Newsletter

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Times reporters usually observe from the sidelines, but sometimes they become part of the story. Ten Times staff writers share stories at once intimate and universal.

In our 23 years on the AT, as it’s known, our lives were ever-changing, but the trail always offered us familiar peace from the outside world — a walking meditation through the quiet forest shared with each other and the countless hikers we met.

Ours was a journey only made possible by sobriety, as both Dad and I struggled with alcohol dependence for many years. Then there was his cancer.

Fostering baby animals is hard, I won’t sugarcoat it. You may be awake much of the night handling feedings. There’ll be messes. You’re constantly watching to make sure the little one isn’t underfoot or in danger. But every little milestone — first feeding, first step, first poop — is a tiny act of grace in an otherwise jaded world.

“Fostering, especially with baby kittens, is an exciting and sometimes scary experience,” said Michelle Sathe, L.A.-based spokeswoman for Best Friends, a national nonprofit animal welfare group.

In Southern California, she told me, “there may be 10,000 or more dogs and cats looking for homes at any given time.”

I was driving cross-country to visit my friend who has a farmhouse in Maine.

She was dying. She told me I needed to accept that fact before I got there so we could get on with enjoying our visit.

I set a route that would carry me through wide open places and small towns. I was going to write about the parts of America I saw along the way. I worried I might be too raw, too unsettled, to try to understand the country stretching before me. Then I decided that was the right state of mind for a summer of vaccines, variants, disaster, division, reckoning, rage and floundering forward. I woke up on a Monday morning and headed east from Fresno.

A century from now, someone who has not yet been born will come to a haunting realization: Their life was shaped, in ways they may never fully understand, by the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020.

I know this, because it’s the story of my family.

It’s a story with unfathomable twists and turns, great pathos and heroism (not mine). It ends, like so many pandemic stories, with both heartache and humanity. And I have no doubt that versions of this mystery story exist in other families, though it’s entirely possible that they don’t know it and never will. There is no neat and simple end to a pandemic.

My 12-year-old son has always loved video games, but during the pandemic that love intensified. After hours of staring at a screen for Zoom school, he couldn’t wait to open his laptop again to play “Minecraft,” Roblox or “Pixel Gun 3D.” At the dinner table he often reported that the best thing that happened to him that day occurred in the virtual world.

To get him out of the house, we took walks in the evening. I’d ask if he’d heard from his friends. He’d talk about games. Did I think he should buy a military helicopter with missiles or a high-speed airplane in “Mad City”? The airplane was faster, but the helicopter would be more useful for breaking his friends out of jail.

Sometimes I let him keep talking while my mind wandered. Other times I asked if we could change the subject.

“Video games are pretty much the only thing that makes me happy right now,” he said one day.

That was a gut punch. I felt I had failed as a parent.

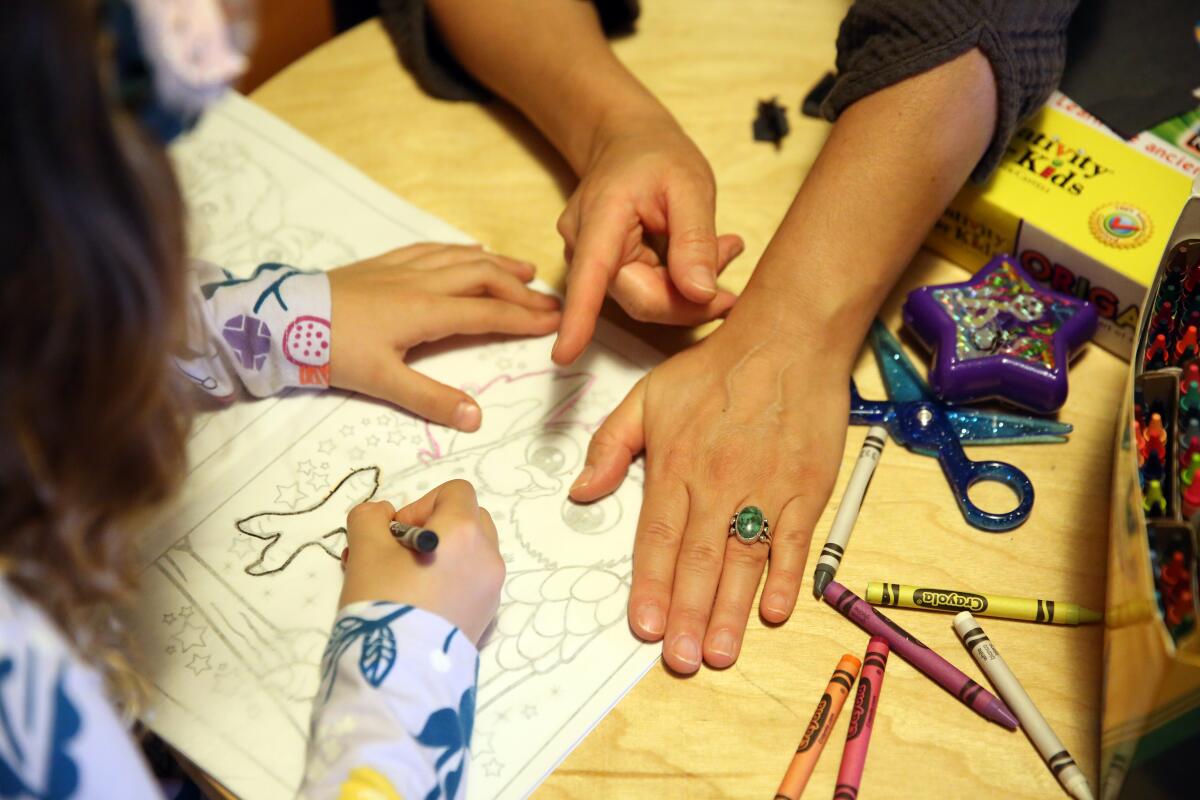

Cora became my shadow, following me around the house. At one point, she fell asleep in a ball behind my chair as I wrote a story on deadline. She hardly played in her room by herself anymore. When she did, she’d constantly call out just to check I was nearby: “Mom!”

Early on, I wondered what it would be like to establish a social pod to provide Cora the socialization she desperately needed.

I’d heard about families creating pods for their children — mostly for educational purposes. I’d read stories about pods and had seen some of my mom friends mention them on their Facebook feeds. But what was a pod? How do you form one? Was this even doable? I had so many questions.

We called it the “Cove,” the beach where I fished and bodysurfed and snorkeled and caroused with my brother, sister, cousins and friends.

Over the decades, this small stretch of dry sand became ever smaller, reduced by rising sea levels and by construction of one more massive beachfront home. At the highest tides, the dry sand is completely submerged. Still, the Cove endured, one of the California coast’s innumerable little gems.

Then, this May, the chain-link fence that had stood for decades suddenly disappeared. What is technically the westernmost end of La Costa Beach suddenly had its front door flung open to Pacific Coast Highway and, thus, the world.

The dear old Cove had been liberated! It feels clear that something has been gained. But was something lost as well? I wanted to find out how it happened and what it meant.

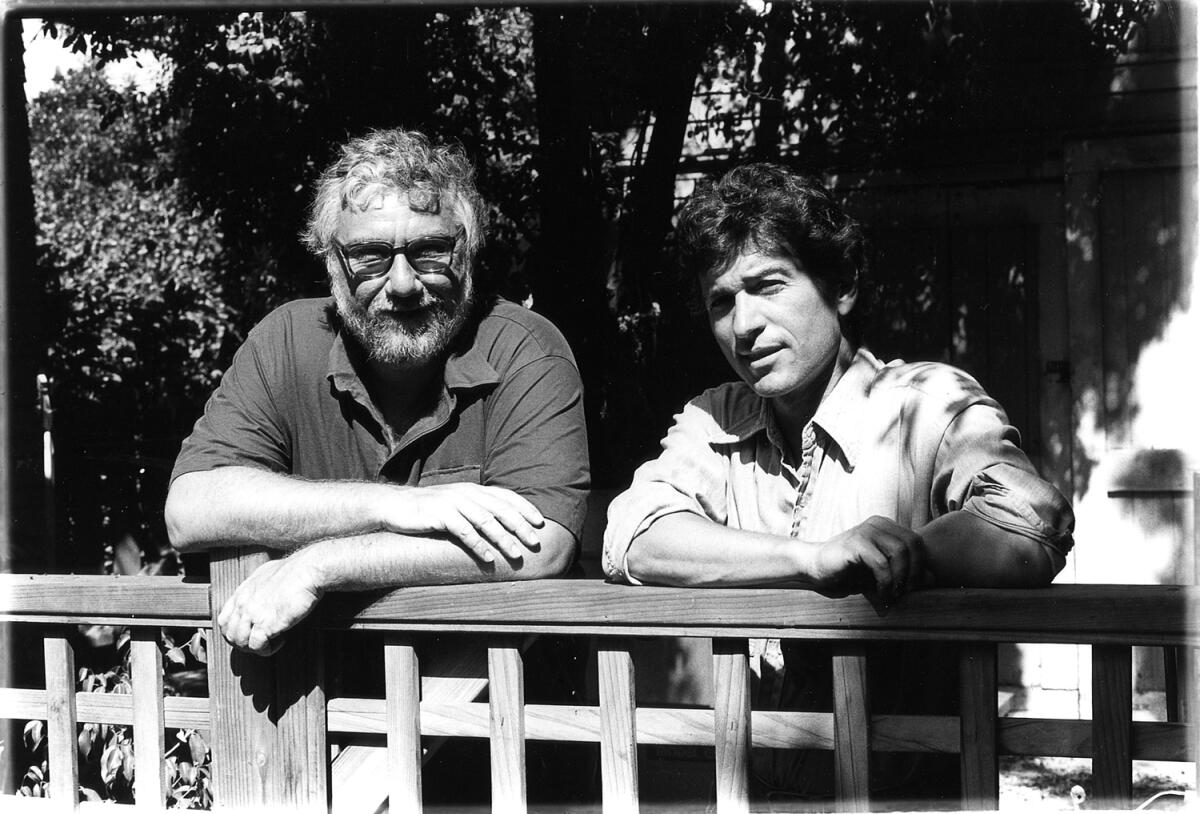

A Cal State Long Beach classroom, 1985 or so. Gerald Locklin looks every bit his nickname “Bear,” with bushy salt-and-pepper hair and beard, thick glasses, rumpled polo shirt, jeans and Birkenstocks with socks. He leans heavily on the lectern, and opens class the way he always did, asking in his Rochester accent, “What’s haaappening?”

He was one of the more important and prolific American poets of the last half-century, whose companionable approach to the mundane and the consequential mirrored his classroom style.

Locklin’s deceptively simple, witty writing helped shape and propagate a democratizing literature associated with the West Coast style.

As one of Locklin’s students back in the 1980s, I remember him as a singularly gifted teacher, an enduring friend and one of the brightest and funniest people I’ve ever met.

I had dealt with skepticism before. A week earlier, and five months before that, doctors had told me I was too emotional. I had overcome a case of COVID-19 in spring, and two doctors said there was no way I was still experiencing symptoms of the disease.

Across from my room at a Los Angeles hospital, patients were on ventilators. Tests showed that my heartbeat was indeed irregular and my oxygen low. My coronavirus test came back negative. The doctor thought I might be having issues with my heart and lungs. Or maybe there was another type of infection. I was released with some heart meds and told to see a cardiologist.

The next few months snowballed into 135 appointments. After seeing 32 doctors, going through 47 tests and seemingly countless blood draws, I learned there’s a term for me: I am a COVID-19 long hauler, and the experience has taught me much about myself, the medical system, the value of friends and family.

I’m not sure if I remember or if my mom later told me, but that night, when she got home, I thought she was a ghost because of the dust that coated her clothes and hair.

I am part of the tail end of the millennial generation, and belong to a select cohort who lived within a few miles of the two buildings that were once the tallest in the world. Twenty years on, I know the Sept. 11 attacks profoundly shaped me but I’m still sorting out how. And in this, I’m joined by many of my peers, who were children then and can see now, with the clarity of hindsight, that the attack by Al Qaeda changed the trajectory of their lives.

But, again: How?

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.