I tried to start a pandemic pod for my 5-year-old. Here’s how it went wrong

My 5-year-old started to resent her situation in late March, soon after the schools closed and after we barred play dates and trips to Chuck E. Cheese.

As the pandemic enveloped Southern California and Cora realized she wouldn’t see her friends for some time, her growing frustration manifested itself in misbehavior, picking fights and door slamming. I tried to be patient but failed more times than I’d care to admit.

Whenever Cora heard “coronavirus” on the radio, she would shout for us to turn it off.

“I hate the coronavirus!” she loudly declared.

Cora became my shadow, following me around the house. At one point, she fell asleep in a ball behind my chair as I wrote a story on deadline. She hardly played in her room by herself anymore. When she did, she’d constantly call out just to check I was nearby: “Mom!”

Early on, I wondered what it would be like to establish a social pod to provide Cora the socialization she desperately needed.

I’d heard about families creating pods for their children — mostly for educational purposes. I’d read stories about pods and had seen some of my mom friends mention them on their Facebook feeds. But what was a pod? How do you form one? Was this even doable? I had so many questions. I researched it.

A pod should be small — no larger than 10 people, some experts wrote. Others suggested drawing up a contract laying out the rules and guidelines. All agreed that trust was of the utmost importance. It all seemed so daunting and I had serious doubts.

“It’s just too risky,” I thought. The idea needed to marinate.

It wasn’t until summer when my sister — a physician — started a pod for her 11-year-old son with another family that I seriously considered the idea. My search for the right family would take me down a rabbit hole of awkwardness, rejection and frustration.

Since the coronavirus pandemic began, families have started social pods for their children. Did you start a social pod? If so, we want to hear about it.

But first, we had to get through the spring. My husband and I are lucky to work from home, but our jobs require a lot of concentration. Having Cora around while we worked seemed untenable.

Cora’s part-time caregiver, Carolina, runs a day care at her home that’s a 10-minute drive from us. We were blessed when she agreed to become Cora’s full-time nanny. With schools closed, her clients — mostly teachers at a local school — no longer needed her. Carolina was happy to care for just one child — thankfully, our Cora —and minimize her exposure.

Cora also attended preschool virtually from home once a week. The teacher tried her best to keep the students engaged, but Cora easily became distracted, then increasingly bored and frustrated. She began to argue, throw tantrums and slam the door to her room in protest.

I had a hunch that Cora’s growing misbehavior was normal given the stresses of the pandemic, but I needed some outside perspective.

“She is typical,” Laura Glynn, a Chapman University professor of psychology, told me. More than two-thirds of mothers reported an increase in problem behaviors in their preschool-age children since the pandemic started, according to a May survey that Glynn is part of at the Conte Center at UC Irvine.

“Ultimately, kids are resilient,” Glynn told me. “Ultimately, this is going to be a formative experience and time will reveal what the lasting impacts are, and that’s really going to depend on the age in which they experience this.”

One morning in late March, Cora said she no longer wanted to do “Zoom school.”

“It makes me too sad,” she declared, her lip quivering. “I don’t want to see my friends on the computer.”

We decided to pull her out.

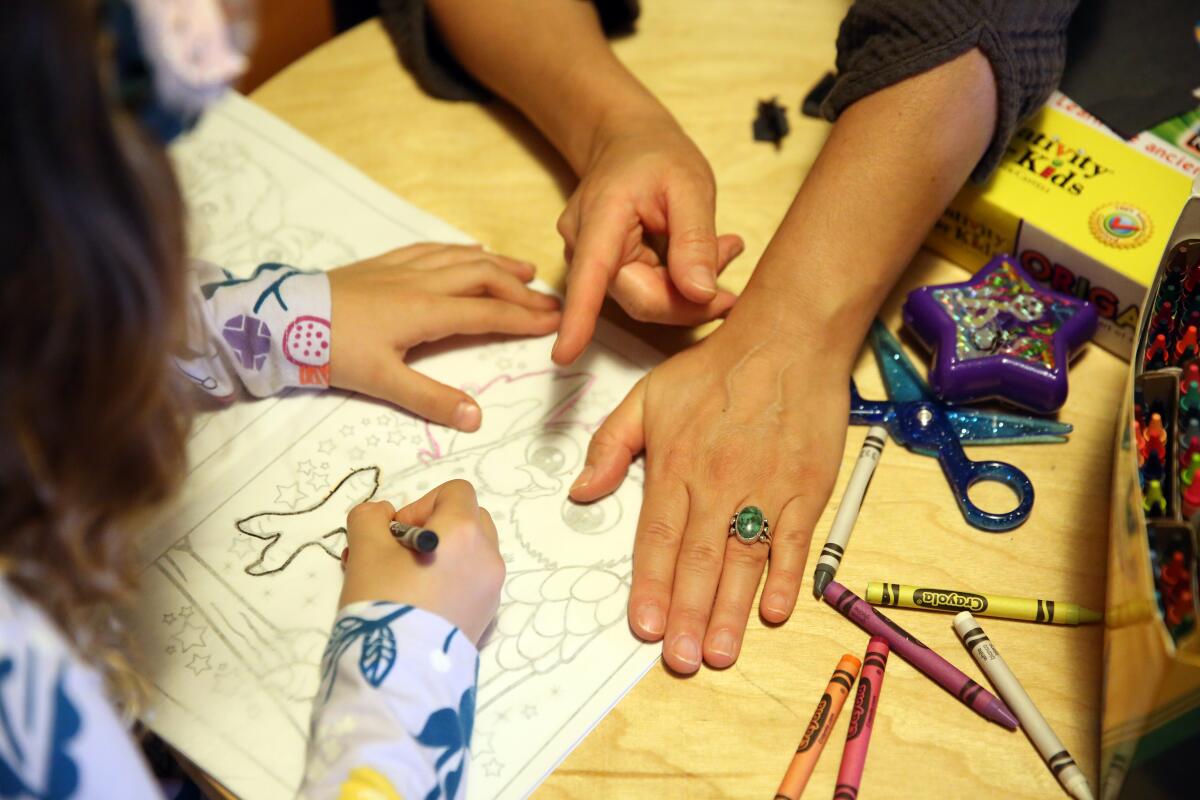

To make up for a dearth of play dates, I tried to become Cora’s “bestest” playmate: taking walks around our neighborhood, listening to educational podcasts together, looking for interesting leaves and rocks for a fairy house we planned to build. She even rendered a color pencil drawing of the virus in an attempt to understand it.

High school and college students are volunteering to address the educational gap between those who can afford private tutors and those who can’t.

In April, we constructed castles with Legos, inflated our blow-up pool and started a pandemic garden with cucumber, watermelon and cantaloupe seedlings. In May, we nurtured monarch caterpillars into butterflies and created paintings of spring roses. We even got her a caramel-colored bunny she named Glitter. Our garden never really produced much, but the watermelon leaves became Glitter’s favorite snack.

But all this was simply not enough to slake Cora’s yearning for the company of other children. And we never did build that fairy house.

In July, I was relieved when Carolina told me that a 3-year-old girl would be returning to day care. Cora knew the girl and they’d gotten along during pre-pandemic times. But the girl started to emulate my daughter — mimicking Cora. I thought it was sweet. Cora didn’t.

Despite Cora’s frustrations with distance preschool, we enrolled her in a virtual kindergarten at her Spanish immersion school in September. I was relieved that she’d start strengthening her Spanish — important to me because of my Latin American heritage. And we were fortunate to have Carolina help her.

This time, Cora was OK with seeing some of her friends on the screen. She scored straight “A’s” on all her subjects. I got excited. Would this be enough for her?

It wasn’t. Cora still longed to play with friends, up close and without masks. She wanted to touch them, hug them.

In October, I started my foray into pod recruitment. Sadly, I crossed out a couple of my friends who worked outside of the home or whose children continued to attend school with other kids.

Second, I started feeling out some of my friends with children around Cora’s age who I believed were as careful as we were. For me, that meant wearing face coverings outside — including parks and playgrounds — minimal trips to the grocery store and no indoor dining at restaurants.

I raised the issue with my husband — a self-described introvert.

“I don’t feel the need to expand the bubble, but I feel for Cora,” he said. “Now, the only way she sees people her age is on a video screen. I’m worried it might stunt her emotional growth.”

My husband said he’d consider forming a pod once I found a family.

Cora overheard our conversation and chimed in: “You know, in Spanish school the kids used to share food with me,” she said. “I really miss doing that.”

She then proceeded to advocate for a “social distance” play date with one of her schoolmates — a boy she’s smitten with whom she actively scrolls for in her Zoom class. She remembers playing with him in preschool.

“Can you call his parents, please?” she begged. But I didn’t know them.

“We’ll see,” I replied.

I decided to keep it to families we knew.

Experts say many students in kindergarten through third grade will struggle with online school. Here are some ideas to help make virtual learning work as well as you can.

First on my short list was my friend Ana, a speech therapist with two young daughters. They live nearby and all speak fluent Spanish. Perfect, I thought. But how to raise the prospect of a social pod?

I told her about how my older sister, the doctor, started a pod and how she’d encouraged me to do the same, for Cora’s sake.

“They get together and let the kids play without having to social distance or wear masks. It gives the kids some kind of normalcy and friend interaction,” I texted. “Would you be open to it? Feel free to say no if you are not ready for it. No pressure.”

I cringed in anticipation when the three dots appeared on my iPhone screen that indicated she was typing.

“I think that’s a great idea!” she wrote. Yes! But then more typing:

“However, grandma and their uncle visit Sundays and I see 2-3 speech clients, one of whom the mother started to teach again at a private school... I’m not a super candidate for a small bubble but wish I were.”

In a conversation, Ana told me she suspected Grandma — her mother-in-law — left the house to gamble.

So that was that.

Disappointed, I moved on to my friend Ingrid and her 6-year-old daughter, Olivia. Cora adores Olivia, and I knew from past conversations that Ingrid’s family was very careful and Olivia exclusively attends virtual school.

To my relief, Ingrid said she was open to the idea. But when she asked if I had child care, the situation got a bit tricky. I told Ingrid about Carolina.

“How careful is the nanny?” Ingrid texted me.

Careful, I replied, but her husband did work in a factory that makes medical supplies. I was told the workers wore masks. I was told they were distanced. I was told they were careful.

But I also told Ingrid I couldn’t guarantee that was the case.

Preparing myself for rejection, I tried to soften the blow — for both of us.

“No pressure,” I texted. “My feelings won’t be hurt if you decline.”

She told me she wanted to take “baby steps.”

She added: “Would be awesome if I could just be your nanny so we could keep the bubble really tight. The girls could do virtual school together. Just fantasizing. Or am I?”

But Ingrid didn’t speak Spanish, a complication for my daughter’s Spanish-immersion schooling. Also, I couldn’t leave Carolina without an income that I believe she’d come to rely on.

“I just wish we all lived in New Zealand,” I texted in exasperation.

We didn’t really talk about it again. Instead we met at a park — 2020 style. This meant wearing masks and barking at our children to stay away from each other and to keep their masks on.

My third and last attempt with another family also failed.

By this time it was November and infection rates had started to skyrocket. Deflated, I put the search on pause. Since then, COVID-19 seems to be closing in on us. I’ve had friends and family members fall ill to the virus, so for now we’re hunkered down. I feel defeated.

My only success was setting up a weekly virtual play therapy session for Cora in which she talks with a lovely woman about her day.

Also, Cora’s teacher helped me set up a Zoom play date between Cora and her crush. She was ecstatic and seemed satisfied with having him all to herself — even though it was on a screen.

And, she’s finally getting along better with the 3-year-old in her day care.

She knows her aunt and uncle — both doctors — received their first round of vaccinations a few weeks ago and that, with any luck, we’ll get ours this year. She’s starting to make plans for the future.

“After the coronavirus, we can go to the water park, right?” she asked us the other day.

“Yes,” I told her.

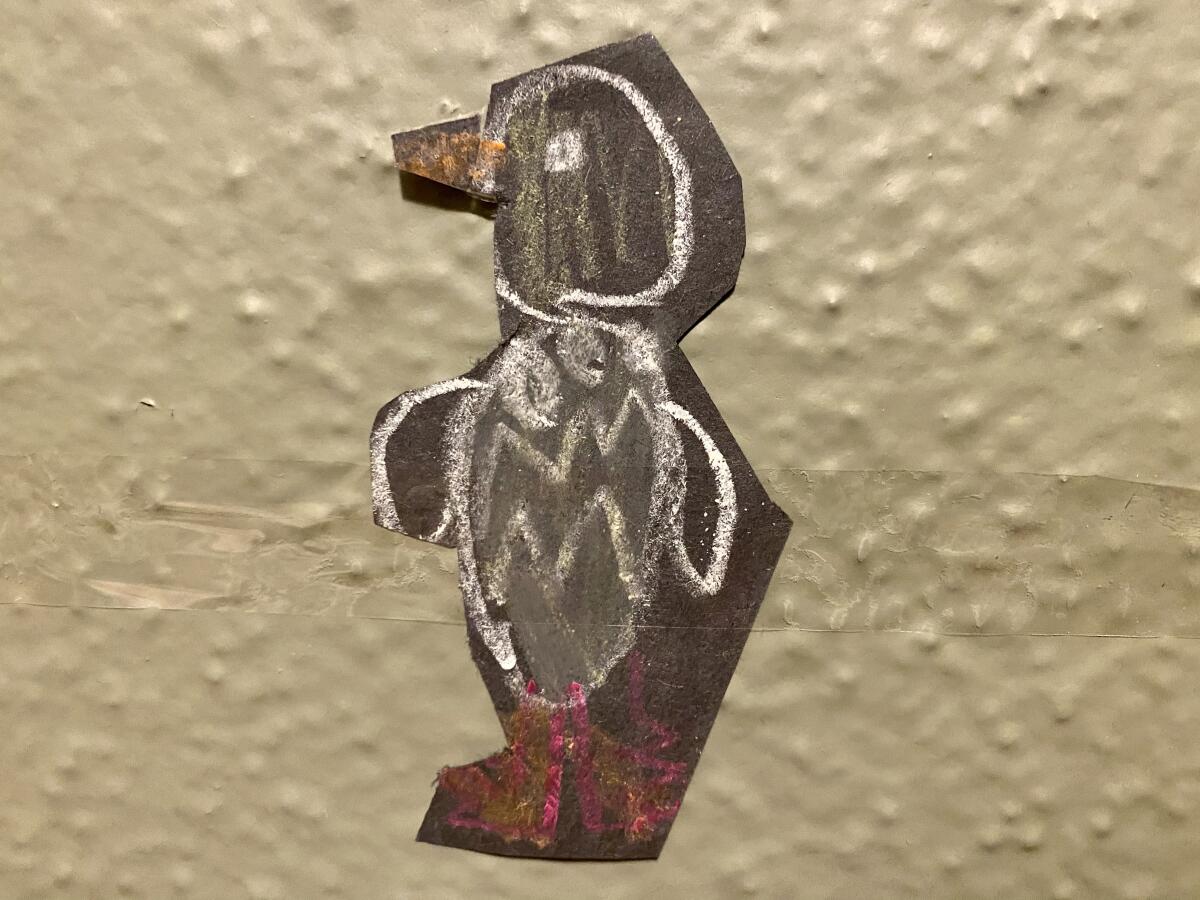

Over Christmas break she played in her room by herself for a couple of hours. After a lengthy silence, I worried and peeked inside. She was sitting at her kiddie table, drawing a penguin on black paper with the crayons our kind neighbor Ray gave her for Christmas.

She cut the penguin out and taped it to her bedroom wall. She sang to herself. She didn’t call out for me — not once.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.