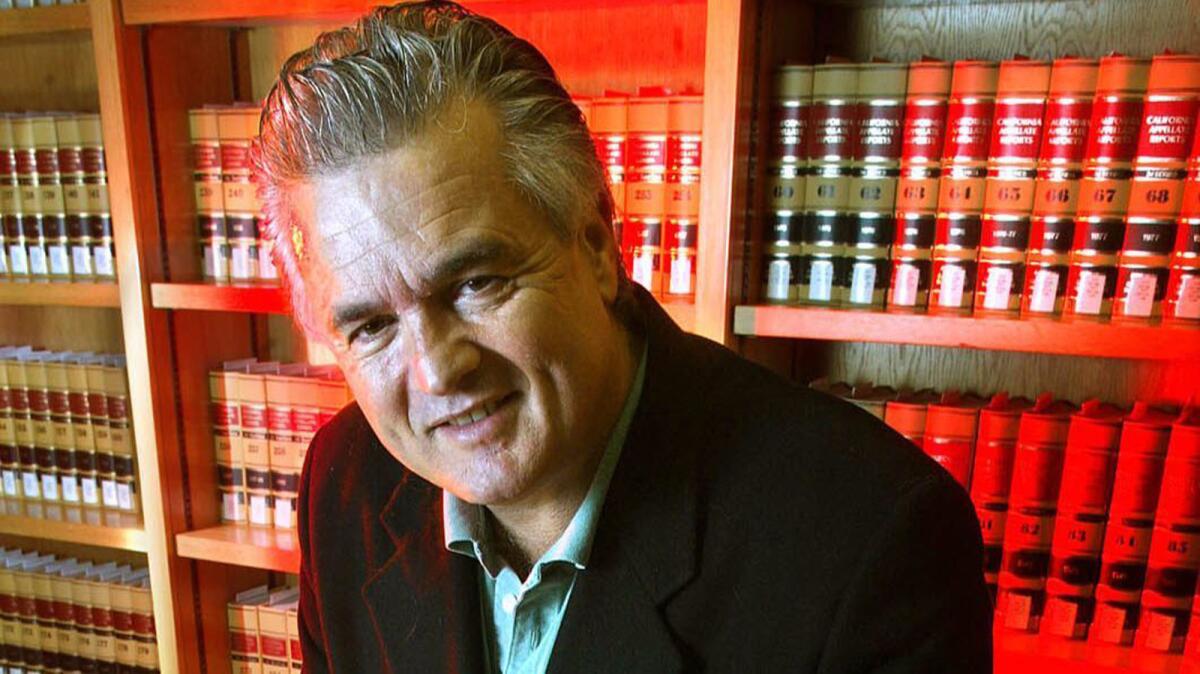

Prominent lawyer Tony Brooklier, son of powerful L.A. Mafia boss, dead at 70

Anthony Brooklier, a prominent Los Angeles attorney who went from defending his father, a powerful mob boss, to representing celebrities, corrupt businessmen, drug kingpins and the Hollywood Madam Heidi Fleiss, died Tuesday. He was 70.

Brooklier died of suicide at his Century City residence, according to the Los Angeles County coroner’s office.

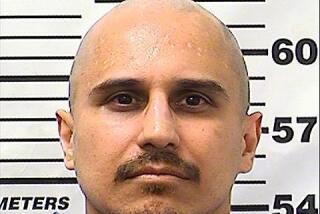

His death stunned the Southern California legal community, with lawyers, prosecutors and court staff sharing tributes of the seasoned litigator. It came about one year after Brooklier’s son, also named Anthony Brooklier, killed himself in San Bernardino County, authorities confirmed. Both died of hanging.

Donald B. Marks, Brooklier’s law partner of about 40 years, declined to discuss the circumstances of his death but acknowledged that Brooklier had been pained by the loss of his son.

“It had a very substantial impact on him,” Marks said in a telephone interview. “It was very hard for him to cope.”

As a young lawyer, Brooklier drew attention when he left his post as a deputy state attorney general to represent his father, Mafia boss Dominic Brooklier, who eventually faced two federal racketeering indictments as part of a massive crackdown on organized crime.

In the second case, the elder Brooklier was convicted of racketeering and extortion, but he and other reputed mobsters were acquitted of the 1977 murder of underworld informant Frank “The Bomp” Bompensiero.

At the 1981 sentencing before U.S. District Judge Terry J. Hatter Jr., Brooklier made an emotional plea on his father’s behalf.

“There are things in his past he shouldn’t be proud of, and I’m not proud of,” Brooklier said, later sobbing in open court. “But he’s always provided for his family. Whatever sentence he does, he’ll be missed every day.”

The elder Brooklier died behind bars, but his son’s impassioned, well-prepared defense helped establish his reputation as an attorney of choice for those facing prosecution.

He met Marks while defending organized crime figures in the 1970s, and they founded the Century City firm Marks & Brooklier, which remains a highly respected criminal defense firm.

The duo took on a range of high-profile cases. Brooklier — a tall man with well-coiffed hair — melded a polished, charming manner with aggressive advocacy.

“He had a very effective way of communicating with jurors, witnesses and judges,” Marks said. “It was quite understated, but it was based on preparation and skill.”

Brooklier represented national Hells Angels leader George Christie Jr. when he was charged with running a gang that snagged drugs from the U.S. Air Force, and fashion designer Anand Jon, who was convicted of sexually assaulting seven girls and young women.

During the attempted murder trial of Timothy McDonald, an associate of rapper Marion “Suge” Knight, Brooklier accused a Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputy of lying on the witness stand. Jurors deadlocked in deliberations and the judge eventually declared a mistrial.

Brooklier negotiated a plea deal that kept McDonald out of jail, and he later remarked to The Times: “Trials are always risky. The potential loss here was devastating — it’s life in prison versus take a plea deal and go home today.”

While defending Fleiss, who admitted to running a prostitution ring for the rich and famous, Brooklier urged the court to compare the gravity of the charge to other, more serious crimes.

“Your Honor, no one was hurt in this case, no one was coerced, and no one operated under duress,” Brooklier said. All Fleiss did, he argued, was arrange for “consensual sex between consenting adults.”

Brooklier found himself on the other side of the law in 1998, when he pleaded guilty to failing to file federal income tax returns.

The offenses were misdemeanors and the judge opted not to send him to prison. The California State Bar allowed him to keep his law license after a six-month suspension.

In more recent years, he defended a businessman caught trying to hire someone to kill his wife and a Calabasas man who was convicted of murdering an El Camino Real High School student.

“It didn’t matter who our client was,” Marks said. “We did everything we could within our function as criminal defense attorneys.”

Anthony Phillip Brooklier was born April 7, 1946, in Lynwood and grew up in Orange County. After school, Brooklier washed cars at his father’s used-car dealership in Maywood.

As a child, he said he recognized that his father, who eventually became the Godfather for all of Southern California, wasn’t like other people’s fathers.

“My father could walk into a place, and for whatever reason, the room would stop,” Brooklier told The Times in 1989. “It was as if every eye was on him.”

He graduated from Savanna High School in Anaheim in 1964 and got a congressional appointment to the U.S. Naval Academy. But during his first year, his father was listed in a national report on Mafia activities as a ranking member of the mob in L.A.

A commander summoned Brooklier and informed him that he would probably not have a successful career in the military.

Brooklier completed his undergraduate studies in 1968 at Loyola Marymount University. He earned his law degree in 1971 from UCLA after resolving to pursue a career that would defend his family.

“I wanted to put myself in a position to help my father,” he told The Times. “Because I sensed when I was a kid what was going to happen. It’s a thing all kids live with, you know — your parents will get divorced, they’ll get hurt, they’ll die. But that wasn’t my fear…. I was so taken about what my father told me happened to him when he was a kid [in prison], I was so emotional about that, that I ... was never going to let it happen again.”

Brooklier is survived by his wife, television journalist Pat LaLama, and several adult children.

Twitter: @MattHjourno.

UPDATES:

7:50 p.m. Nov. 16: This article was updated with cause of death, additional details and quotes.

This article was originally published at 7:50 p.m. Nov. 15.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.