As a boy, even when the Salvadoran army was laying waste to his hometown and guerrilla rebels were stalking the nearby woods, José Zelaya held fast to his dream.

“One day,” he told his mother, “I’m going to work for Mickey Mouse.”

The vow took Degni Menéndez by surprise. At the time, her 4-year-old son could neither read nor write.

“God fulfills dreams,” she told him. “You have to go to school first and push yourself, and pay attention to everything your teachers tell you.”

In the early 1980s, Zelaya would seek refuge from El Salvador’s agonizing civil war in the oasis of his imagination. His favorite TV shows were Disney programs, and before he had started kindergarten he was drawing startlingly accurate likenesses of the world’s most recognizable cartoon rodent, along with fanciful creatures modeled on the real fauna and flora that surrounded his home.

Drawing was always a way for me to grasp another world that I controlled.

— José Zelaya

Today, as the only native Salvadoran graphic artist and character designer working for Disney Television Animation, Zelaya, 45, remembers the colors of the birds, animals and plants of his homeland, the mauves and fuchsias and emerald greens that infuse his work on animated series like “The Lion Guard” and “Jake and the Never Land Pirates,” and such films as “George of the Jungle” and “Lilo & Stitch.”

In the now almost vanished country that existed before the war, he learned the ways of rabbits and birds, snakes and goldfish and water-skipping basilisk lizards that inhabited the hills and forests around Soyapango, then a largely rural suburb of the capital, San Salvador.

“I have touched them, I have not only seen them in photos,” Zelaya said of his mental bestiary, as he flipped through an iPad of drawings at a restaurant in North Hollywood. “Those are the things from my childhood that I lived in El Salvador that have stayed with me. That’s why I love drawing animals.”

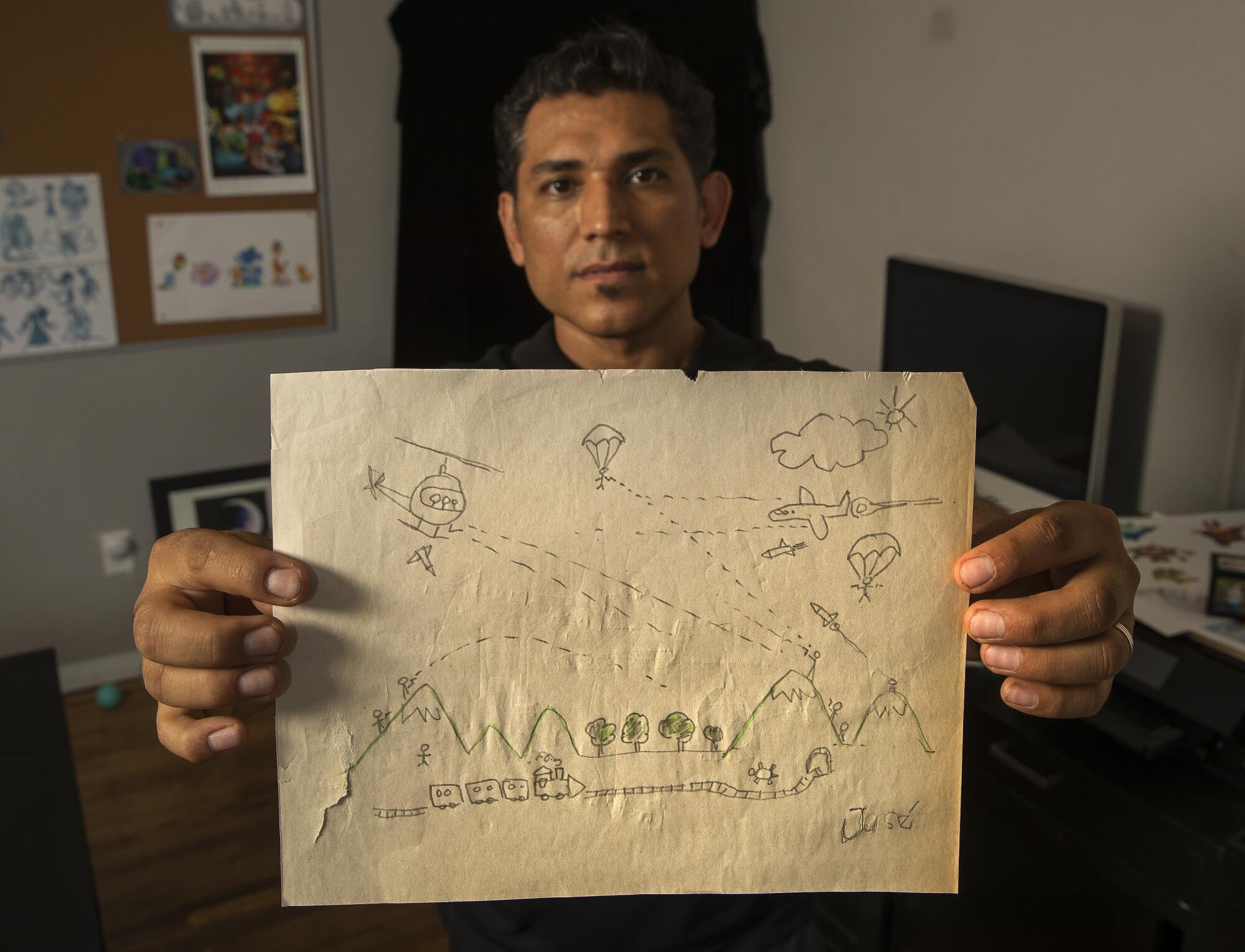

There were other drawings from that time, and they were far more harrowing: of the bombers and helicopters he’d seen strafing entire neighborhoods, of soldiers spraying bullets at the insurgents and the insurgents firing back.

“Everyone killed each other in my drawings.”

For a boy with a singular talent, drawing was both traumatic and cathartic, a way of taming reality while retreating from it.

“Drawing,” he said, “was always a way for me to grasp another world that I controlled.”

At Disney, his bosses and colleagues agree that Zelaya is a rarity in their world: a self-taught genius.

“He’s one of the most naturally talented character designers I ever met, naturally gifted,” said Phil Weinstein, a Disney producer who has worked alongside Zelaya for the past decade. “He is able to capture not only that kind of metric representation of volume on the character, but also that charm and appeal that exist in all Disney characters.”

Creativity ran in the family. His father, a cartoonist who drew landscapes as a hobby, designed jewelry.

One of Zelaya’s uncles also was a talented artist. A cousin was a clothing designer.

“I feel like art is in our family genes.”

During his youth, Zelaya’s parents were too poor to pay for art classes. But his mother bought him notebooks for drawing and would scrape together bus fare so that he could compete in drawing contests. By age 6 he was reimaging more muscularized knockoffs of characters from “The Smurfs,” “Tom & Jerry,” “Mazinger Z” and “He-Man.”

The results were hit and miss. “I was trying — they didn’t work out for me,” he said with a laugh.

He took apart toys and arranged the pieces according to his fancy. He drew faces and bent pop-culture archetypes to his own invention. He also learned how people he knew — not just plants and animals — could influence his art.

In his first Disney show, “Recess” in 1997, he was responsible for bringing to life the tough-talking but charming Ashley Spinelli, a characterization inspired by a friend, Mara Ancheta, who was a former partner at a Santa Monica animation studio.

“The first time I met Mara she had a leather jacket, some Harley-Davidson boots, just like Spinelli,” Zelaya recalled. “She was small, very strong, friendly, outgoing, funny. That’s why the color of her personality stuck in my mind.”

Another character, a mama bear in the TV series “Mickey and the Roadster Racers,” embodies a person even nearer and dearer to him.

“I definitely thought of my mom — even though she’s a bear! You can see it in her eyes, in the tenderness. I made her hair the color of coffee, like my mother’s.”

“I took it from the love that my mom always gave me, like a mama bear,” Zelaya continued. “When I design characters, I often look at people’s characteristics. When the character feels more real, people identify more.”

As a Disney illustrator, Zelaya belongs to a community of artists, a surrogate family of creatives. In El Salvador, he and his family watched their community — their entire world — slowly implode.

On one occasion the family locked themselves inside their house to take shelter from a raging gun battle. Zelaya and his brother began to cry because they’d left their toys behind. To comfort her boys, their mother raced outside to collect the toys, risking her life.

Another time, government troops captured a young guerrilla fighter and shot him in front of the family home before dragging the body away. The soldiers ordered Zelaya’s mother and a neighbor to clean up the blood.

“That night I dreamed of his face,” Zelaya said.

Zelaya’s father lived with his family until the boy was 6, then disappeared. Father and son wouldn’t meet again for 11 years, when they reunited in Los Angeles. (Zelaya’s father died in 2012.)

Meanwhile, in the middle of the 12-year war, in 1986, Menéndez decided to emigrate to the United States, convinced that in Los Angeles her son might have a shot at working at Disney in some distant, improbable future. A year and a half later, her three children joined her in the San Fernando Valley.

“I knew he was not going to achieve that dream there,” Menéndez said.

As a child, Zelaya always felt confident of his talent. But upon settling in North Hollywood, his self-esteem quickly fell apart.

The 12-year-old began to see the harsh reality of California, where his mother, who worked as a babysitter and housecleaner, had to recycle cans to make ends meet. Zelaya, meanwhile, struggled to master a new language.

“I felt less, I felt isolated,” he said.

Gangs rambled through their neighborhood. Drive-by shootings were routine.

“I remember that gang members were my friends, because they knew that I drew well and I drew them, their names, and they liked it,” he said. “They beat up others, but never me, they kind of gave me respect, because I knew how to draw. Having that side of being an artist helped me not to be bullied. Art saved me.”

Along with his steadfast mother, he drew crucial support from one of his teachers, Karen Worle, at Francis Polytechnic High School in Sun Valley. She cared about his academic development and encouraged him to enter drawing contests.

“At a time when I didn’t believe in myself, there was always someone who believed in me,” he said.

Because Zelaya was so obviously gifted, yet labored with English, his teachers sometimes let him make a cartoon to express his ideas rather than write an essay.

In 1994, when Zelaya was a senior, a filmmaker named Bruce Royer visited the school to teach a two-day animation workshop.

“I saw this young man who had unbelievable ability to draw,” said Royer, a veteran producer of documentaries and educational shorts. In conversing with the boy, he discovered that Zelaya had developed that ability on his own.

“He definitely in the area of design and draw is the most naturally talented I have ever met, even 25 years later,” Royer said.

El Salvador’s Legislative Assembly has approved legislation making the cryptocurrency bitcoin legal tender in the country, the first nation to do so.

The filmmaker brought Zelaya to AnimAction, a vocational training center in Santa Monica. The annual cost was $20,000; Zelaya was awarded a full scholarship.

“Bruce was the angel and the guardian of us,” Menéndez said.

Working with A-list professional animators, including Edwin Aguilar, Alex Ruiz, Raymond Persi and Jeremy Robinson, he took animation, human figure, Photoshop, psychology and three-dimensional design classes.

“I wanted to have a career where I was going to be able to get ahead. I didn’t know art was going to give me something to eat,” Zelaya said.

But, once again, mother knew best.

“My mom told me, ‘Pick something you like because you’re going to do it for the rest of your life.’”

After the yearlong training, Royer hired Zelaya as an instructor for another 12 months. Before 1996 ended, a recruiter from Disney had asked to see the young man’s portfolio and, impressed, invited Zelaya to come for an office visit the next day.

Soon after, Zelaya called his mother with news, using the language of his Salvadoran childhood: “Mommy, I’m going to work for Mickey Mouse.”

Over the years, Weinstein said, he has come to appreciate not only Zelaya’s God-given ability but his nuanced and intuitive grasp of the varieties of Latin American culture.

“He really understands those cultures so well that he could give us designs that authentically represent those regions,” said the Disney producer. “That is incredibly helpful.”

Zelaya thinks he’s been able to fit in at Disney because he has a chameleon-like ability to adjust his personal aesthetic to the company’s needs. Whenever he draws Latino characters, he strives to reflect the “picturesque colors” and to accurately depict the familiar body language, facial expressions, skin tones and mannerisms of his beloved native culture.

His art also incorporates subtle distinctions among the various countries and ethnicities of Latin America. For instance, in one episode of “Mickey and the Roadster Racers” involving a trip to Peru, he made sure that the llamas looked cartoonishly authentic, and that Mickey, Goofy and Donald Duck were garbed in appropriately Andean attire.

David Rodríguez, a color stylist who has worked at Disney since 1994 and adds the brilliant hues to Zelaya’s drawings, said his colleague “can adapt any style” while honoring each character’s cultural specificity.

A stretch of Salvadoran shoreline called Surf City is the location for the final qualifying rounds for surfing’s debut as an Olympic sport this summer.

“If it needs a character of Asian American, Hispanic American or African American [descent], José can adapt it through his art and not like a caricature, he can do it authentic without a stereotype,” he said.

Zelaya has become a mentor to other U.S.-born Latinos and Latin Americans aspiring toward careers in design and graphic arts. He has lectured in Colombia and Mexico, and via Zoom has inspired students from El Salvador to Australia.

His wife is from Australia, the daughter of Salvadoran immigrants. He and Elle Zelaya, 32, a graphic designer, met when she visited Los Angeles in 2008, and a long-distance relationship led to their marriage in 2015.

He advises students to reach out to veteran artists and to let their talents be known through social networking.

“If you know someone like me, send them an email, ask questions, they will answer you,” he tells them. “You don’t have to give up.”

That spirit of perseverance, Zelaya said, is something he had learned from his mother — and that, now, he needs more than ever.

Menéndez was interviewed in January before she contracted COVID-19. After a little more than three weeks fighting the virus, she died Feb. 17.

“She is my hero, my best friend, my greatest example to follow,” her son said. Long ago, she convinced him that he could wish upon a star. That knowledge keeps him aloft in this time of mourning, and through the memories of all he has witnessed and endured.

“The loss of my mother has changed me,” he said.

He wants to pay tribute to her in everything he does. He intends to transmit her values to his 1-year-old son, Levi. Perhaps some day Levi will watch one of his father’s cartoons and notice a mama bear with tender eyes and fur the color of coffee.

“The work that I do I put all my heart into it, what I have learned. Now, I am starting with more courage, enthusiasm and inspiration.” So said the man who works for Mickey Mouse.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.