Sheriff’s deputies led Luis Garcia from his cell to the visiting room at Men’s Central Jail in downtown Los Angeles. The man waiting on the other side of the glass partition introduced himself as Gabriel. “I’m here for...,” the man said, then raised his palm to the glass.

To Garcia, a gang member who has admitted to selling drugs and running extortion rackets behind bars, the gesture was unmistakable: The man had come on behalf of the Mexican Mafia, the prison-based crime syndicate whose symbol is a black hand.

But he wasn’t a gangster. He was a lawyer.

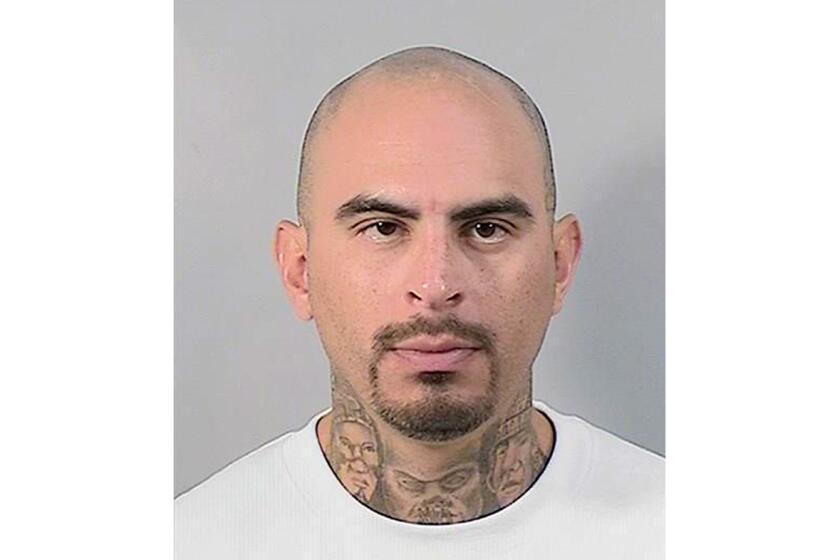

Garcia recalled the 2014 meeting while testifying in late August against Gabriel Zendejas Chavez, the man who had visited him in jail. Federal prosecutors had accused Chavez of playing a vital role in the Mexican Mafia, alleging the criminal defense attorney had connected the organization’s bases of power in prisons, jails and the streets of Southern California.

Using the protections granted to attorneys as a shield, prosecutors charged, Chavez conferred with underworld figures in the country’s highest-security lockups, relaying orders to have people beaten and killed, and exposing government informants whom he’d ferreted out through his access to case files.

To make their case, prosecutors called into court a parade of gangsters, drug dealers and shakedown artists who testified that the lawyer plotted with them to deal drugs, extort from inmates and tamper with witnesses.

A gang member was caught smuggling drugs into Los Angeles County’s main jail. He was, authorities say, just one cog in the Mexican Mafia’s lucrative operation in the county jails.

Chavez, 45, took the witness stand to claim he was a victim — both of criminals who threatened him into going along with their schemes and of authorities who resented his aggressive representation of accused gangsters.

In the end, a jury couldn’t decide what to believe. With the panel split 6 to 6 on a racketeering count and deadlocked on drug trafficking charges, the judge declared a mistrial and set a new trial date for January.

Questions of guilt and innocence aside, it was clear that Chavez, who worked as a high school teacher before going into law, had in a short amount of time become immersed in a dangerous underside of society. He acknowledged as much when he told the jury, through tears, “There’s no manual for this situation.”

Within the Mexican Mafia, two immutable truths will always be in conflict.

The organization has no formal hierarchy, no leader or board of directors. All of its 140-some members have equal say, at least in theory. Decisions that affect the group as a whole, such as inducting a new member or killing an existing one, must be reached by consensus.

This requires communication. Yet nearly all Mexican Mafia members are scattered across California and other states in jails and prisons, where their mail is read, their phone calls are recorded, their visits monitored.

It was these conditions, prosecutors argued to the jury hearing Chavez’s case, that made a little-known defense attorney invaluable to one of California’s most feared criminal organizations.

‘I had a fear that if he felt I did a poor job, there’d be retribution.’

Until 2011, Chavez had been an English teacher, working at Ganesha High School in Pomona and Chino Hills High. Taking classes at night, he earned a degree from Irvine College of Law, a for-profit school in Cerritos, then opened a law practice with a classmate in Ontario.

In 2013, Chavez said he got a letter from Robert Ruiz, a Mexican Mafia member from the Lomita Maravilla gang in East Los Angeles. Ruiz had gotten the lawyer’s name from another gang member, Chavez testified.

Known as “Peanut Butter” and “Chino,” Ruiz, then 69, had been sentenced under the state’s “three strikes” law and was serving 55 years to life for possessing heroin and a makeshift syringe in prison.

California voters had recently approved Proposition 36, which allowed some third-strike inmates to be resentenced if, like Ruiz, they were doing time for a nonviolent offense.

In a visiting room at Pelican Bay, a maximum-security prison near the Oregon border, Chavez cautioned Ruiz that he’d never handled a Proposition 36 petition. “I didn’t know anyone who had done one,” he testified. And as a new lawyer who’d never met a Mexican Mafia member, “I had a fear that if he felt I did a poor job, there’d be retribution,” Chavez said.

Chavez agreed to take the case. Ruiz, he testified, was concerned Rene “Boxer” Enriquez, a former Mexican Mafia member turned government cooperator, would testify against him in an effort to keep him in prison.

To prepare for whatever Enriquez might say, Chavez said he began traveling to prisons and jails up and down the state, meeting with dozens of Mexican Mafia members.

Garcia and Chavez remember their first meeting differently.

Garcia, who is nicknamed “Hefty,” had been a member of a small gang in Compton, Barrio-13, since he was 15. He told jurors that he cycled through jails and prisons for several decades before getting arrested in 2013 for setting fire to a Kmart, then looting the store when the alarm went off.

Chavez testified that Garcia’s sister asked him to take on her brother as a client. At the jail, Garcia “was interviewing me, basically,” asking about his fees and experience representing gang members, Chavez said.

But Garcia told jurors the meeting had been about Ruiz. He recounted how the inmate in the cell next to his, a Mexican Mafia member named Jose Landa-Rodriguez, said Ruiz was going to be released and that Garcia should pull together a few thousand dollars to help him get on his feet. Landa-Rodriguez said he should expect a visit from someone “who was helping out the carnales,” a term Mexican Mafia members use to refer to one another.

Rene Enriquez, a Mexican Mafia member who defected 18 years ago and helped law enforcement authorities incarcerate dozens of his onetime confederates, was denied parole for a fifth time.

After holding his palm up to the glass in the visiting room, Chavez said he was “there for Chino,” Garcia said.

It was the first of many meetings between Garcia and Chavez, according to visitation records shown to the jury. Sometimes they talked about Garcia’s mounting legal problems — not only was he facing arson charges, he had tried to kill an inmate with an icepick — but mostly they talked about business, Garcia testified. Extortion. Uncovering informants. Tracking down witnesses. Having people beaten and stabbed.

Asked to describe Chavez’s demeanor, Garcia told the jury: “It’s like if me and this other person were discussing this cup of water here,” motioning to a cup on the witness stand. “It’s a normal conversation.”

Chavez also met many times with Landa-Rodriguez, Garcia’s neighboring cellmate.

Prosecutors say Landa-Rodriguez, 57, controlled the drug trade and extortion rackets in the county jails that brought in tens of thousands dollars a month. He has pleaded not guilty to charges of racketeering and narcotics trafficking in a 70-defendant case that includes Chavez and Garcia.

Chavez testified he visited Landa-Rodriguez to discuss his immigration status and the possibility of representing him in a conspiracy-to-murder case.

After holding his palm up to the glass in the visiting room, Chavez said he was ‘there for Chino.’

Landa-Rodriguez came to regard Chavez — whom he called “Corbata,” Spanish for “necktie” — as a vital link to his allies in the country’s most restrictive prisons, Garcia testified. “Corbata is good gente and we need to protect him on that,” Landa-Rodriguez wrote in a note that Garcia said he passed between their cells. “No one else need to know but me and you.”

Thanks to Garcia, however, the FBI would know too. A month after meeting Chavez, the inmate told agents that an attorney named “Zendejas” was “helping out the Mexican Mafia,” testified Joseph Talamantez, an FBI agent who had been investigating drug trafficking in the jails for about two years.

Chavez’s attorney, Meghan Blanco, argued it was the FBI who first told Garcia about the lawyer, not the other way around. Garcia needed “something good” to get out from under cases that threatened to put him away for life, Blanco told the jury, and “the best thing he could provide the government with was Mr. Chavez.”

“Suddenly, overnight — literally overnight — Hefty Garcia comes forward and says, ‘He’s planning to have people murdered, he’s planning to have people “sat down,” he’s laundering money,’” she said.

The fact that Chavez was an attorney whose conversations with clients were privileged prevented the authorities from monitoring him closely, Talamantez testified. Agents were not allowed to surveil his office, obtain his cellphone records or scrutinize his finances. But they took the extraordinary step of directing Garcia to wear a wire in the attorney visiting room at Men’s Central Jail during a meeting with Chavez. The 52-minute tape was played for the jury.

Switching between English and Spanish, Garcia raised the issue of “the Motos” on the tape. He explained to the jury he had been referring to the Mongols motorcycle club, whose incarcerated members had been kept in protective custody since a Mongols member had killed a Mexican Mafia member years earlier.

Garcia testified that he and Chavez were discussing a plan to demand a $100,000 payment from the Mongols in exchange for a promise their members would be safe returning to general population yards in prisons and jails. On the recording, Garcia said, “We had asked them for” — he paused — “big ones.” During the pause, he testified, he wrote “100,000” on a piece of paper and held it to the glass for Chavez to see.

The men discussed how other Mexican Mafia members might be wary of the deal, believing the Mongols didn’t screen recruits to weed out informants and undercover agents.

‘Meeting with the enemy’: Was the leader of the Mongols motorcycle gang a double agent for the feds?

Three years after a federal jury convicted the Mongols of racketeering, a recording surfaced suggesting their leader had a secret relationship with the agent who led the investigation.

But “once they see this,” Chavez said — Garcia testified the lawyer rubbed his fingers together in a money gesture — “then you can please the others.” Garcia said he understood Chavez to mean that once they had the Mongols’ money in hand, most Mexican Mafia members would support the deal.

Chavez told Garcia that he was going to Pelican Bay in two months to talk to “the heaviest ones,” and “hopefully by that time there’ll be...” Here, Garcia said, Chavez again rubbed his fingers together.

Garcia testified that he passed Chavez a phone number for the Mongols’ president, David “Little Dave” Santillan, in hopes Chavez, Ruiz and Santillan could work out a deal.

Chavez’s attorney called Santillan as a witness. The Mongols’ onetime leader, who has been drummed out of the club after being branded an informant, denied knowing anything about a shakedown by the Mexican Mafia. “We have no agreements with that organization at all,” he testified.

Did he ever speak to anyone about such a deal? “Never,” Santillan said. “We don’t pay.”

On the recording, the conversation turned to a gang member nicknamed Lucky, who Chavez said was the government’s “No. 1 witness” in a Mexican Mafia case.

Later, Chavez said he was “95% sure” that Lucky “was a done deal.”

“Done deal. OK? And you know who told me? This guy told me.” Garcia testified that Chavez wrote down the names of two Mexican Mafia members.

The ruling comes nearly a year after the Mongols’ attorney filed a motion for a new trial, claiming the club’s president had acted as a federal informant.

It was clear, Garcia testified, that Chavez was saying Lucky would be killed. Chavez denied this. He told the jury he meant the gang member was entering protective custody.

It’s unclear what happened to Lucky.

At another point in the recording, Garcia offered Chavez money, but the lawyer refused. “Listen, save it…,” he said. “Right now we are cool.”

Garcia testified that Chavez even rebuffed reimbursement for travel expenses, saying, “I’m not doing this for the money.”

On the witness stand, Chavez acknowledged discussing “a lot of illegal things” with Garcia but insisted he had “zero intention” of doing them.

He claimed that when he refused in an unrecorded conversation to go along with the Mongols shakedown, Garcia replied that Chavez “was now a witness against him.”

“And he said, ‘You know what happens to witnesses,’” Chavez recalled.

Asked why, if he felt frightened by Garcia, he returned to jail to continue the conversation a few weeks later, Chavez burst into tears and stammered: “He threatened my daughter.”

Prosecutors immediately objected. After a heated back-and-forth, U.S. District Judge George H. Wu told the jury it could not consider Chavez’s testimony about the alleged threat.

One afternoon in 2014, Chavez told the jury, he was sitting in his Ontario office when Ruiz stopped in and mentioned he was having lunch next door at a Mexican restaurant owned by Chavez’s family. Ruiz had gotten out of prison six days earlier after Chavez won his resentencing petition.

When the lawyer saw the men at Ruiz’s table, he said he thought: “Oh, my God, they look like mafiosos.”

He testified that he spoke only briefly with some of them about their legal problems before leaving to pick up his daughter from elementary school. He was “embarrassed,” he said, that his relatives might think he associated with those people: “They look very — it’s not the typical clientele. I didn’t want them to think I was bringing in riffraff.”

‘Corbata is good gente and we need to protect him on that,’ Landa-Rodriguez wrote in a note that Garcia said he passed between their cells.

One of the men at the restaurant, Miguel “Pee Wee” Rodriguez, told the jury a much different story. Ruiz, he said, had called the meeting to discuss Arthur “Turi” Estrada, a Mexican Mafia member from Rancho Cucamonga.

From his cell at Corcoran state prison, Estrada had used a contraband cellphone to take control of the drug trade on prison yards across the state and in the streets of the Inland Empire, Rodriguez said.

“A lot of carnales were already politicking on him, saying he was greedy with his yards and wasn’t sharing the wealth,” he testified.

When Ruiz got out of prison, he sought a meeting with Estrada’s brother, George “Domingo” Estrada, to clear up the problem, Rodriguez told the jury. According to Rodriguez, George Estrada replied, “Let me see if I have time,” which Ruiz considered an insult.

Rodriguez, who had started working for Arthur Estrada in prison, went to the restaurant to represent his boss. George Estrada did not attend. “I was a little nervous that day,” Rodriguez recalled. “I was going to meet with some very powerful people. … I thought I might not come out of that alive.”

Rodriguez testified that Chavez sat at their table, “calm and relaxed,” as Ruiz blamed Arthur Estrada’s problems on his brother. Ruiz believed George Estrada was ordering stabbings and beatings of inmates under his brother’s authority but without his knowledge.

“This is not Turi’s character,” Ruiz said, according to Rodriguez.

Chavez had ties to another man at the meeting, Raphael “Ere” Lemus. Lemus’ parents and Chavez’s mother were from the same town in Michoacan, and had immigrated together to the Inland Empire city of Chino in the 1960s, Chavez testified. Growing up, he would see Lemus at weddings and quinceañeras.

Carmen Rodriguez was the victim of an assassination ordered by others in the Mexican Mafia and carried out by her husband’s underlings.

The discontent with Estrada and his brother would only deepen.

In a meeting at Chavez’s office, Rodriguez recalled Lemus saying other Mexican Mafia members “were going to take all [Estrada’s] power, all his prisons and assault anyone who was still working for him.” At this point, Chavez told them not to talk inside his office.

Outside, Lemus said Chavez was going to Pelican Bay to get approval from other Mexican Mafia members to “bench” Estrada, or strip him of power, Rodriguez testified.

Once, when Rodriguez met Lemus at a Jack in the Box to hand over the weekly money he collected on Ruiz’s behalf, Lemus said George Estrada had ordered the stabbings of two inmates at Calipatria state prison who worked for Ruiz.

“We’ve finally had enough of Turi,” he recalled Lemus saying. As for Estrada’s brother, “he told me he wanted to be the one to kill him,” Rodriguez said.

Asked why, if he felt frightened by Garcia, he returned to jail to continue the conversation a few weeks later, Chavez burst into tears and stammered: ‘He threatened my daughter.’

On Sept. 14, 2014, Estrada’s right-hand man was gunned down in Tijuana. Two months later, George Estrada was shot to death in his car in Ontario. Both homicides remain unsolved.

Indicted alongside Chavez in 2018, Lemus remains at large. Ruiz died in 2016 of natural causes in Tijuana.

The jury was shown a note seized in county jail. “As of 9/15,” it read, “all the carnales came into alliance to strip down Turi from all his yards and sillas” — Spanish for chairs, a reference to the seats Estrada’s associates held on councils of gang members that control prison yards — “as well and their just waiting on a decision from the committee in the Bay to finally bench him.”

Rodriguez testified that he wrote the message. The “committee,” which he said was made up of three Mexican Mafia members at Pelican Bay — Gabriel “Sleepy” Huerta, Henry “Indio” Carlos and Roland Berry — had the “final say-so” on Estrada’s fate, Rodriguez said.

Subscribers get exclusive access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers special access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Explore more Subscriber Exclusive content.

Prosecutors noted to the jury that less than two weeks before the date referenced in the message, Chavez had gone to Pelican Bay to meet with 10 Mexican Mafia members, including Berry and Huerta.

Chavez testified that he had legitimate reasons to consult with all of them. Berry was seeking to be resentenced, he said, and Huerta had an upcoming parole hearing and a pending appeal. Berry, Huerta and Carlos have all denied being members of the Mexican Mafia at parole hearings.

Chavez denied any role in the campaign against Estrada. In a power struggle like that, “there’s going to be people that are dead,” he testified. “One side’s going to lose.”

His attorney asked what might have happened if he’d been caught in the middle. “You’re done,” he said. “You’re dead. And if you’re lucky it’s just you, not anyone around you.”

Jean Pierre Espino, an investigator at ADX-Florence, a maximum-security penitentiary in Colorado, was monitoring a live feed of a legal visit when he saw something “abnormal.”

The visit itself was curious, Espino testified. On May 14, 2015, Chavez had traveled to the prison, which is home to 380 terrorists, spies, drug-trafficking kingpins, escape artists and inmates who have killed behind bars. They are held in solitary cells that measure 12 by 5 feet and moved every three months “to avoid them getting comfortable,” Espino testified.

Inmates are allowed four 15-minute phone calls a month to family or friends. A prosecutor asked if the penitentiary was designed to limit an inmate’s ability to communicate. “Absolutely,” he said.

Espino was watching through a soundless video feed as, one after the other, four reputed Mexican Mafia members shuffled into a visiting booth reserved for attorneys with their wrists shackled to their waists and dressed in white jumpsuits. Each man met with Chavez for about an hour.

The footage showed Chavez scribbling on a legal pad, passing the papers through a slot or holding them up to the glass partition for the inmates to see.

After conferring with Francisco “Puppet” Martinez, whom law enforcement officials consider the longtime boss of the 18th Street gang in Los Angeles, Chavez went to the restroom for what struck Espino as an “abnormal” length of time. After the lawyer walked out, Espino went in.

Inside a toilet, Espino said he found three scraps of paper, soaked in urine. Written on them were names of gangs — “V13,” “Brats Bellflower,” “Rockwood” — and Mexican Mafia members — “Tablas F-13,” “T-Wilmas,” “Wizard F-13.”

Prosecutors did not tie the notes to any particular conspiracy at trial, but offered them as evidence that Chavez was carrying gang communications in and out of the maximum-security prison.

The footage showed Chavez scribbling on a legal pad, passing the papers through a slot or holding them up to the glass partition for the inmates to see.

Chavez said he’d taken notes while talking to Martinez, whom he represented in “administrative matters” associated with his confinement at ADX-Florence.

The lawyer said he didn’t understand what Martinez was telling him but knew enough to suspect it was “illicit.” He went to the bathroom intending to get rid of the notes, but “I was just so nervous that I didn’t flush,” he testified.

Of all the gang members that prosecutors called to the witness stand, Raul “Cool Cat” Rocha was a curious choice.

He admitted trying to kill Chavez.

A member of the Azusa-13 gang since he was 11, Rocha first heard of the lawyer in Pelican Bay’s security housing unit, where he spent 15 years in one-man cells with “no windows, no nothing,” he recalled. All he saw of the outside world, he said, was a patch of sky through a mesh screen in the cage where he exercised alone.

Rocha was held for a time in the same pod of cells as Ruiz, who told him Chavez might be able to challenge his sentence. By then, Rocha had been in prison nearly two decades for a third strike — stealing a pair of pants in 1995.

Ruiz assured him that the lawyer “could be trusted,” so after paying him $2,500 to take his case, Rocha testified that he began sending messages to Chavez’s office that contained keys needed to decipher other coded communications. He said he mailed the notes in envelopes marked as confidential legal material to ensure prison officials wouldn’t read them.

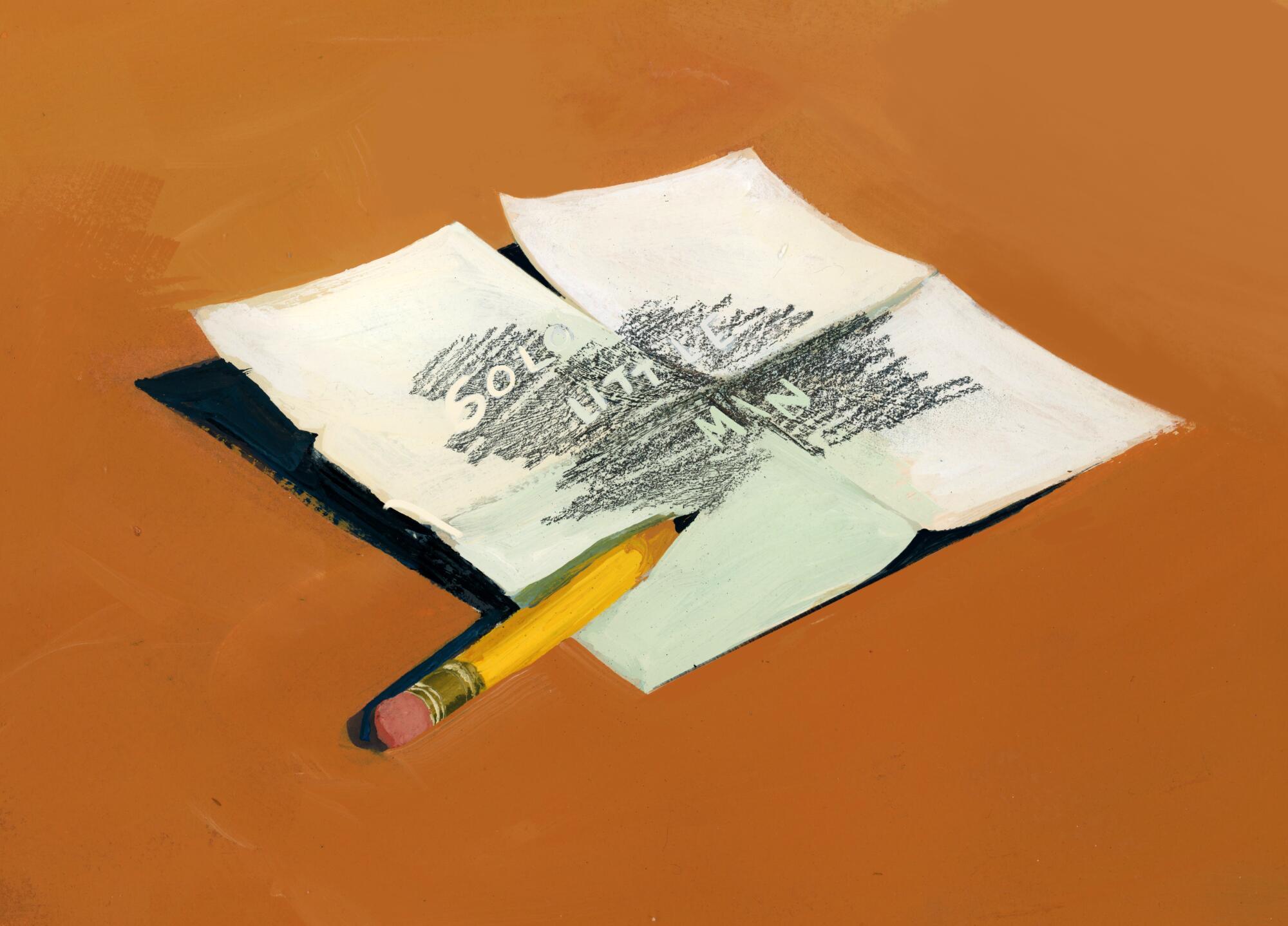

Rocha once received what he called a “ghost note” from Chavez, he testified. It looked like a blank sheet of paper, but when he rubbed pencil lead over it, two names appeared: Solo and Little Man, he said. Not knowing their significance, Rocha said he passed the names on to two Mexican Mafia members at Pelican Bay.

The names surfaced again when Rocha was brought down to Los Angeles County jail for a court hearing. Robert “Dopey” Hinojos, a Mexican Mafia member held a few cells down from him, asked Rocha to give his lawyer a note, Rocha testified. Hinojos wanted to know whether Solo and Little Man were “on the lista” — a list of people the Mexican Mafia wanted dead.

Robert Hinojos was convicted after a trial that shed light on the workings of the Mexican Mafia, a group of about 140 men who wield enormous influence in prisons and on the streets of Southern California.

Rocha said he slipped the message to Chavez in the jail’s visiting room. Chavez confirmed Solo and Little Man were marked men, then swallowed the note, Rocha said.

Chavez denied confirming that anyone was on a hit list. “I did not, and would not, ever harm someone,” he testified.

Solo was Dominick Gonzales, a Mexican Mafia member from Pacoima. He’d been gunned down in Bassett a few months earlier. Little Man was Frank Munoz, a Mexican Mafia member from Wilmington. He would be killed in Hawaiian Gardens a month later.

Rocha testified that Chavez asked him to carry back to prison a letter from Landa-Rodriguez, the Mexican Mafia member who had once controlled the L.A. County jails. He was to deliver it to Richard “Psycho” Aguirre, a reputed Mexican Mafia member, Rocha said.

Rocha once received what he called a “ghost note” from Chavez, he testified. It looked like a blank sheet of paper, but when he rubbed pencil lead over it, two names appeared: Solo and Little Man, he said.

Landa-Rodriguez had lost control of the jails after being accused of sanctioning the murder of Aguirre’s nephew, Rocha said. The letter was his attempt “to plead his case,” an FBI agent testified.

Aguirre, who has been serving 15 years to life for murder since 1981, has denied being a member of the Mexican Mafia before the parole board. Chavez represented Aguirre at a hearing in 2014, submitting a letter that promised Aguirre a job as a busboy or dishwasher at his family’s restaurant, should he be released.

An inmate slipped Rocha the two-page letter, which he said he secreted in his rectum for the trip back to High Desert State Prison in Susanville.

Aguirre was furious at Chavez for helping Landa-Rodriguez, Rocha testified. The lawyer “was getting too big for his britches,” he recalled Aguirre saying, going from prison to prison “thinking he was somebody he wasn’t,” asking “too many questions about the wrong people.”

Rocha said Aguirre asked him to kill Chavez. He was upset at being asked to commit such a brazen crime when he had a chance to get out after two decades in prison, but he agreed to do it, he said.

They decided the only way to do it was to stab Chavez in the courtroom, Rocha said. He explained to Aguirre and another Mexican Mafia member involved in the plan that his feet would be chained to the floor and only one hand would be unshackled. “I wanted to clarify to them that if I did come across to do it, I’d try my best,” he testified.

When Rocha returned to Los Angeles for a hearing, he obtained a shank in the county jail and sneaked it into the courtroom in his rectum, he said. For reasons he never understood, his lawyer didn’t show up.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.