Newsletter

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

These are among the tales of redemption, forgiveness and love told in Column One, The Times’ showcase for storytelling, in 2021.

Dr. Courtney Martin reached for her phone, opened the notes app to an empty screen and began to write.

I want to write about Karl. This is a long essay, but it’s because I love to write. Perhaps it’s my therapy, and perhaps it’s because Karl deserves to be noticed. Every hospital has a Karl.

Martin is the head of maternity services at Loma Linda University Medical Center, an accomplished physician and surgeon, a dynamic presence.

Karl is an all-but-invisible man. He works in the massive medical center’s dispatch department, wheeling patients from hospital rooms to radiology for MRIs and CT scans. He does not like attention. Martin, however, wants the world to know who Karl is and what he does. She calls him “this healthcare hero.”

Due to the pandemic, Karl became the person who moved the dead bodies from the rooms, then took them to the morgue. Maybe this was a job before the pandemic — I’m not sure. And, on the surface, this doesn’t seem that bad. But in a pandemic, Karl became the body collector.

Kept afloat by her orange life jacket and the bow of her family’s capsized boat, 9-year-old Desireé Rodriguez had watched helplessly as one family member after another let go of life.

Just as she, too, began to give up, the skipper of a commercial sportfishing boat spotted an orange smudge bobbing in the water through his binoculars. The crew radioed the Coast Guard, then transported the girl back to San Pedro, where medics wheeled her off the boat in a stretcher. That was the last time the rescuers and the girl saw one another. Until this year.

One evening last fall, Joseph Arriaga sat at his laptop and sent a Facebook message to a stranger.

So many of Arriaga’s defining memories had built toward this message. Arriaga was trying to sort out truth from family folklore, attempting to verify or disprove a story about his paternity — a story that had filled him with anger and shame for years.

“I’ve done a great deal of research,” he wrote, “and I think you might be my biological father.”

Other hikers could slip into autopilot as they struggled to reach the 14,505-foot summit. Jack Ryan Greener could not.

He had obsessed about this trail and this peak for 2½ years, ever since an accident left him paralyzed from the neck down, since he left the hospital on a gurney, since he wallowed in dark places, since he taught himself to walk again, since he pulled himself out of his trauma, visualizing over and over stepping onto the top of Whitney.

Pounding the terrain justified all the training, fear, pain, stress and tears.

But he had miscalculated.

Last spring, when the pandemic forced a global lockdown, Holocaust survivor Marion Ein Lewin wrote a moving piece for this newspaper, extolling the power of the human spirit and calling on everyone to summon their strength and resilience.

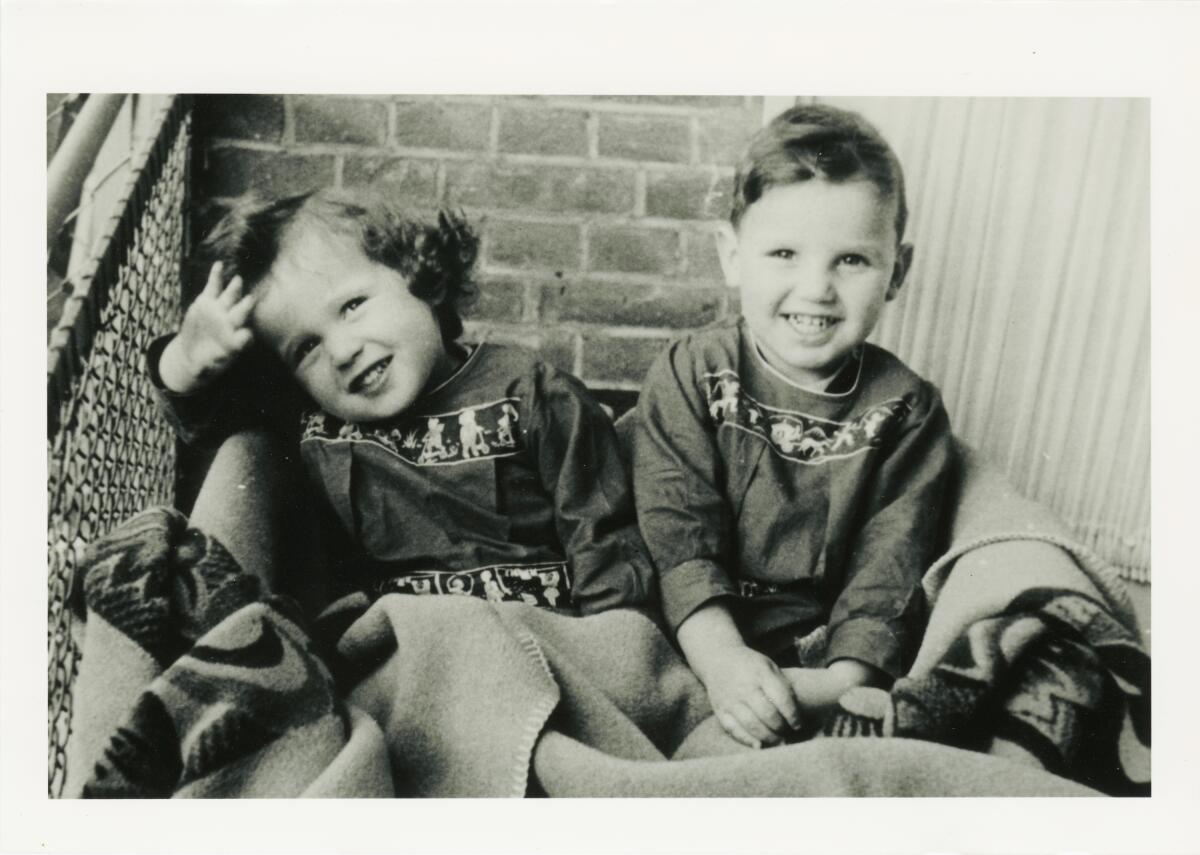

When Lewin offered the photo for use with her article, she and her brother — now 83 — could not have dreamed it would make its way back to the Netherlands. But it did, and 75 years after the liberation of Bergen-Belsen and the end of World War II, they were about to have some of the mysteries of their childhood unlocked.

Travelers on Interstate 15 east of Barstow might have a hard time imagining this region thousands of years ago, when bands of hunters roamed the edges of lakes and prowled grasslands in pursuit of bison, mammoth, horse and camel. Archaeologists have spent lifetimes trying to raise the past.

Fred E. Budinger Jr. has long championed the site’s antiquity. Bolstered by the opinion of the most esteemed archaeologist of the age, he enlisted other experts along the way. Most are dead, and he stands almost alone. Then, in April, came the letter from the federal Bureau of Land Management.

The bureau plans to fill all but five of the primary excavation pits. For Budinger, the bureau’s decision signaled the end of the most promising chapter in North American archaeology.

Nearly 29 years had passed when Trino Jimenez decided to write to the man who murdered his brother, prepared to never hear back.

The killing, in South Los Angeles, had been brutal. But Jimenez, a devout Christian, was ready to forgive Melvin Carroll.

“I can never forget him, but I am not consumed about an event that can never be undone,” he told Carroll in his February 2015 letter. “God loves you and even the crime of murder is a forgivable offense.”

Within a few weeks, he received a response.

To ward off the deadly virus that had invaded his small apartment, Jose Guadalupe Zubia slept in a surgical mask and cracked open a window beside his bed.

When his sons and daughters tested positive for COVID-19, Jose was the only one who tested negative. The children were determined to protect their diabetic father. But they lived crammed together in a one-bedroom apartment in South Los Angeles.

In South L.A., nearly 1 out of every 5 homes is overcrowded — typically defined as more than one person per room.

Nearly all their combined income went toward the rent. None of the children could afford to move out. So the Zubias had made do with an arrangement that was uncomfortable but tolerable — until the coronavirus hit.

For years, he had tried to handle the matters internally by writing memos to his bosses inside the Los Angeles County district attorney’s office, including Jackie Lacey, or filing grievances against supervisors he considered racist, according to district attorney’s office documents.

When that didn’t work, the prosecutor used the only weapon he thought he had left: his voice. In a dozen essays published on Medium under his pen name, he accused supervisors of refusing to confront law enforcement misconduct or pursuing cases against defendants he believed were obviously innocent.

His posts started to garner attention for intimately portraying the inner workings of the district attorney’s office, re-creating disturbing conversations among prosecutors and painting him as a hard-charging attorney seeking justice in the face of colleagues interested only in convictions.

For 18-year-old Chase Kirby, football felt like a ticket to a future beyond his remote town of 3,100 people deep in California’s northern forests. But after the COVID-19 pandemic shut down in-person classes, Chase half-heartedly finished his junior year, then went to work for the summer.

Rising before the sun, he left home one morning for a 5 a.m. shift at the local sawmill. It was hard, repetitive work. He liked it.

He was standing in front of a rotating conveyor belt when a few pieces of wood got stuck. He grabbed one just as the machine grabbed it, too. He didn’t have time to let go. In an instant, the machine had his arm and was yanking him forward.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.