MODESTO — A team of heavily armed SWAT officers, rifles aimed, converged on Frank Carson that morning in the driveway of his Turlock home. He was, the law had decided, a dangerous man, the kingpin of a murder conspiracy, and so they would take no chances with the shambling, heavyset 61-year-old criminal defense attorney, who sneered at them defiantly as they clapped handcuffs behind his back.

Carson knew what came next. They saddled you with the mug shot that would haunt you forever, looking grim and guilty and defeated. “All I wanted was not to look subservient and crawl like a dog,” he would say, “which is what they intended.”

And so as the camera clicked, Carson put on a carefree, open-mouthed smile, his eyebrows aloft in happy surprise above his thick glasses. Far from a first-degree murder defendant facing life in prison, he looked like a bumpkin who had won a new tractor. It was, a prosecutor would say, the same “good old folksy country boy” facade he had used to fool so many juries about his real nature.

His eight codefendants wore predictably stricken looks when their mug shots made the news that day in August 2015. Carson’s wife. Carson’s stepdaughter. Two brothers who ran a local liquor store. Their former handyman. Three members of the California Highway Patrol.

At the news conference, the Stanislaus County sheriff portrayed them as participants in a fantastic and complicated conspiracy that reminded commentators of “True Detective” or “Better Call Saul.” They were all accused of helping Carson to murder a scrap metal thief or to cover it up. By the official narrative, it featured a tenacious team of detectives bravely pursuing a cadre of corrupt cops who had danced on the puppet strings of a sinister figure named Uncle Frank.

But how did a defense attorney famous for his scorn of local cops actually enlist three of them in a murder plot? What kind of Svengali powers — what kind of Mephistophelean charisma — might this aging Modesto defense attorney possess? How did this case hang together, anyway?

Shifting story, macabre twists

So much of the case — the vast, costly, multiagency edifice that was State vs. Carson et al — perched precariously on the shifting word of one highly unreliable man. The government’s star witness was Robert Woody.

Woody was in his late 30s, a high school dropout with watchful blue eyes and a rough, mumbly patter. He was short and thickly built, a steroid-shooting gym rat. He had stolen cars and punched a cop and smoked meth, off and on, since his teens.

Carson had represented him pro bono on some stolen-property charges, and in exchange had asked him to keep an eye out for potential thieves around his much-pillaged Turlock property. Woody had been a fixture at the Pop N Cork liquor store down the block, working as an all-around handyman, mopping up, stocking the shelves.

He credited the men who ran the store — Baljit “Bobby” Athwal and his brother Daljit “Dee” Atwal — with rescuing him from the streets. They had given him a job. They paid to get his mouthful of bad teeth yanked and replaced. Then they had fired him, claiming he stole some soda.

Alone in his cell, Carson studied transcripts of Woody’s interactions with police. They reflected a story that shifted and changed and evolved, morphing under intense police pressure to fit a theory that implicated Carson. Carson’s anger mounted. He felt both contempt and pity for Woody, a man trapped by his own absurd story and overmatched by detectives who gave him no way out.

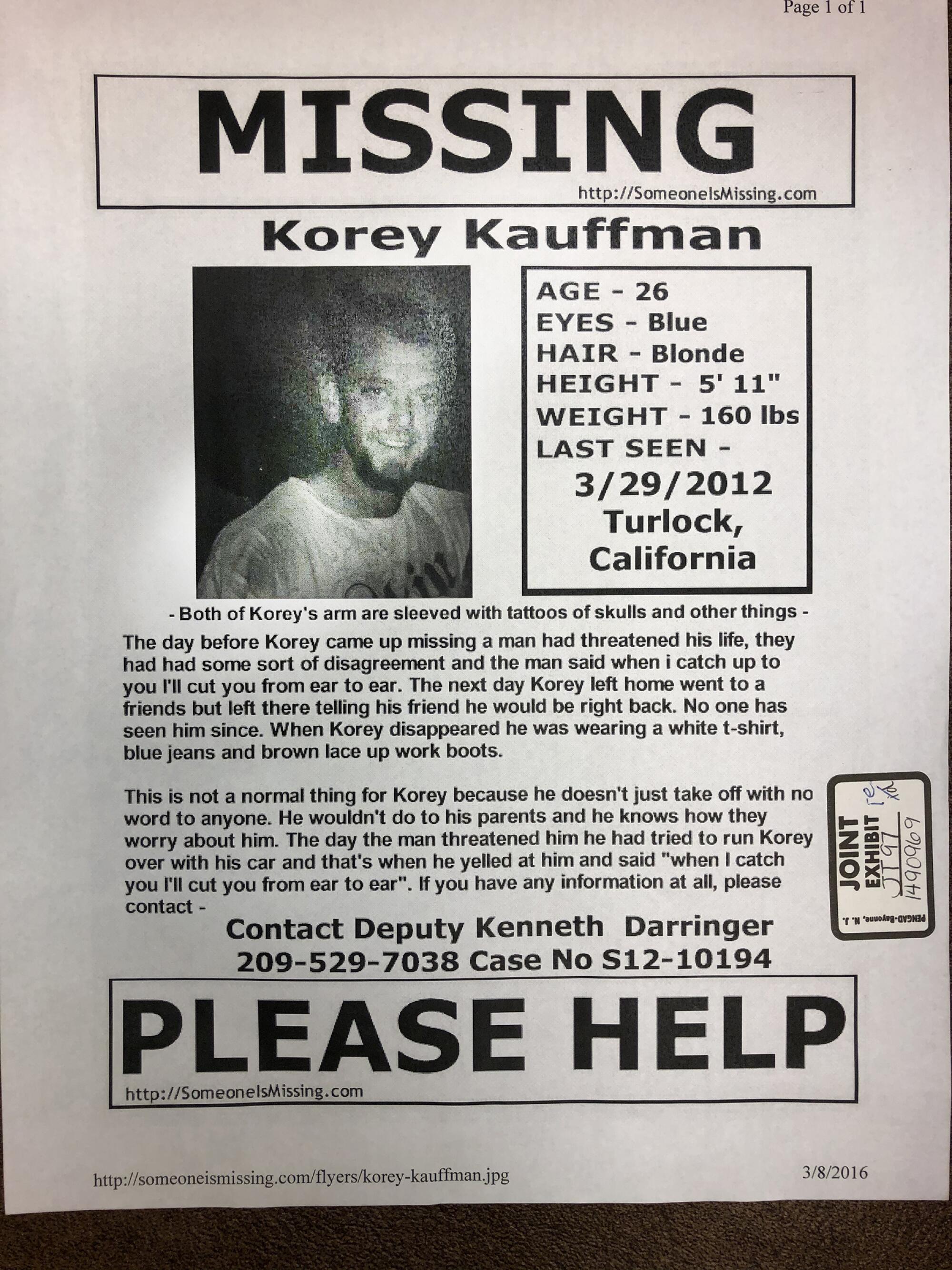

Woody had a braggart streak made gleefully macabre by his crystal-meth pipe. Amid the fumes one day in February 2014, in the back bedroom of the home he shared with his parents, he claimed — in a conversation secretly recorded by his girlfriend — to know what had happened to Korey Kauffman.

It was six months after a hunter had discovered Kauffman’s skeletal remains in the mountains, and rumors were crackling through the bars and backyards and drug dens of Turlock. Who had killed the young thief and dumped him out there? Why? Detectives themselves had fueled speculation with questions seeking to link the killing to Carson’s anger at local thieves.

Woody, a lifelong Turlock man, was well-placed to absorb the chatter. And now he told his girlfriend that he’d been responsible himself. He said Kauffman’s teeth had been yanked out, his body chopped up, so that pigs could devour his remains.

“The teeth,” he said. “They have to come out.” He added: “Never put it in one spot and never bury it.”

His girlfriend, Miranda Dykes, who had grown afraid of Woody and was secretly recording the conversation for police, pressed him for details.

“I was told he got shot,” she said. “Then I was told he got stabbed. People are confusing me.”

“Stabbed,” Woody mumbled through his meth haze. “Shot.” It was unclear whether Woody was attesting to one method or the other.

“I did all this alone,” Woody said.

Why? Kauffman had jumped a fence to raid the property of Woody’s former attorney to steal scrap iron.

“Carson,” Woody said. “Frank Carson.”

This was electrifying news to the detectives trying to prove their long-held theory that Woody and the Pop N Cork brothers had been acting as Carson’s watchmen and heavies, and had killed the thief in a burst of vigilante violence after catching him on the property.

Police moved quickly to find Woody, who had gotten word of the arrest warrant and disappeared. Dykes told police she did not believe the confession she had elicited. She thought Woody had bragged of the murder “to sound macho,” and posed a question that many people would subsequently ask: “How can they find his body if it was all cut up and fed to the pigs?”

Carson believed Woody had pilfered his gruesome story from the film “Snatch,” in which a mobster lavishly details a pig’s corpse-devouring prowess. Woody had gotten more wrong about the condition of Kauffman’s body than he had gotten right. There was no evidence that pigs had ever approached it; there were teeth in the skull; there were no saw or cleaver marks indicating it had been chopped.

“Robert, you confessed to a murder,” Modesto Police Det. Jon Evers told Woody after he turned himself in. “Do you understand that?”

“Confessed to a murder,” Woody mumbled. “What do you mean?”

District attorney investigator Kirk Bunch told him that his supposed co-conspirators — Carson, Bobby Athwal, his brother Dee — would pin the murder on him.

“They’re all gonna say you killed Korey Kauffman,” Bunch said. “Are you ready for that?”

Because Kauffman had been lured to his death on Carson’s property, Bunch said, Woody was facing a first-degree murder charge with the special circumstance of lying in wait.

More from Christopher Goffard

“We can go for the death penalty or life without possible parole,” Bunch said, “so it’s very important to you to tell exactly what happened, because that can mitigate that.”

Bunch said Woody knew things that only a participant in the crime could have known.

“I’m being very honest and candid,” Bunch said. “And Robert? I’m being very sincere, OK? Hey, we’ll get through this. I care.”

Bunch knew that Woody had been bragging about the murder to his family, too. They would be witnesses against him.

“Do you wanna put them in that position?” Bunch asked.

Over and over, in tones of mounting desperation, Woody repeated that he didn’t know anything about Kauffman’s murder.

“I made it up,” he insisted. “You know what I mean? I made it all up.”

Yes, Carson had asked him and one of the Pop N Cork brothers to keep an eye on his property. But that had been two months after Kauffman disappeared. Woody insisted his “confession” was just talk he’d picked up on the streets.

“Then why did you say it?” Bunch demanded.

“Stupid. I’m stupid.”

Woody looked increasingly trapped. He said he would kill himself, rather than go down for something he didn’t do.

“This is ridiculous. Whoever it is, is out there.”

Woody was taken to the bathroom in the company of an investigator, and later described the exchange to his defense investigator: “He told me to tell them what they wanted to hear,” Woody would say. “So that’s what I did. I told them what they wanted to hear.”

When they returned to the interrogation room, Woody demonstrated a marked new interest in helping. But he seemed not to know how, exactly. He said he had seen something on the night Kauffman disappeared.

“Where was it at?” Bunch asked.

“I’m not sure. I know it was somewhere.”

Bunch presented him with a scenario designed to put him at the supposed crime scene, Carson’s 9th Street lot in Turlock, but also to allow Woody to present himself in a minimally culpable light. Maybe Woody had seen one of the brothers attacking Kauffman there, and had tried to intervene?

Woody mumbled agreement with the scenario, insisting he had not lifted a finger to hurt Kauffman. By putting himself at the scene, Woody had played into the detectives’ expert hands and sunk himself even more hopelessly into a legal abyss.

Woody would try repeatedly to take back his confessions, but detectives weren’t having any of it. D.A. investigator Steve Jacobson told him that unless he cooperated he’d never see his kids again, and he wouldn’t be around to help his sick mother when she needed it.

Woody pleaded with Jacobson to tell him what he needed to say to go home. He was willing to make “false statements” if it helped, he said. “The story that sets me free,” he called it.

‘That there was a lie that I told you’

Woody was still trying to take back his confession 16 months later, when he sat in an interrogation room with detectives and his court-appointed attorney.

“That there was a lie that I told you,” Woody said of claiming to have been on Carson’s lot during Kauffman’s death.

Now Woody was pale, his hair shaggy, his muscular frame gone pudgy. His eyes shifted between the cops and his lawyer, as if looking for clues to what was required of him.

Again, Woody tried to tell them that his prior “confessions” were made up. But after intense questioning, Woody recanted his retraction and said, yes, he had been on the lot that night.

“And where is Korey at that point?” asked CHP Sgt. Kevin Domby.

“I imagine he’d be in the front with ’em,” Woody said.

Woody would use those two words — “I imagine” — again and again.

“Was Korey bleeding that night?” Domby asked.

“I imagine he probably was,” Woody said.

Woody did not offer a narrative so much as respond to detectives as they built a narrative, feature by feature. They suggested details; he assented to them.

Woody said that on the night Kauffman was killed, he and the Pop N Cork brothers loaded the body into Bobby Athwal’s Chevrolet Silverado to drive it to the mountains. No, he said, he drove up with just one of the brothers. No, he said, they actually buried the body in the lot beside the liquor store that night.

Domby suggested the depth of the grave.

“Two feet?” Domby asked.

“Yeah, about two feet,” Woody said.

Domby shared his theory. Woody and the Pop N Cork brothers had unearthed the corpse after a month and hauled it to the mountains in Bobby Athwal’s Chevrolet Silverado.

Why a month? Because a month after Kauffman’s disappearance, Athwal had reported his truck stolen, and it had turned up at a nearby orchard — burned in an attempt to cover up evidence that it had carried Kauffman’s corpse, Domby believed.

Woody assented to this account. His story resembled a novel in progress, cycling through drafts to satisfy an editor’s stringent requirements.

What route did they take into the mountains? Woody didn’t know. Jacobson called up a Google map on his laptop and said, “This is where the body was found up in here.”

When Woody was out of earshot, his court-appointed attorney, Martin Baker, told Domby, “I want to close this case. I don’t want to be stuck in a six-month-long murder trial with this guy.”

A trip to the body-dump site

Detectives had tried to confirm Woody’s story. Had he really helped to bury a corpse in the dirt next to the heavily traveled Pop N Cork, in an illuminated lot overlooked by a two-story apartment building? Forensic experts searched the dirt and found no trace that Kauffman’s body had ever been there — no blood or other bodily fluids, no telltale signs of insects that would have fed on it, not a scrap of the tarp he said he’d buried the body in.

There was another possible way to confirm Woody’s account. In August 2015, a four-car caravan of law officers accompanied Woody to the mountains of Stanislaus National Forest in Mariposa County. They drove him to the general area where Kauffman’s remains had been found, parked, and escorted him down the road.

Could Woody lead them to the body-dump site? If so, it would be shatteringly persuasive evidence of his credibility. Prosecutor Marlisa Ferreira, who was there, would say that Woody directed her and the team of cops to a spot above the ravine where the bones had been found.

It was 2015, and smartphones were already ubiquitous, but none of the many law officers recorded this important walk. It didn’t seem “probative,” Ferreira said, and the battery was low on the official camera.

Sheriff’s Det. Cory Brown held that camera, but he did not begin recording until he stood in the ravine, already just feet from the body-dump site. His camera showed Woody standing on the road above, shackled, supposedly indicating where he’d dumped the body.

“I guess right about there,” Woody said.

This was just a few feet from where Kauffman’s skull was discovered, Ferreira would say, adding triumphantly: “We all had like goose bumps.” She said it showed that Woody was telling the truth.

There were good reasons to doubt this. Det. Brown’s video doesn’t show them, but his report noted that evidence marker flags were still visible in the ground. They had been planted at the scene two years earlier, to indicate where the scattered bones had been found. Couldn’t Woody have used the flags to guess?

Ferreira insisted the flags had not been visible from the road, where Woody was standing. But no one had videotaped the scene from Woody’s point of view to prove this, and defense attorneys would say the flags were visible from the road — it is how they found the site themselves.

‘The Trials of Frank Carson’ is a true crime podcast about power, politics and law in California’s Central Valley.

Woody was not done. Eager to maximize his value as a witness, he made his story even more irresistibly dramatic: He’d seen Carson himself at the murder scene. He told Ferreira that Dee Atwal had shot Kauffman and then handed Carson the gun.

“And what does Carson do once he has the gun?” Ferreira asked.

“Leaves.”

Now the star witness was putting the murder weapon in Carson’s own hand. Except one of Woody’s own lawyers didn’t believe it. “No one’s going to believe this stupid story,” Bruce Perry said he told Woody.

In a letter to the D.A., Woody admitted he had invented the new details “in a misguided attempt to help the D.A.” But he would stick by the rest of his account. It’s hard to imagine how Woody might have rendered himself less credible. In another county, prosecutors might have balked at putting him on the stand as the spine of their case against a prominent local defense attorney.

Carson felt a mixture of contempt and pity for Woody. “He’s a low-level criminal,” Carson would say. “I can’t get all that mad at him, OK? He’s a victim. He’s stupid. He’s doing time for something he didn’t do.”

The Pop N Cork connection

Woody could not lead detectives to a single piece of physical evidence proving his involvement in the crime, but the authorities’ zealous embrace of his wildly mutating account explained much about the charges that was otherwise baffling.

How did Carson’s wife, Georgia DeFilippo, and his stepdaughter, Christina DeFilippo, stand charged with conspiring in the supposed murder plot? Christina, an art student, had lived in the house on the Turlock lot where Kauffman’s murder had supposedly happened.

Studying mom-and-daughter text messages, detectives found that they had been aware of Carson’s concern about thieves on the lot, that Christina was supposed to alert her stepfather if the motion detector went off, that he sometimes patrolled his lot with a gun.

When a detective asked Christina whether she remembered any commotion outside on the night prosecutors say Kauffman vanished, she replied that she hadn’t, and called her mom to say, “They’re like really being aggressive,” adding: “I don’t know what to do about it.”

“Don’t do anything about it,” her mother said. “Just do what you’ve been doing.” Their knowledge of the alleged crime was now assumed; this was confirmation of a cover-up, to the law.

How had three CHP officers been dragged into this case? The nexus to Carson was the Pop N Cork, co-owned by his former client, Bobby Athwal. The officers loved to hang out there — the back room was a safer place to drink than the local dive bars — and so they fell under suspicion.

When Dee Atwal complained that someone was following him, maybe to rob him, CHP Officer Eduardo Quintanar Jr. laughed and suggested he buy a mirror to check under his car for trackers. To the custodians of the law in Stanislaus County, this suggested he was “explaining how to thwart investigative techniques” to a man under suspicion for murder. Conspiracy.

CHP Officer Scott McFarlane told investigators he had seen the scrap metal thief pedaling around the neighborhood two days after he supposedly vanished, which authorities believed was intended “to muddy the timeline of Kauffman’s murder.” Conspiracy.

A cellphone expert examined the phone records of a third CHP officer, Walter Wells, and claimed his cellphone had pinged off the same cell tower sector as Kauffman’s 21 times in the weeks after the thief’s disappearance.

The D.A. rejected the innocent explanation — that Wells lived and socialized in Turlock, which had few cell towers, and that countless other local cellphones would show similar results. Instead, the D.A. decided Wells had been carrying Kauffman’s phone to confuse investigators. Murder.

Carson, examining the prosecution theory, regarded it as ludicrously weak. But the government had great leverage. His codefendants were facing prison terms and career ruin. Maybe some of them would tell prosecutors what they wanted to hear. A career defense attorney understood the frailty of human nature, if anyone did.

Confronted with enough pain, people could be expected to save themselves, to climb aboard what investigator Kirk Bunch had called “the witness bus.” More than once, Bunch had told people that would happen. He had sounded supremely confident.

More from this series:

Modesto defense attorney Frank Carson spent years accusing local police and prosecutors of corruption. One day they accused him of masterminding a sprawling murder and cover-up conspiracy.

Frank Carson barely survived his 17-month murder trial. But his days were numbered.

Listen to the Podcast:

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.