Newsletter

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Here are some of the memorable characters introduced to Times readers in 2021. Among them: a feminist witch, a trailblazing Black journalist, a loving brother and the wife of a far-right extremist.

Looking back at the Capitol riot, Tasha Adams ponders her time as an Oath Keeper’s wife and asks: “What if I had not supported him?”

“Him” is her estranged husband, Stewart Rhodes, founder and leader of the Oath Keepers, an anti-government group whose members stand accused by federal authorities of having played a crucial role in the Jan. 6 insurrection. During nearly 23 years of marriage, Adams says she devoted herself to Rhodes’ aspirations. She worked as an exotic dancer to help put him through college, assisted in writing his papers and encouraged him to successfully apply to Yale Law School. When he was looking for direction in life — a cause — Adams helped him start the Oath Keepers.

Guthrie Castle, in the golfing heartland of Angus, Scotland, is Dan Peña’s home. And when he’s not delivering blistering lectures, the graying Peña lives a relatively quiet Scottish-laird existence.

It’s all so improbable. Peña seemed bound for failure through his difficult youth in East Los Angeles and the San Fernando Valley until he did something Americans do best. He reinvented himself.

For years, Zachary Horwitz lured people into what federal investigators describe as one of the most audacious Ponzi schemes in Hollywood history.

The alleged scam opened a money spigot that enabled the low-level actor to live like a studio boss in a lavish Westside home with a screening room, prosecutors say. Horwitz traveled by private jet.

His April 6 arrest on a fraud charge followed a century-old Hollywood tradition of accused swindlers running get-rich-quick schemes that exploit investors’ attraction to the glamour of a movie business they know little about.

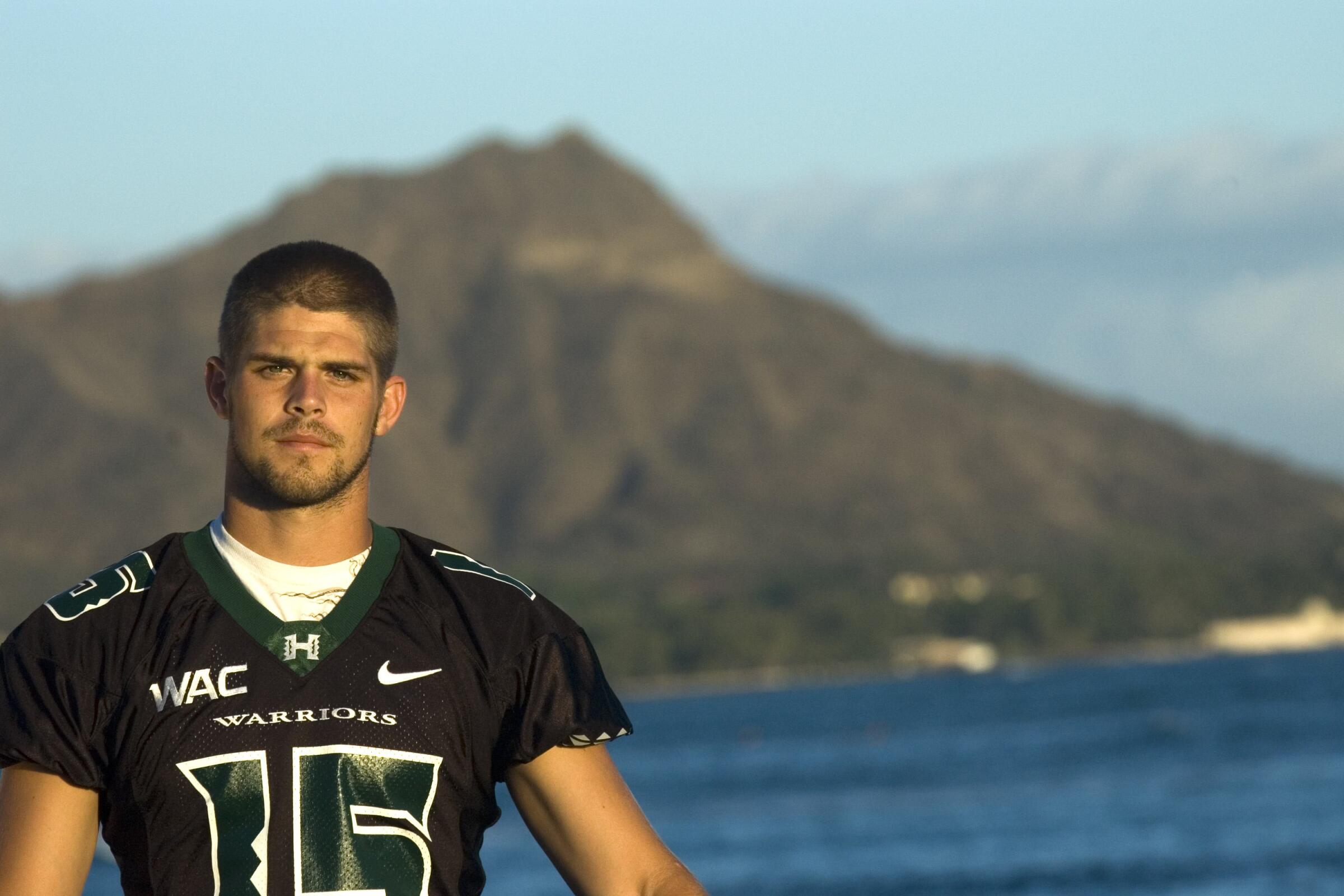

When Terry and Betsy returned home, they were stunned to find their son there, in the family room, empty beer cans and two vodka bottles nearby. Colt Brennan had left the live-in treatment center where he was four months into the five-month substance-abuse treatment program. He had, as his father would later say, “returned to the dark side.”

After a rainbow-brilliant three years at the University of Hawaii and an NFL career that fizzled, Brennan’s existence became a series of failed starts to rediscover peace and chase away his tormentors.

Now, they were back, and what followed were roughly 12 chaotic, frustrating and bewildering hours that would end Brennan’s struggle and his 37 years of life, leaving those around him to ponder how a kid who produced so much magic in paradise died as a grown man going through hell.

For 50 years, Zsuzsanna Budapest dedicated much of her life to creating and disseminating Dianic Wicca, a feminist, Goddess-centered spirituality she originated in Los Angeles in the 1970s.

She founded the all-women Susan B. Anthony Coven No. 1 and was arrested on suspicion of reading tarot cards in Venice when divination was still illegal across most of California. She publicly hexed murderers and rapists, wrote 13 books on ritual and witchcraft and founded the long-running International Goddess Festival.

Outside witchy circles, Budapest remains relatively unknown, but she has been a pioneering, though sometimes divisive, force in a state famous for fostering unorthodox forms of spirituality and belief.

It was a 189-word obituary titled “A Special Sister.” The grief was palpable. So was the love.

Karen Ann Sydow died Sept. 5 at the age of 61, and two days after her death, her brother, Erik Sydow, began sketching out a written tribute.

What Erik wrote captured his sister’s essence. It also felt universal, so Times reporter Daniel Miller took a picture of the obituary and shared it on Twitter. The discourse there often descends into the cynical and shrill, but Erik’s remembrance struck a chord. Before long, thousands of people, some typing through tears, had shared condolences, from anonymous users to major TV personalities.

Erik had no idea that his tribute was widely shared, and he was touched by the outpouring of support. But he was more interested in talking about his little sister.

In the early 1980s, José Zelaya would seek refuge from El Salvador’s agonizing civil war in the oasis of his imagination. His favorite TV shows were Disney programs, and before he had started kindergarten he was drawing startlingly accurate likenesses of the world’s most recognizable cartoon rodent, along with fanciful creatures modeled on the real fauna and flora that surrounded his home.

Today, as the only native Salvadoran graphic artist and character designer working for Disney Television Animation, Zelaya remembers the colors of the birds, animals and plants of his homeland, the mauves and fuchsias and emerald greens that infuse his work on animated series such as “The Lion Guard” and “Jake and the Never Land Pirates,” and such films as “George of the Jungle” and “Lilo & Stitch.”

In the now almost vanished country that existed before the war, he learned the ways of rabbits and birds, snakes and goldfish and water-skipping basilisk lizards that inhabited the hills and forests around Soyapango, then a largely rural suburb of the capital, San Salvador.

At Disney, his bosses and colleagues agree that Zelaya is a rarity in their world: a self-taught genius.

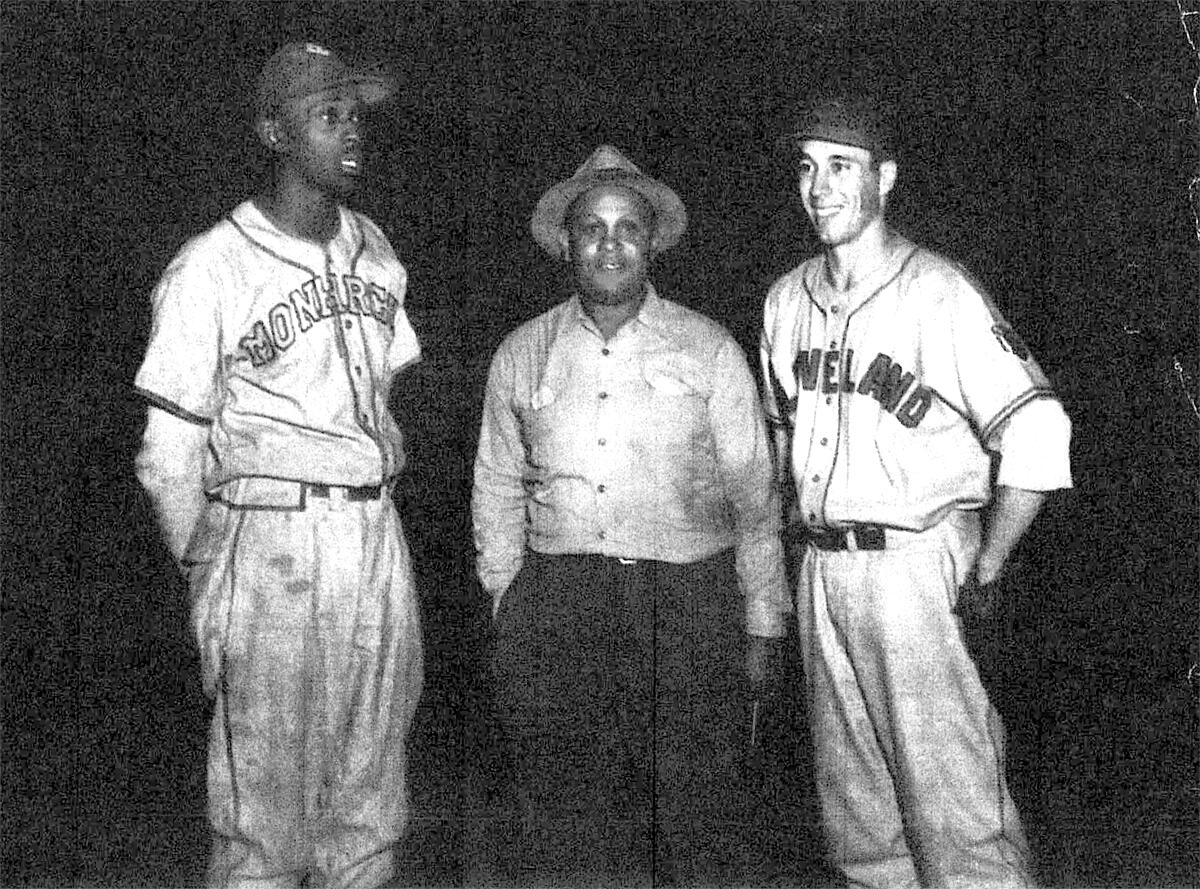

Mornings like April 17, 1943, the day before the Pacific Coast League season opened at Wrigley Field, can be easy to overlook in the decades-long struggle for civil rights. What happened wasn’t Bloody Sunday at the Edmund Pettus Bridge or Rosa Parks refusing to move to the back of a bus, but instead one of innumerable smaller struggles amid the larger movement. As the country works through another era of racial reckoning, these unheralded moments, these forgotten trailblazers matter too. They should be remembered.

Though Halley Harding’s fights, small and large, have faded into history, his impact hasn’t. He led the effort to reintegrate the NFL and helped set the stage for Jackie Robinson to become the first Black player in the modern era of major league baseball. Harding had an unflinching, unrelenting, almost prophetic certainty that those barriers — and so many others — would be obliterated.

Within the world of casino experts and magicians, Steve Forte handles a deck of playing cards the way Roger Federer wields a tennis racket. Not just among the best, but the best, full stop. In his hands, cards appear to shuffle but remain in perfect order. Cards apparently dealt from the top of the deck are taken invisibly from the bottom.

After years of being a reclusive figure, the 65-year-old Forte has published “Gambling Sleight of Hand,” his life’s work of underground card moves in a two-volume book of nearly 1,100 pages.

For nearly two decades, U.S. District Judge Roger T. Benitez was a low-profile jurist handling routine immigration and drug cases in San Diego federal court.

Then, in three consecutive years, the judge made a trio of rulings that have upended California’s gun laws and launched him into the intensifying national debate over guns.

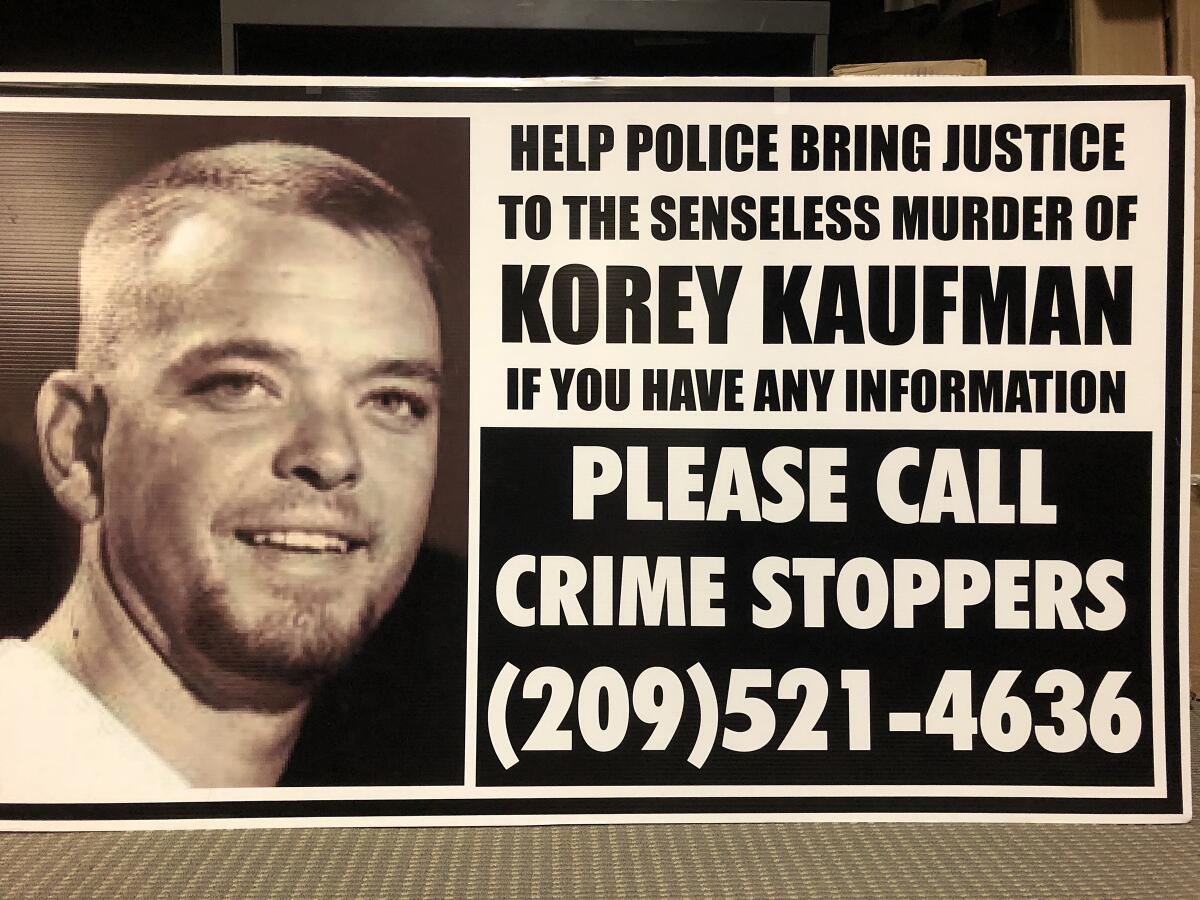

A team of heavily armed SWAT officers, rifles aimed, converged on Frank Carson that morning in the driveway of his Turlock home. He was, the law had decided, a dangerous man, the kingpin of a murder conspiracy, and so they would take no chances with the shambling, heavyset 61-year-old criminal defense attorney, who sneered at them defiantly as they clapped handcuffs behind his back.

Carson knew what came next. They saddled you with the mug shot that would haunt you forever, looking grim and guilty and defeated. “All I wanted was not to look subservient and crawl like a dog,” he would say, “which is what they intended.”

And so as the camera clicked, Carson put on a carefree, open-mouthed smile, his eyebrows aloft in happy surprise above his thick glasses. Far from a first-degree murder defendant facing life in prison, he looked like a bumpkin who had won a new tractor. It was, a prosecutor would say, the same “good old folksy country boy” facade he had used to fool so many juries about his real nature.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.