Hidden illegal casinos are booming in L.A., with organized crime reaping big profits

One thing was clear from the body lying in the Boyle Heights street: The woman was no victim of robbery.

Whoever pumped four bullets behind her left ear didn’t touch the $1,000 in her purse, the bills clutched in her left hand or the diamond ring on her right index finger.

Detectives eventually would learn the woman was part of an underground gambling circuit booming in Los Angeles. She had worked at an illegal casino known as a casita. Like modern-day speakeasies, they are hidden in homes, in warehouses, in the backrooms of smoke shops and behind storefronts that pretend to be legitimate businesses.

Offering mostly electronic forms of gambling, casitas — Spanish for “little houses” — can bring in tens of thousands of dollars a week. The ultimate beneficiaries, authorities say, are members of the Mexican Mafia, the prison-based syndicate that oversees Latino street gangs in Southern California. These men, nearly all of whom are incarcerated, collect a share of the gambling profits in exchange for allowing the casitas to operate in their territory.

“All of these places, someone in the Mexican Mafia has their hand over it,” said Richard Velasquez, a Los Angeles County sheriff’s detective who has busted scores of casitas.

With so much money at stake, Mexican Mafia members and their underlings have little tolerance for anyone who disrupts their rackets, authorities say. Those suspected of stealing from casitas have been beaten, shot, kidnapped and killed, court records show.

About two-thirds of the Mexican Mafia’s 140 members are held in California prisons, which are inundated with illegal cellphones. They use the phones to traffic in drugs, collect money and order murders.

Illegal gambling parlors have other names, including “nets” — short for internet cafes, businesses that in the early 2000s were commonly used as fronts. They are also called “tap taps” and “slap houses” for the sounds — audible from outside the parlor — of gamblers furiously working the joysticks and buttons of their most popular attraction: the fish game.

It’s played on a machine that looks like a pool table with a screen where the felt would be. Gamblers sit around the table, manipulating joysticks to harpoon digital fish flickering across the screen.

Investigators have found casitas “everywhere, to be honest with you,” Velasquez said. “It’s hidden in plain sight. You don’t know that it’s there till you know that it’s there.”

Deputies recently raided a casita in an unincorporated area of Hawthorne, inside a storefront tucked between a hair salon and a Mexican restaurant on Inglewood Avenue. Signs for “Slipt Stitch Yarn Shop” and “knitting and crochet clases” hung from its facade.

Inside was a gambling operation in plain view. Asian music wafted from speakers. The air smelled of cheap disinfectant. Walls were painted in greens, reds and pinks with images of fish, turtles, jellyfish and seaweed. Messages written on the walls put those who came in on notice:

“If you’re not playing, you’re not hanging out”

“Do not bang on machines”

“Clean up your trash! We are not your maid!”

Written on a bathroom wall was a warning: “If we find out or even suspect it you will be banned.” Velasquez guessed this referred to drug use. No narcotics, pipes or syringes were found inside the casita.

Two fish tables and a slot machine were set up against one wall. A bank of computer monitors, some logged into a gambling program called BlueStacks, lined the other.

Above a sliding partition that functioned as a cashier’s window, this information was posted: “Max payout $1,000. We take EBT min $250.” Velasquez said some casita operators will use a patron’s EBT card — state benefits intended to be used to buy food — to purchase supplies in exchange for gambling credit.

On the other side of the window was an office, outfitted with a money counter, a small Christmas tree, a mini-fridge, packs of batteries and a coffeemaker. Taped to one wall were fake $100 and $20 bills and a list of people banned from the casita: Neesia, Rich, Tatiana, G-Boy, Steve S, aka Steve-Boy, and Lissaw.

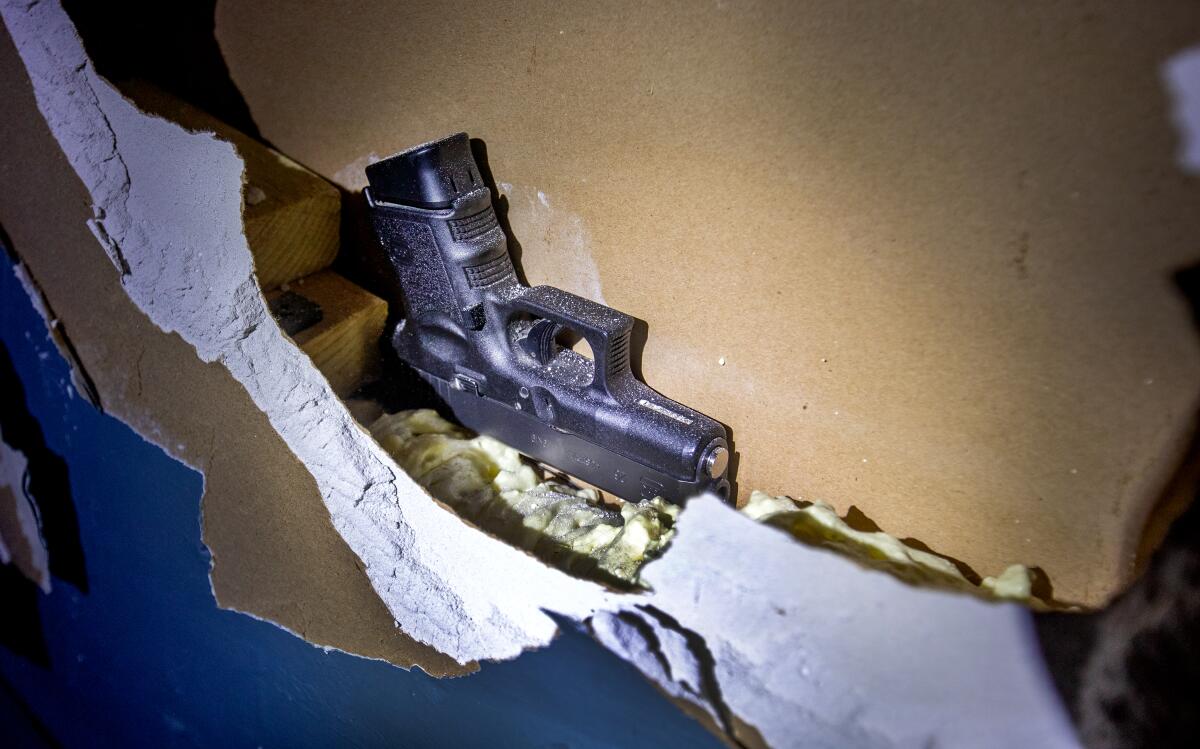

It could have been any office — save for the Glock handgun hidden behind a wall.

Detectives detained eight people inside the casita. Lined up in handcuffs in an alley behind the shop were old men, middle-aged women, a surly looking man with a face tattoo and a young blond woman wearing a white furry coat.

A neighbor, watching them being questioned by detectives, said approvingly, “Take all them fools out of here.” He said he has seen parents leave children in their cars while they gamble.

The detectives finished searching the casita, cataloged evidence and loaded the fish tables onto a flatbed. Then they let the detained patrons go. Returning to her car, one woman said she had only gone to the parlor to “check my email.” Another said she was there for the “free Wi-Fi.”

Anyone profiting from illegal gambling — whether operating a casita or running online gaming from a smoke shop — is subject to being “taxed” by the Mexican Mafia, Velasquez said.

An organization of about 140 men, the Mexican Mafia has harnessed its control over Latino street gangs in Southern California into extorting criminals who operate within those gangs’ territories: drug dealers, car thieves, credit card scammers and casita operators, among others.

Authorities also have found instances of Mexican Mafia members taxing Asians and Armenians operating gambling parlors in the San Gabriel and San Fernando valleys, according to interviews and records obtained by The Times.

“The way I see it, the Mexican Mafia is not much different than the Italian mob,” Velasquez said. “You open a smoke shop, you’re selling gaming software or you have a [gambling] machine, some Southsider” — a gang member working under the Mexican Mafia — “is going to walk in there and say, ‘Hey, you can’t do this in our area without our permission, without our protection.’ ”

Given the clientele — often gang members and drug users — casitas have been the scenes of impromptu assaults and shootings. Last March, a 29-year-old man was killed during a dispute inside one operation in Temple City.

In some cases, however, the violence is business-related.

Federal prosecutors say Gabriel Zendejas Chavez, a criminal defense attorney who once taught English, connected the Mexican Mafia’s bases of power in prisons, jails and the streets of Southern California.

One woman testified she was pistol-whipped and kidnapped after money came up missing on one of her shifts at a casita in Baldwin Park.

A member of the Eastside Bolen gang held a gun to her back as he marched her into the casita, which was inside an abandoned warehouse near the interchange of the 605 and 10 freeways. Inside, another member of the gang shot her twice in the back, she said at a preliminary hearing in 2021.

Told “that I need to pay up,” she promised the gang members that a friend staying at a motel in Monrovia had her government check and some money her grandmother left her when she died. They drove the bleeding woman to the motel, where she managed to escape in the parking lot.

Two Eastside Bolen gang members have been charged with kidnapping and attempting to murder the woman, while a third defendant faces kidnapping charges. They have all pleaded not guilty and have yet to go to trial.

Casita operators who refuse to pay the tax can expect to have their shop vandalized, their equipment stolen or their tires slashed, Velasquez said. “They’re going to create the problem that you need protection from. And then once they have you, you belong to them. They’re going to keep taking and taking.”

For tax collectors used to picking up a few hundred dollars a month from drug peddlers, the gambling profits can seem enormous.

When Michael Haynie got out of prison in 2016, a reputed Mexican Mafia member, Frank “Playboy” Fernandez, gave him “the keys to my hood” — the authority to run his gang, Stoners-13, and take money from anyone doing illicit business in their East L.A. territory, Haynie testified at a recent murder trial.

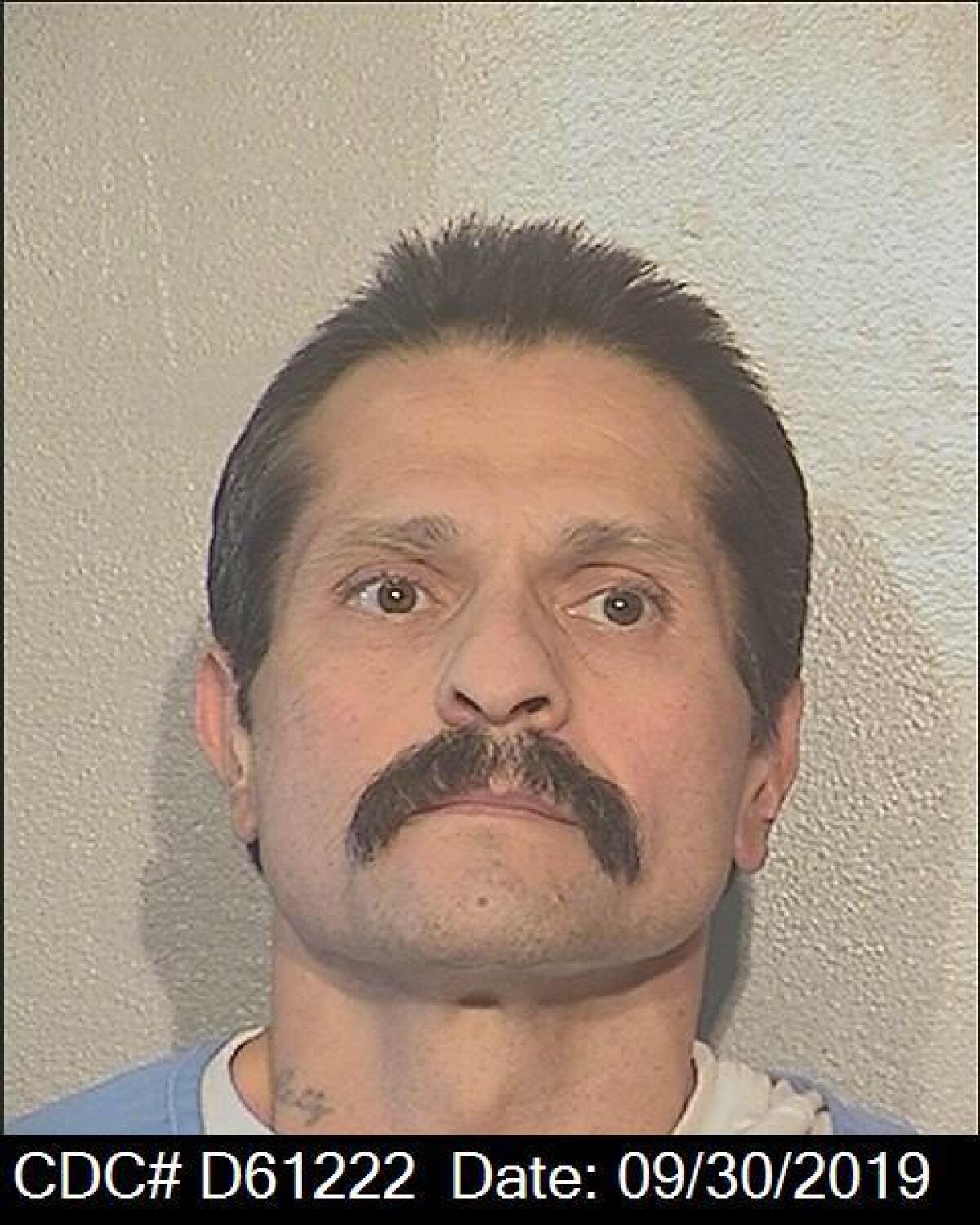

Fernandez, who denied to the parole board being affiliated with the Mexican Mafia, has been imprisoned since 1986 for kidnapping, according to records. He told the board that informants were lying when they said that “I’m making millions of dollars from my jail cell or I’m coordinating this or that.”

Haynie testified that he collected as much as $80,000 a month from two casitas in East Los Angeles, one at Whittier Boulevard and School Avenue and the other at Olympic and Goodrich boulevards.

According to Haynie, he delivered the money to people working for Fernandez’s right-hand man, Francisco “Cora” Celis, who is serving life without parole for a 1996 murder. Celis is described in an FBI report as a Mexican national with “his own drug trafficking network” from Mexico who worked with multiple Mexican Mafia members.

Stephanie Marie Rojas worked at another casita allegedly controlled by Fernandez.

Rojas had grown up in South L.A., the oldest of three children. After moving to Huntington Park, she dropped out of high school and “started hanging around the wrong kind of people,” her mother, Virginia Montalvo, said in an interview.

Rojas had her first of three children, a daughter, when she was 21. With Rojas cycling in and out of jail, Montalvo raised two of them.

In 2014, Rojas pulled a 1994 Honda Accord into the Mexican side of a border checkpoint near San Diego. Customs inspectors found four kilograms of methamphetamine hidden behind the car’s rocker panels, court records say.

Admitting she’d been promised $3,000 to smuggle the drugs, she pleaded guilty and served 30 months in federal prison. After getting out, she told her mother she’d found work at a flooring and tile business.

“She’d say the less I knew, the better it was,” Montalvo recalled.

At some point Rojas began working as a cashier at a casita with “wall-to-wall machines” on Whittier Boulevard, next door to a bakery, said Det. David Alvarez of the Los Angeles Police Department.

Subscribers get exclusive access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers special access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Explore more Subscriber Exclusive content.

Like all casitas, this one worked hand in hand with local gang members to ensure business wasn’t interrupted. “They try to keep it under control,” Alvarez said. “There’s always a gang working with the owner to keep things, whatever problems, outside of the casita.”

Around 5 a.m. on Aug. 29, 2018, Rojas walked out of the casita and onto Euclid Avenue, “lured by a text by an unknown suspect who may have been known to her,” a probation officer wrote in a report.

Neighbors told police they heard gunshots, a coroner’s report says. A few minutes later, a motorist saw a body in the street and called 911.

Rojas was wearing a burnt orange dress and white sandals. Tucked inside her bra was a bag of methamphetamine. She was clutching a phone and $58 in bills in one hand and wore a diamond ring on the index finger of the other. Police found $1,000 in the black purse beside her body.

Detectives learned why she’d been killed only after a gang member was arrested a year later in San Diego for smuggling drugs from Mexico.

Testifying at a recent hearing, Anthony Marino said he was hanging out at a smoke shop he ran on Beverly Boulevard when Armando Butron, a member of the King Kobras gang known as “Stoney,” told him he’d killed a woman at a “casino.”

“I had to take care of her,” Marino recalled Butron saying, adding that a man nicknamed “Spanky,” who has not been charged in the case, “got the word to go ahead and do it.”

A gang member was caught smuggling drugs into Los Angeles County’s main jail. He was, authorities say, just one cog in the Mexican Mafia’s lucrative operation in the county jails.

Dressed in a blue jail jumpsuit and wearing a rosary, Butron stared across the courtroom at Marino, who didn’t return his gaze as he testified: “He just said he shot her in the head.”

Prosecutors showed evidence at the hearing that Rojas and Butron were in a romantic relationship.

Arrested three years after Rojas’ death, Butron was placed in a holding cell rigged with hidden recording devices. Det. Carlos Camacho testified that Butron told his cellmate he’d been charged with murdering a woman and that “Playboy” had “made the call for her to be killed.”

Fernandez, 59, has not been charged in Rojas’ murder. Reached by a Times reporter, he wrote in a letter from Pelican Bay State Prison: “I am in the blind here and have no idea of any cases that I am involved in nor have I been summoned on.”

Held on $2.1-million bail, Butron, 25, has pleaded not guilty to charges of murder and possessing a gun as a felon.

The probation report filed in his case offers two reasons why Rojas may have been killed: She had been accused either of skimming from the casita’s profits or helping set it up to be robbed.

Montalvo saw her daughter for the last time about three months before she was killed, when she came over for breakfast with her children and brothers. Rojas never told her she was working at a casita.

“She kept it all to herself,” Montalvo said, her voice stiff with anger. “And look at where it got her.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.