Zaha Hadid, world-renowned architect, is dead at 65

Even by starchitect standards, Zaha Hadid was a force of nature with an outsized personality.

The celebrated Iraqi-born British architect — the first woman to win the Pritzker Prize, architecture’s highest honor — cut short a BBC radio interview last year when the line of questioning turned toward a sensitive subject: her 2020 Tokyo Olympic Games stadium design, scrapped because of spiraling costs.

“Don’t ask me a question when you can’t let me finish it,” Hadid said. “Let’s stop this conversation right now.”

That boldness, reflected brightly in striking buildings that punctuate cities around the world, is what the architecture world remembered Thursday after Hadid died at age 65. She suffered a heart attack Thursday morning while being treated for bronchitis in a Miami hospital, according to her London-based firm.

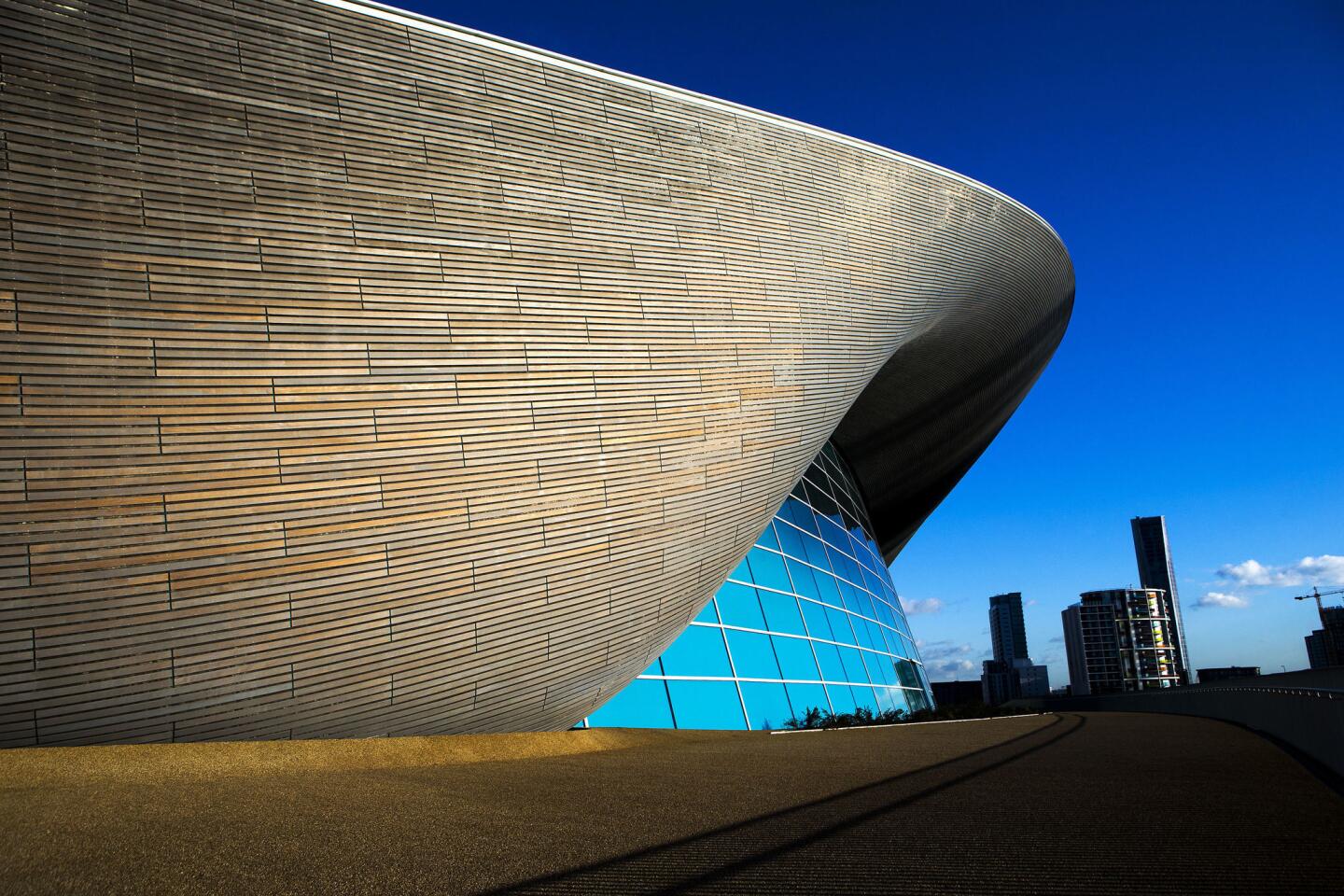

Hadid made her mark with buildings such as London Aquatics Centre, which served as a venue for the 2012 Summer Olympic Games, as well as the MAXXI museum for contemporary art in Rome and the innovative Bridge Pavilion in Zaragoza, Spain.

In the U.S. she designed the Lois & Richard Rosenthal Center for Contemporary Art in Cincinnati and the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum at Michigan State University, a modestly sized but architecturally daring building of unconventional angles that opened in 2012.

“She is without question one of the great architects of our time,” Eli Broad said in a statement. “We will miss our friend, and the world will miss the many innovative and cutting-edge projects she had yet to imagine.”

When Hadid received the Pritzker in 2004, the jury cited her “commitment to modernism,” as well as her skill in “creating an architectural idiom like no other.”

Her designs often made powerful visual statements, fusing the modern with the avant-garde. She was dubbed the “Queen of the Curve” for buildings that eschewed hard angles and corners.

Her international cachet was stratospheric, but her career was not without controversy. One of her most significant projects in recent years was the Al Wakrah Stadium in Qatar, a sports center that will serve as a venue for the 2022 World Cup.

In 2014, Hadid sued the New York Review of Books over an article that alleged deaths of construction workers on the project. Hadid vehemently denied the allegations, and the publication later issued a correction and apology, but the architect still faced criticism for saying it wasn’t her job to worry about working conditions. The stadium design also was mocked by some for resembling female genitalia.

“It’s really embarrassing that they come up with nonsense like this,” she told Time magazine in 2013.

Hadid spoke her mind and didn’t filter her displeasure, sometimes to the detriment of her public image. The media often portrayed her as an abrasive, jet-set diva, but in person Hadid was different, said Anissa Helou, the Lebanese-born chef and author who knew the architect since their youth.

Zaha Hadid in 2009 outside her Riverside Museum in Glasgow, Scotland. Hadid, the first woman to win the Pritzker Prize, architecture’s highest honor, has died at age 65.

“She never forgot her old friends,” Helou said. “Her success never spoiled her. She has a reputation for being difficult, but she was very loyal and true.”

With her tempestuous spirit came a healthy dose of self-awareness.

“I can be my own worst enemy,” she told the Guardian. “As a woman, I’m expected to want everything to be nice, and to be nice myself.”

Born in Baghdad in 1950 to a well-to-do family — her father was a leader of Iraq’s National Democratic Party and advocated for democratic reforms — Hadid attended school abroad and studied mathematics at the American University of Beirut. She began her formal pursuit of architecture in 1972 at the Architectural Assn. in London, where she was a student of Rem Koolhaas.

She began her own practice in London in the late 1970s and gained attention for her theoretical work.

Some of her earliest concepts were never realized, partly because of their avant-garde nature. They included the Peak, a private club in Hong Kong that integrated new structures on the hills of Kowloon, and a design for the Cardiff Bay Opera House in Wales that faced resistance from some local politicians.

Her later successes included the Guangzhou Opera House in China, which opened in 2010, and the Heydar Aliyev Center in Azerbaijan in 2013.

The architect didn’t focus solely on prestige buildings. Her firm worked on myriad smaller projects including a ski jump in Innsbruck, Austria, and the set for Mozart’s “Cosi fan Tutte” performed at Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles in 2014.

In 2006, she received a retrospective exhibition at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York.

Hadid wasn’t married and did not have children. Her survivors include her brother, Haytham. Another brother, Foulath, died in 2012.

“I have not sacrificed my private life,” she told the Guardian in 2008. “I don’t think one has to get married. Nor are you obliged to have children if you don’t want them.”

Hadid’s honors include being made a dame of the British Empire in 2012. Earlier this year, she received the Royal Gold Medal from the Royal Institute of British Architects, making her the first woman to win the prestigious award on her own.

“There is still a stigma against women,” she told the Architect’s Journal afterward. “It has changed a lot — 30 years ago people thought women couldn’t make a building. That idea has now gone.”

MORE:

Architect Zaha Hadid becomes first woman to win Pritzker Prize

A mix of the urban and urbane: Zaha Hadid’s remarkable Cincinnati Contemporary Arts Center

Zaha Hadid’s garden spot in Germany has city smarts

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.