Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

After a night of ragged sleep, a woman who solved murders woke before dawn in her red-tile suburban home and padded across the hardwood floor to her closet. She thought hard about the right color to put on. What do you wear to interview a serial killer?

It was the first of a thousand calculations Anaheim Police Det. Julissa Trapp would have to make that day. For some, she would follow the advice of the Homicide Investigation Manual, or of the small army of local detectives and state investigators and FBI agents who would watch her work.

Many other decisions would be unconscious or instinctive or hard to fully explain.

Trapp was 37, a veteran detective. She had entered this case a month earlier, when she stood beside the body of a young woman at a trash-sorting plant. Since then, she had walked between her city’s cheap stucco motels, studied trash routes and sent teams chasing suspects from Oklahoma to Oakland.

The Times’ Christopher Goffard, creator of “Dirty John,” examines a series of Orange County killings and a detective’s quest to solve them.

There had been dozens of dead ends … and then one improbable fingerprint that led them to the door of an innocent man, who led them to an alley, which made them gamble on an idea that had initially seemed crazy … and suddenly she was at the center of a case involving 75 cops from seven agencies.

And now, on Day 29 of the case, it would come down to this: A detective. A killer. A windowless 8-by-10 room. A psychological duel that demanded as much instinct as training, and might require her to surrender more of herself than most cops were prepared to give.

At stake was more than a confession. This might be Trapp’s last chance to learn the fates of three missing women, and, if they were dead, to find out where their bodies were and bring them home.

The detective had missing persons of her own, and she carried them everywhere, inked on her skin, confronting her every time she got dressed. They were represented by four small black birds, tattooed in a straight line under her collarbone. They were swallows — the bird that carries souls. Each bird was an unhealable wound from which she did not wish to escape, but also an image of hope.

Today Trapp was searching for the right persona to confront a man who killed women and threw them away like litter. When she was assigned to sex crimes, she had worn pink. It was a useful disguise, because it made her seem exactly what she was not: pliant and harmless.

For this adversary, she thought it was important to look approachable but also to project strength. She did not want to appear soft. Pink wouldn’t do. She found an emerald green blouse. Green seemed like a strong color. She put it on, over the swallows, and grabbed her badge.

::

When Julissa Trapp drives through her hometown of Anaheim, it feels to her like “one big crime scene.” Every street leads to the site of a remembered stabbing or shooting or chase, to close calls and hard lessons, to dead-eyed killers and inconsolable mothers.

It’s a mental map of what the jaded call “Anacrime,” the crowded city of 350,000 that encircles Disneyland. It’s a map of long business strips that sprang up more than half a century ago and were sidelined by history, the wide boulevards dotted with disappearing relics of indigenous California weirdness — space-age car washes, gaudy neon signage, kitschy theme motels.

It’s a map of neighborhoods that tourists avoid, of blocks menaced by gangs and shadow economies fueled by drugs and sex, of pay-in-cash motels with cages on the night windows where resident families splash in tiny pools hard by the parking lot.

Of course, all of this shares a geography with Trapp’s most personal memories, and some of her happiest. Down that street is the little yellow house where she grew up, and down that one is where she first pulled her gun. Over there is her elementary school, and here is where she patrolled in her 20s — a pixie-haired cop so small at 5 feet 3 that she had to sit on a phone book to see over the steering wheel of the Chevrolet Caprice they assigned her.

Down that way is La Palma Park, where as a rookie she came upon a guy out past curfew. He asked her age and said, “Isn’t it past your curfew?” Over there is where she chased a gunman through a series of backyards and gave the wrong block when she radioed for backup, causing a sergeant to bark: Was she trying to get herself killed? She drove up and down the streets and memorized them to ensure it never happened again.

She applied to homicide, and was turned down, four times. After one rejection she asked a senior officer, “What do I need to do to get there?”

He told her to get experience in gangs, family crimes or sex crimes. She worked all three. In sex crimes, she won detective of the year. In gangs, her partner rode alongside her in silence for weeks, the implicit message being: Prove you belong here.

She got to homicide in 2010, on her fifth try, and won detective of the year again. She did not feel instantly accepted. She looked like the antithesis of a grizzled murder cop, with a kind face, soft features and freckles on her cheeks, but she had a reputation as brash.

“If you haven’t secured my crime scene, I’m going to let you know that I’m not happy about it,” she would say. “If you spit seeds in my crime scene, you’re going to hear about it.”

Once, at the scene of an 8-year-old’s shooting death, she snapped at a male sergeant who didn’t seem to have a single useful thing to tell her: “What do you know?”

A male lieutenant pulled her aside to say her manner of speaking wasn’t appreciated. She hadn’t violated any policy. They were just talking about that elusive and subjective thing, “tone.” It wasn’t the last time.

“Ultimately telling me to ‘chick up’ a little bit,” she would say. “I’m like, ‘That’s not my style.’ I’ve got to throw in a ‘please’ ‘cause I’m a girl?” One of her favorite TV shows was “The Closer,” about a female detective who often bruised colleagues’ egos en route to winning spectacular confessions.

‘If you spit seeds in my crime scene, you’re going to hear about it.’

— Det. Julissa Trapp

“The tone thing” became kind of a joke among her partners, like J.D. Duran, who is the longest-serving homicide detective at the Anaheim PD. Of the 43 partners he’s had in his 22 years there, she’s one of just three women. He and Trapp have a pact that if unnatural death befalls one of them, the other will take the case, which is pretty close to the highest compliment a murder cop can pay another.

She developed some nicknames, like Hurricane Julie, which referred to the force she became in the thick of a case, and The Cape, because she flapped around like one, trying to hang on to the neck of a suspect twice her size who objected to his arrest.

Duran said Trapp has still another nickname: British Julie, a character who smiles through her teeth while carefully enunciating syllables of biting disapproval in the direction of, say, the beat cop spitting sunflower seeds at her crime scene.

::

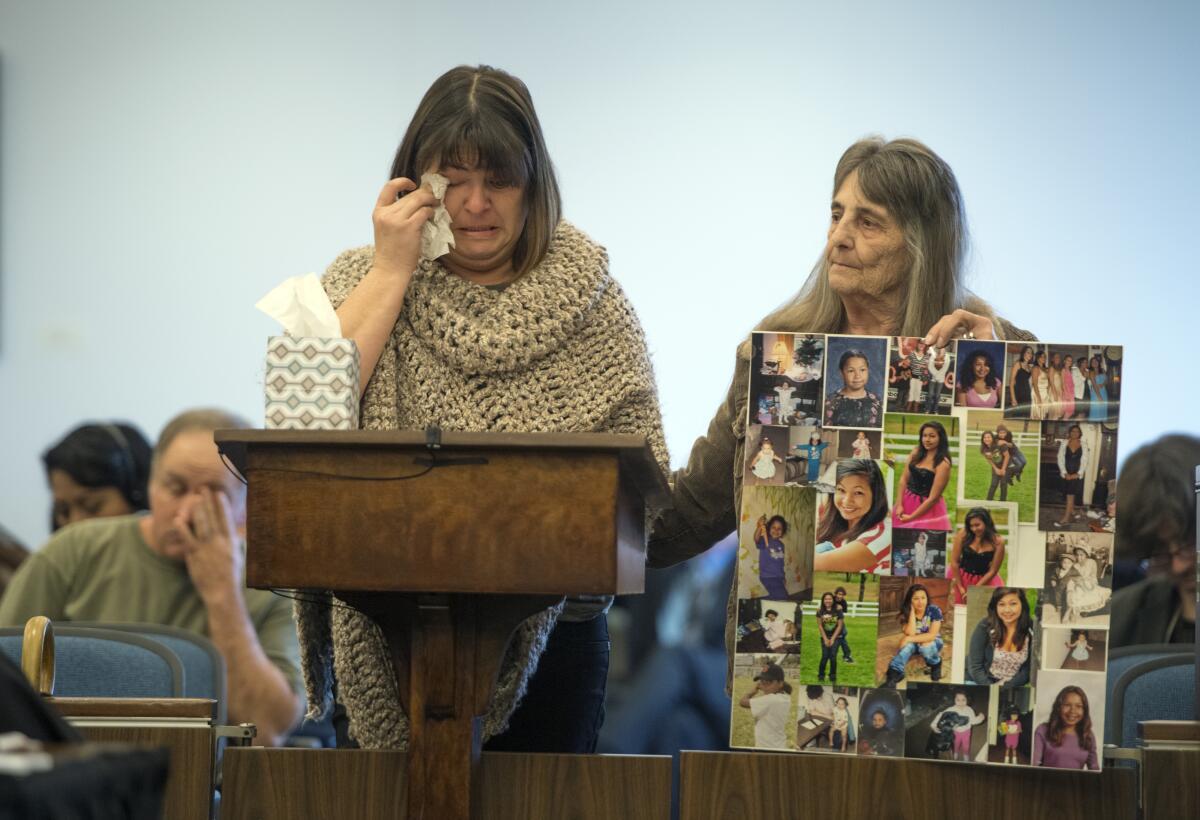

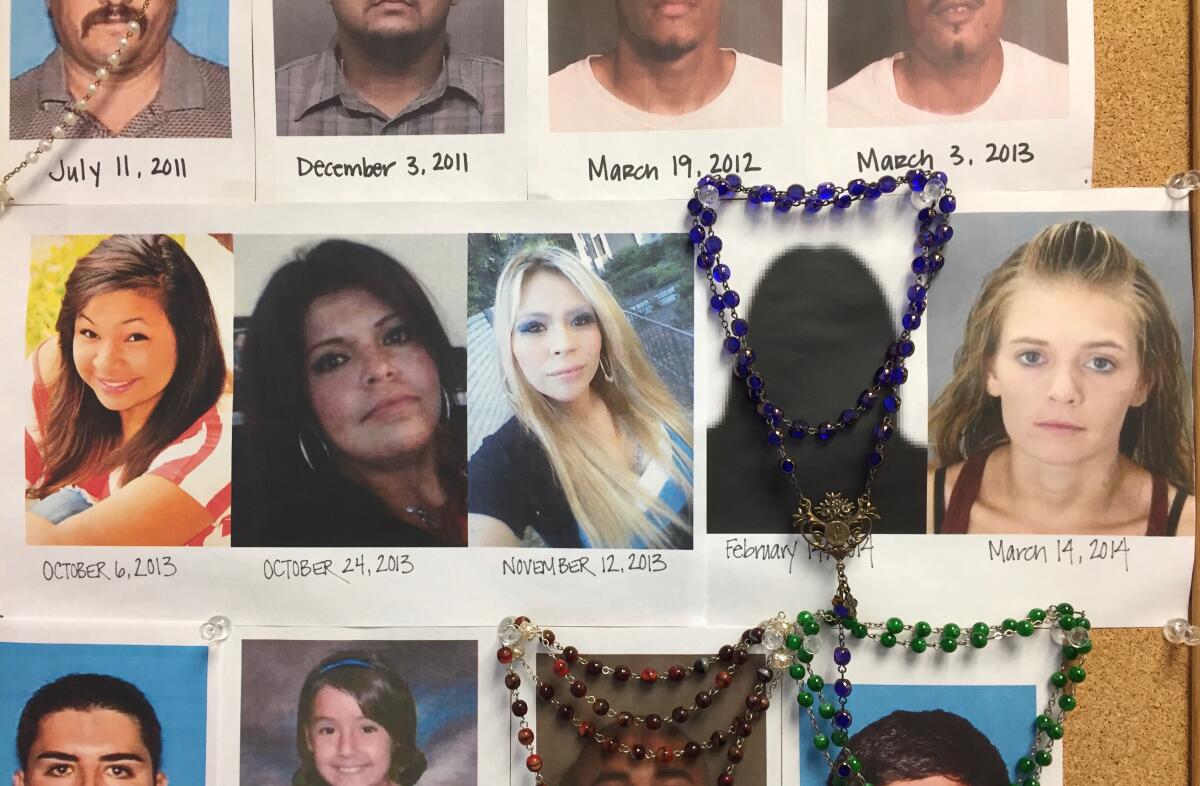

The women who began disappearing from the streets of Santa Ana in fall 2013 did not come to Trapp’s attention for months. She would come to know their life stories intimately, and for years their faces would stare at her from the corkboard beside her cubicle. She kept them there, to remind herself that her work wasn’t done.

They were mothers and daughters, friends and sisters, aunts and wives. By law enforcement logic, they were also in a line of work — street-level prostitution — that put them in a certain category: a population prone to drift and disappear and reappear somewhere else.

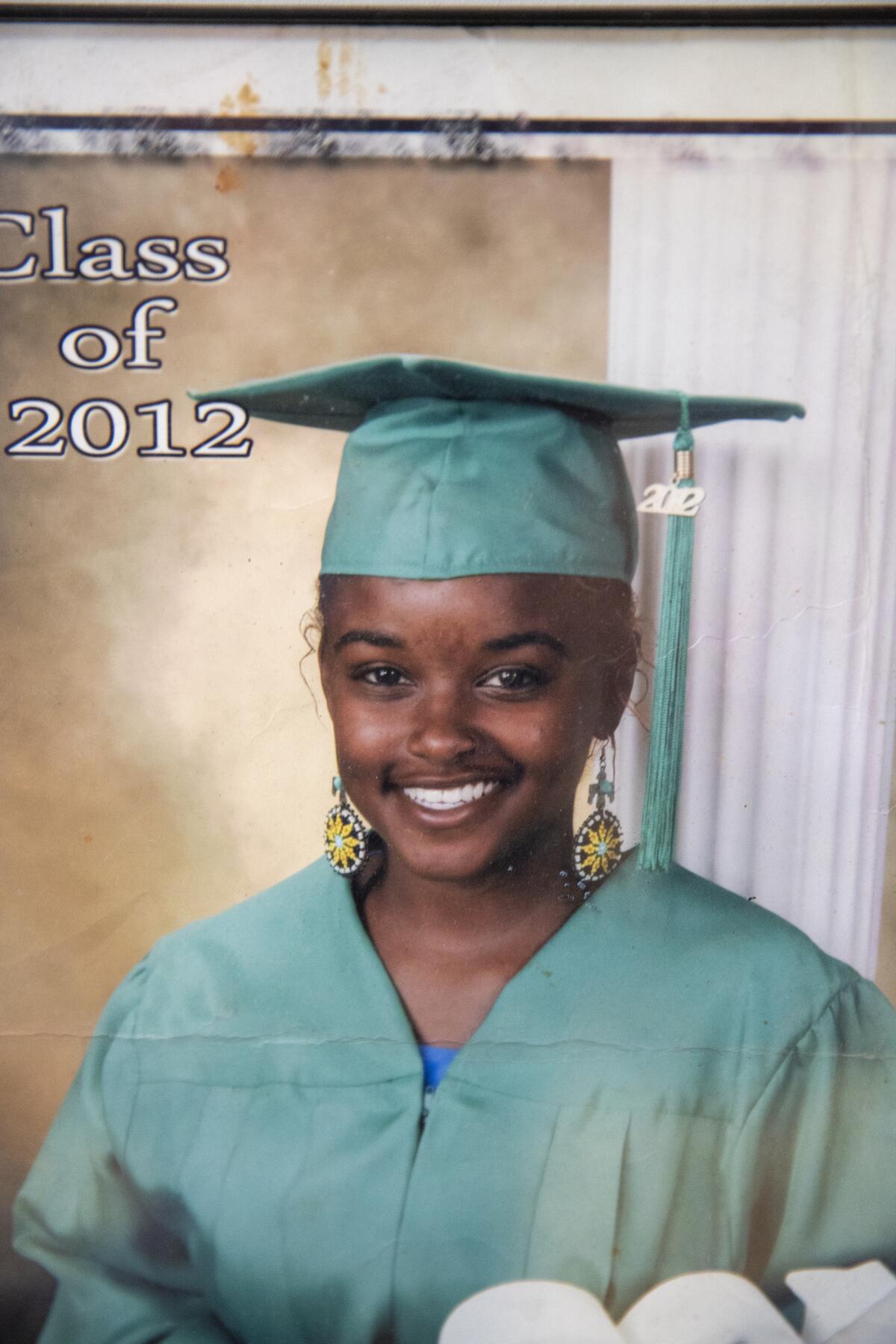

Kianna Jackson disappeared on Oct. 6. She had just turned 20. She had grown up in Northern California’s logging country, left home in her late teens and had been living in Las Vegas with a man her family came to believe was a pimp. She had just taken a Greyhound bus to Santa Ana.

Her mother, Kathy Menzies, reported her missing to the Santa Ana Police Department when she didn’t hear from her for a few days. The man who answered the phone looked up Jackson’s record and found she’d previously been arrested for prostitution. “Prostitutes work circuits,” he said, which meant they cycled from city to city.

Menzies tried to make him understand — her daughter wouldn’t just disappear. She called or texted regularly. Menzies contacted the Orange County morgue and every hospital she could get the number of. She called the Motel 6 where her daughter had been staying. Jackson had left her things in her room and never returned.

Weeks passed, and her mother’s panic and desperation grew. At the Santa Ana PD, it was not considered a high-priority case. The department got nearly 100 missing persons reports a month, many of them runaways who quickly turned up. At the time, the department had just one full-time missing persons investigator, a civilian.

It would be months before police got a warrant for Jackson’s cellphone records to determine where it had last pinged.

In the meantime — 18 days after she went missing — a second woman disappeared.

This was Josephine Monique Vargas, 34, who stayed with family when she wasn’t at a Red Roof Inn with her husband. Her nickname was “Giggles” because her laugh was irrepressible, even in church. She had a crack cocaine habit, and had lost her children to child protective services. She worked the area around 1st Street.

The family was having a backyard barbecue one afternoon when Vargas announced she would walk up to the 98-cent store to buy some napkins. She never returned.

Her sister, mother and husband went to the Santa Ana police to file a report. Months passed before detectives got her cellphone-location records.

Nineteen days after Vargas’ disappearance, 37 days after Jackson’s, Martha Anaya disappeared. She was 27, a local woman with two daughters. One of them, Melody, who was 12 at the time, would recall that money was always tight, but they had inexpensive season passes to Knott’s Berry Farm, where they went twice a month to ride roller coasters and eat carne asada fries.

Melody was anxious about whether they could pay the rent and buy her schoolbooks, but her mother tried to reassure her: She’d find a way. When Melody asked her what she did for money, her mom said “the government” and pointed to her bad knee.

“Whenever she needed help spelling something she would always tell me, she’s like, ‘Why do I need Google if I have you? You like know everything,’” Melody would recall. “So she would always make me feel good about myself. She would always make me feel smart and she knows I’m going to be something. She always told me, ‘When I’m old you better take care of me.’”

One day, her mother didn’t come home. She wasn’t texting. She wasn’t calling. Melody thought maybe she hadn’t paid her phone bill. But more time passed with no word, and she knew something was wrong.

When they went to the police, the family says, they got the same answer the other families got: The missing woman had a record for prostitution, and it wasn’t unusual for prostitutes to drop off the grid for a while.

Herlinda Salcedo, Martha Anaya’s mother, asked for a meeting with the Santa Ana police chief and pleaded for his help. She says she was told that her daughter was probably enjoying herself in Las Vegas.

That chief has since left the Santa Ana PD. “Unfortunately, the factors associated with these victims’ lifestyles made it difficult to determine whether these females were missing on their own accord or the victims of foul play,” the department said in a recent statement.

Over in Anaheim, Det. Julissa Trapp was busy with her own caseload. Her city got about a murder a month. She was not aware of the missing women in Santa Ana until late in 2013, when she turned on the news. The mothers were posting fliers and going street to street asking if anybody had seen them, begging police to take it seriously.

Trapp would remember thinking it was odd. But it would be months before her story and theirs collided.

::

The downtown headquarters of the Anaheim Police Department is a red-brick building that cops call the Barn, and it has been a second home for Trapp for most of her life. She’s been showing up there since she was 15-year-old Julie Rios, Police Explorer Badge #8, an Anaheim girl trying to learn her radio signs and begging for ride-alongs. She was a cadet at age 20, working the walk-in counter, and a sworn officer at 21.

At the moment she’s the only woman in her department’s eight-person homicide unit. Off duty, she drinks the most expensive whiskey she can afford, and likes to throw axes. Occasionally, she swims with sharks off the coast of La Jolla. She’s a devout Catholic who prays at every meal and goes to Mass faithfully.

One of her favorite expressions is “There’s no crying in homicide,” which is more often abbreviated as, “No crying in homi.”

She says it a lot, maybe because more than some of her colleagues, she needs to. With every murder, a cop must strike some balance between caring and coldness, between empathy for the victim and the clinical detachment required to solve the case.

In Trapp, it’s a vivid contest. Her supervisor, Sgt. Jeff Mundy, says she’s different from a lot of detectives in that she works cases from a personal connection, the kind others avoid because it would eat them up. She refers to victims by first name and calls their families on birthdays and anniversaries. For everyone whose face goes on her corkboard, she buys a rosary.

::

Trapp’s parents are from Zacatecas, Mexico. Her mother cleaned other people’s houses and kept their own immaculate. Her father had little education when he came to the United States in his teens. He was a gardener, dishwasher, shoe polisher, night porter, busboy and finally — by the time he retired — a banquet manager supervising 175 people at the Anaheim Hilton.

In the early 2000s, when she was still Julissa Rios, the Anaheim Police Department gave her a new partner, a burly SWAT cop of German ancestry. They rode in icy silence.

He had heard she was abrasive and tough to work with, and now he thought: Good Lord, she’s cocky. She thought: Damn, he’s full of himself. One day when she was sore from a recent surgery, he offered to carry her equipment bag to the car. Then they were friends, and then she was in love with Eric Trapp and had his surname.

She was an Anaheim girl with parents from Mexico, and he was a surfer from Newport Beach, so it was fun to bring him to her uncle’s farm in the Inland Empire and introduce him to pajarete, a drink that combined cocoa powder, tequila and a jet of milk right from the goat’s udder.

They were both foodies, and made lavish five-course meals for friends, the kind of couple who don’t just cook dinner but Create a Menu. They were a whirling duet with Le Creuset cookware and a kitchen patter right out of the squad car: Who’s the primary on the rack of lamb and who’s the backup? “Jules, hand me that pan.” “Stand by.”

She was in her early 30s and still working gangs when they decided to start trying to have children. Her dad had been one of nine, and her mom, one of 20, would tell her, “Mija, you shouldn’t wait.”

When it didn’t work, and still didn’t work, she began to feel as if police work was specifically designed to punish her: All day long she found herself in the company of gangbangers and dope fiends who had no idea how to care for their kids and didn’t seem to want them, kids they left with broken arms and cigarette burns.

“Anyone I ran into who had a child and didn’t see the child as this amazing gift,” she would say, “it pissed me off.”

Trapp found it hard to figure out God’s plan for her. Every tweaker can get pregnant, but not me? They’re able to do this basic thing, and I can’t? When she talked about her trouble conceiving, friends became accustomed to a tone of bitter irony: Maybe if I was on meth …

Her mother thought maybe it was the stress of chasing gangsters all day, and insisted she see a sobadora, or fertility masseuse. It didn’t help.

Trapp researched her church’s stance on in vitro fertilization. The Catechism of the Catholic Church called artificial insemination “morally unacceptable,” but the department chaplain reassured her that she’d be doing God’s will by building a family.

She endured a physically taxing, emotionally draining gantlet of needles and doctor’s visits. Needles in her stomach, to make the follicles grow. Needles of progesterone in her backside, self-administered twice a day, till she was covered with bruises.

The doctors retrieved her eggs, fertilized them and implanted them. She got pictures of the growing embryo. The pregnancy failed. They tried another doctor, and this time she carried to eight weeks. She went into her bedroom closet with a bottle of tequila and raged at God.

The maddening, hard-to-fathom disconnect between effort and result was not the least of the insults to her view of the universe and her place in it. Didn’t her whole career prove the link between obsessive focus on a problem and the conquering of it?

“In life, when you hit a roadblock, you go around it,” she would say. “There’s always a way.”

Trapp remembered the nights she came home from the police academy with her arms bleeding from the cinder-block wall she was expected to climb, and how she eventually willed herself over it.

She liked to be in control, but the world of IVF stripped away every illusion of it.

It was hard to be around friends with kids. She went to a baby shower and headed straight for the bar. She did not like this embittered version of herself. She didn’t like how people felt the need to tiptoe around the subject.

She was in homicide about a year when they tried again. The needles, the implantation, the pictures. She stayed home on bed rest, crocheting a baby blanket.

Looking through baby-name books, they decided that if it was a girl, she’d get to pick the name. A boy, and Eric would pick, provided her mother could pronounce it. She heard a heartbeat, but carried for just 10 weeks.

‘In life, when you hit a roadblock, you go around it. There’s always a way.’

— Det. Julissa Trapp

She went into the closet again. It felt as though a basic compact with her creator had been broken.

By then the Trapps had spent $100,000, pretty much their entire savings. Eric was willing to borrow if she wanted to try again. But she was tired of feeling like a failure, and of being angry all the time. They talked about being foster parents, with an eye toward adopting, but she had friends who had to give up their foster kids and she was sure that would hurt too much.

She had always been dedicated to her job, her grim and unique task in the universe, but it acquired a new meaning now. She wanted to be a mother, but now she thought, Maybe that is not who I am going to be. Maybe I am the woman who finds answers for other mothers.

::

On the Friday morning in March 2014 that Trapp’s life became permanently entwined with the missing women in Santa Ana, she was in Anaheim doing something she relished: standing before a roomful of students.

She was telling excited seventh-graders about the details of fingerprint collection, explaining how the forensics team used Super Glue to seal prints. She hoped to inspire some of the kids to consider police work.

Her buzzing cellphone interrupted her talk about 11:15 a.m. A text from the homicide-squad secretary. She looked at it and cut her talk short. She thanked the students, politely excused herself and walked swiftly to her car.

The text told her to get to Republic Waste Services on North Blue Gum Street. It said: “Possible human remains.”

When Det. Julissa Trapp arrived, her partner was already knee-deep in the trash surrounding the young woman’s body in the cavernous, ear-splitting warehouse.

For Trapp, it was hard to imagine a more chaotic crime scene than Republic Waste Services in north-central Anaheim, where tons of trash surged across a series of elevated conveyor belts, fed by an endless procession of garbage trucks.

A rat scurried over Trapp’s shoe. Pigeons wheeled and flapped. The stench was thick.

Machines echoed off the walls and high ceiling. The belts kept rolling, except for the one on which Det. Bruce Linn was currently standing, the one where a worker had spotted what looked like a protruding human foot.

It was Friday morning, March 14, 2014. The victim was a blondish young woman, unclothed, her jaw broken, her leg snapped, her skull crushed, her body wrapped in a shredded blue tarp amid what looked like debris from a residential remodeling job.

Who was she? How did she get here?

The detectives decided to collect trash in a wide radius around the body — 20 to 30 feet in each direction. They were looking for addresses that might lead them to the trash bin she had been left in.

Linn spotted something else — a tube of acrylic sealant labeled TremGlaze. It was the closest to a hard surface he could find, the kind that might hold a clean fingerprint. With a gloved hand he dropped it carefully into an evidence bag.

Trapp and Linn had seen many varieties of savagery, but the singular coldness of the scene struck them both. “Everybody dies — I get it. The death rate is one per person,” Linn said later. “But to get thrown out in the trash? Now, that ain’t what you do.”

Linn was a transfer from the fugitive-surveillance squad who had spent years in disguises, often unwashed Dickies and a tool belt — “a dirty mechanic, a dirty plumber, a dirty elevator-repair man” — and so had not hesitated to climb into the trash. He had deep-set, watchful eyes set in a hard-boned face that looked as if it could absorb a heavyweight’s right cross.

He had worked murders with Trapp for more than two years, wearing a suit and tie and short-brim fedora. The camaraderie was instant, and by now they could sometimes read each other’s thoughts with a glance. At the office, their cubicles were a few feet away, and they liked to get each other’s attention by launching spongy ping-pong balls at the other’s head.

“Yin and yang,” he called their partnership. Both were devout Christians, Trapp a Catholic who liked Blanton’s whiskey, Linn a Calvary Chapel evangelical who believed in the Bible’s inerrant word and shunned alcohol.

He could debate theology tirelessly, and liked to ask why she sometimes prayed to Mother Mary, rather than directly to God. “Every once in a while, I want to talk to a woman,” she would say, and sometimes had to add: “Can we just get back to murder?”

“She’s all girl,” he would say when he teased her about the price of the Christian Louboutins and Manolo Blahniks she wore off duty. “She’s a dude,” he’d say when he recalled how hard she punched the bag in Krav Maga class or took control of a scene.

Linn’s approach to his job was informed by his years hunting fugitives, where he had been a step removed from the victims’ families. The suspect was his focus.

Unlike Trapp, he didn’t pin the victims’ faces on his cubicle wall. Neither did any of their veteran partners, one of whom was once asked how he could function clear-headedly after seeing decades of murder victims, and who replied, “I don’t know them.”

Trapp was different. She went out of her way to know the victims, and their families’ bottomless pain, which she somehow seemed able to absorb without limit. “That’s what makes me push,” she said.

::

When Anaheim police stop suspects, their tattoos are noted and fed into a database, and by this method detectives quickly identified the victim as Jarrae Estepp, 21, of Ardmore, Okla. An officer had detained her the year before, on suspicion of prostitution, and recorded that “Jodi” was inked on her neck. It was her mother’s name.

Trapp thought Estepp fit the profile of a “circuit girl” — a sex worker who cycled through Anaheim, Oakland, Las Vegas and other prostitution hubs. Back at her desk, with the reek of the recycling plant still in her clothes, Trapp began faxing hotels in the resort district around Disneyland, trying to find the room where Estepp might have been staying. This didn’t bring any results.

The heart of the sex trade in Anaheim was a few blocks west — a mile-long north-south stretch of Beach Boulevard vice cops called the Track. It’s a wide street that bisects the city’s far western corner. To the north it spills into Buena Park, close to Knott’s Berry Farm. To the south, it turns into the city of Stanton.

Detectives decided to look here for Estepp’s last room, going block by block, motel to motel with her photo. During her years in sex crimes, Trapp became familiar with the landscape of 50-buck-a-night stucco fleabags with metal bars on their check-in windows — some of them kitschy midcentury motels that sprang up to capitalize on Disneyland traffic and had long since decayed.

Gas stations, doughnut shops, psychics, fast-food joints and an ever-shifting gallery of crooks, down-on-their-luck families, parolees and shuffling narco-zombies. She could guess the popular drugs by the gait of their captives, the streets cycling from crack to meth to bath salts to heroin.

For years, Trapp had worked undercover here when vice needed her as bait during John stings. At first, she dressed for the role in fishnets and heels. Then she shifted to a look more in sync with the streets, hair unwashed, flip-flops, tank top. She’d approach cars on the driver’s side, so she could see if the man behind the wheel had a gun, or a partner.

Hey, sugar, looking for a date? Sometimes she’d use a line from “Pretty Woman.” Customers were all kinds — a heart surgeon in a Mercedes, a tow-truck driver, guys in their 20s, one guy in his 80s.

Working undercover was a reminder of how dangerous it was for the women on Beach Boulevard. Sometimes men would grope her. She had the benefit of a wire on her body and a gun in her purse, and she stayed in character as she led them up to the motel room, where her partners were waiting inside to make the bust.

But there was often a moment when it took willpower not to flinch, just before she cracked the door, as she extended the key card thinking, “Open, open!” At that moment the man would stand right behind her, his hand on her lower spine, his breath on the back of her neck.

::

Detectives quickly discovered that Estepp had been staying in Room 217 of the Anaheim Lodge on Beach Boulevard. She had checked in but never returned. There were no signs of violence in the room, suggesting to Trapp that she had been killed elsewhere.

Management had kept some of the belongings Estepp had left behind, and detectives found more in a drawer:

A Hello Kitty purse. A Greyhound ticket from Oklahoma to California. Contact lens solution. A stack of $730 in cash, suggesting Estepp had had a profitable run on the street. A bag of Lifesavers. An Oklahoma ID card, with a dimpled face like a small-town beauty-pageant winner, the skin as unlined as a teenager’s.

The next day — the day she officially became the lead detective on the case — Trapp was on the phone with Estepp’s mother, who couldn’t understand why her daughter wasn’t answering her phone.

“When’s the last time you saw her?” Trapp asked.

“A week ago,” said Jodi Estepp-Pier. As far as she knew, her daughter was still at home in Oklahoma.

Trapp needed basic information, but the chances would plummet as soon as she told her. So when Estepp-Pier asked if her daughter was alive, Trapp sidestepped the question.

Did she have her daughter’s cellphone number? She needed it to get a warrant for her phone records.

The mother insisted: What was this about?

“I’m sorry to inform you that yesterday your daughter was found deceased,” Trapp said, and then she was listening to the mother screaming, and the line went dead. When Trapp got her on the phone again, Estepp-Pier asked, “Are you sure it’s my daughter?”

Did she have any tattoos?

“She has my name on her neck.”

::

Trapp learned that there had been a man in the victim’s life, and he became a suspect immediately. He was an Oklahoma gangster who called himself “Menace.”

He was the father of Jarrae Estepp’s 2-year-old son, and — according to her family — had been acting as her pimp. Her mother said they met when she was a 17-year-old high school student, and “she was just sucked into his lies and manipulations.”

She said Menace would urge Jarrae to go to Southern California to work the streets. It was where the money was.

When Trapp looked at Estepp’s phone records, she found Estepp had exchanged more than 100 calls or texts with him on the day she disappeared. “It was very apparent, the control that he had over her,” Trapp would say. “Constant, constant communication, and that’s very typical between a pimp and his girl. Complete and total control.”

Trapp got him on the phone. She begged for his help. He insisted he was neither Jarrae’s boyfriend nor pimp. “I got a female,” he said. “That’s just the mother of my child.”

He was not the killer — his phone records proved he’d been in Oklahoma — but he would soon receive a 15-year prison term on unrelated charges of racketeering, for his involvement with an Oklahoma branch of the Crips.

Trapp told Jodi Estepp-Pier she would find who had killed her daughter. The mother did not especially trust cops, but Trapp said, “I give you my word.” She was thinking of how cruelly Estepp had been thrown away. Every murder was ugly, every murder was a hole in the universe, but this reflected a cold-heartedness that was hard to fathom.

::

When Trapp got her second-floor desk in the homicide unit of the Anaheim Police Department a few years earlier, there was a sign taped up nearby.

“You can’t stop love,” it said.

It was the voice of weary experience, the bitter takeaway from too many murders and suicides precipitated by some twisted enslavement of the heart. It referred to the derangements of jealousy. It referred to victims who refused to testify against their abusers. It referred to people trapped in predatory relationships.

“A young girl in a fight with her mom, wants to run away, next thing you know ...,” Trapp would say.

In sex crimes, Trapp met a 17-year-old girl who had been impregnated by her pastor. Trapp remembered how hard it was to untangle the girl’s feelings of love from her sense of violation.

Every detective drew from a well of personal experience, and Trapp’s late teens had given her a sense of how easy it was for one bad choice to compound another, when the circumstances were right.

Back when she was still Julissa Rios, she was growing up with her parents and a younger brother in a spotless yellow house on Westmont Drive in central Anaheim. She had Sylvester Stallone and Steven Seagal on her wall.

She was working as an Anaheim Police Explorer, lining up for drill inspection at police headquarters and absorbing everything she could about police work. At 16, she sneaked out of the house to meet a boyfriend. “Rebelde,” said her mother. Rebellious. She kicked her out of the house.

Julissa Rios was a proud, headstrong girl, so she grabbed a red suitcase and said, “Fine!”

She got a job at a yogurt shop and crashed with friends. After a while she found herself living with a guy twice her age. He had money; he said he loved her but wanted to control her.

Once, when she returned from an outing with the Explorers, she found he had scissored up her clothes. He hadn’t wanted her to go; this was his way of punishing her. During that period, she didn’t talk to her mom. She kept in touch with her dad, who was her best friend and idol. He never judged her. He kept saying, “Come home, mija, everyone misses you.”

When her father learned that her grades had plunged from A’s to Fs at Savanna High School, he turned to Rick Martinez, the cop who ran the Explorer program, and said: Please do something for Julie. Martinez gave her a come-to-Jesus speech: Pull it together, or you’re out.

At a serial killer’s trial, a Times reporter met the homicide detective at the center of the case — and found a story of tenacious policework and obsession.

The thought of not getting to be a cop crystallized the stakes, and she made a choice. She left the older guy. She packed up her red suitcase and moved back into the yellow house.

“I got a chance to live,” she would say. She got her grades up and got into the police academy, where she was one of three women to graduate in a class of 26.

Julissa Trapp would come to speak of her teenage years as an abyss avoided. She’d say police work saved her; family saved her; some kind of grace she didn’t understand saved her.

::

On the fourth day of the investigation, Trapp stood in the medical examiner’s office as Jarrae Estepp’s body was autopsied. It was a glimpse of how brutal her last hours must have been. She had a bite on her right arm, bruising on her face and neck, signs of sexual assault. A tampon was recovered from her body and sent to the lab, in case it held an attacker’s DNA. Metal shavings were tweezed from her mouth.

Trapp and her partners, J.D. Duran and Bruce Linn, quickly became what they called “garbologists.” Republic Waste Services supplied a list of pickup locations that fed into its plant. There were hundreds of sites, along trash routes that snaked through Anaheim and nearby cities.

Soon dozens of cops were fanning out to find the Dumpsters. Trapp told searchers to look for the kind of shredded blue tarp the body had been wrapped in. Residential-construction debris. Metal shavings.

Meanwhile, detectives canvassed Beach Boulevard with Jarrae Estepp’s photo and talked to what Trapp called “every cretin and zombie” who prowled the area. Estepp’s cellphone records showed her last contacts, and this led them to a factory worker who had called her at 7:08 on her last night alive.

More from Christopher Goffard

Trapp put a team on the man. He was in his car with his wife when police pulled him over. He said he had paid Estepp $40 for sex in her motel room, but had left her alive. He volunteered his DNA; Trapp did not think he had the feel of a killer.

They found another of Estepp’s possible customers. He admitted that he had met her, but had changed his mind about the sex. He volunteered his DNA; he didn’t have the feel, either.

All day long, cops were coming by Trapp’s desk to drop off USB drives with surveillance footage of trash bins. She had asked them to collect any footage they could find, and fast: Cameras automatically erased after a week or two. She studied it. It was tedious work. Nothing.

::

There is a little gathering spot near Trapp’s desk with a deluxe De’Longhi coffee maker and a sign that says “10% Cafe,” a name whose origins are secret department lore. It’s a kind of shrine to colleagues past — crowded on a mantel is a motley cluster of beer taps that belonged to detectives who have worked homicide and moved on. Coors Light. Newcastle. Goose Island.

Every member of the homicide team got a unique beer tap, even teetotalers like Linn, and it went up on that detective’s cubicle wall in rotation so the supervisor could tell at a glance who was “on tap” for the next murder. Trapp’s is labeled Dead Guy Ale, an Oregon brew, and when she leaves the unit someday it will join the others on the mantel.

It was here, around Day 5, that Det. Mark Lillemoen suggested what seemed a wild idea: Why not run the GPS tracks of parolees on Beach Boulevard around the time Estepp disappeared?

Trapp thought it was impractical, with so little else to go on: The list would be massive, the block a cauldron of parolees.

Around the same time, Trapp’s supervisor asked her to meet with detectives from Santa Ana and Newport Beach. Both cities had open cases on missing or murdered women. Trapp was skeptical. She had so much else to do, and it didn’t strike her as the best use of time at this harried, pedal-to-the-metal stage in the investigation.

Trapp had not ruled out the possibility of a connection between Estepp’s death and the disappearances of three women in Santa Ana, starting five months earlier. All of the women had been working as prostitutes. But it struck Trapp as a far-fetched possibility; the odds pointed to someone who knew Estepp as her killer. A serial killer was statistically unlikely.

The prosecutor assigned to the case, Larry Yellin, seemed equally skeptical when she informed him of the meeting.

“Yeah, OK, Jules,” Yellin said.

Near the beginning of the third week, after so many dead ends and ruled-out suspects, the forensics lab called.

They had examined the tube of acrylic sealant found near the body. Linn’s hunch had been accurate: It did have a readable fingerprint. What’s more, the print matched a local man whose prints were on file.

He was 32, a window installer with a minor record for driving without a license. He lived at a mobile home park near 1st and Bristol streets in Santa Ana, not far from where some of the women had last been seen.

Trapp called him. She arranged to come by in the late afternoon when he got home from his shift. She didn’t say why.

The man stood at his doorway in Santa Ana, looking nervous. He had rough hands and a laborer’s stocky build. He was in dirty work clothes, just back from his shift at Hardy Windows.

Anaheim Police Det. Julissa Trapp had just handed him a card that said homicide. Now she showed him a photo of a tube of acrylic sealant. Could he account for his fingerprint on this particular tube, found near a body at a trash-sorting plant?

The man looked puzzled. This tube? They went through them all day long. When they finished a window-installation job, they trucked the trash to the alley behind their shop in east Anaheim. This must have been castoff from a recent job.

How did he know?

We never throw away trash at a customer’s home, he said.

Trapp had another question. The shredded blue tarp around the victim’s body — did he recognize it?

Yes, he said. It was the kind of tarp they used to protect windows during transport.

::

For weeks she had been searching for the bin where the victim’s body had been dumped, studying trash routes from the county’s vast suburban tracts to Disney’s Grand Californian Hotel.

And now, late in the afternoon of the 15th day of the investigation, Trapp and her partner, Bruce Linn, found themselves pulling up to Hardy Windows in the palm-fronted industrial park at the intersection of Cosby and La Palma.

The area was block-to-block woodworking and metalworking and auto body shops, the kind of place desolate of light and people after hours. Remote from schools or parks, it was known by police as one of the crowded city’s hidden pockets where transient sex offenders slept in bushes and cars.

Trapp went to talk to the window company. Linn went to the alley. Inside the trash bin, he saw the kind of distinctive blue tarp that Jarrae Estepp’s body had been partly wrapped in. He called for Trapp. Trapp saw it, too. They exchanged a glance; both knew.

“Dude, this has to be it,” she said.

Canvassing the area, Trapp learned that a man was living in an old Lindy camper at the site. “You might want to look at him,” a business owner said. The camper-dweller worked for Boss Paint & Body, across a narrow alley from Hardy Windows. She glimpsed him: a bland-looking white guy in glasses, of medium height. She noticed him noticing her, too.

But right now there were other tasks. A few days back, a detective had suggested checking the court-ordered GPS ankle bracelets of parolees on Beach Boulevard around the time Estepp had disappeared there.

Given the number of paroled sex offenders on that stretch of downmarket flophouses, it had seemed unrealistic. But now police knew where Estepp had been dumped, 12 miles away. Now they had two geographic points.

Had anyone been in both spots during the relevant times? Trapp thought it just might work. She called the sex crimes detective who had access to the monitoring system and asked her to run a check.

It turned out there were 10 known sex offenders near the intersection of Beach and Ball when Estepp disappeared there. And there were 23 in the industrial area where her body was dumped. One person was at both spots. His name was Franc Cano.

::

Cano was 27, 5 feet 2, a state parolee who had served prison time for molesting a niece. He lived in a Toyota van near the window shop. He glared coldly in his mug shot, his expression nearly a snarl, but in other photos he looked almost boyish. This was not the suspicious-seeming Caucasian man who lived in the camper — Cano was Latino, much smaller and much younger.

Trapp thought of the three missing women from Santa Ana and wondered if they were connected. She remembered that detectives in the nearby city had gathered the last known cellphone coordinates of the missing women. She called the detective who was working the case. He hurried over with the cell records.

“Let’s load up your girls,” she said.

They gathered at Linn’s cubicle on the second floor of the Anaheim Police Department. Linn had a map of Santa Ana up on his computer screen. He plugged in the intersections where the women had disappeared; another detective checked them against Cano’s ankle monitor.

Kianna Jackson, Harbor Boulevard and McFadden Avenue, 3:09 p.m., Oct. 6, 2013.

“He’s there.”

Josephine Vargas, 1st Street and Tustin Avenue, 7:10 p.m., Oct. 24.

“He’s there.”

Martha Anaya, 1st Street and Grand Avenue, 6:26 p.m., Nov. 12.

“He’s there.”

A sex-crimes detective was familiar with Cano. He was known to spend time in the company of another sex offender, Steven Gordon. Gordon was 45, an auto detailer at Boss Paint. He would have easy access to the window shop’s trash bin.

Trapp pulled up Gordon’s photo. It was the man from the Lindy camper. He too had worn a state-issued ankle monitor. They checked his GPS coordinates. They matched the last known whereabouts of Jackson and Vargas, but puzzlingly did not link him to Anaya and Estepp.

Did Gordon commit two murders with Cano but not participate in two others? It didn’t make sense.

Trapp learned that Gordon’s state parole bracelet was removed the day before Anaya disappeared. But soon he was wearing a federal monitor, and when she checked, she discovered its record corresponded to Estepp’s abduction site.

It was April 2, 2014, the 20th day of the investigation. For Trapp, it had begun with a search for one woman’s killer. Within hours it had become a serial murder investigation, which was rare enough, and now it was something rarer still.

She called the prosecutor, Larry Yellin.

“We have two of them,” she said.

::

There was a basic enigma at the heart of the Gordon-Cano relationship. What exactly was its nature? Who was the commanding figure? If both were killers, were they involved in equal measure?

Studying police and parole and probation reports, Trapp formed the impression that Cano was the more timid of the pair, Gordon the more seasoned convict.

On Gordon, 17 years older and 5 inches taller than his friend, the reports were ample. He had been in and out of lockups all over California, and drifted between jobs. Disneyland cook. Newspaper deliveryman. Meatpacker. Cemetery handyman.

In 1992, he had been convicted of molesting an underage nephew and received a three-year sentence. By August 2001, Gordon was married with a young daughter, but his wife grew scared of him and got a protective order. He disguised his car with a teal-green paint job, and waited outside her Mormon church in Riverside.

He forced his wife into the car, and thrust a Taser in her face. She watched the electricity jump from prong to prong. He grabbed her cellphone and threw the battery out the window. At a Super 8 Motel, he handcuffed her and told her he would release her if she had sex with him one last time.

‘If someone calls me a rapist, I’m going to punch them.’

— Steven Gordon

This is how an evaluator summarized Gordon’s self-exonerating account: “It was consensual because she had sex with me with the condition that I would take her home.” A jury convicted him of kidnapping but acquitted him of rape. He blamed his ex for ruining his life. He had just wanted to be with his daughter, he said.

In recent years Gordon had been working for Boss Paint and checking in with parole evaluators, who found him hot-tempered, with a penchant for deceit and con artistry. “I have always had an attitude problem since I was 5 years old,” he told one.

Gordon hated the idea of group therapy with sex offenders. “I don’t want to be with those losers and I don’t want to hear their stories about molesting kids. I didn’t rape my wife,” he said. “If someone calls me a rapist, I’m going to punch them.”

His relationship with Cano, according to parole reports, was marked by repeated lawbreaking. In October 2010, the pair cut off their GPS devices and got on a Greyhound bus headed to Talladega Superspeedway in Alabama. They were arrested two weeks later at a nearby Army depot. They got five months in prison and were soon back together on the streets of Anaheim.

In April 2012, police came upon Gordon working on his car with Cano behind Boss Paint. When a parole agent tried to take them into custody for associating — a violation of their parole terms — Gordon announced that he was going to run. “What are you going to do about it?” he taunted.

Gordon ran, and Cano followed. For a second time, the men cut off their GPS monitors and fled the state. They went to Las Vegas, where police caught up with them at the Circus Circus casino. This time, they were gone about three weeks. The escape earned them a few months in prison and federal probation.

Now they were free again, both homeless denizens of the industrial area around Cosby and La Palma. And they were still frequently in each other’s company, in violation of their parole — a fact that had somehow escaped the notice, or concern, of innumerable agents and the vast monitoring capacity of state and federal bureaucracies assigned to watch them.

::

Round-the-clock surveillance began right away, with Trapp carrying two radios, one for each man. Teams of undercover cops in dark-windowed cars cycled in and out of the industrial zone where the men lived, a location that made it almost impossible to watch them without drawing attention. It was clear who belonged and who didn’t when the shops closed and the garage doors were pulled shut for the night.

From the surveillance teams, Trapp got a picture of the suspects’ daily rhythms.

Gordon spent almost all his time around Boss Paint, where he wandered with his little black dog, Bear, and slept in his Toyota 4Runner. Cano slept nearby in his Toyota van, and sometimes watched the dog. He would meet his parents at a nearby Carl’s Jr.

The crime lab came back with the news that two men had contributed DNA to semen found in Estepp’s body. Now police needed DNA from Gordon and Cano to compare it against. Because of their records, their DNA profiles were in the state database, but it might take weeks to access them.

Trapp thought they might get a faster match if they could get fresh, surreptitious samples, and with Cano this proved possible: The team following him watched him throw away a piece of chewing gum. They bagged it and whisked it to the lab.

Days passed, and surveillance grew increasingly tricky. Both men seemed aware they were being followed. Gordon was avoiding his RV, and Trapp worried he would sneak inside to destroy evidence; maybe, like other serial killers, he kept mementos.

Meanwhile, Cano was sleeping in the surrounding bushes and parking his van at his mother’s house in nearby Garden Grove. At one point he walked into the lobby of the Anaheim Police Department and complained that strange men in cars were stalking him. He had written down the license plates.

By now, Trapp was the center of a law-enforcement juggernaut comprising 75 cops from seven agencies: Anaheim and Santa Ana police, county probation, state parole, federal probation, U.S. Marshals, FBI.

The main aim of the surveillance, even if the suspects were on to it, was to ensure they didn’t slip away or kill. “Where are they?” Trapp asked her radios. “Do you have eyes on them?”

Trapp’s husband had gotten used to her being gone. She’d get home after a 16-hour day and microwave the long-cold dinner he’d made her and wolf it down.

‘I can’t screw this up ... You do not want to be the detective that lets two serial killers escape.’

— Det. Julissa Trapp

If he was still awake, they might exchange a few words across their maple wood-topped kitchen island. He’d ask about her day. Where to begin? With her mounting dread of hearing the words “we lost them”?

The pressure and fatigue grew by the day, and so did the risk of continuing the surveillance. Was she making a mistake by letting it go on?

“I can’t screw this up,” she told her husband. “You do not want to be the detective that lets two serial killers escape.”

She kept the radios on her nightstand. She couldn’t sleep until she knew the suspects were asleep themselves. Then she would wake in the dark to call each surveillance team.

Where’s Gordon?

Still in his RV.

Where’s Cano?

Jules, he’s still in the bushes. Go to sleep.

Beyond the surveillance teams, police had the advantage of the suspects’ ankle bracelets. The Veritrax system pinged their locations every minute. But if the men cut off their monitors again, they would have a head start. They could cut through the fence bordering the lot where they spent their time. In the solid dark, they might slip past the police perimeter.

Did police have enough to arrest them? On April 9, 2014 — Day 26 of the investigation — the evidence grew stronger still. The DNA from Cano’s gum matched one of the profiles from Estepp. And they received the results of a warrant seeking the suspects’ text messages.

Trapp was at the courthouse, trying to get a wiretap warrant signed, when Bruce Linn called from the station with this news.

Jules, you need to get back here, he said. You won’t believe it.

::

The men had tried to erase their texts, but MetroPCS had retained an electronic record, and now Trapp was studying hundreds of them going back to the beginning of the year. They revealed what Gordon and Cano talked about when they thought no one was listening, an admixture of the prosaic and hideous.

They talked about whether to heat up the pizza or do Taco Tuesday. They talked about Gordon’s dog, the Anaheim Ducks, the races at Daytona. They traded sexual fantasies; they bantered as lovers.

In February, amid the spate of disappearances, Gordon wrote: “I don’t want to have to hurt the cat so let me see if I can get some then we will decide … She is gonna fight scream yell kick bite.”

Cano: “I got the tape ready.”

Weeks later, apparently in reference to another woman, Gordon wrote: “When the cat knows it ain’t leaving it might try something.”

There was a flurry of texts on the night in March when Jarrae Estepp was abducted.

Gordon: “I can’t hurt this cat. I just cant.”

Cano: “You’re gonna get your hands dirty… Get rid of her.”

Gordon: “How.”

Cano: “Happy hand.”

Gordon: “Can u do it?”

Cano: “I thought the next one you were going to go at it.”

Gordon: “I can’t. Cat is beautiful.”

A while later, Gordon wrote: “Bye-bye, kitty.”

The texts, which would later be introduced in court, dispelled any doubt in Trapp’s mind that the men had worked together to carry out the crimes. The texts showed the men had known they were being watched almost immediately.

When they were apart, one man would get nervous that police had arrested the other. Cano kept shooting Gordon questions to confirm his identity.

“What’s my favorite NBA team”

“Clippers”

“Before coming to oc … what city did I grew up in”

“l.a.”

Trapp still wanted a DNA match linking Gordon to Estepp’s body, but he sounded ready to run.

Gordon: “When I leave u r a fool if u stay!”

Cano: “Maybe … but I’m staying.”

Gordon: “Well I’m outta here with or without u. I’m going to check the computer 4 a nice place to go.”

Cano: “R u crying…cuz I said no”

Gordon announced he planned to commit suicide. “Ive decided 2 end it all once I find bear a good home”

Cano: “Is that why you said te amo last night”

Gordon: “I guess.”

Cano: “Be honest are you really going to do it”

Gordon: “Considering it yes.”

Cano: “You don’t want to though.”

“I do & don’t,” Gordon texted, “but my future looks bleak”

Cano: “Tell bear I said good bye and many licks…and you find him a good home. Te amo friend always … goodbye … or should I say goodbye for iternity.”

Gordon made another plea: “Lets get out of Dodge while we can”

::

It was time, Trapp decided.

“Pick them up.”

Her department had plotted out a strategy, with the help of the FBI. They would arrest the two men simultaneously and put them in separate interrogation rooms. Trapp would move between the two rooms questioning them, playing them off each other.

About 6 p.m. on April 11, the team watching Franc Cano converged on him as he was getting on a bus. He was handcuffed and driven to the interrogation room.

Trapp wanted to interview him alone. One interrogator, one suspect — that was ideal, in her view, to create the intimacy necessary for a confession. She opened the door and walked inside. She introduced herself and made some small talk. She tried to ease him into a conversation.

Cano didn’t bite. He wanted a lawyer. He struck her as colder than she had believed, not meek and timid. The interview ended quickly.

Trapp stepped into the hall and picked up the radio, to find out the status on Gordon’s arrest. She learned that it hadn’t happened yet — there was a problem.

Despite the best efforts of police to prevent him from finding out, Gordon somehow grasped that Cano had been arrested. He was firing questions at Cano’s phone, and Bruce Linn was doing his best to answer them, trying to convince him that Cano was still free, trying to trick him into a confession. But it wasn’t working.

And now cops had surrounded Boss Paint & Body, with Gordon holed up inside in the company of a co-worker. Police were calling it a barricade situation, but no one had actually made contact with him yet to demand he surrender. So Trapp and an FBI agent called him. Gordon said he wouldn’t come out. Now it was a real barricade.

Around 8 p.m., Gordon grabbed a box cutter and jumped on his bicycle. He pedaled hard through the parking lot and sped onto La Palma Avenue. A surveillance truck clipped his bike and he went flying. He was taken to a hospital. No serious injuries.

He would be driven to the station the next morning, and Trapp would face him alone. Maybe she would succeed with him where she had failed with Cano. Getting Gordon to talk might be the only way of understanding exactly how the partnership with Cano had functioned … and what had happened to Estepp … and what had happened to the three missing women.

Trapp had been working nearly nonstop for weeks, and the fatigue was showing.

“You look like crap,” said J.D. Duran. “Go get some sleep.”

At home she poured herself a glass of wine, trying to relax, but her thoughts were racing. Her husband, Eric, was home and sleeping. A SWAT commander, he had been en route to the action when Gordon surrendered. She slept little, and rose before dawn.

She watched the killer for a long time, waiting for exactly the right moment. So much depended on the little things, like making him believe you were not in a special hurry to talk to him, even if you had been able to think of little else for the last month.

Julissa Trapp stood in her sergeant’s office at the Anaheim Police Department, cradling what might have been her 100th cup of coffee since the case began, huddled with a team of other cops around the closed-circuit monitor with its bird’s-eye view of the interview room down the hall.

On the screen, Steven Gordon’s face was a pale smudge. He was a slight-looking man in his mid-40s, hunched forward slightly in a wheelchair as the minutes passed, maybe just a bit chilly. The thermostat had been turned down to the mid-60s in there, so that at the right moment she could offer the illusion of friendship in the shape of a blanket.

Around her department, Trapp was considered a master interrogator. She honed the art of what could only be described as weaponized empathy. Once, she interviewed a man accused of molesting his 8-year-old niece. “I think you understand me,” the man had said, and began caressing her hand as he confessed. She resisted the urge to yank it away; the man went to prison.

To walk into an interrogation room was to play a character, she liked to say, and for Steven Gordon, she’d have to figure out exactly the right one. A mother? A sister? A female friend willing to listen? In her closet that morning, she had debated carefully about what color to wear, and had chosen an emerald green top calculated to project approachability — but also strength.

She had decided that she would go in unarmed, and would sit as close to Gordon as possible, without the barrier of a desk between their bodies. His hands were free, and he could lunge at her. Would her reflexes be sharp enough, considering she hadn’t slept much in weeks? It might be 15 or 20 seconds before help came. She was willing to take the chance.

Around 10 a.m., after keeping Gordon waiting for 30 or 40 minutes, she announced, “Here goes nothing.” She walked down the hallway to the interrogation room. She paused outside. She crossed herself, and walked in.

“Hi, Steven,” she said.

Gordon’s face was bland, forgettable, without outward menace. He said he was sore — a surveillance truck had knocked him off his bicycle as he tried to flee the day before — but otherwise fine.

After reading him his Miranda rights, Trapp opened with a standard gambit — she gave him a chance to blame his co-defendant, Franc Cano. She was not going to tell him that Cano had refused to speak to her.

“I honestly feel that you’ve kind of been given a dirty deal on this whole thing,” Trapp said.

“Is this where the good cop/bad cop comes into play?” Gordon asked.

A longtime felon, Gordon seemed to grasp the game immediately. Trapp knew it would be over in a second if, like Cano, he lawyered up. Still, for reasons she didn’t yet fully understand, he seemed willing to participate.

“You were very upset last night,” she said.

“Should’ve just let them shoot me instead of running.”

“You know that’s not true.”

Hundreds of years of experience were crowded into her sergeant’s office, watching Trapp work — local cops, state agents, FBI. But she was glad to be alone in the room. To her, one suspect, one detective was ideal. She wanted as little space between herself and the killer as possible. Closer was better — but it would give him a chance to study her, and she felt his pale blue eyes moving over her face, probing for weakness or deception or hints of judgment.

The killer soon gave her an opening. He wanted to talk about how much he hated his parole and probation officers. He had tried desperately to get authorities to remove his ankle monitor, but they kept hassling him, lying about him, getting him violated on claims he had associated with Cano.

Even as he raged about this, he admitted that he and Cano had cut off their monitors twice and fled the state — once to Alabama, in hopes of seeing a Nascar race, and once to Las Vegas, where they walked the Strip and rode roller coasters. Gordon continued in this vein for a while, there in a room that was slightly chilly by design. At about the 15-minute point, Trapp slipped this in:

“Are you cold? Did you want a blanket?”

“Yeah, if you don’t mind.”

He wrapped himself in the blanket and, as the interview progressed, seemed to retreat further and further into it. Gently and patiently, she elicited more details about his life.

He’d been working at Boss Paint & Body for about three years. He said he had a daughter, and Trapp knew that in the early 2000s, when the girl was 4, Gordon had kidnapped her along with his estranged wife, whom he had threatened with a Taser. He was charged with raping his wife during the abduction, but he emphasized that a jury had acquitted him of the charge. And, he insisted now, he had never hurt his daughter.

“I know you didn’t,” Trapp said. He had just been trying to keep his family together.

“Just didn’t go about it the right way,” Gordon said.

Trapp saw an opportunity, but it meant gambling a sliver of painful personal information. Now and then, she would surrender personal details for use as interrogation-room currency. A lot of cops are loath to do this — they don’t want to give a bad guy any opening to taunt and menace. They don’t wear wedding rings on the job, or carry their kids’ photos, much less share their deepest griefs. Trapp was different, closer in philosophy to a novelist or actor for whom wounds are material.

“I get where you were coming from,” she said. “I unfortunately can’t have children, but I can only imagine what it would feel like.”

Building on this authentic detail, she added a fictional flourish.

“I tried to adopt and the kid kind of got taken from me, and I didn’t think I was gonna make it,” she said. “So I can’t even imagine what it felt like for you to be losing your daughter.”

She told him he was a caring person.

“Steven, a mistake was made and you got pulled into this,” she said.

She told him they needed to get to the truth together.

“What you say your name was?” he asked.

“Julie.”

“Julie?”

“Yeah.”

“I can’t talk to you.”

“Would you rather talk to somebody else?”

“I don’t want to talk to anybody.”

Gordon said that every attorney he’d ever had had screwed him over. From now on, he’d represent himself. And so, about 50 minutes into the interview, he was lawyering up — and the lawyer was himself.

Anaheim Police Det. Julissa Trapp interrogated suspect Steven Gordon for 13 hours.

Trapp thought: It’s over. That’s that. There would be countless unanswered questions. But now Gordon said he needed some air. Trapp and her partner, Bruce Linn, wheeled him outside to the patio, where Gordon said this:

“I’ll tell you guys everything you need to know as long as I get the death penalty. Other than that, I’m gonna be quiet. That’s the way it’s gonna be.”

He wanted it in writing from the district attorney. He didn’t want a trial; he didn’t want appeals.

“None of that crap,” he said.

There was zero chance the state of California would grant Steven Gordon’s demand for a speedy death. It had been more than eight years since the state last executed anyone, in 2006, and that prisoner had waited on death row for 24 years.

But to tell Gordon this straight-out might shut him down, and so Trapp played for time, and sent for Assistant Dist. Atty. Larry Yellin. It was Saturday morning, and Yellin was on a softball field. As they waited for him to show, Trapp made small talk. Gordon was a fan of country music. So was she.

“My friends used to make fun of me because obviously I grew up in Anaheim and I’m Mexican so I guess I should be listening to like hip-hop and stuff,” she said. “And no, I started listening to country when I was 16. But that’s when like Garth Brooks was big, and Trace Adkins and Faith Hill.”

The conversation meandered to cars. She said she wanted a 1976 Chevy pickup but didn’t know what she’d be getting into, a pose of cluelessness designed to flatter him.

“Being a chick, not knowing a lot about cars, I think I need one that’s, like, already done, you know, because I don’t know how to work on cars, and I think I’m gonna get screwed if I try to repair it little by little,” she said.

“You’re not gonna paint it pink, are you?”

“No, no, no, I think red.”

“Cops love red.”

She asked him if he had many friends besides Cano.

“Don’t hang out with anybody, really,” he said. He was fixated on suicide. If he was to do it, he’d put a hose in the tail pipe and turn on some music.

“If somebody wants to end their life, what does anybody care?” Gordon said. “I mean, maybe that person is just that unhappy.”

At lunchtime she had Mexican food brought in. Gordon said he had met Cano in 2010, at the parole office. Cano, who was 5 feet 2, had asked if he could sit down and charge his ankle monitor from an electrical cord.

“I’m like, damn, this guy is a kid,” Gordon said.

“And he looks a lot younger than his age, too,” Trapp said. “He can pass for a teenager.”

He said Cano was naive. He thought everyone was his friend. Once, at the parole office, Gordon had confronted a man who’d asked Cano what he’d done time for.

The anecdote told Trapp that Gordon felt protective of the younger, smaller man. She was not going to volunteer that she knew they were lovers.

Near the end of the fourth hour, Yellin showed. Gordon reiterated that he wanted the death penalty. He didn’t want those stupid anti-capital punishment groups dragging out his appeals and persuading stupid judges to keep him alive.

“How long am I gonna have to wait?” Gordon said. “If you’re gonna tell me 10, 50 years, I’m not gonna do that.”

Yellin said he would have to leave to research the question. It might take a while, he said — it was a Saturday, after all.

Alone again with Gordon, Trapp explained her philosophy about working homicides. Some of the victims were gangbangers, criminals, cold-blooded killers themselves. But to their families, they mattered.

“That mother hurts like any other mother,” he said.

Mention of mothers seemed to make Gordon think about Cano, and he began to cry.

“There’s a kid downstairs that needs his mom,” Gordon said.

In the middle of the fifth hour, she began to press him about the dead and missing women. She put photographs in front of him. Kianna Jackson. Josephine Vargas. Martha Anaya. Jarrae Estepp.

Gordon rearranged them in the order of their disappearance.

“I don’t know how or why it started,” Gordon said. “I picked up a lot of girls and I never did anything like this. I just paid them.”

He admitted that he picked up Estepp and took her back to what he called “his spot,” behind the auto-body shop. They had sex, he said.

“And she sprayed me in the face with Mace and I don’t know what happened after that. I went, I went crazy.”

“So what happened next?”

“I hurt her.”

“Can you tell me how you hurt her?”

“I strangled her with my hands.”

He said he picked up Kianna Jackson. They went back to his spot. They had sex. He strangled her.

“Did she go in a trash can?”

“They all did.”

She sensed him watching her closely — every tremor on a face she tried hard to make into a mask. More than once, he would stop his account to ask her what her expression meant. Nothing, she said. She pressed him to keep going. He said he strangled Josephine Vargas. He said he strangled Martha Anaya.

“Why won’t you tell me what trash can you put them in?” Trapp asked.

“What does it matter? For you, what does it matter?”

Near the end of their seventh hour, Trapp asked him why he had left Cano out of his account of the killings. Gordon announced that he was not an idiot — he knew Cano’s GPS tracks connected him to the missing women. His story began to shift, incorporating Cano but only as a passive observer.

Trapp told him that Cano said they had taken turns.

“I can tell you he’s lying,” Gordon said. Gordon had planned to take the blame if they ever got caught. “‘Cause he’s a kid.… He’s young, he still has a chance. I don’t. I don’t anymore.”

The conversation was a quietly protracted struggle for advantage, and she knew the outcome would be shaped by intonations, micro-expressions and her moment-to-moment ability to improvise skillfully. If she breathed too hard, he seemed to notice and clam up. He was sensitive to the slightest sign of judgment.

Gordon said that unless he talked, they had nothing on Cano.

“You don’t have proof other than me opening my mouth or you saying that Franc is talking to you. You have no evidence. I made sure of that, or you would’ve been there a long time ago.”

She kept asking where he had dumped the bodies, and he kept dodging the question.

“They’re never gonna be found, are they?” he said.

She said she would dig for them personally, even if she was only able to find bones. But she needed his help.

“Did they all go in the same trash can container? Or just different containers in that area?”

“Drop all the charges against Franc, I’ll tell you what you want to know.”

“I can’t do that. That’s not a decision I make.”

Gordon described a relationship with Cano that was not just protective but violently possessive. He’d once kicked Cano in the stomach when he found him with a woman. Once again, he denied that Cano had helped to murder Estepp.

“Not gonna tell on my friend,” Gordon said.

Finally, in the middle of their ninth hour, Gordon said he would tell her everything she wanted to know, on the condition he could see Cano.

“I just wanna know if he’s all right,” Gordon said.

Trapp said she would ask.

The 10th hour, time for dinner. She had Panda Express brought in. They ate together. He talked about how Cano didn’t seem to appreciate him.

“I tried so much to help that kid. And just like, took everything I did for granted. That’s how I look at it, you know?”

She asked him again where he put the bodies.

“Where I work,” he said finally.

This was an important breakthrough, but they were only partway there. She thought the key to breaking Gordon might be his relationship with his co-defendant. Something had struck her about her brief, abortive conversation with Cano the day before — Cano had shown little to no curiosity about Gordon’s plight. Gordon loved Cano more than Cano loved Gordon.

In the squad room, the FBI agent suggested: Why not tell Gordon that Cano refused to talk to him? Trapp thought that would devastate Gordon. She liked it. She thought it might work. She said: “Let’s break his heart.”

As their 11th hour together was ending, she risked the big bluff.

“Good news is my administration will allow it,” she said. “Bad news is Franc doesn’t want to see you.”

Gordon seemed dumbfounded.

“He wouldn’t refuse.”

“Well, you also said he wouldn’t talk, and he did. I’m sorry.”

Gordon stared into empty space as if crestfallen, and seemed to withdraw deeper and deeper into his blanket. He had just taken the blame for a series of murders for a man he loved, who in turn didn’t even want to see him.

The silence stretched for more than a minute, and Trapp knew better than to fill it. Finally Gordon cleared his throat, and as their 11th hour turned into the 12th, his love for Cano seemed to curdle before her eyes into rage and hate, and when he began to speak again, she knew the room was finally hers.

“Why don’t you tell me how you think it went down?” Gordon said.

Now, in his account, he and Cano were collaborating partners in a series of abductions, rapes, murders and cleanup jobs that grew more methodical and sophisticated as they progressed. They would cruise Anaheim and Santa Ana in search of sex from prostitutes. They knew women would be reluctant to get into a car if they saw two men inside, so one man would drive while the other hid in the back seat.

They would overpower the women and drive them back to the lot behind Boss Paint & Body, a place so dark and isolated no one would intrude. In Gordon’s 4Runner truck or RV, he continued, they would take turns raping the women and then hold out the false promise that they’d be released. All of the women cried and begged; some spoke of their kids.

He said Cano would strangle women while Gordon — at Cano’s command — punched them repeatedly in the stomach, to hasten their asphyxiation. He said Cano would strip the bodies and clip the nails and throw the bodies away. They chose the evening of trash pickups to do their work.

“Just take me back outside so I can make a run for it and you guys can shoot me,” Gordon said.

“I can’t do that. Thank you for telling me what trash can you threw them in.”

“I hope you find them.”

It was late. The nightly fireworks above Disney had boomed and faded. As the 13th hour began, she stepped into a hallway full of cops eager to congratulate her.

She brushed past them toward the bathroom. All day she had fought against emotion, bottled up every feeling that might threaten to flicker across her face. But now she stood at the mirror, her makeup gruesome under the sudden flood of tears.

She was heading back into the interrogation room when the FBI agent stopped her. Don’t let him see you like that, he said. Don’t give him a victory. Take a few minutes.

When she returned, her face clear, she conveyed no impression of the toll the interview had taken on her. She watched the forensic team enter to take Gordon’s prints and hair samples and DNA.

Soon there would be a news conference, with inescapable questions: How was it possible that two sex offenders with ankle monitors, under 24/7 electronic supervision, could have committed a series of murders? What went wrong?

But right now Trapp was thinking about how to recover the bodies of the missing women — a logistical nightmare, but at least she knew enough to get started. And she was thinking about something else Gordon had said — something she had tried hard not to react to. He had mentioned a fifth victim, a woman who had vanished so completely it had drawn no law enforcement notice at all.

“You’re missing one,” he had said.

The mountain grew relentlessly, 7,000 tons of garbage hauled up the switchbacks every day to be unloaded and crushed and pulverized. Matter dissolved into its atoms, urged along by science, and the mountain grew.

When she got to the top of the Olinda Landfill at Orange County’s northern tip, Det. Julissa Trapp thought it was possible, just maybe possible, to do what she and her partner had come for: Find the bodies of four murdered women they believed were buried somewhere on the 565-acre site.

They gave the landfill engineers the dates:

Kianna Jackson, vanished Oct. 6, 2013.

Josephine Vargas, vanished Oct. 24, 2013.

Martha Anaya, vanished Nov. 12, 2013.

Jane Doe, vanished Feb. 14, 2014.

The landfill engineers performed careful calculations, and told police where they would need to look. The bodies were probably somewhere within a three-acre range in a northwest section, 18 to 25 feet deep.

With growing dismay, Trapp watched the choreographed dance of the big machines — the unloading trucks, the shoveling dozers, the crushing tractors with steel-spiked wheels, all mobilized for war against inconceivable volumes of trash.

Trapp thought, “There’s just no way.” It was April 2014, and some of the bodies were already half a year down. Finding a single bone would be an extreme long shot.

In fall 2013, women began disappearing from the streets of Orange County. Read more about the cases that inspired Christopher Goffard’s new podcast, “Detective Trapp.”

The FBI said it had had no luck in similar efforts. It would cost at least $12 million — about a tenth of the Anaheim Police Department’s annual budget. And because nobody could be absolutely sure the women were here, they might have to search a second landfill 60 miles away. There would be no dig.

For Trapp, finding the women was about more than collecting evidence. She wanted to return them to their mothers. As she drove back down the mountain, she was already thinking about how she’d tell them.

::

As trial approached in State vs. Steven Gordon in late 2016, a schoolteacher friend invited Trapp to speak to her second-grade class in Riverside County. It was a welcome distraction from the grimness ahead. For this visit to Ronald Reagan Elementary School, she staged a crime scene based on the book “If You Give A Mouse a Cookie.”

To find the cookie thief, they had to follow clues — crumbs and mouse prints. She explained that her job was like that. She was a police officer, and a certain kind of police officer known as a detective, and a certain kind of detective who helped when people had died. She caught bad people.

The second-graders wanted to know: Had she ever arrested anyone? Yes. Had she used her gun on anyone? No. Was she afraid of the bad people? No.

There was a strange symmetry to it. She had been talking to a room full of students when her buzzing cellphone drew her into the case more than two years earlier.

Back in Orange County, pretrial motions were underway. Gordon was charged with four rapes and murders, though only one body had been found. As lead detective, Trapp would sit at the prosecution table next to Assistant Dist. Atty. Larry Yellin in Superior Court in Santa Ana.

Gordon’s conviction never seemed in doubt. He claimed to want the death penalty, and the evidence looked ironclad: texts, confession, ankle-monitor tracks, and DNA in Estepp’s body that the lab had matched to his.

The real question was how bizarre the trial would become, with an erratic and furious defendant determined to represent himself and driven by a logic only he grasped.

Steven Gordon the murderer might have wanted punishment, but Steven Gordon the lawyer wanted to punish the justice system he had long raged against. Trapp thought he was playing a power game, seeking ways to assert himself. This was his stage, and he had a surprise: He wanted his 13-hour confession suppressed.