‘Like the Godfather’: Mafia informant’s brother killed years after dramatic testimony, arrest made

The pickup truck circled the block in Boyle Heights, as if searching for someone, when it stopped next to a man riding a bicycle.

A gunman stuck a .45-caliber handgun out the passenger-side window and shot Eduardo “Eddie Boy” Castro six times.

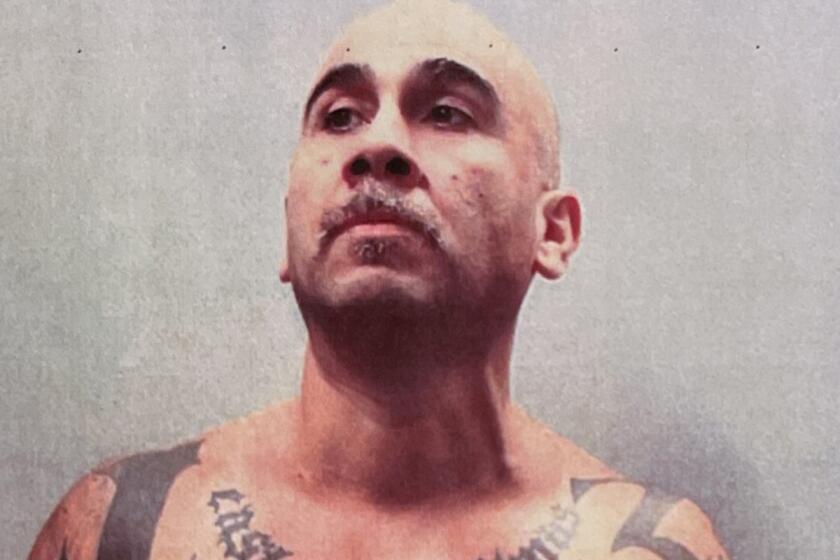

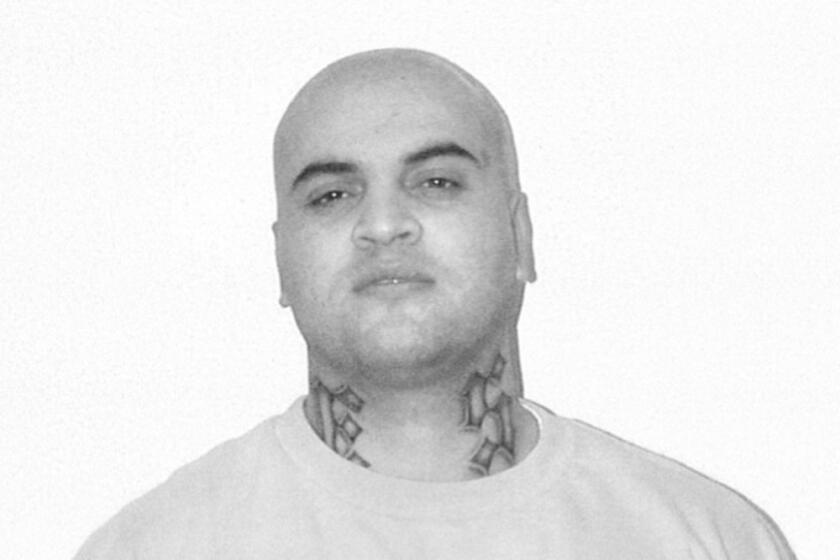

Castro, 59, had been a member of the Mexican Mafia since the early 1990s, and law enforcement officials and underworld sources said there were plenty of possible motives for his murder. He had refused to take sides in the prison-based syndicate’s perpetual wars, and incurred resentment from imprisoned members of the organization who noted he was rarely locked up himself.

But there was also his brother Ernesto — perhaps the most damaging witness in the history of the Mexican Mafia, responsible for helping prosecutors convict a dozen of his fellow members in the first racketeering case brought against the organization.

Last week, five years after Eduardo Castro was shot, detectives arrested his alleged killer.

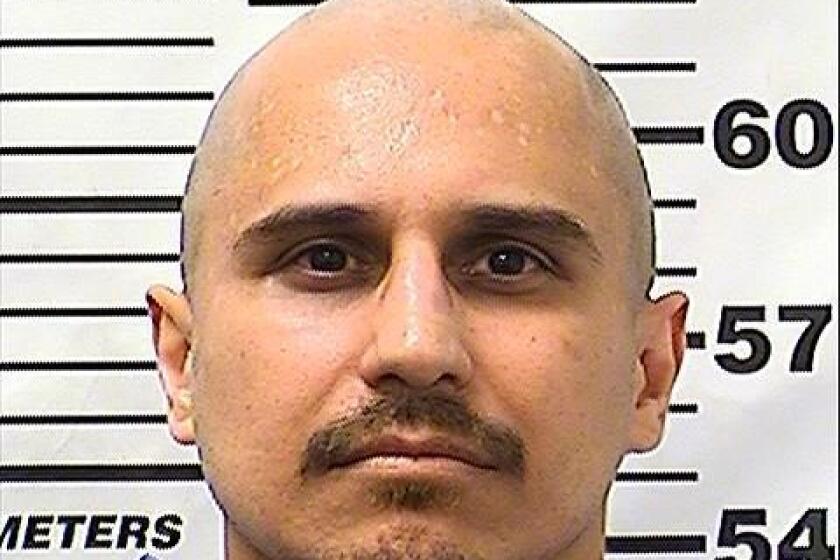

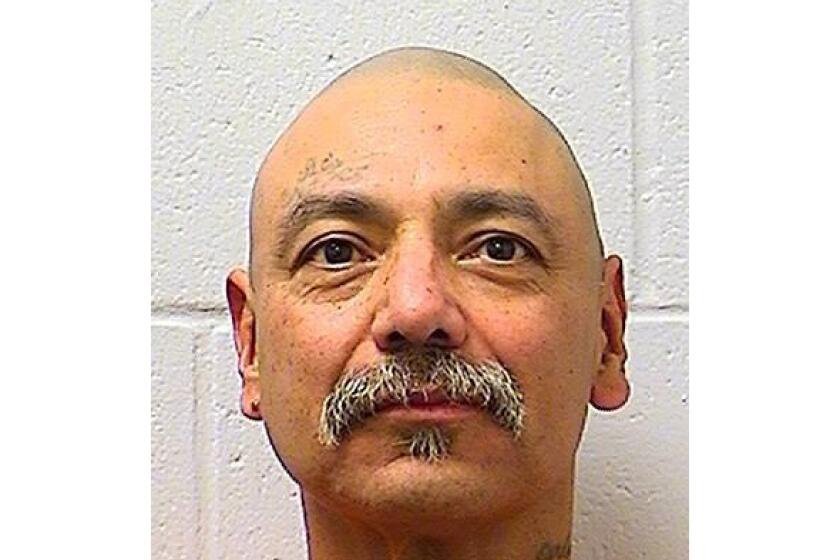

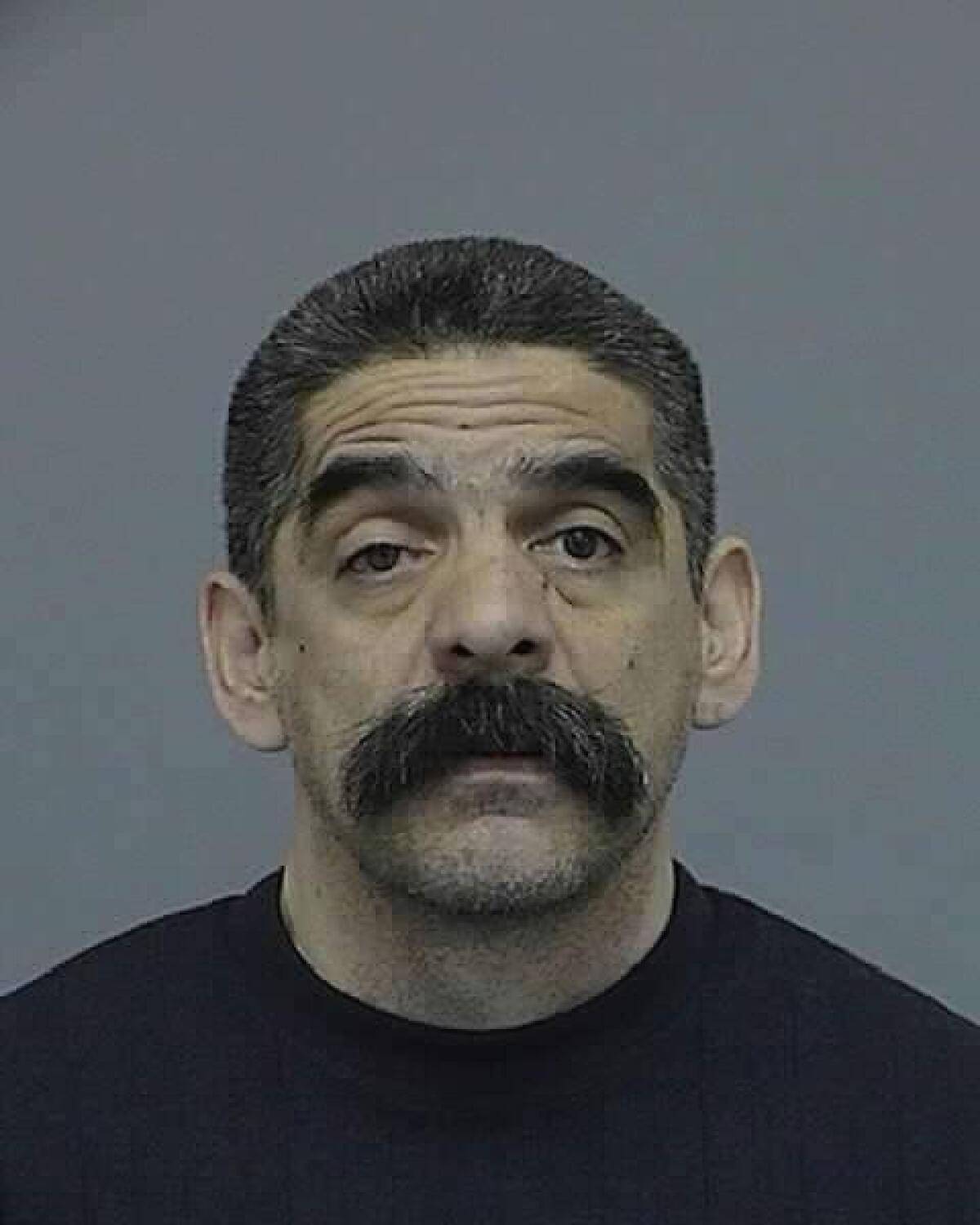

Vincent “Spanky” Armendariz, 60, was charged Monday with murdering Castro. A reputed member of a small East Los Angeles gang called Winter Gardens, Armendariz didn’t enter a plea at a court appearance Monday. His lawyer referred questions to the Los Angeles County Public Defender’s media office, which didn’t respond to a request for comment.

As a teenager, Eduardo Castro followed his older brother Ernesto into Varrio Nuevo Estrada, a gang based in the Estrada Courts housing project in Boyle Heights. Built in 1942, the project’s two-story buildings are painted with scenes from Mexican and Chicano history. One mural shows two hands holding up the letters “VNE,” an eagle alighting atop them with a banner in its beak that reads, “In memory of a homeboy.”

Ernesto, whose nickname was Chuco, was a different man than his brother, said Richard Valdemar, a retired Los Angeles County sheriff’s sergeant who ultimately convinced him to defect.

Prosecutors say Johnny Martinez was caught on a wiretap boasting of several murders, but he still has prominent voices calling for his release, including two L.A. County probation officials.

“I would say Chuco was more, well, intellectual. More about the ideas of the Mexican Mafia. Chuco was about making money, doing business. Eddie was more the gangster, the enforcer.”

In 1993, Ernesto Castro was arrested after police found a cache of guns hidden beneath his Alhambra home. Tired of the Mexican Mafia’s infighting and unwilling to return to prison, he spent the next two years wearing a wire.

The resulting case went to trial in 1997. In a scene that mirrored the attempt to silence mob turncoat Frank Pentangeli in The Godfather Part II, Eduardo glowered from the front row of the courtroom benches when his brother took the witness stand.

Ernesto was unnerved, Valdemar recalled. “You’ve got your brother staring at you, knowing he’s a member of the very organization you’re betraying. It’s very much like the Godfather.”

Unlike the fictional Pentangeli, Ernesto had no change of heart. He endured six weeks of cross-examination by lawyers for the defendants, all but one of whom were convicted.

The syndicate once relied on associates on the streets, but court data showed that smuggled phones have given imprisoned leaders greater control over drug deals.

Ernesto was racked with guilt over the position in which he’d left his relatives — some of whom renounced him and refused to follow into witness protection, Valdemar said. “He was ripping himself from half of his family. He had basically become what his gang would call a coward and a snitch. It ripped him apart.”

Valdemar said under the Mexican Mafia’s code, Eduardo would have been obligated to kill his brother if he ever saw him again or learned of his whereabouts.

“They call it cleaning up your own [mess],” Valdemar said.

Eduardo would always carry the shame of his brother’s betrayal, Max Torvisco, a fellow member of Varrio Nuevo Estrada, testified years later. Although Eduardo never cooperated with the government, “people stayed away from him,” Torvisco said.

In 1998, a year after his brother’s testimony, Eduardo found himself in the middle of a war. The Mexican Mafia was divided into two factions: a group loyal to Benjamin “Topo” Peters, one of the defendants Ernesto helped convict, and an upstart group that called itself “the majority.”

A member of “the majority,” John “Stranger” Turscak, asked Eduardo in 1998 to help set up the murder of a Peters loyalist, Mariano “Chuy” Martinez. Eduardo agreed to lure Martinez, a fellow member of Varrio Nuevo Estrada, into a meeting — only to double-cross Turscak and tell Martinez of the plot, according to an FBI report reviewed by The Times.

Martinez sought his revenge on Easter Sunday. He gathered a crew of seven men at Estrada Courts, where he passed out guns and walkie-talkies before riding in a three-car caravan to the Atwater Village home of Turscak’s mother, a witness testified.

Until his murder in prison two weeks ago, Michael Torres ran one of the most intricate and lucrative black market businesses in L.A. County: the jails.

When Turscak walked out the front door, followed by his wife and their 2-month-old baby in her arms, Martinez gave the order via walkie-talkie to kill him, according to the testimony of Torvisco, Martinez’s right-hand man.

One shooter’s gun jammed. The other fired wildly at Turscak, who ran back inside the house, Torvisco said. No one was hit. A year later, Turscak, Martinez and dozens more from both sides of the war were behind bars for parole violations and on racketeering charges — but not Eduardo.

Underworld figures who knew the younger Castro described him as a middle-of-the-road presence who never seemed to make trouble. According to an associate who requested anonymity for fear of retaliation, Castro ate breakfast every morning at Dino’s, a hamburger stand on Main Street in Lincoln Heights, whiling away the hours with a cup of coffee and puzzles from the newspaper.

By 2009, Eduardo had fallen on hard times. Ralph Rocha, a Mexican Mafia member turned informant, told the authorities he’d heard Castro was living out of a car.

According to Rocha’s statement to authorities, two brothers from the Evergreen gang were shaking down nightclub owners, claiming Eduardo had inducted them into the Mexican Mafia.

Michael Torres, a Mexican Mafia member who oversaw gangs in the San Fernando Valley and controlled drug and extortion rackets in the Los Angeles County jail system, was stabbed to death in prison.

Rocha said he asked Eduardo how he was broke while the brothers had amassed a boat, a mansion in San Diego and a racehorse called the Down Low. Rocha said Castro brushed off his concerns and refused to help track down the brothers.

Rocha told authorities that when he heard a rumor that Ernesto had been spotted in Estrada Courts, he sent an underling to request a meeting with Eduardo. The emissary was gunned down in his car.

“We just took that as him saying, ‘F— you. Come and get me,’” Rocha said, according to a recording reviewed by The Times.

Rocha put a “green light” on Varrio Nuevo Estrada — a standing order to attack its members on the street and in jail — until Eduardo agreed to meet. An informant who witnessed Rocha give the order told the FBI he had encouraged a crowd of gang members to “take target practice” on Castro’s old crew.

The conflict faded when Rocha was arrested for extortion. By 2015, however, Eduardo’s standing within his organization remained precarious.

Some 200 miles from Los Angeles at Centinela State Prison in the Imperial County desert, an inmate named Sergio Sanchez had been selling drugs without paying the customary one-third “tax” to the Mexican Mafia.

Martin Madrigal Cazares, who reputedly controlled gangs in Ventura County from Mexico, was gunned down this month in Baja California, authorities say.

According to testimony before a Los Angeles County grand jury, Sanchez argued he shouldn’t have to pay the tax because he worked for “Eddie Boy.” This set off a flurry of calls between inmates using contraband cellphones and associates outside of prison, all of whom were trying to determine Castro’s standing.

In a five-person conference call that authorities intercepted on a wiretap, a man loyal to Eduardo said angrily, “Somebody was spreading the rumor that they plucked the homie E’s wings” — that Castro was no longer recognized as a Mexican Mafia member.

“Eddie Boy,” he said, was “fed up with all of this.”

“He reached out to the Bay” — a reference to the maximum security prison at Pelican Bay — “and to everywhere he could. And he wants to know who is the one saying that.”

Many conference calls later, Castro’s status was confirmed: “EB is not good,” a man on the streets of Wilmington told a prisoner at Centinela.

Two days later, Sanchez — the inmate who had invoked Eduardo’s name for protection — was stabbed 16 times by two prisoners, according to testimony. He survived only after being airlifted to a hospital.

A defense attorney was charged in a federal indictment with conspiring to murder a Mexican Mafia member who had fallen out of favor with the prison-based syndicate.

In 2016, the younger Castro refused to participate in the assassination of Dominick “Solo” Gonzales, who had angered Mexican Mafia members in the California prison system by encroaching on their collection rackets in the San Fernando Valley, according to testimony at a recent racketeering trial.

Eduardo’s issues made him an easy target for a smear campaign by rivals who wanted his territory, said Valdemar, the retired sheriff’s sergeant who turned Ernesto as a witness. “They would politic against Eddie,” Valdemar said, “and it would be very easy because he had all these strikes against him.”

Armendariz, the man accused of killing Castro, has a rap sheet dating to 1987 that includes convictions for murder, robbery, drug sales and possessing guns and ammunition as a felon, court records show.

Sheriff’s deputies suspected Armendariz was running gambling parlors called casitas on the Eastside, according to a search warrant affidavit reviewed by The Times. He was also collecting money from smoke shops that sold illegal gaming software under names like RiverSweeps, FireKirin, SkillMine and VegasX that allowed gamblers to play blackjack, poker and pai gow on their phones, a detective wrote in the affidavit.

According to the affidavit, Armendariz was kicking up money from gambling houses and smoke shops to two imprisoned Mexican Mafia members.

Casitas represent ‘more than just gambling,’ says a Los Angeles sheriff’s detective. ‘It’s extortion, it’s murder, it’s assault.’

More to Read

Subscriber Exclusive Alert

If you're an L.A. Times subscriber, you can sign up to get alerts about early or entirely exclusive content.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.