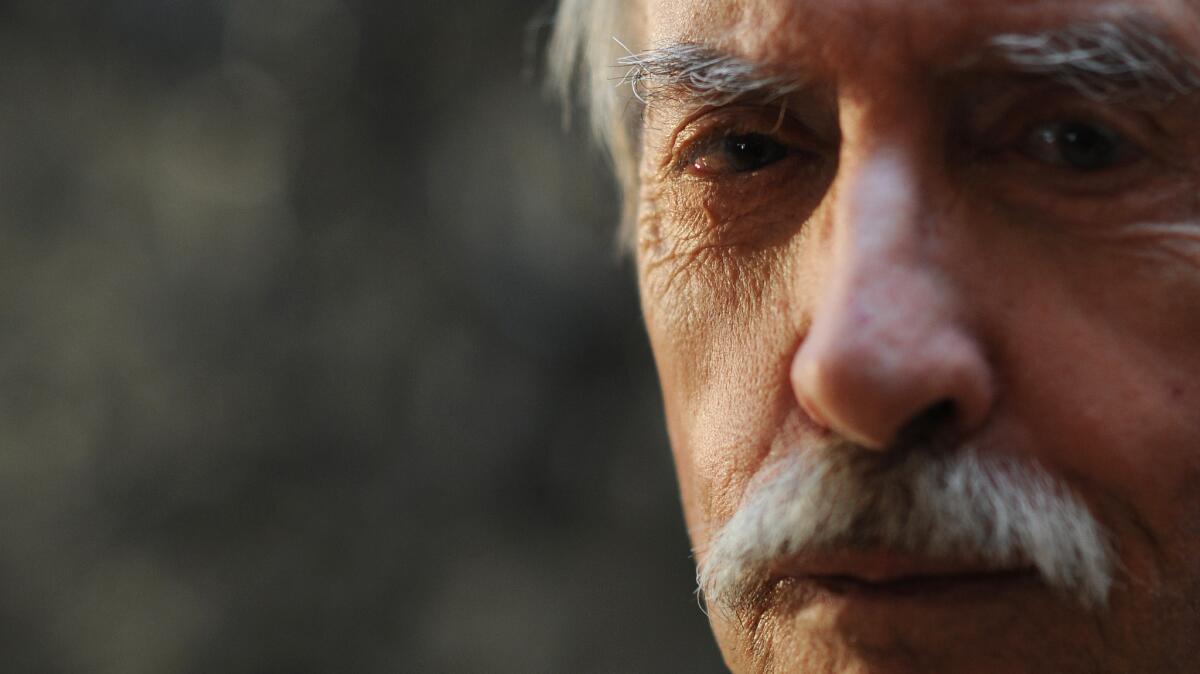

Albee said he considered writing a form of enjoyment. His other passions included a large collection of modern art; cooking, and riding roller coasters — something he said he took up to help conquer a fear of flying.

He surrounded himself with numerous dogs and cats, and among the most memorable speeches in his plays are two unsentimental looks at the relations between humans and critters: Jerry’s epic monologue in “The Zoo Story” about how his hatred for his landlady’s dog, “a black monster of a beast,” turned to sad, mutual indifference, and Tobias’ recollection in “A Delicate Balance” about how his once-affectionate pet cat grew unaccountably alienated from him — with dire consequences for the cat.

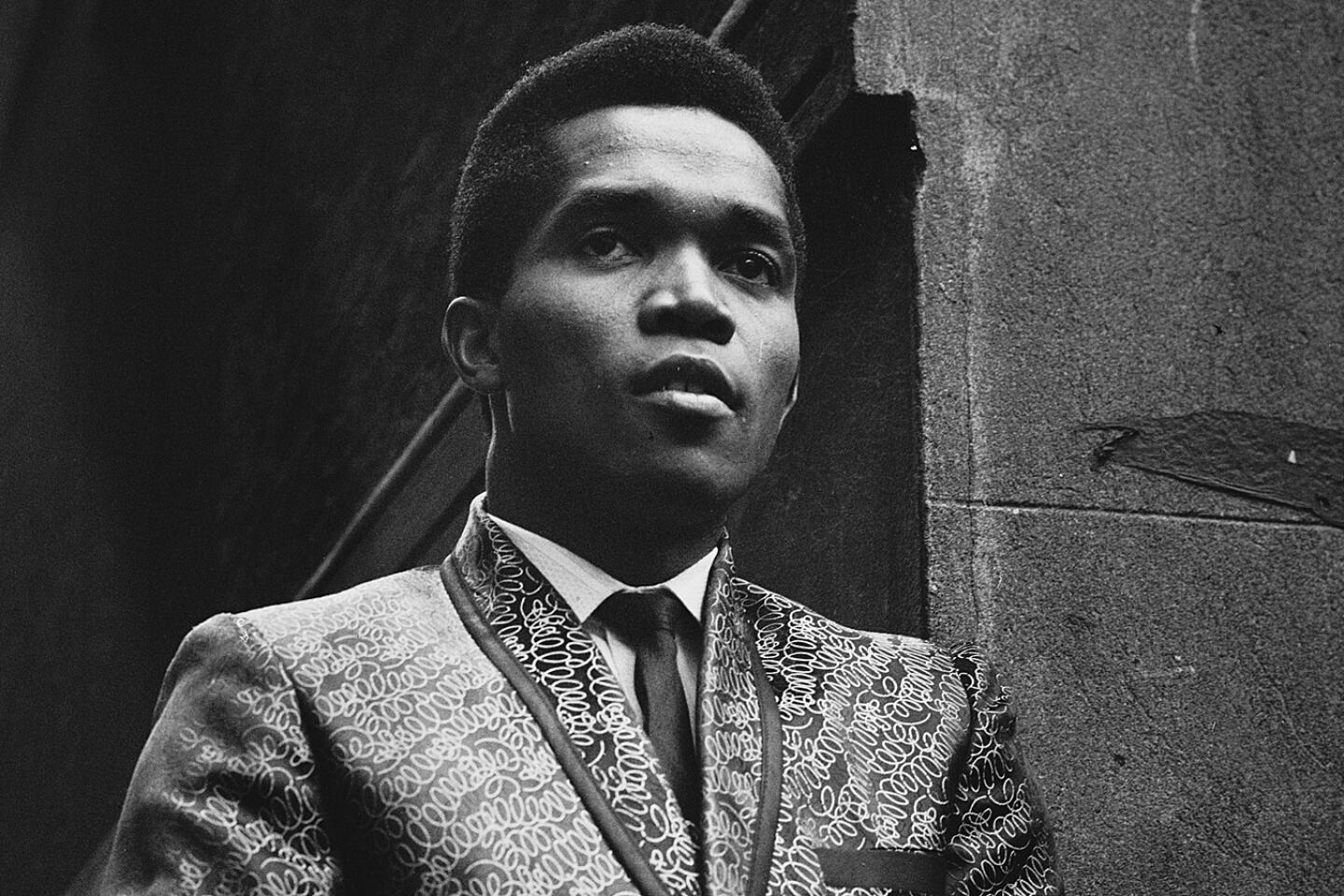

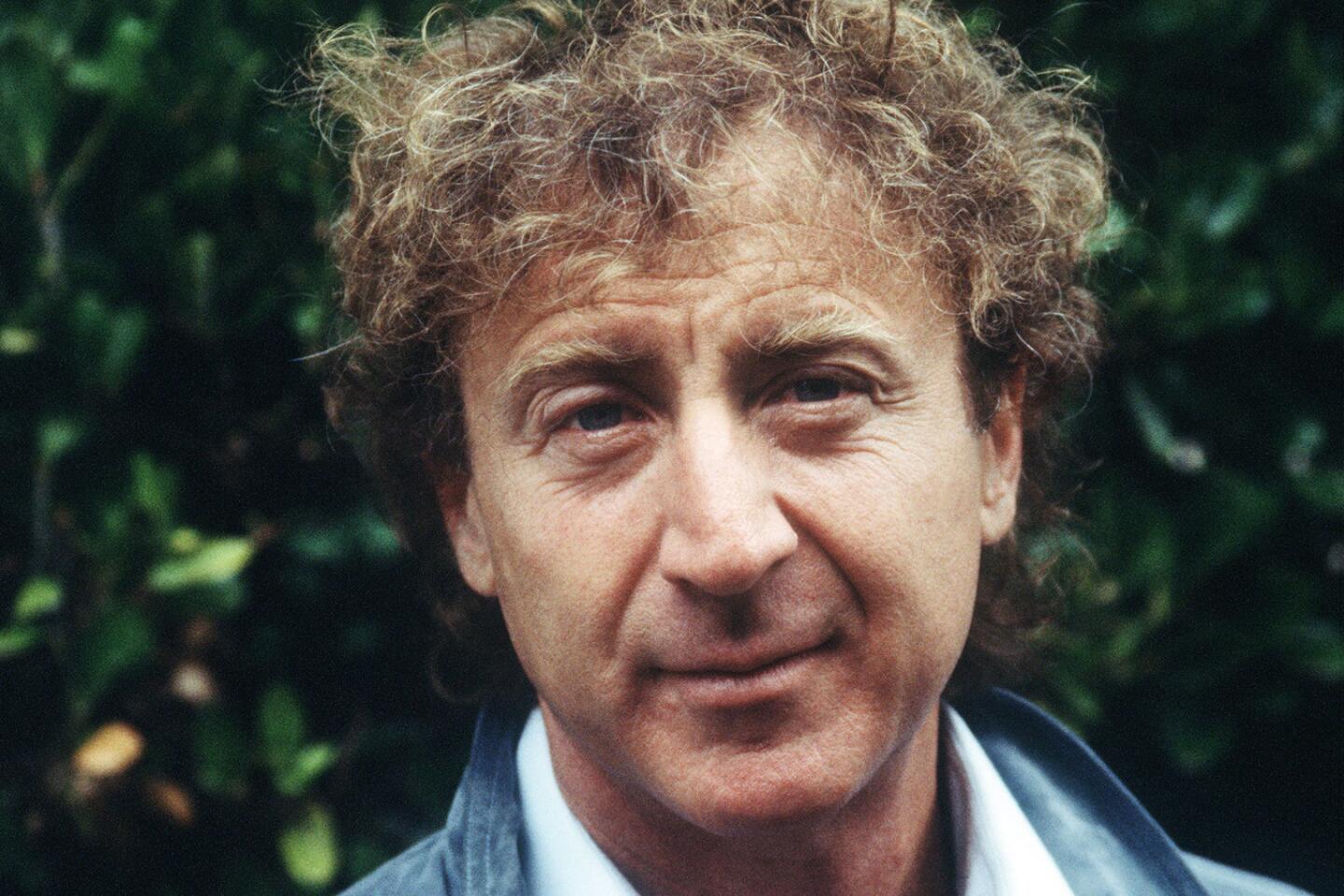

Albee used part of his windfall from “Virginia Woolf” to launch the Playwrights Unit with the play’s producers, Richard Barr and Clinton Wilder. For about a decade it fostered emerging playwrights by underwriting readings and workshop productions of their scripts; among the future eminences Albee’s entity helped were Sam Shepard, Lanford Wilson, Amiri Baraka (LeRoi Jones), Guare and McNally.

Later, Albee started a foundation named for himself that sponsors working retreats and communal living for artists in various disciplines at his property in Montauk, Long Island. Albee frequently lectured and taught playwriting, including a long-term visiting professorship at the University of Houston.

In April 1998, shortly after his 70th birthday, Albee came to Hollywood to give one of his many talks. He descended to the basement of an office building where the Eagles Center, a public school for at-risk gay teens, was quartered.

“Too many people get constricted by social norms, miss out by not living a full life,” he told the students gathered there. “The important thing is to be yourself absolutely. When I die, I would like to realize I haven’t missed out on too much.”

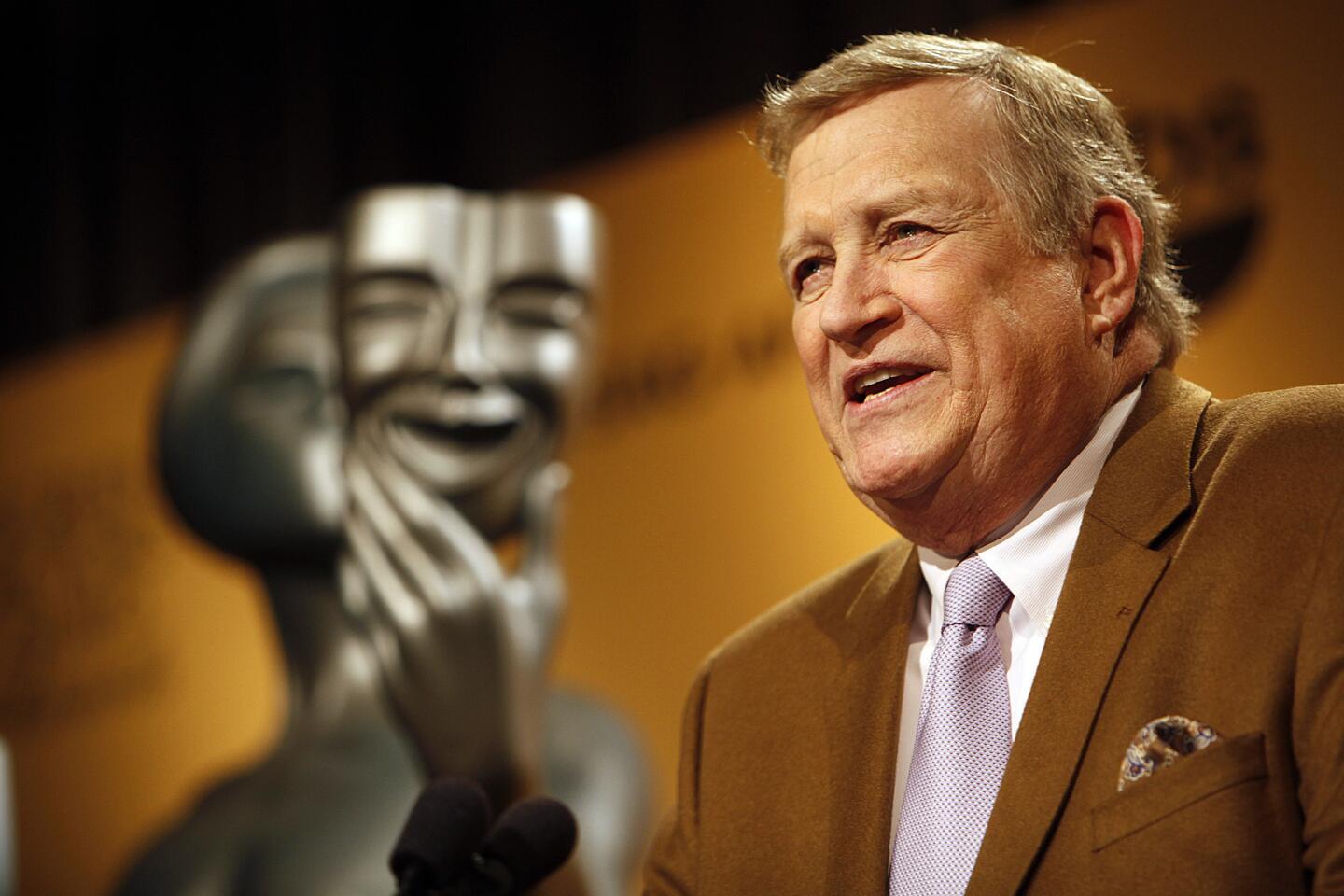

Thomas, Albee’s partner since 1971, died of cancer in May 2005. A month later, Albee accepted a lifetime achievement Tony Award.

At the Signature Theatre in New York, Albee’s late career got an influential push from founding artistic director Jim Houghton, who died this summer of cancer at 57. Executive Director Erika Mallin said Friday by email that in Houghton’s last season at the Signature helm, “he chose to produce ‘The Sandbox’ in deference to his great friend Edward and to bring to new audiences this seminal play that helped to launch the off-Broadway movement.”

McNally saw Albee two weeks ago on Long Island and “he was in good spirits,” McNally said. “He died in Montauk listening to the sea, which I think was his favorite sound.”

Times staff writers David Ng and Craig Nakano contributed to this report.

MORE OBITUARIES

Frank Wyle, aerospace innovator and L.A. museum benefactor, dies at 97

Greta Friedman, woman in iconic WWII Times Square kiss photograph, dies at 92

Transgender performer Lady Chablis dies at 59; portrayed in best-selling book

UPDATES:

Sept. 17, 8:45 a.m.: This article has been updated with additional background and reaction.

This article was originally published at 6:05 p.m., Sept. 16.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.