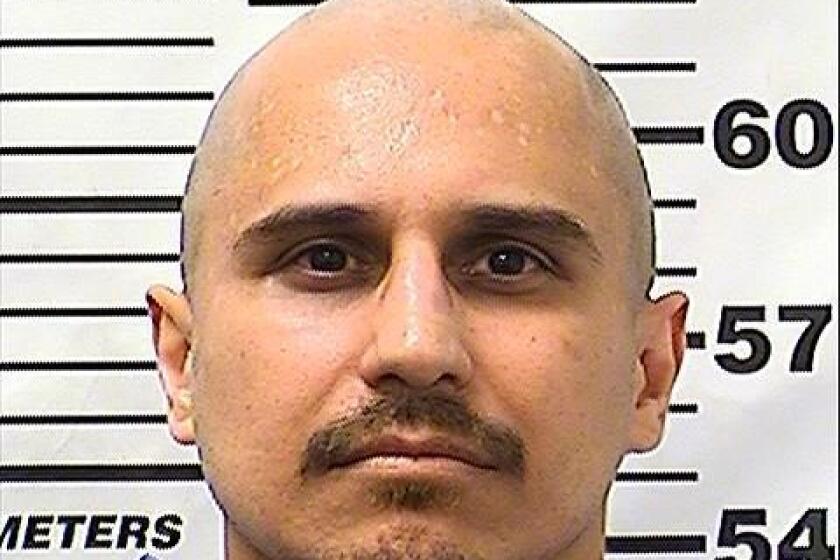

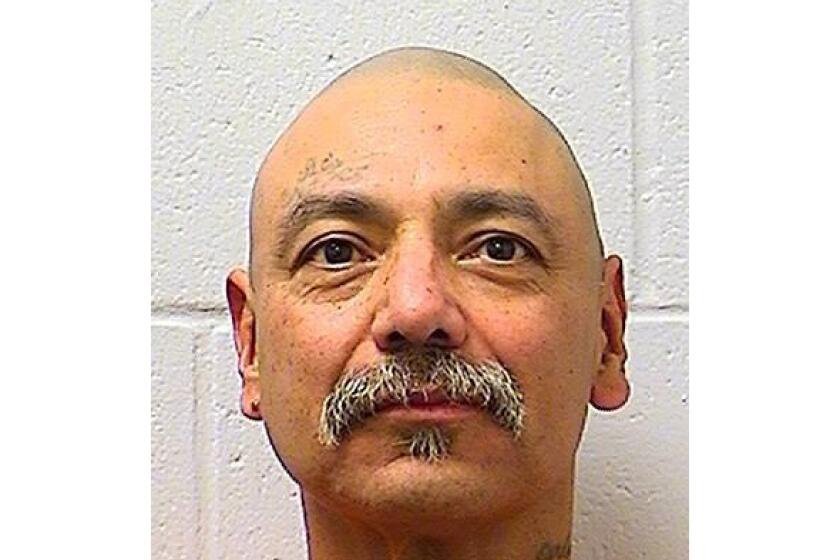

Reputed godfather of the Orange County underworld says he’s victim of ‘character assassination’

Johnny Martinez wants you to know he is not a monster.

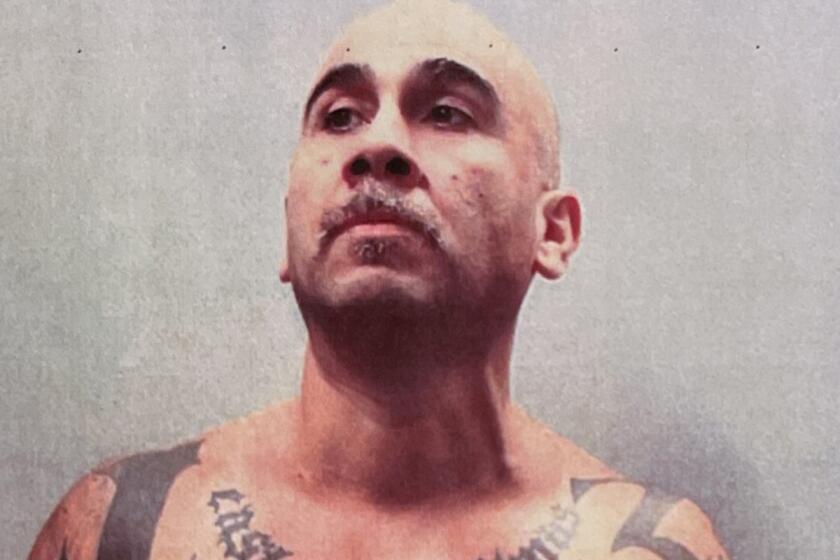

He has been called many things in the last six years by law enforcement agencies: Godfather of the Orange County underworld. Member of the Mexican Mafia, a syndicate of imprisoned Latino gang members. Architect of murders, shootings, knifings, shakedowns and drug deals.

Martinez says none of this is true. In a jailhouse interview, he told The Times that, despite the government’s best efforts to make him “sound like Hannibal Lecter,” he is an innocent man being railroaded by lying witnesses and vindictive prosecutors.

Martinez has pleaded not guilty to charges of racketeering, murder in aid of racketeering, using a firearm in a crime of violence and conspiring to distribute methamphetamine and heroin.

Prosecutors say Johnny Martinez was caught on a wiretap boasting of several murders, but he still has prominent voices calling for his release, including two L.A. County probation officials.

Prosecutors say Martinez, nicknamed “Crow,” is the Mexican Mafia’s main man in Orange County, drawing a “tax” from dozens of street gangs and a percentage from all illicit business — drugs, gambling, unlicensed marijuana dispensaries — within his territory.

But where prosecutors allege a murderous enterprise they say is proved by wiretapped calls, text messages, jailhouse notes and testimony, Martinez sees a conspiracy among law enforcement. Stung by his victories in Superior Court, Martinez claimed, local cops colluded with federal prosecutors to repackage a case he had already beaten into a federal racketeering indictment.

To hear Martinez tell it, the conspiracy is broad: the FBI, the U.S. attorney, the Orange County Sheriff’s Department and district attorney, all channeling their hopes of imprisoning him through Martinez’s former cellmate, Omar Mejia.

Representatives for the U.S. attorney, the Orange County district attorney and the FBI declined to comment. A spokeswoman for the sheriff said the department investigated all cases involving Martinez fairly and without consideration for his advocacy within the jail system. The department is “committed to ensuring all inmates’ rights are protected during investigations,” she said.

Authorities arrested a suspect last week in the death of Eduardo “Eddie Boy” Castro, a Mexican Mafia member who was gunned down five years ago while riding a bicycle in Boyle Heights.

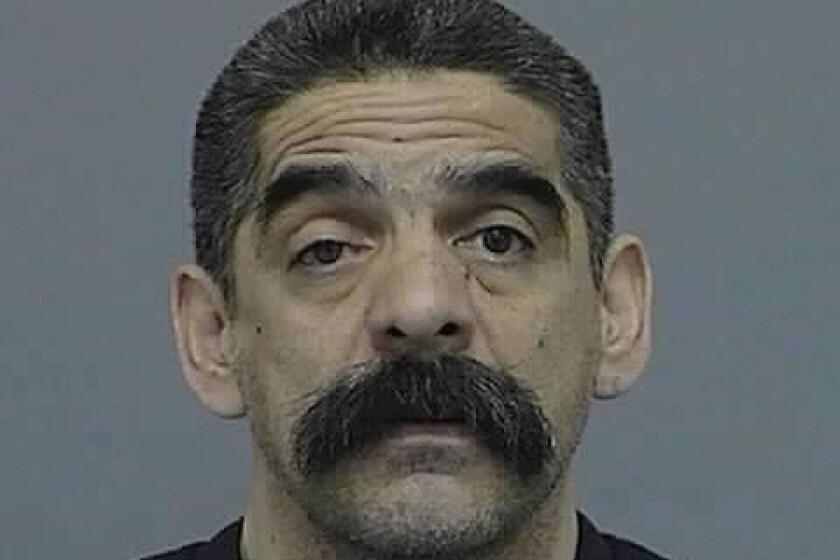

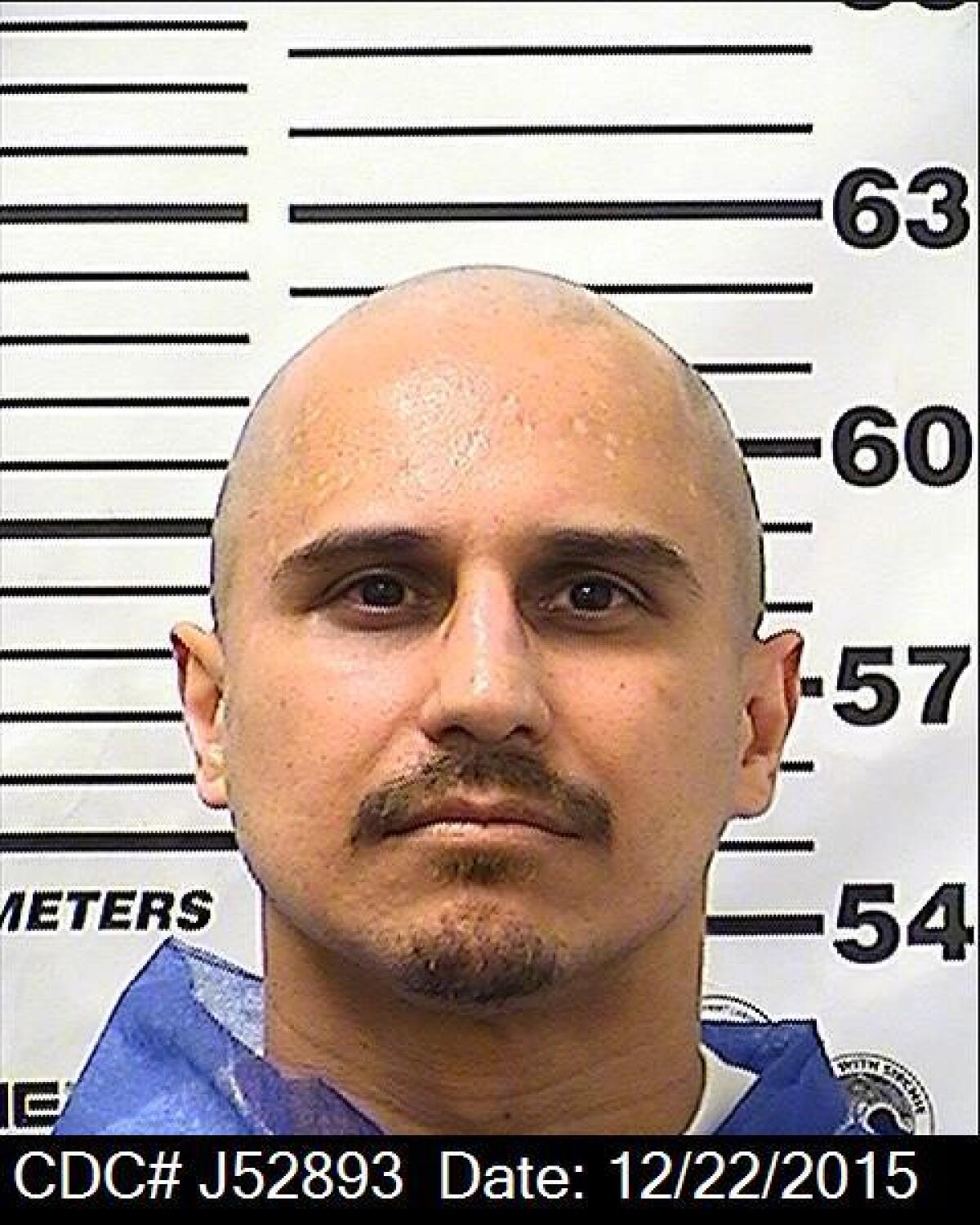

Mejia, who was indicted alongside Martinez, has testified in two federal trials that he had people shot, stabbed, beaten and extorted on Martinez’s orders.

Martinez called Mejia a shameless perjurer who became a government witness only after reviewing the evidence against him and realizing he was caught dead to rights for his own crimes. Mejia’s only way out of spending the rest of his life in prison, Martinez alleged, was to point the finger at him.

“It sends the message, in my opinion, that when you get caught doing something horrible, run to [the government] and say, ‘He told me to do it,’” Martinez said. “And they’ll welcome you with open arms.”

Martinez, 48, has spent two-thirds of his life locked up.

Arrested at 18 on suspicion of killing a man during a brawl, the Placentia native was convicted of murder under the theory that the man’s death was a “natural and probable consequence” of Martinez joining the fight. He was sentenced to 26 years to life in prison.

Law enforcement officials testified that Martinez was inducted into the Mexican Mafia around 2015. Asked by a Times reporter if this was true, Martinez said prison officials have classified him as a Mexican Mafia member, “and that’s about all I can say on that.”

A defense attorney was charged in a federal indictment with conspiring to murder a Mexican Mafia member who had fallen out of favor with the prison-based syndicate.

In an interview last week at the Santa Ana city jail, Martinez, who wore a tan jumpsuit, glasses, handcuffs and a broad smile, was unfailingly polite. After greeting a reporter with a fist bump through the glass partition, Martinez joked that the prosecutors who monitored his conversations over closed-circuit telephone must be wondering, “Why’s this guy visiting this short SOB?”

Martinez said he was speaking out against the advice of his lawyers because he needed to defend himself against a “character assassination.”

Last month, Martinez’s attorneys asked a judge to release him on bail, filing in support of their request a dozen letters from lawyers, professors, pastors and other public figures who vouched for his character and promised he posed no threat to the public.

In response, prosecutors published transcripts from what they said was a wiretap on a contraband cellphone that Martinez used in a Northern California prison to direct criminal activity in Orange County. According to the transcripts, Martinez threatened to blow off a man’s head, bragged of killing four people and swore to leave his mother’s deathbed if one of his “brothers” in the Mexican Mafia required it.

Federal prosecutors say Gabriel Zendejas Chavez, a criminal defense attorney who once taught English, connected the Mexican Mafia’s bases of power in prisons, jails and the streets of Southern California.

Martinez insisted he was misquoted in the transcripts. The claim that he would abandon his mother, an oversight commissioner for the Los Angeles County Probation Department, was “straight B.S.,” he said.

Martinez said he never threatened to shoot anyone in the head or boasted of killing people, although he acknowledged saying “some not nice things” to Michael “Shaggy” Cooper, a co-defendant whom Martinez is accused of twice trying to have murdered.

Martinez, who denies hurting Cooper, said people who haven’t been to prison wouldn’t understand the way inmates talk to one another.

“I can’t address somebody like that the way I would talk to you or my mother or my brother,” he said. “It’s a different environment in here. It really is survival of the fittest.”

The syndicate once relied on associates on the streets, but court data showed that smuggled phones have given imprisoned leaders greater control over drug deals.

Prosecutors say it is not mere talk. Martinez is charged with two murders, the first occurring the night of Jan. 19, 2017, when three armed men tried to rob a small-time drug dealer named Robert Rios outside his uncle’s house in Placentia. The uncle testified his nephew’s last words before being gunned down were, “Don’t kill my family!”

According to testimony at a preliminary hearing in 2020, the slaying was orchestrated by Martinez’s alleged right-hand man, Gregory “Snoopy” Munoz, who was then serving a 12-year sentence for robbery at Calipatria State Prison. Using a contraband cellphone, Munoz arranged for a crew to obtain a car, guns, zip ties, masks and gloves before directing them to Rios’ home, a detective testified.

But the planned robbery went awry when Rios fought back. When one of the assailants fired a burst from a MAC-10 assault pistol that killed Rios, he also shot an accomplice in the leg.

The getaway driver, in his confession to police, described a scene out of a Quentin Tarantino movie: The wounded man spurting blood across the rear seats, shouting, “The homie shot me!” Munoz on speakerphone from his prison cell 200 miles away, screaming: “You guys are f— idiots!”

Eduardo Escobedo, a convicted drug trafficker who worked directly for the son of Joaquin ‘El Chapo’ Guzman, was gunned down Thursday morning in an industrial stretch of Willowbrook.

Orange County prosecutors alleged Munoz could not have ordered the move against Rios without Martinez’s knowledge and approval. But after a months-long preliminary hearing, Superior Court Judge Patrick Donahue dismissed the case in 2021, ruling that prosecutors had not even met the low threshold of showing probable cause that Martinez had participated in the crime.

That has not stopped federal prosecutors from charging Martinez with Rios’ killing — this time as a murder in aid of racketeering. Martinez, who denies involvement in Rios’ death, said that at this point he is being prosecuted out of spite.

“I embarrassed them,” Martinez said. “They held a big ol’ press conference in 2018 talking about how they were going to convict me. And I made them put their foot in their mouth when the judge said there was no probable cause. Zero. So then they take the same case, the same evidence, the same people, and they slap a RICO on it.”

The federal indictment under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, however, is more sweeping than the case in Superior Court was. It charges Martinez with drug trafficking, attempted assault, murder and attempted murder that were not alleged by county prosecutors.

Martinez claims authorities are not just targeting him in the courtroom. He alleged that Orange County sheriff’s deputies put his life in danger by falsely labeling him a snitch in a document that then turned up in the county jail and state prisons.

Carrie Braun, a spokeswoman for the Sheriff’s Department, confirmed that someone mailed to the jail a “fictitious memo” that identified Martinez as an informant, but she said the person arrested for doing so was not a sheriff’s employee. Braun declined to name the suspect, saying authorities were still investigating the person.

According to Orange County prosecutors, Munoz fell out with Martinez not long after Rios’ slaying and was stabbed on two occasions at Calipatria.

Paroled in July 2017, Munoz sent a stream of text messages to Martinez, thanking the man who allegedly ordered the attempts on his life for “forcing me out” of gang life. “That’s what made me realize, homie, that this isn’t the way,” he wrote.

Until his murder in prison two weeks ago, Michael Torres ran one of the most intricate and lucrative black market businesses in L.A. County: the jails.

According to messages filed in court, Munoz asked Martinez to protect him, claiming he’d changed his ways and now led a law-abiding life.

“If what you’re telling me is true,” Martinez replied, according to court records, “I’ll put word out there then. I just don’t want u involved in trying to run s— and disrespecting [things].”

The night of Aug. 5, 2017, a worried Munoz told Martinez that a man was circling the block where his girlfriend’s mother lived in Placentia. “I do have a weapon and I’ll use it,” he wrote in a text.

Martinez said he would “send word for them to respect the mom’s house.”

“No one will mess with you,” he told Munoz, “but you need to respect things and not start problems because then my hands are tied.”

Michael Torres, a Mexican Mafia member who oversaw gangs in the San Fernando Valley and controlled drug and extortion rackets in the Los Angeles County jail system, was stabbed to death in prison.

Three hours later, prosecutors wrote in court papers, a man wearing dark clothing walked up to Munoz and, without saying a word, fired seven shots into his back and legs as he tried to crawl away. Munoz survived his injuries.

Mejia testified he dispatched the shooter after Martinez told him Munoz’s whereabouts and said, “He needs to go.”

Mejia, who shared a cell with Munoz at Calipatria, testified he became Martinez’s new right-hand man. Mejia said his boss ordered the murders of two others: Richard Villeda, an underling accused of stealing money in a drug deal, and Cooper, who, according to Mejia, had accumulated drug debts, lied to Martinez and plotted to usurp him.

Villeda was gunned down in Orange by three men who were convicted last year of murder in aid of racketeering. Cooper was stabbed at Calipatria and attacked in a county jail by inmates who slit his throat with a razor blade in 2019.

About two-thirds of the Mexican Mafia’s 140 members are held in California prisons, which are inundated with illegal cellphones. They use the phones to traffic in drugs, collect money and order murders.

In the interview with The Times, Martinez denied directing Villeda’s murder and the attempts on Cooper’s life. He alleged that Mejia told prosecutors what they wanted to hear — that Martinez was behind every act of violence that a “rogue” Mejia ordered on his own — in hopes of getting a better deal.

Martinez claimed to The Times that the FBI’s Orange County Violent Gang Task Force has allowed Mejia to read transcripts of other witnesses’ testimony so he could tailor his own to fit the facts. The task force has even fed Mejia fast food during the coaching sessions, he added.

Martinez could barely hide his contempt for Mejia, with whom he shared a jail cell for three years. Judas Iscariot betrayed Jesus for 30 pieces of silver, he said; Mejia did it for a few burgers from Carl’s Jr.

Contacted for comment, Mejia’s attorney, Shaun Khojayan, said: “Any attempt to sway potential jurors before trial is improper. We look forward to an impartial jury rendering its verdict in this case.”

She admitted falling for a man whose embrace she had never known, who lived his days in what he called ‘paseo de la muerte.’ Death row.

Mejia, 36, has pleaded guilty to racketeering. Testifying this year at the trial of a co-defendant, he said he hopes prosecutors will seek a reduced sentence for his federal conviction and speak on his behalf to the state parole board. He has been imprisoned since he was 16 for conspiring to commit murder, attempted manslaughter and assault.

Asked by a defense attorney how many murders he took part in, Mejia said: “Actually murdering somebody, probably one — probably like one or two.” He testified he also participated in three or four attempted murders.

“Even now, really,” the lawyer asked, “you don’t care if you hurt people?”

“Of course I do,” Mejia said.

“Do you care that you’re hurting Johnny Martinez?”

“I don’t feel good about it.”

“But you do it anyway?”

“Yeah,” Mejia said.

For Martinez, the stakes could not be any higher.

Last year, a judge reduced his 1995 conviction to a misdemeanor assault, ruling that Martinez would not have been convicted of murder under the law as it is written today. The only thing keeping him behind bars is the federal case, which is scheduled for trial in 2025.

When Ezequiel Romo came home to Panorama City after 18 years in prison, he didn’t like what he saw. He told another veteran of his gang, Blythe Street, he was going to “clean out house.”

If Martinez is convicted, he will spend the rest of his life in prison with no chance of parole. Yet he remains confident that once a jury hears his story, he will walk free.

“This is the final round,” he said. “When I beat this, that’s what I’m going to call this: the final round.”

More to Read

Subscriber Exclusive Alert

If you're an L.A. Times subscriber, you can sign up to get alerts about early or entirely exclusive content.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.