Willie Williams, Los Angeles police chief after the 1992 riots, dies at age 72

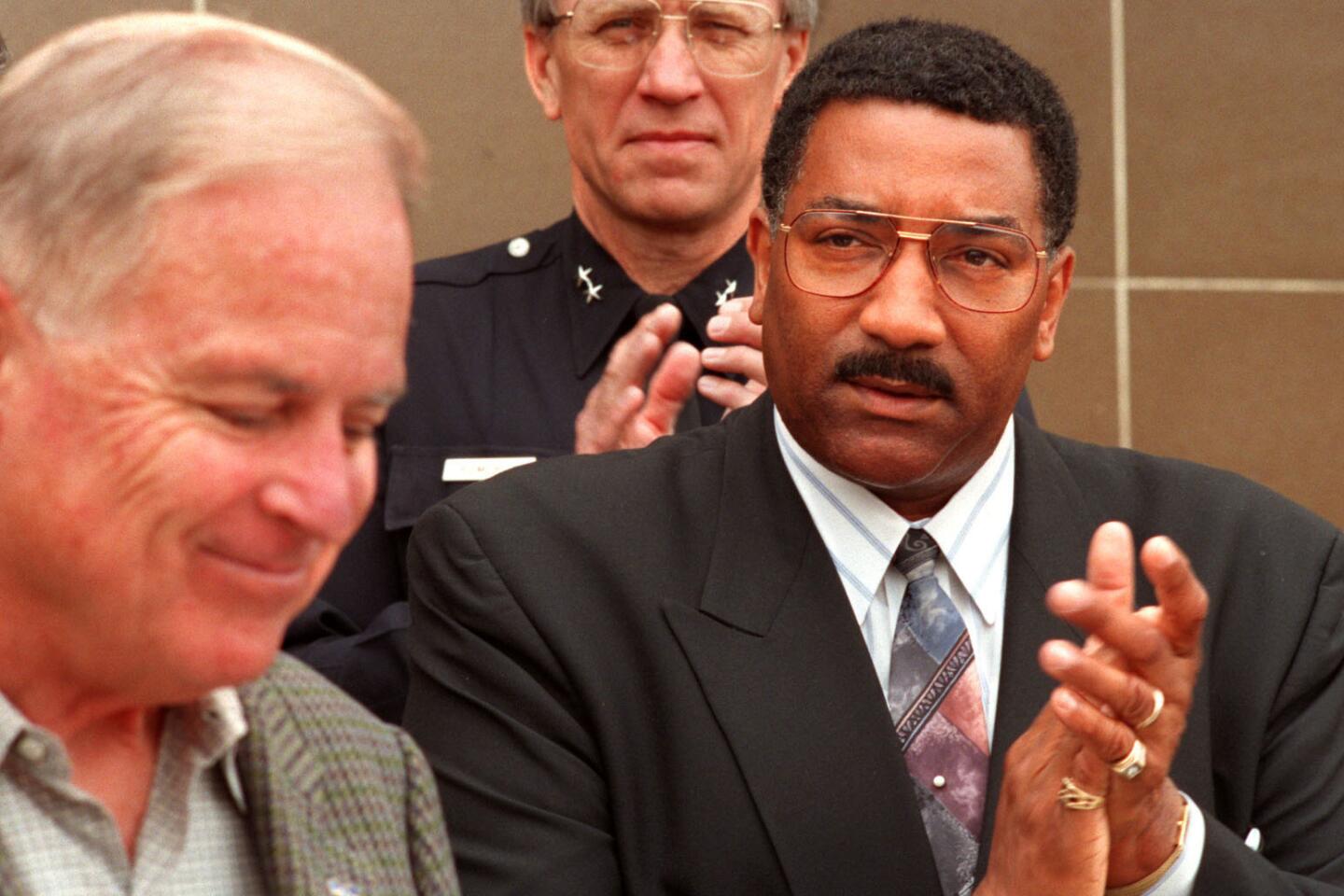

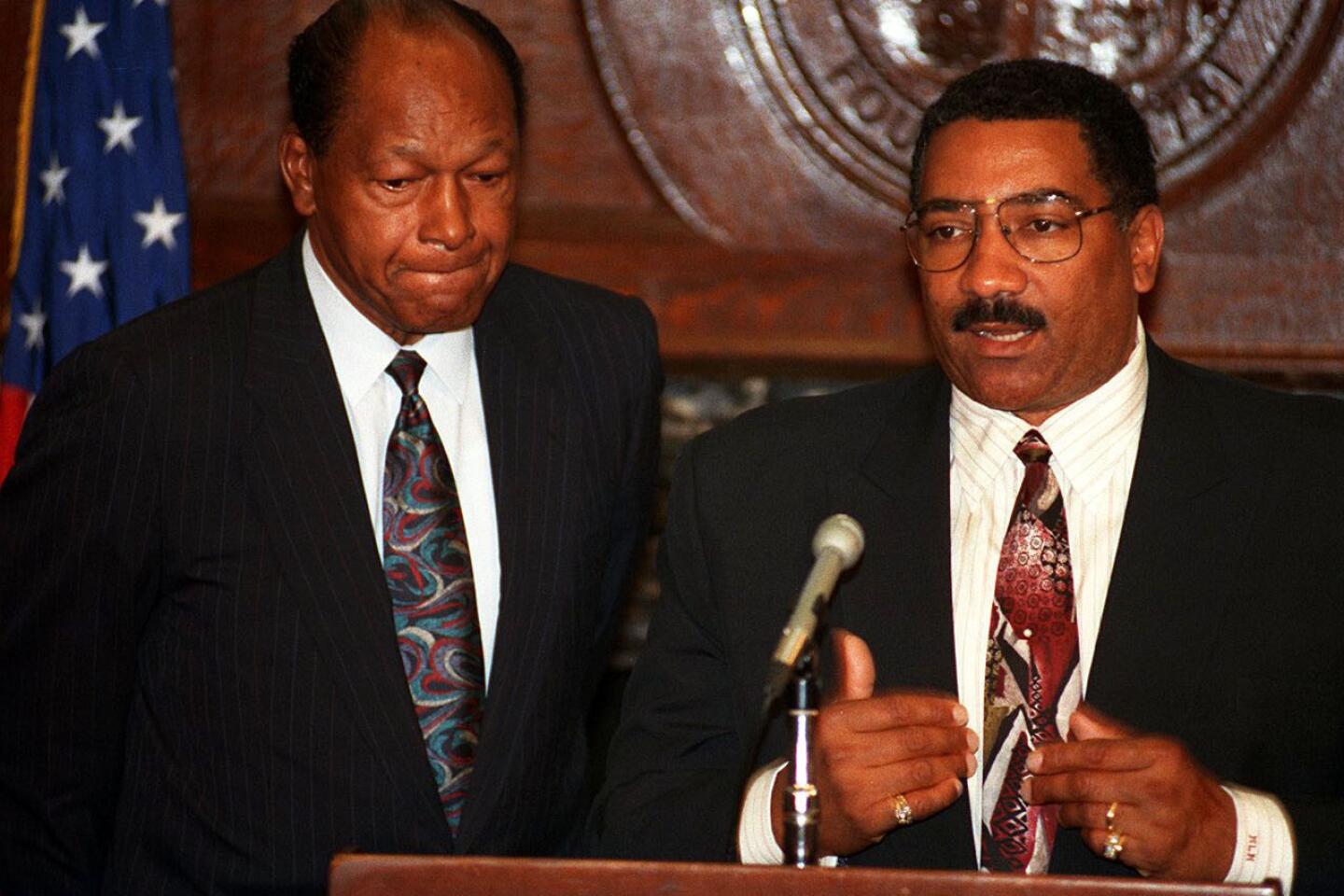

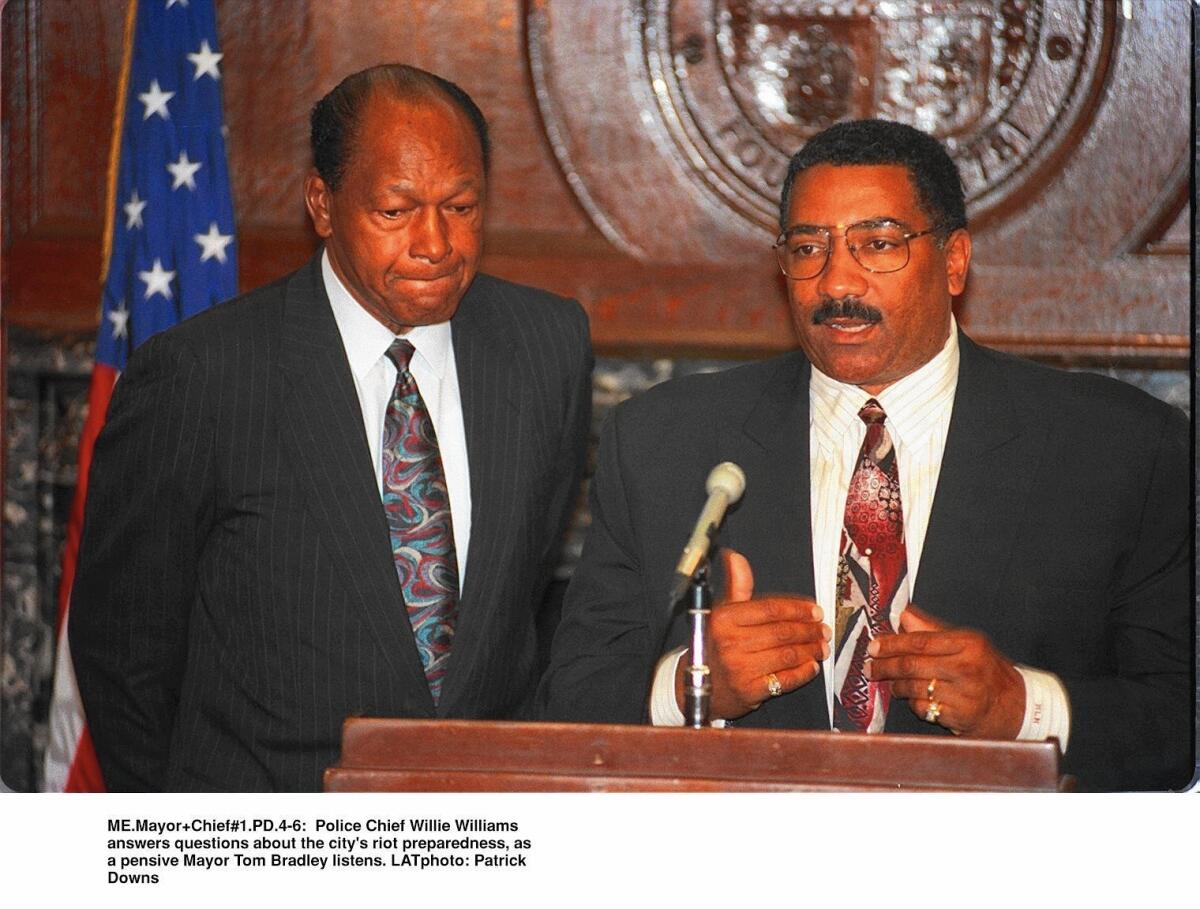

Willie Williams, right, who had headed the Philadelphia Police Department, was named LAPD chief by Mayor Tom Bradley after the 1992 riots.

Willie L. Williams, the first African American chief of the Los Angeles Police Department, who steadied the agency in the tumultuous wake of the 1992 riots but was distrusted as an outsider by many officers and politicians, has died. He was 72.

Williams died after a long struggle with pancreatic cancer, his wife, Evelina, said in a brief phone interview. The couple lived in Fayetteville, Ga., outside Atlanta.

The son of a butcher, Williams spent a career rising to the top ranks of the Philadelphia Police Department before he stepped into the top job at the LAPD in 1992. It was a sensitive time, as the department was reeling from its poor handling of the riots that erupted after the acquittal of officers who beat Rodney G. King during a violent arrest and as the city at large struggled to mend deep racial divides.

The challenge facing Williams was all the more daunting given his predecessor, Daryl F. Gates, a deeply polarizing figure who had won fierce loyalty from rank-and-file officers but had long been criticized as running the LAPD like a brutish, occupying quasi-military force that mistreated blacks and other minorities.

“Willie Williams was appointed to do some healing, and in many ways he succeeded, building and rebuilding positive, constructive relationships between the African American community and the police,” said John Mack, a longtime civil rights leader who served on the city’s civilian Police Commission. “But the deck was stacked against him from the start. The Los Angeles Police Department was not ready to accept him for two reasons: He was an outsider and he was African American.”

Chosen by then-Mayor Tom Bradley to replace Gates over several high-ranking LAPD officials, Williams arrived promising to follow the same blueprint he had used to run the Philadelphia department. At the heart of the plan was his belief in community policing, a relatively novel idea at the time that emphasized the need for police to integrate themselves closely into the communities they serve in order to build trust.

It was a message that resonated with residents, as polls showed Williams enjoyed strong approval ratings among residents throughout the city. City officials praised him for stabilizing the department and repairing its reputation.

See the most-read stories this hour >>

Williams showed a willingness to fight for changes. He pushed for increased hiring of female officers and spoke out about the need to address rampant sexual harassment and discrimination within the ranks. He increased the size of the department and advocated for reforms drawn up in 1991 by the Christopher Commission, which had been formed by Bradley after the King beating to review LAPD training, discipline and complaint systems.

But doubts and resistance to Williams’ leadership soon took root. Within a year of Williams’ taking over the department, Bradley had been replaced as mayor by Richard Riordan. With his staunchest political protector gone, the chief found himself increasingly alienated in the city’s power circles as police union officials and rank-and-file cops grew increasingly hostile to his leadership, and his management skills came under scrutiny.

In 1995, a letter from a former LAPD official to the Police Commission led to an investigation into allegations that Williams had accepted free accommodations from a Las Vegas casino.

Williams vigorously denied the claim, saying it was part of an orchestrated smear campaign. The commission, however, uncovered receipts showing that Williams and his family had accepted free rooms on several occasions.

Williams said the rooms had been provided in exchange for the gambling he and his family had done, but the commission concluded he had lied. The panel voted to reprimand him — a move that led to a political power struggle as Riordan upheld the sanction, only to see it overturned by the City Council.

Williams survived the mini-scandal, but never fully recovered from it. His approval ratings sank as he increasingly pitted himself against Riordan and the city government in general. His decision to file a $10-million invasion-of-privacy claim over the hotel brouhaha was widely criticized.

He nonetheless made a bid for a second five-year term as chief in 1997, touting what he and supporters said had been his impressive leadership at a time when crime rates fell, but so did markers of productivity such as arrests.

The Police Commission, whose members were largely appointed by Riordan, chose not to give him a second term, setting the stage for Williams to be replaced by Bernard C. Parks, an African American and LAPD insider who had clashed with Williams.

In an interview with The Times as he prepared to depart the LAPD, Williams spoke with evident anger about his struggles to earn the trust and respect of officers and elected officials alike.

“In a sense, I was the guinea pig,” Williams said, adding that he believed his successor would find it easier going because of the steps he’d already taken. “It’s always nice when you can follow the trailblazer.”

Twitter: @joelrubin

Times staff writer Richard Winton contributed to this report.

ALSO

County officials look to parcel tax to help L.A.’s park-poor communities

Former San Francisco police lieutenant charged with impeding rape investigation

Top L.A. County sheriff’s official sent emails mocking Muslims, blacks, Latinos and women

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.