Code words, smuggled phones, $50 tips: Mexican Mafia micromanages drug deals from prison

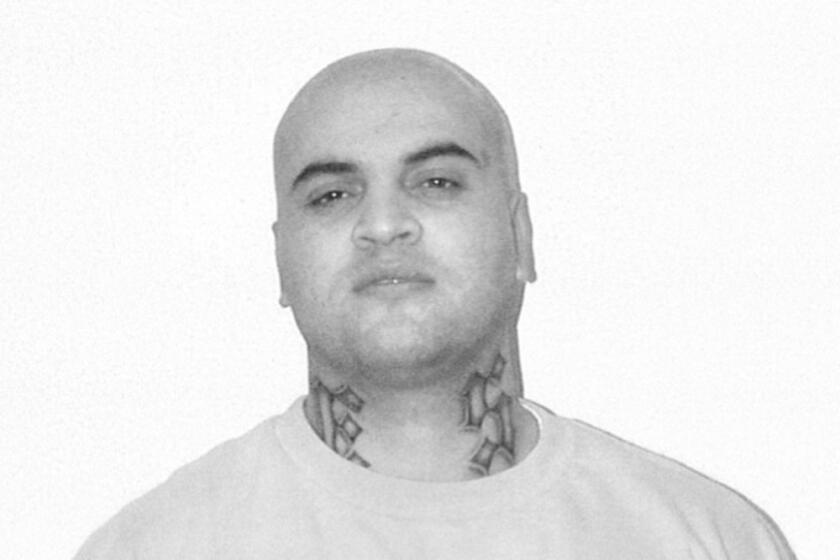

When an imprisoned gang member used a contraband cellphone to ask Miguel Maciel Jr. if he wanted to make some money, the 18-year-old jumped at the offer.

“Of course,” Maciel told the prisoner, Carlos Guadalupe Reyes, according to WhatsApp messages shown in court. “I’m always interested in money.”

The messages made clear, according to prosecutors, that Maciel was signing up for an entry-level position that offered a lot of work for little pay. In one example, his cut for delivering $900 worth of drugs and picking up the payment for his boss was $50.

“This is just the beginning homie,” Reyes wrote to him afterward. “Don’t trip you gonna make way more just be patient.”

The messages — hundreds of which were displayed in court at a recent preliminary hearing — demonstrate how the proliferation of contraband cellphones in the California prison system has changed the dynamics of drug dealing on the street, allowing incarcerated leaders to supervise young recruits from hundreds of miles away.

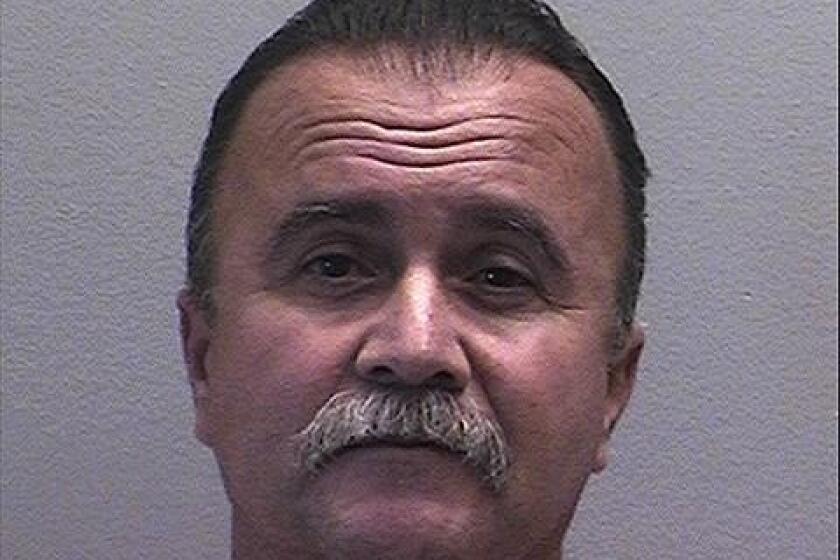

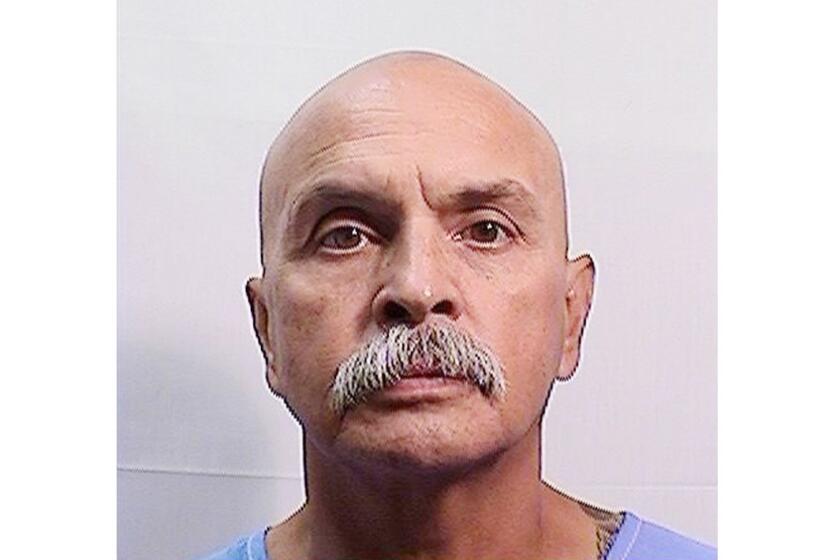

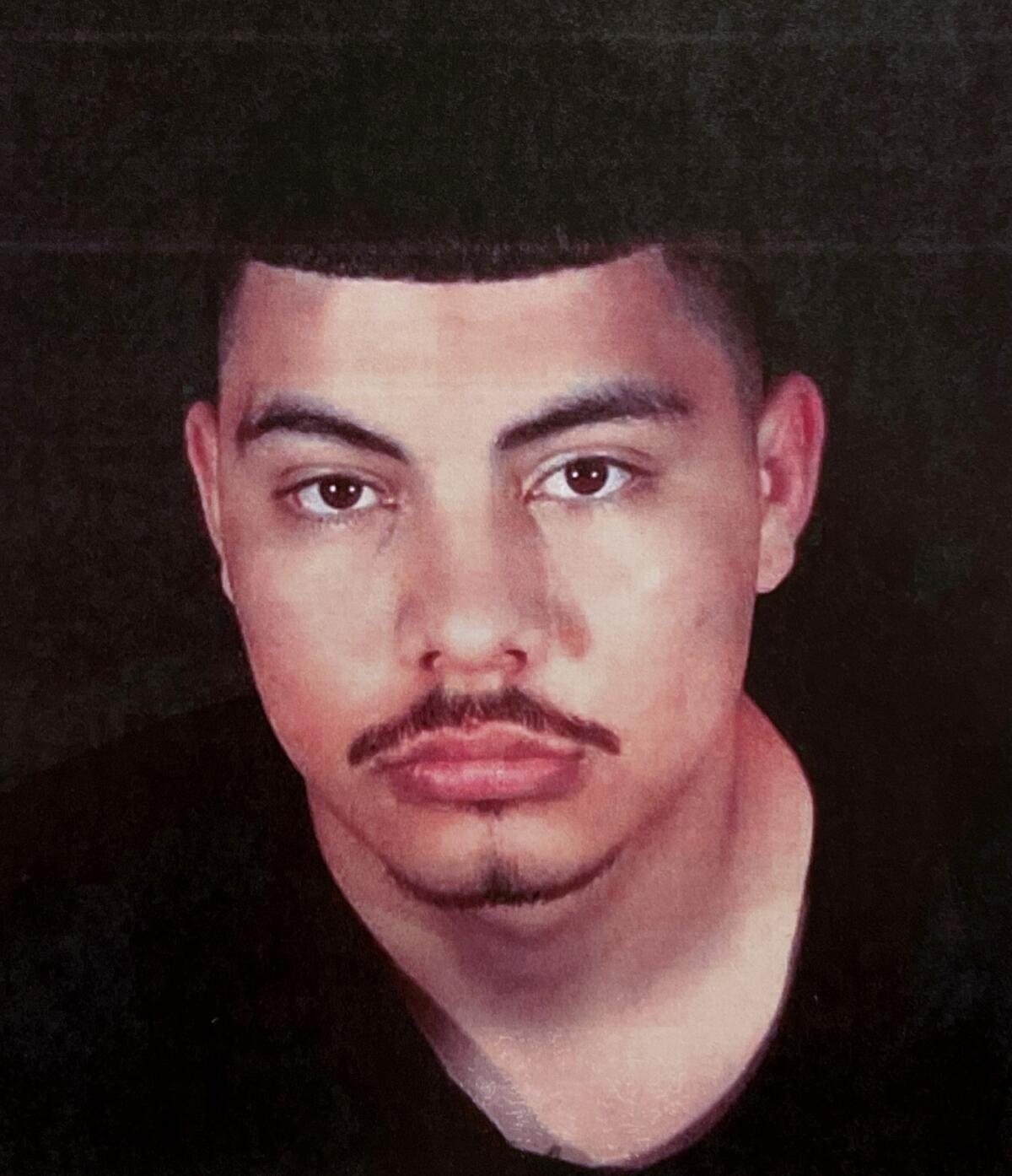

An FBI agent wrote in an affidavit that Reyes, who is serving 54 years to life in prison for murdering his estranged wife in 2008, worked under Gabriel “Sleepy” Huerta, a reputed member of the Mexican Mafia. The organization consists of about 140 men who control Latino gang members on the streets, in county jails and in state and federal prisons.

Members of the prison-based syndicate once relied on associates on the streets to collect and secure their money, which came from selling drugs and “taxing” gangs. Few had a clear idea of how much cash was being generated, Ramon “Mundo” Mendoza, a former Mexican Mafia member, told The Times.

“It totally was a matter of trust,” Mendoza said. “It’s like people who cheat on their taxes. As long as you’re not flagrantly ripping them off, you can skim.”

But cellphones allow prisoners to micromanage their drug deals. Phones are illegal for inmates to possess but are often smuggled in by corrupt staff and, in some cases, dropped inside prison walls using drones, according to testimony in a series of recent prosecutions. In requesting a budget increase of $1.8 million in 2020 to crack down on contraband phones, the state corrections department reported seizing 13,450 of them in 2019 compared with 2,811 in 2008.

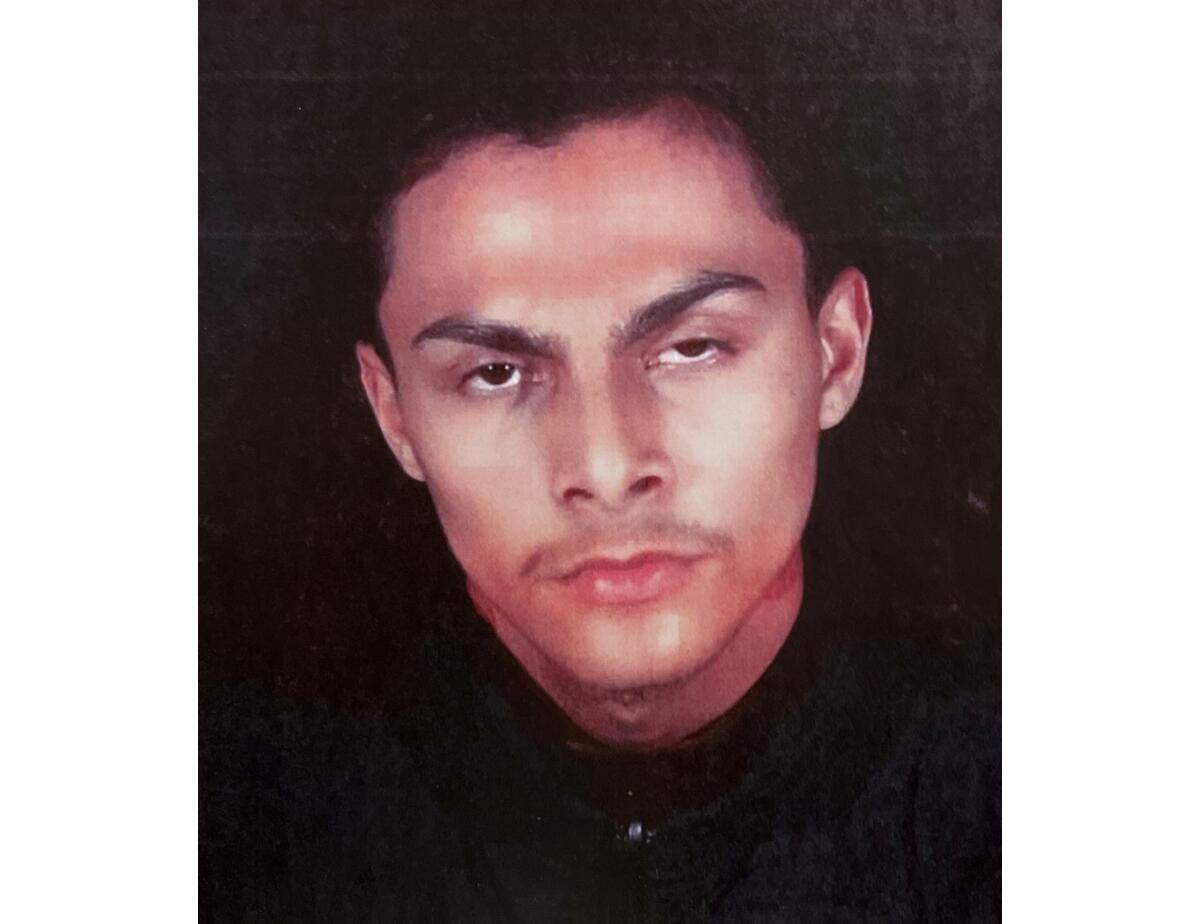

Gabriel ‘Sleepy’ Huerta is an alleged member of the Mexican Mafia’s three-man ‘commission.’ He’s been charged in a more mundane matter: the beating of a Wilmington gang member who lost a gun.

Reyes seemed to have no problem obtaining phones. He sent Maciel a photograph of four, writing, “Just because I’m in prison don’t mean that we can’t have it good.”

Prosecutors charge that Reyes, 44, arranged for methamphetamine, cocaine and heroin to be delivered to employees such as Maciel, who then distributed the drugs in smaller quantities to lower-level dealers. The WhatsApp messages, law enforcement officials say, show that Reyes acted as an intermediary with customers and suppliers, keeping his workers updated on arrival times, meeting places and code words to be exchanged.

Maciel and Reyes, both alleged members of Wilmington’s Eastside Wilmas gang, have pleaded not guilty to charges of gang participation, conspiracy and drug trafficking. At Reyes’ preliminary hearing, his attorney, Andrew Stein, argued that prosecutors failed to prove his client was the person sending the WhatsApp messages. Investigators testified they did not obtain location data confirming the phone was at Centinela State Prison in Imperial County, where Reyes was at the time.

But after reviewing the messages, listening to wiretapped calls and hearing testimony from witnesses, Los Angeles County Superior Court Judge Judith Meyer ruled she’d seen enough evidence to send the case to trial, noting there was circumstantial evidence that Reyes, whose nickname is “Wino,” wrote the messages sent under the username “Grape.”

Reyes was a hands-on supervisor, requesting updates on deliveries and regular counts of his cash, the messages show. Once, when the total was $663 less than his own estimation, he told a worker: “Let’s do the math again.” His employees expressed gratitude for their cut, small as it was. Told he had $10,000 in cash on hand, Reyes instructed Maciel to keep $100 for himself.

“Fasho goodlookin,” Maciel said. “I appreciate it.”

In one message shown in court, Reyes chided another worker for drawing unnecessary attention from the police. “I take care of my people,” Reyes wrote. “Don’t want them in here with me.”

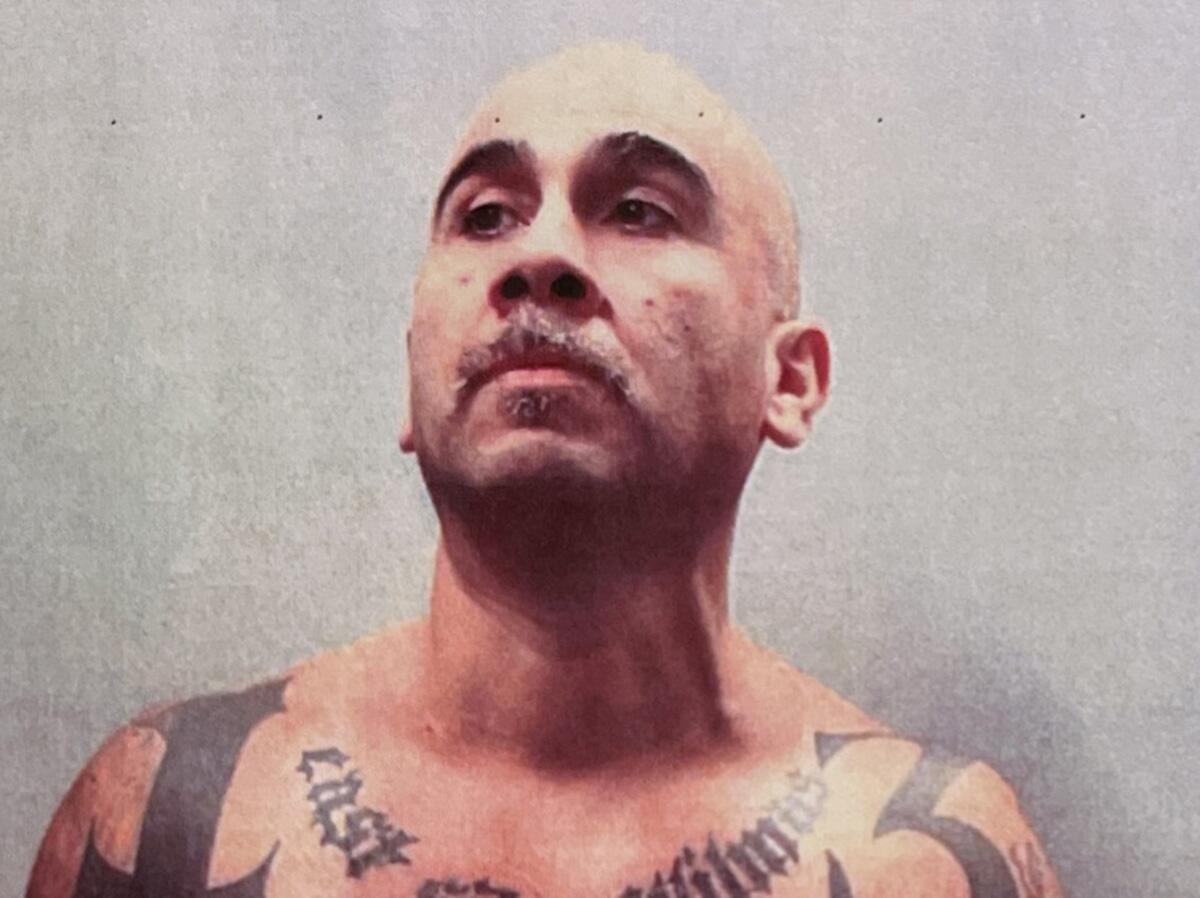

Reyes’ first runner, prosecutors allege, was Gregorio Lopez Amaya, then a 20-year-old Eastside Wilmas member nicknamed “Money.” Reyes told Lopez Amaya in January 2020 that a customer was driving to Wilmington from Moreno Valley to buy a quarter-pound of methamphetamine for $350, according to the messages.

Lopez Amaya worried about a helicopter hovering overhead, but Reyes — apparently monitoring police radio traffic with his cellphone — told him it was headed elsewhere. “The scanner said 3 suspects one has a gun,” he wrote.

After Lopez Amaya wrote “touchdown” to confirm the deal went through, Reyes told him a woman driving a Nissan Sentra would deliver $1,600.

“I’ll count it in my pad then put it away and add it to everything else and I’ll give you a total amount before I go to sleep,” Lopez Amaya wrote back.

Eduardo Escobedo, a convicted drug trafficker who worked directly for the son of Joaquin ‘El Chapo’ Guzman, was gunned down Thursday morning in an industrial stretch of Willowbrook.

At 1 a.m., Reyes wished Lopez Amaya a good night. “Gotta get up early,” the prisoner wrote. “I’m only getting a few hours sleep... Secure everything. Don’t bring no attention to yourself.”

“Got you,” Lopez Amaya said. “Clocking out.”

At times, the messages show, Reyes grew frustrated with Lopez Amaya, telling the younger gang member he was trying to keep him out of prison. “Look,” he wrote, “if I was someone else I wouldn’t give a f— about anyone or anything I’m a lifer.”

There was the time Reyes asked whether Lopez Amaya had posted photographs of heroin on social media. “This is real what we do,” he said. “Indictments come behind this it changes people’s lifes. Food for thought. This is real time what we do. It don’t carry no 18 months more like 18 years.”

“You right the last thing I want is getting myself in a indictment and bringing the team down,” Lopez Amaya said, telling Reyes he had already deleted his Instagram and Snapchat accounts.

Martin Madrigal Cazares, who reputedly controlled gangs in Ventura County from Mexico, was gunned down this month in Baja California, authorities say.

“We don’t need you in here we need you out there my boy,” Reyes wrote. “Don’t get yourself caught up just for 5 minutes of fame. Do it low key and the game will last for much longer than that.”

Reyes and Lopez Amaya mostly talked about selling drugs, according to prosecutors, but two messages appeared more sinister. Complaining of feeling “like a sitting duck,” Lopez Amaya said he was “gonna need a silencer.”

“I been wanting to go knock on the door like a high school student trying to sell a newspapers for my university and if I got the chance just boom bam done,” Lopez Amaya wrote. “But you know I got to run everything by you first.”

Reyes didn’t respond.

An attorney for Lopez Amaya, who was charged with gang participation and drug trafficking but deported before entering a plea, didn’t return a request for comment.

Despite his work for Reyes, prosecutors said, Lopez Amaya was beaten by his fellow gang members, who blamed him for losing an assault rifle during a run-in with police. In a wiretapped call after the incident, Ulices “Little Poste” Gutierrez warned Lopez Amaya’s friend to not go against “the big homies” in prison.

“You can’t say no to them ... fool. You know what I’m saying? Cause they’re the ones that control the whole hood,” said Gutierrez, who is now serving four years in state prison after pleading guilty to gang participation.

Prosecutors charge that Maciel, nicknamed “Little Chivo,” took Lopez Amaya’s place in the drug business after he was arrested on firearms charges. Maciel’s attorney didn’t return a request for comment.

“Anything you need I got you,” Maciel wrote to Reyes. “Let me know I’m trying to make money.”

Until his murder in prison two weeks ago, Michael Torres ran one of the most intricate and lucrative black market businesses in L.A. County: the jails.

Prosecutors charged that Reyes asked Maciel to deliver half a pound of methamphetamine to a woman in a fourth-floor room at the Crystal Casino in Compton.

“TD,” Maciel wrote, apparently confirming the $900 deal had gone through.

Then Reyes told Maciel to head to Plaza Mexico in Lynwood, where a man driving a red sports car would hand him a sample of black tar heroin.

“Code is peluquero,” Reyes said, Spanish for hairdresser. “Just when you see him say peluquero? He gonna know sup.”

“TD,” Maciel wrote 20 minutes later.

Reyes told Maciel to bring the heroin back to the woman at the casino, who would test the quality, then await delivery of more. “Count out 7 gs homeboy,” Reyes wrote. “They gonna go drop you off half a key which is 500 grams.”

Reyes asked for a count of the day’s earnings. “I should have 1600$ cash with you correct?” Maciel said it came to $1,580 and sent Reyes a photograph of the cash. “I’m a recount it again right now,” he said.

“It’s all good I ain’t tripping on 20$ homie,” Reyes wrote.

Reyes kept some of his money in his safe at an associate’s home, but he said he also used CashApp and Green Dot. “I do a lot of buissnes through there,” he said of Green Dot, a prepaid debit system. “I mean racks.”

The next day, after driving 30 minutes to deliver a quarter-pound of methamphetamine to a customer in Redondo Beach, Maciel was told to keep $25 from the $300 deal.

A terminally ill Mexican Mafia member expounded on the current state of the gang from his prison cell before he was released to die at home.

Reyes told Maciel, who drove a silver 2003 Honda Accord, that he’d get him a car to drive while making deliveries. He sent a photograph of a BMW to Maciel, who said it looked “f— nice.”

“What year is it?” Maciel asked.

“It’s a 2005 but it’s still a Koo as little SUV,” Reyes wrote.

That night, Maciel asked: “So what you want me to do to start making some more cheddar.”

Reyes didn’t respond. The next day, Los Angeles police pulled over Maciel in his Honda, according to a police report. He was carrying a phone that contained the messages with Reyes.

More to Read

Subscriber Exclusive Alert

If you're an L.A. Times subscriber, you can sign up to get alerts about early or entirely exclusive content.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.