Vera B. Williams’ family saved pennies and nickels to get by during the Depression. So her mother’s purchase of a “real chair” — neither stick-hard nor someone’s castoff but brand new and cushiony — was an extravagance.

“I don’t intend to work all my life and have nowhere to sit down,” the woman said after her young daughter demanded to know why she bought something she had to struggle to pay off in monthly installments.

After chastising her mother, Williams recalled, “I felt that terrible mixture of guilt and righteousness that a person — child or adult — feels in such a situation.”

Decades later, the painful memory became fodder for Williams’ late-life career as a prize-winning children’s author.

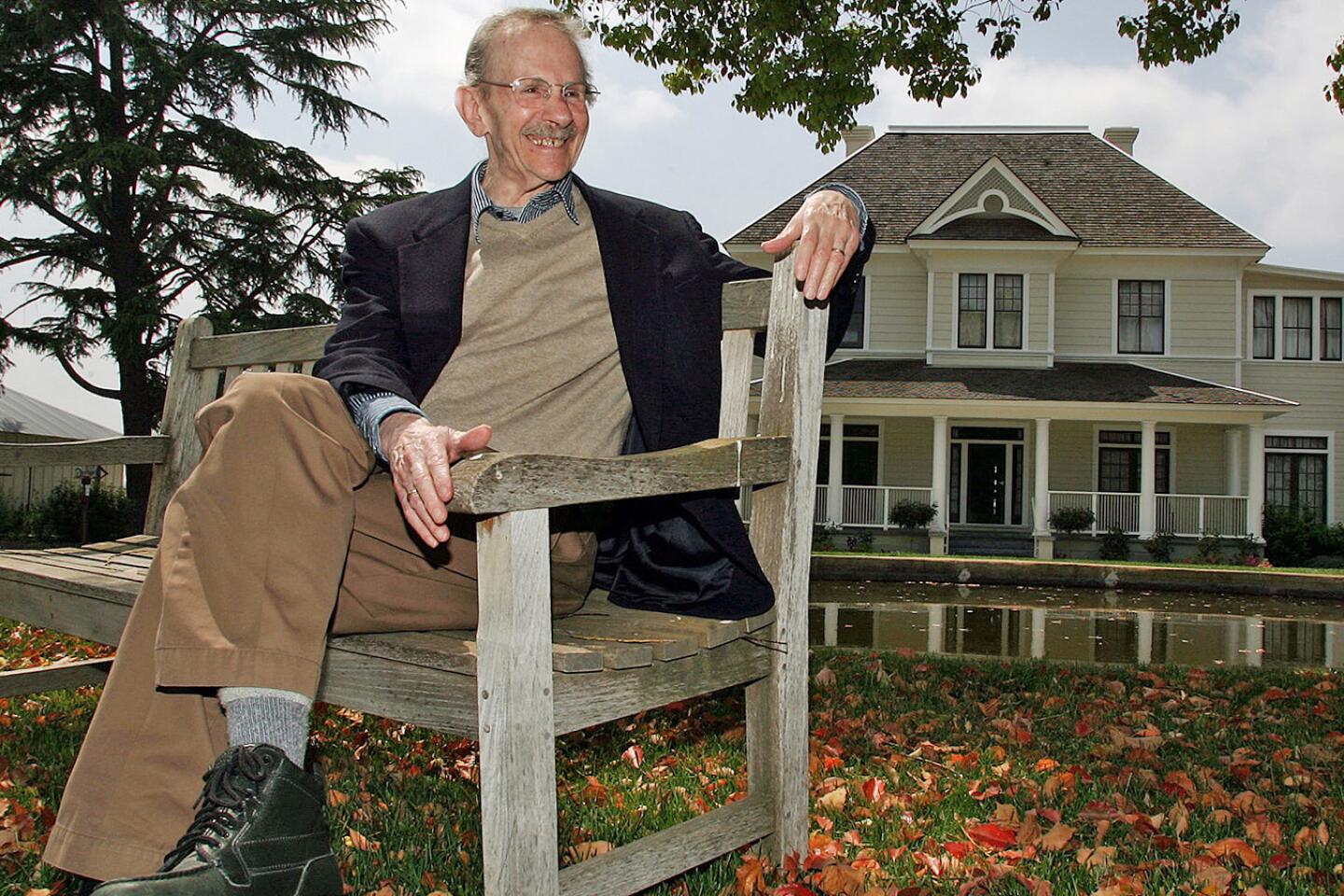

An educator and activist before she began writing stories that celebrated the resilience and creativity of women and girls from working-class backgrounds, Williams died Oct. 16 in Narrowsburg, N.Y.

A Los Angeles native, she was 88 and had ovarian cancer, her son, Merce Williams, said last week.

Williams wrote and/or illustrated 16 books, including “A Chair for My Mother” (1981) and “More, More, More Said the Baby” (1990), both of which earned prestigious Caldecott Honor citations.

In many of her books, characters grapple with poverty, absent fathers and other hardships. “Amber Was Brave, Essie Was Smart” (2001) was a sometimes wrenching, semi-autobiographical tale about two latchkey sisters whose mother worked long hours because their father was in jail.

Throughout her work, Williams depicted children of various hues whose parents were sometimes of a different ethnicity or race.

“Her books were full of exuberance and respect for children. She loved making books, and that love just comes out of the pages,” said Williams’ publisher, Virginia Duncan of Greenwillow Books, an imprint of HarperCollins.

Born in Los Angeles on Jan. 28, 1927, Williams was one of two daughters of Eastern European Jews. Her father, Albert, often was out of work and disappeared for a long stretch, possibly because he was in jail. Her mother, Rebecca, sent Vera and her sister, Naomi, to a Jewish orphanage for about a year, until Albert came home.

1/64

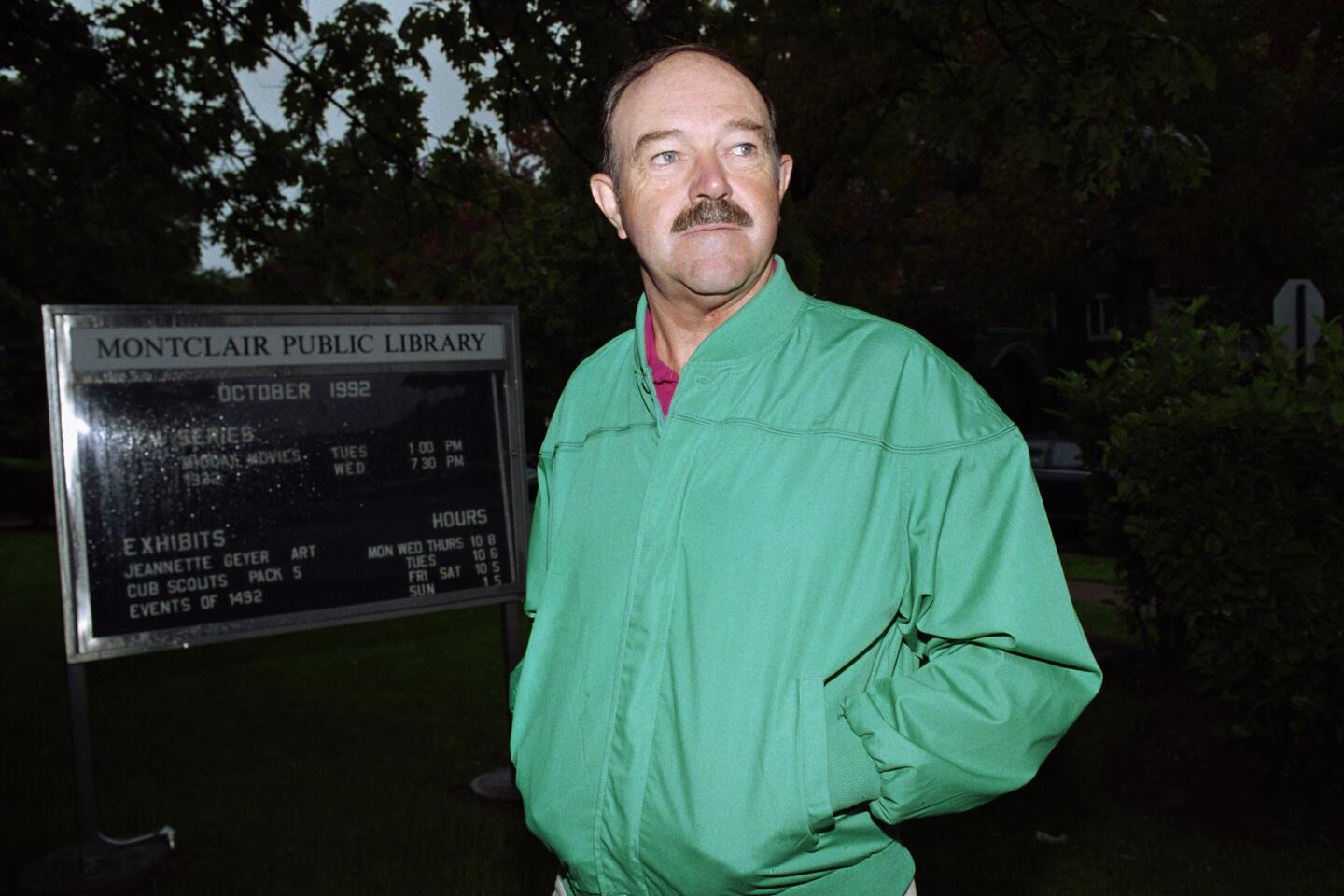

The former national security advisor helped craft President Clinton’s foreign policy from 1997 to 2001, when the administration carried out airstrikes in Kosovo and against Saddam Hussein’s forces in Iraq. He previously had worked in the State Department in President Jimmy Carter’s administration. He was 70. Full obituary

(Kevin Wolf / Associated Press) 2/64

The former South Korean president formally ended decades of military rule and accepted a massive international bailout during the 1997-98 Asian financial crisis. He was 87. Full obituary

(AFP / Getty Images) 3/64

The Scottish drummer replaced Ringo Starr as the Beatles’ drummer on their first single, “Love Me Do.” The song, all 2 minutes and 22 seconds of it, was a hit, but after the session, White never played with the Beatles again. He was 85. Full obituary

(Michael Brennan / Getty Images) 4/64

The legendary stripper and Bay Area institution helped introduce topless entertainment more than 50 years ago. She was 78. Full obituary

(Norbert von der Groeben / Associated Press) 5/64

The West German chancellor was known for shepherding his country through tough economic times, pushing it closer to eventual reunification with Communist East Germany and facing down a band of domestic terrorists. He was 96. Full obituary

(AFP / Getty Images) 6/64

The revered songwriter, producer, pianist and singer was a key architect of the early rock and R&B music that flowed from New Orleans to the national stage, an artist whose widespread influence led to his eventual status as a patriarch of the city’s fertile musical mash-up. He was 77. Full obituary

(Lawrence K. Ho / Los Angeles Times) 7/64

The Southern California custom-car legend created many of the most memorable and outrageous automobiles ever seen on film and television. He designed TV’s Batmobile as well as special vehicles for many of the biggest names in Hollywood, including Frank Sinatra, Sammy Davis Jr., Elvis Presley, Michael Jackson and John Wayne. He was 89. Full obituary

(Al Seib / Los Angeles Times) 8/64

The Irish-born actress was one of the biggest film stars of the 1940s and ‘50s. She more than held her own in her most heralded roles, even against as forceful a presence as John Wayne, with whom she made five films including the classic “The Quiet Man.” She was 95. Full obituary

(Harold Filan / Associated Press) 9/64

Chef Paul Prudhomme popularized spicy Louisiana cuisine and became one of the first American restaurant chefs to achieve worldwide fame. He was 75. Full obituary

(Bill Haber / Associated Press) 10/64

Filmmaker Chantal Akerman was frequently likened to Orson Welles, Jean-Luc Godard and Rainer Werner Fassbinder for her restless, broad-ranging style and the piercing intelligence she brought to both the formal and thematic elements of her work. She was 65. Full obituary

(Elisabetta A. Villa / WireImage) 11/64

In an era when few minorities of any kind belonged to Los Angeles’ social and civic elite, Marilyn Hudson was sometimes seen as the token black. The local civic leader broke barriers quietly at a time when racial militancy was in vogue. She was 88. Full obituary

(Marianne Diamos / Los Angeles Times) 12/64

Susumu Ito, a member of a Japanese American regiment that rescued another group of U.S. soldiers during World War II, went on to become a professor and researcher at Harvard Medical School. He was 96. Full obituary

(Katie Falkenberg / Los Angeles Times) 13/64

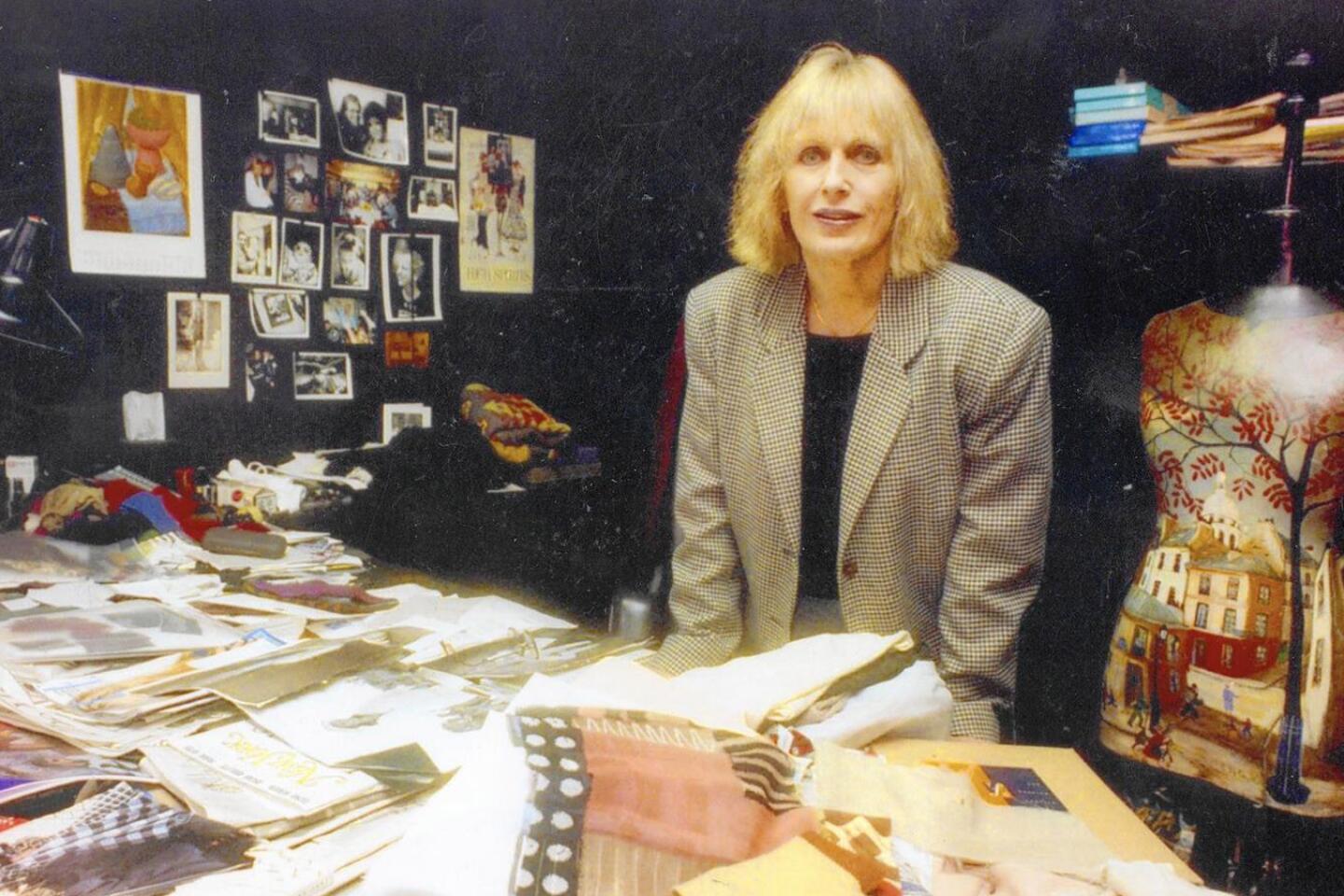

The designer was a force for working women who wanted a stylish but affordable look. Her eponymous brand became a favorite of career women. She was 80. Full obituary

(Adrienne Helitzer / Los Angeles Times) 14/64

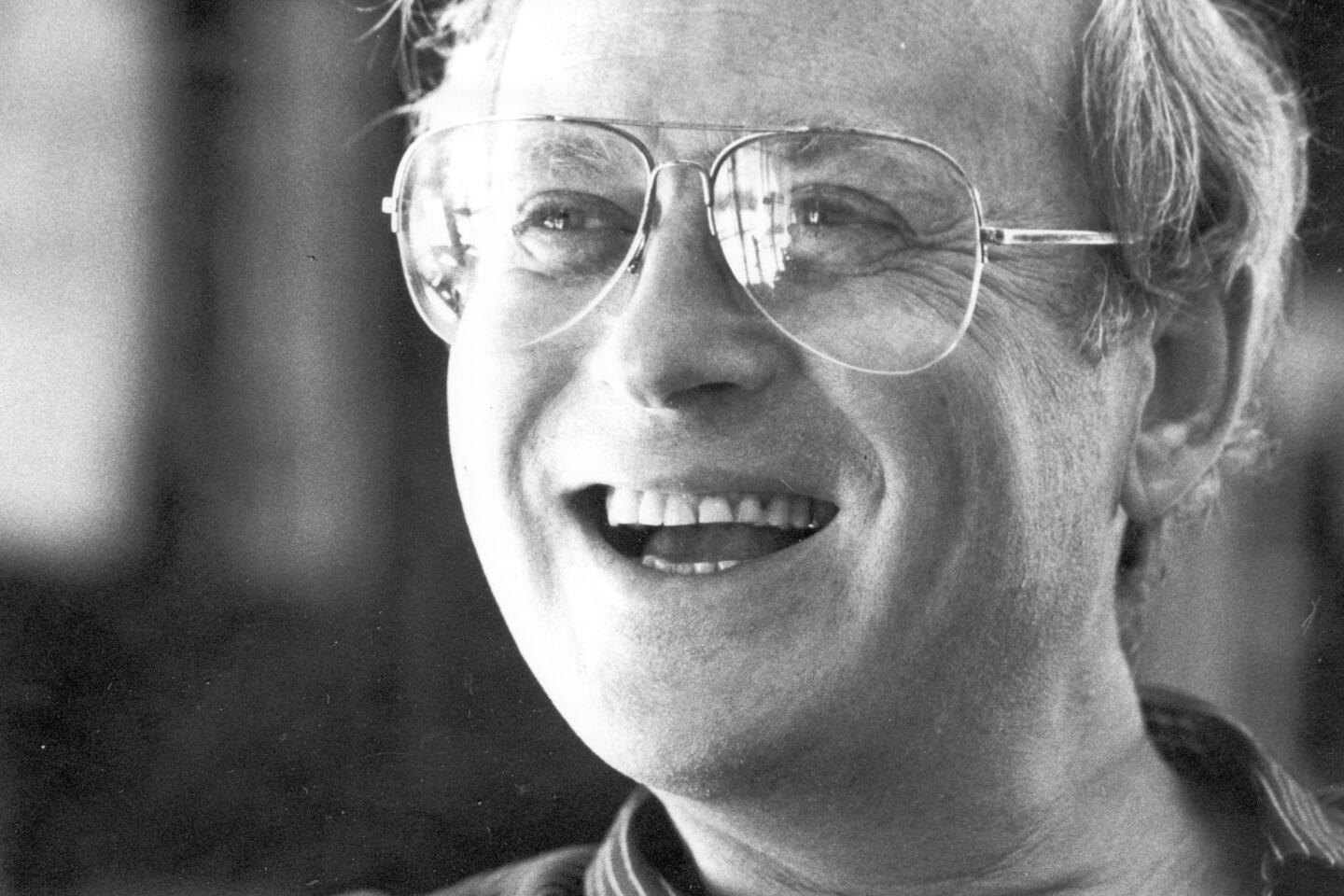

The publisher mined California’s counterculture for bestsellers, bringing out such consciousness-expanding works as “Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain” by Betty Edwards. He was 83. Full obituary

(Ken Hively / Los Angeles Times) 15/64

Considered one of the iconic figures of modern jazz, Woods was also thought of by some as the rightful heir to Charley “Bird” Parker. He may be best known to pop audiences for his alto saxophone work on Billy Joel’s “Just the Way You Are,” Steely Dan’s “Doctor Wu” and Paul Simon’s “Have a Good Time.” He was 83. Full obituary

(Hiroyuki Ito / Getty Images) 16/64

One of the best centers to ever play in the NBA, Malone was named to the NBA’s 50th anniversary all-time team and led the Philadelphia 76ers to the NBA championship in 1983, when he also won the most valuable player award, one of three in his 21-year career. The 14-time All-Star entered the Hall of Fame in 2001. He was 60. Full obituary

(Elise Amendola / Associated Press) 17/64

The Yankee Hall of Fame catcher was renowned as much for his dizzying malapropisms as his record 10 World Series championships. His wacky public utterances -- spoken with utter sincerity -- were quoted by presidents, professors and public speakers of all stripes, among millions of others. He was 90. Full obituary

(Ron Frehm / Associated Press) 18/64

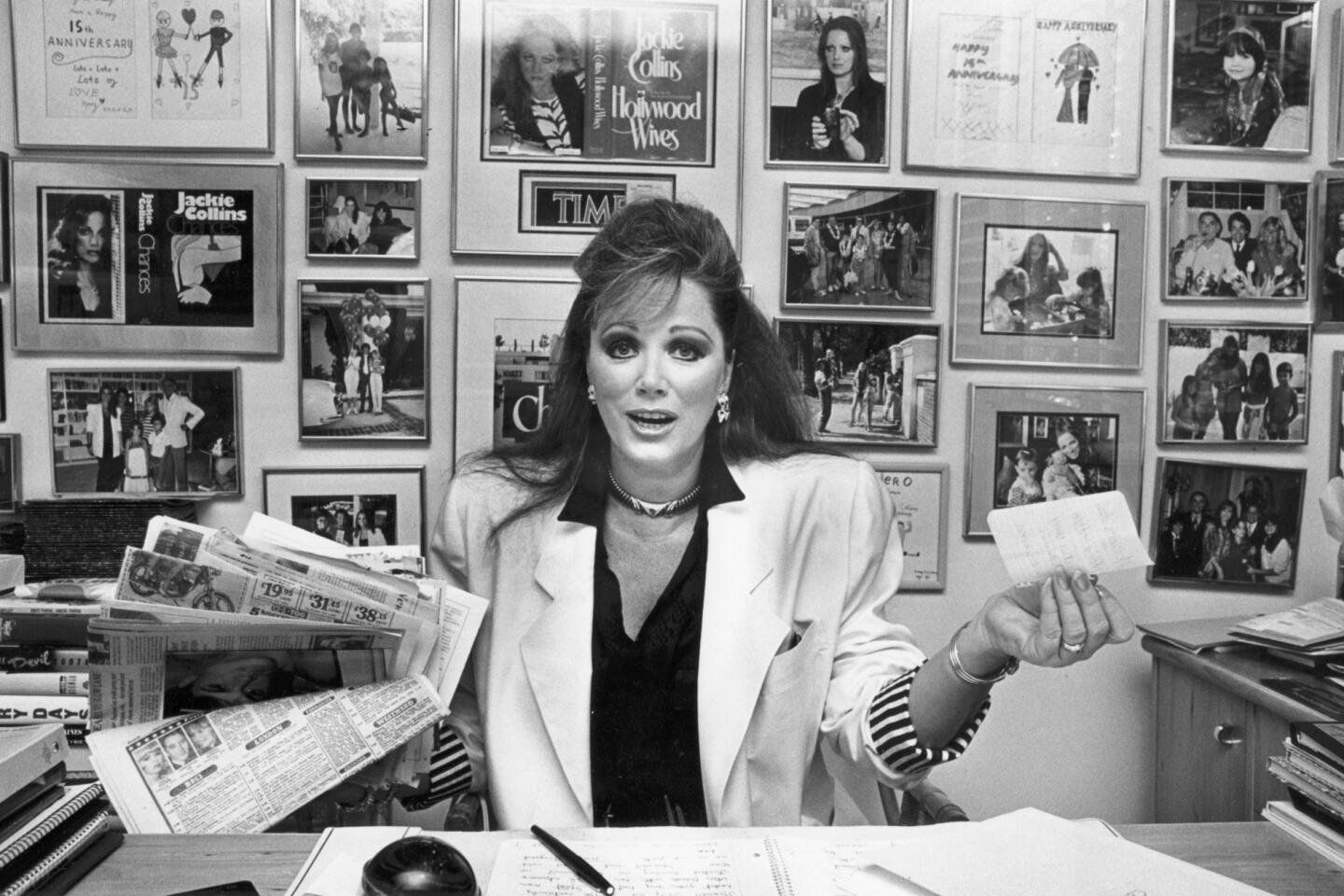

The best-selling author was a fixture on the Hollywood scene, where she frequented celebrity hangouts in search of story material. Her novels, including “Hollywood Wives,” “Hollywood Husbands” and “Hollywood Kids,” together sold more than 500 million copies around the world. She was 77. Full obituary

(Tony Barnard / Los Angeles Times) 19/64

The Japanese American tail gunner overcame the American military’s discriminatory policies to fly on 58 bombing missions over three continents during World War II, including raids on Tokyo in the final months of the war. He was 98. Full obituary

(Spencer Weiner / Los Angeles Times) 20/64

Best known for star turns in Disney comedies such as “The Love Bug,” “That Darn Cat!” and “The Ugly Dachshund,” Jones often played the somewhat bumbling good guy. Later, his religious conversion -- he became a born-again Christian -- altered not only the course of his life but his career choices. He was 84. Full obituary

(Dan Grossi / Associated Press) 21/64

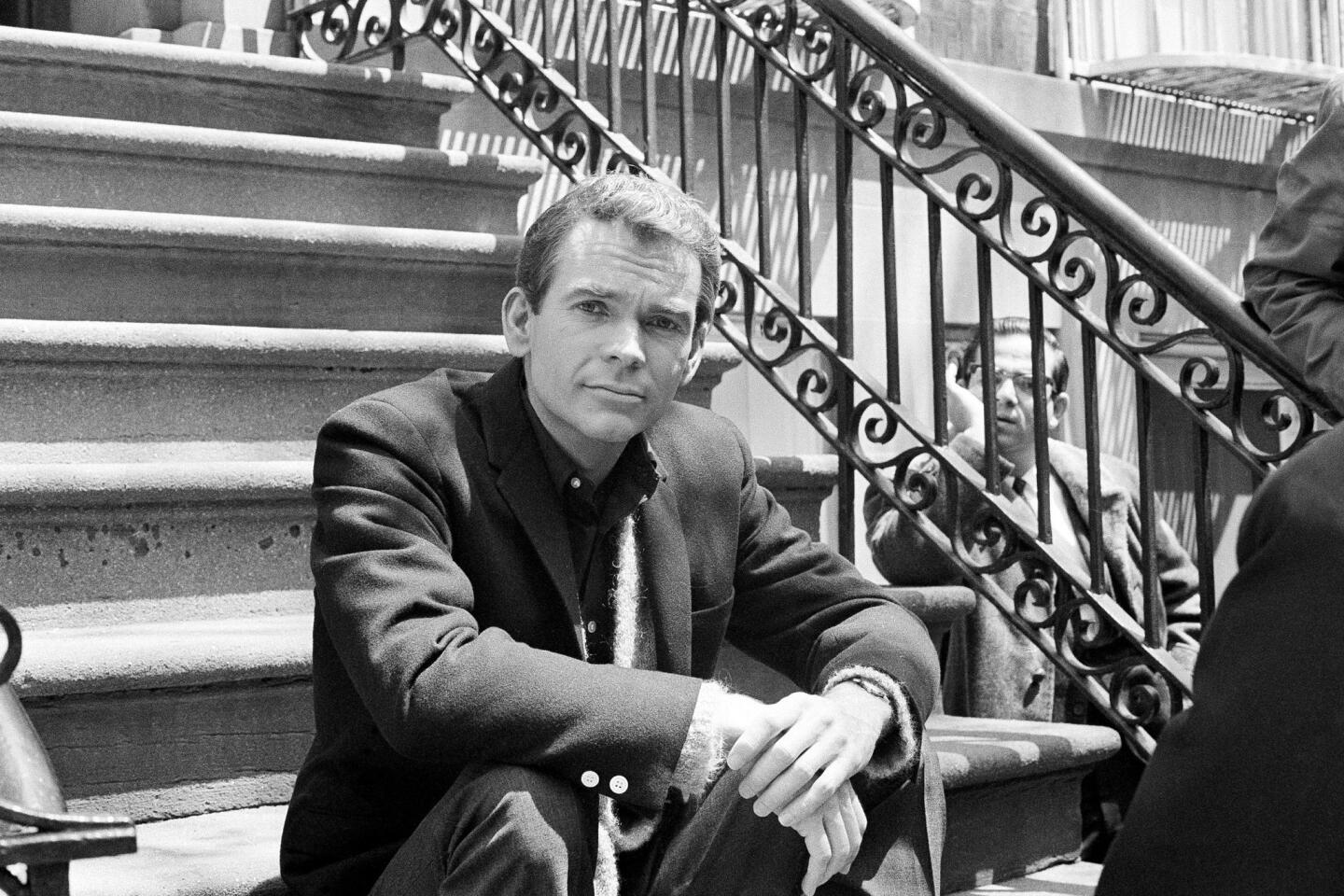

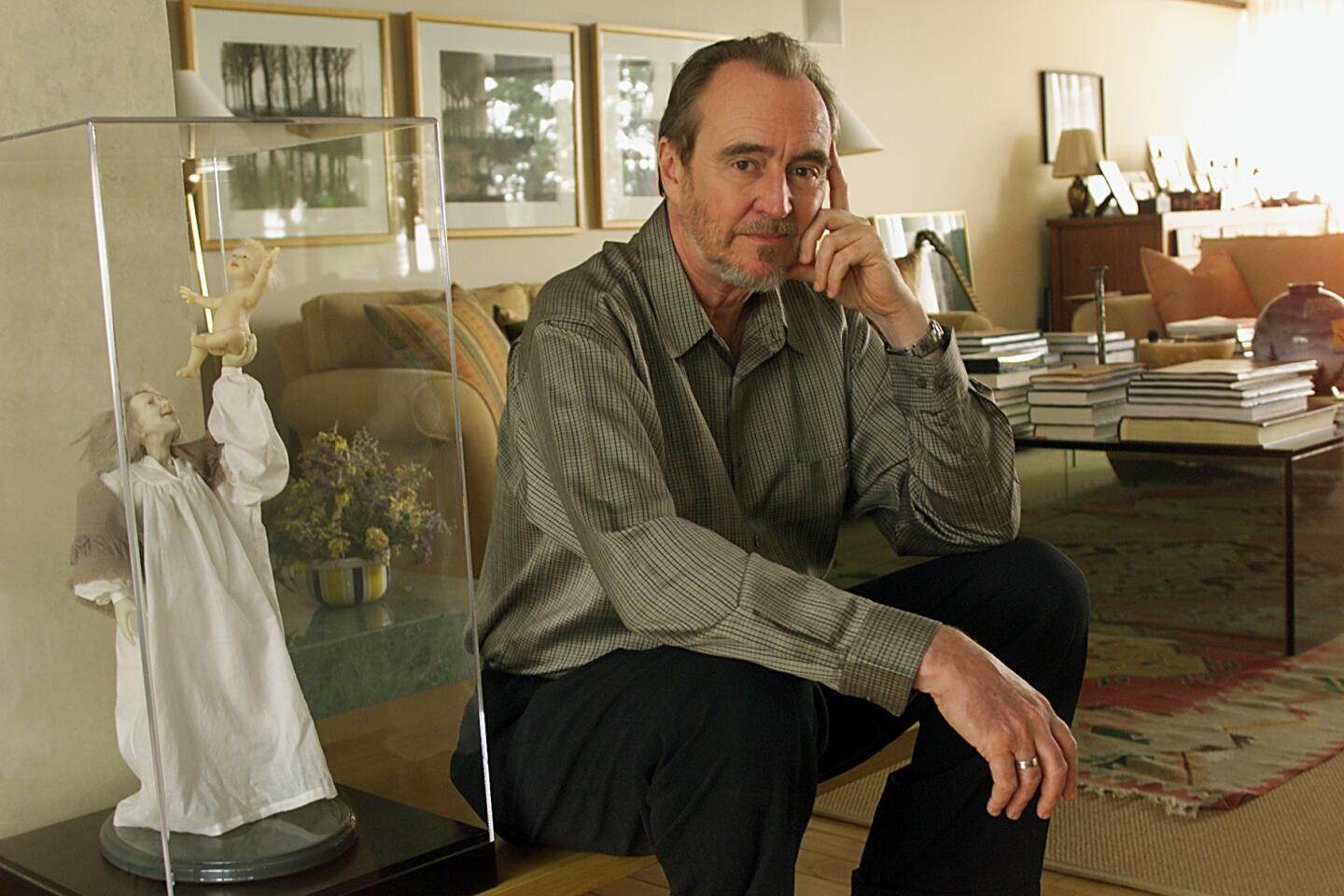

His name forever linked to horror films, Craven created some of the genre’s most influential films, including 1977’s “The Hills Have Eyes,” 1984’s “A Nightmare on Elm Street” and 1996’s “Scream.” He was 76. Full obituary

(Kirk McKoy / Los Angeles Times) 22/64

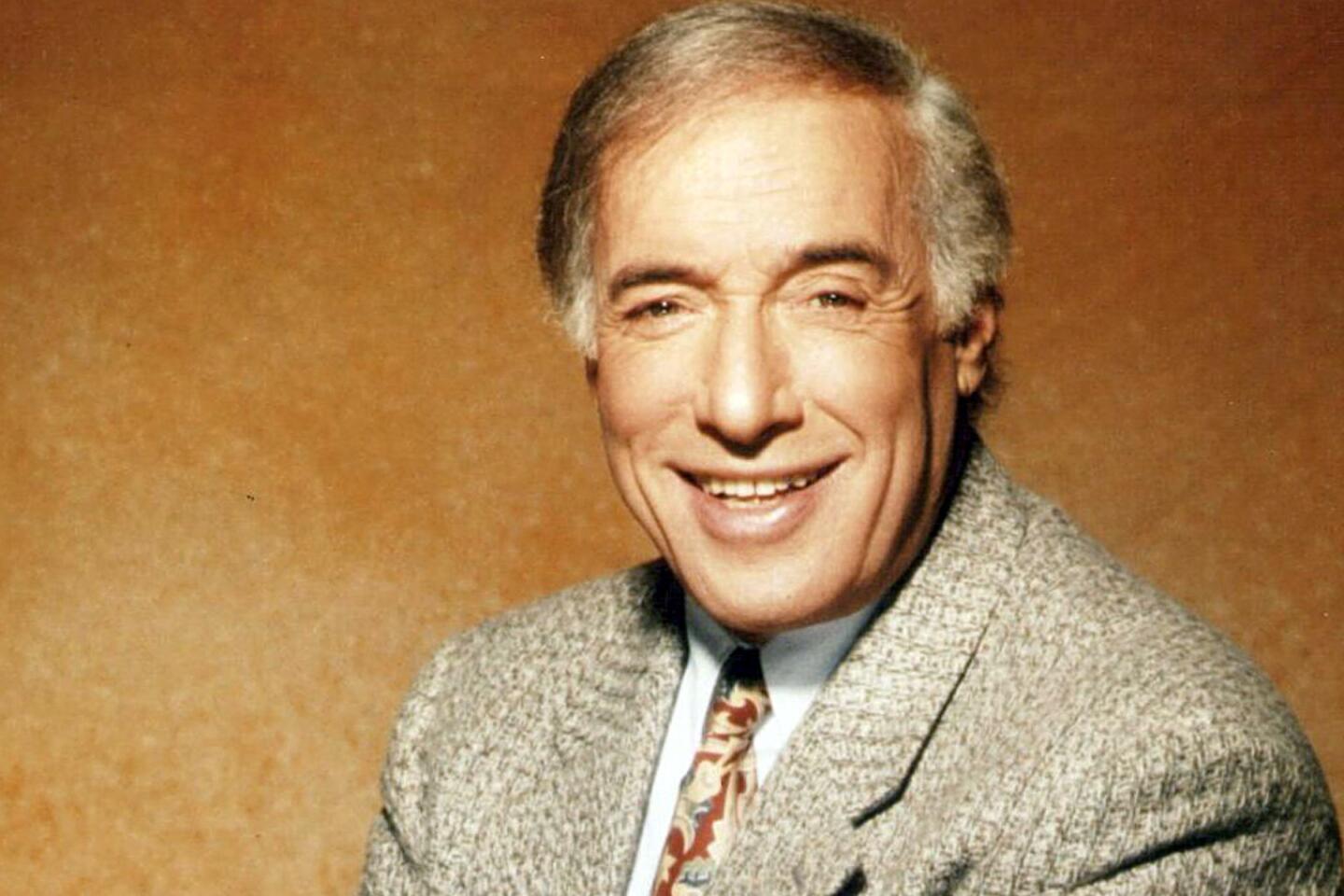

The veteran producer-director brought Hollywood headliners into America’s living rooms through live television in the 1950s. His creative partnership with Norman Lear produced such films as “Come Blow Your Horn,” “Divorce American Style” and groundbreaking television sitcoms such as “All in the Family,” “Maude” and “Sanford and Son.” He was 89. Full obituary

(Harry Langdon / Associated Press) 23/64

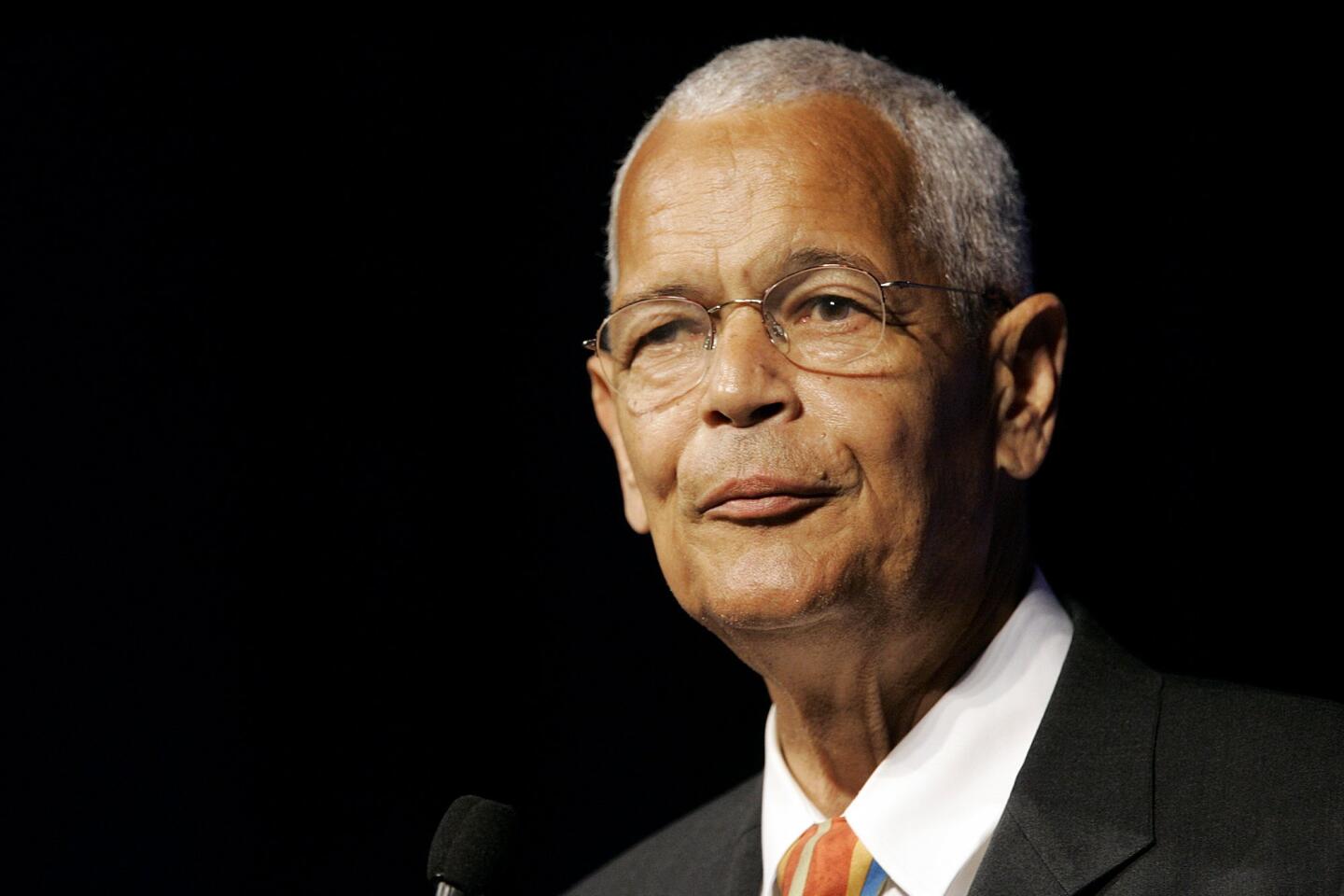

Charismatic and eloquent, the civil rights leader had numerous key accomplishments, including co-founding the landmark Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and serving as board chairman of the NAACP. He was 75. Full obituary

(Paul Sancya / Associated Press) 24/64

After being shot in the face during a bar fight at 23 and losing his sight, Manning went on to become a poet, athlete and founder of a theater company in Watts. He was 60. Full obituary

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times) 25/64

The British pop singer had a string of hits starting in 1964 with “Anyone Who Had a Heart,” written by Burt Bacharach and Hal David, and “You’re My World.” Starting in the 1980s, she became an enormously popular personality on British TV. She was 72. Full obituary

(William Vanderson / Getty Images) 26/64

The Egyptian-born actor, right, rose to international acclaim after starring with Peter O’Toole in “Lawrence of Arabia.” He went on to make some 90 movies in his career, including “Doctor Zhivago” and “Funny Girl.” He was 83. Full obituary

(Columbia TriStar / Getty Images) 27/64

In a career that spanned half a century, Weintraub proved a force in the worlds of music, film and television. He had an eye for talent, discovering a little-known singer-songwriter named John Denver, for example, and launching him to international stardom. Weintraub was 77. Full obituary

(Lawrence K. Ho / Los Angeles Times) 28/64

A stage and screen actor, Van Patten was most famous for starring as loving father Tom Bradford in the television series “Eight Is Enough.” His roles in movies included “Soylent Green,” “High Anxiety” and “Spaceballs.” He was 86. Full obituary

(Boris Yaro / Los Angeles Times) 29/64

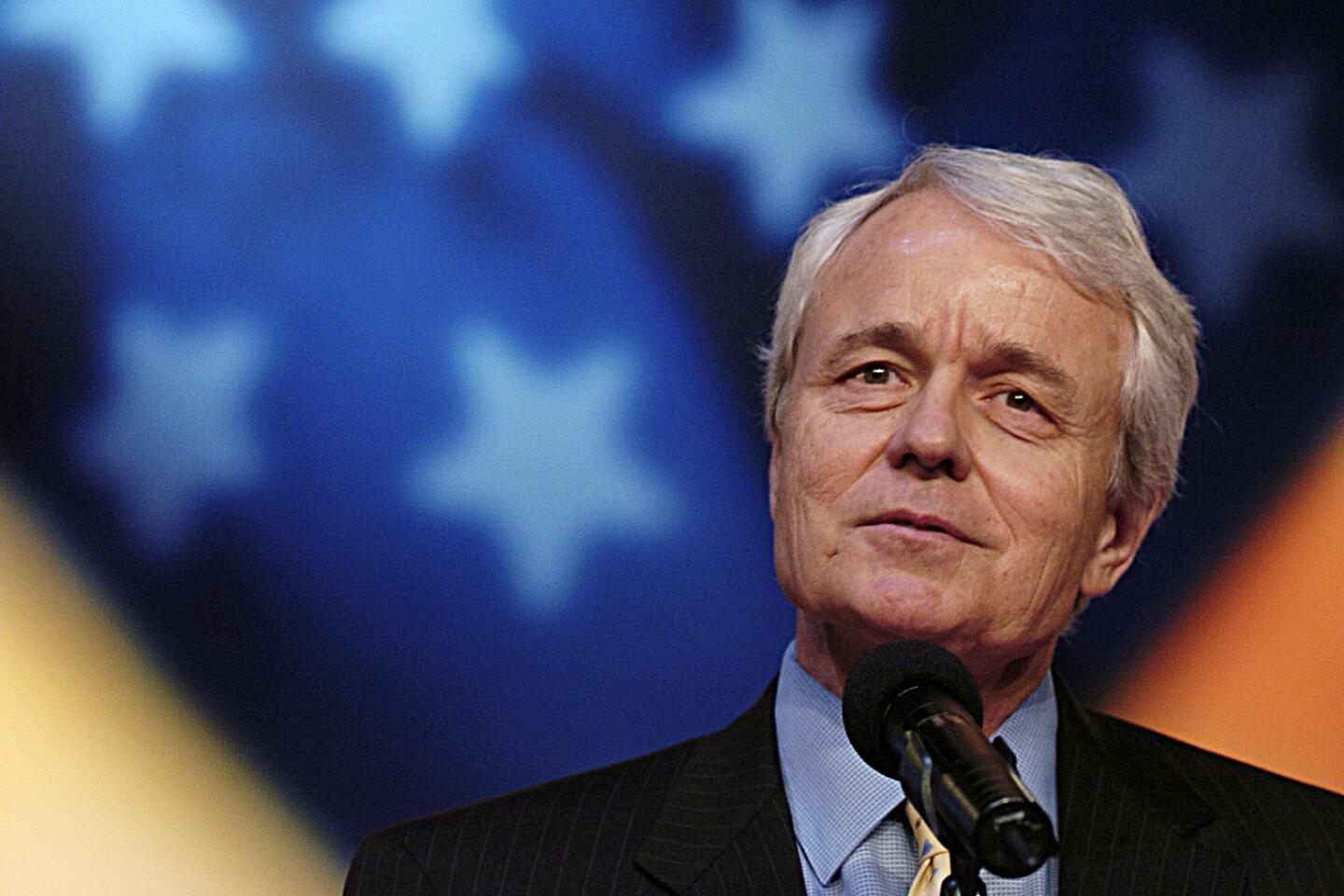

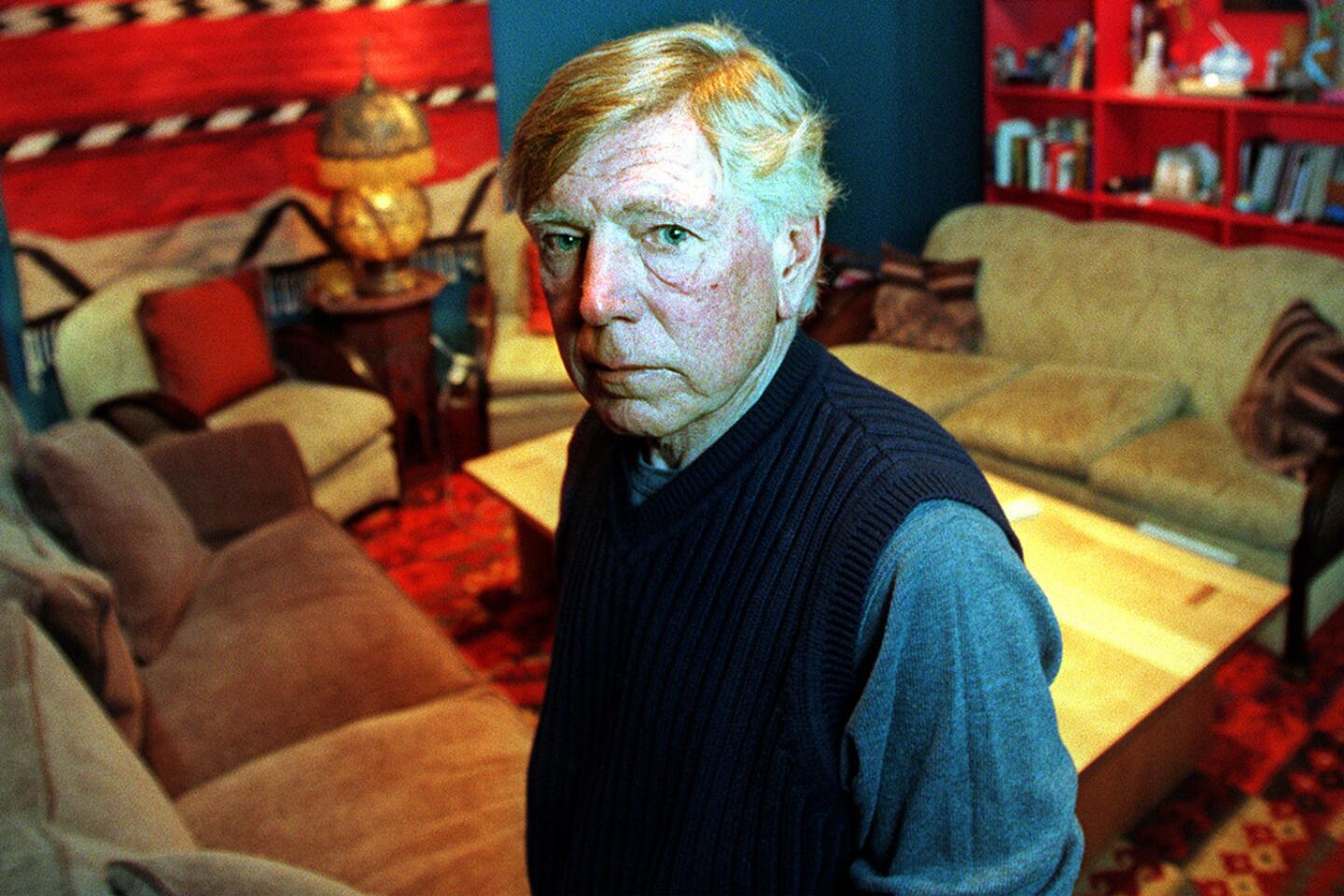

A courageous editor, Carroll guided the Los Angeles Times to new heights, including a record 13 Pulitzer Prizes in five years. Of the 13 Pulitzers the paper won under Carroll, five were awarded in 2004. It was the largest number The Times ever won in a single year and the second-largest in the history of the prizes. He was 73. Full obituary

(Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times) 30/64

One of the first superstar chefs, Vergé, pictured here with actor John Travolta, was known for light, fresh and artfully plated food. He turned his restaurant, Le Moulin de Mougins in France, into a landmark of French gastronomy and a beacon of nouvelle cuisine. He was 85. Full obituary

(Gilberte Tourte / Associated Press) 31/64

Ronnie Gilbert , pictured second to the right, was a member of the folk group the Weavers, who, at their peak, were known for spirited renditions of famous folk songs -- as well as antiwar protest songs that would lead to their temporary disbandment during the Red Scare. The group made a successful comeback three years later, going on to inspire other folk performers like the Kingston Trio. She was 88. Full obituary

(RICHARD DREW / AP) 32/64

Prior to his surrender to U.S. forces in 2003, Tarik Aziz was known as the diplomatic symbol of the Iraqi government, the man Saddam Hussein deployed to convey his message to the world. He had been in custody since his surrender. He was 79. Full obituary

(Peter Dejong / Associated Press) 33/64

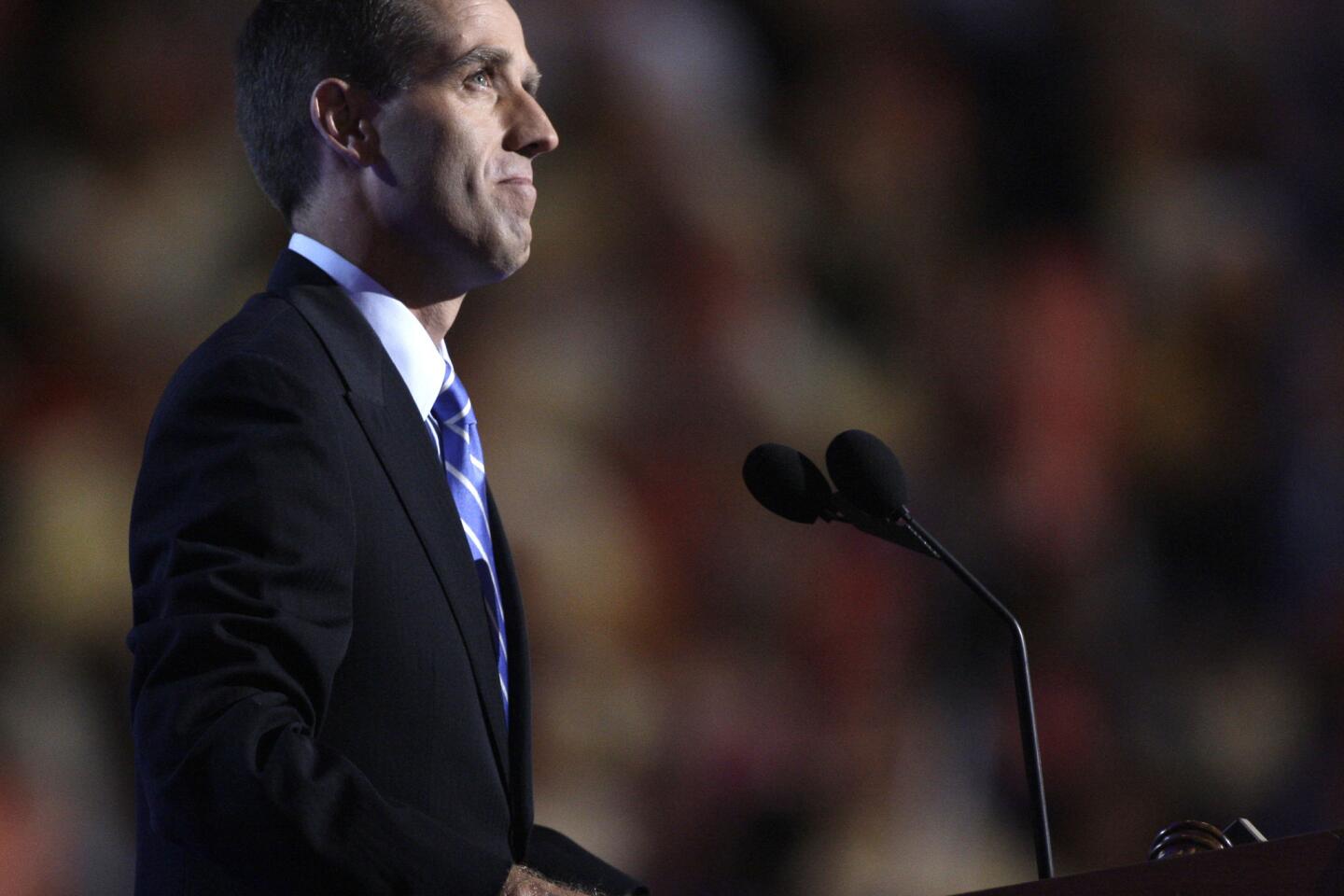

Son of Vice President Joe Biden, Beau Biden was the former attorney general for the state of Delaware and a U.S. Army captain. A promising young figure in Democratic Party politics, Beau was considered a leading contender in next year’s governor’s election in Delaware. He was 46. Full obituary

(Paul Sancya / AP) 34/64

The Nobel Prize winner transformed economics and was known as one of the greatest mathematicians of his time. The inspiration for Ron Howard’s 2001 Oscar-winning film “A Beautiful Mind,” he eventually recovered from his devastating illness, defying a common misconception about schizophrenia. He was 86. Full obituary

(AFP / Getty Images) 35/64

The former jazz musician became a deeply influential and highly visible executive at Columbia Records, Blue Note Records and other major labels. He moved from one lofty record company job to another, leaving his mark along the way. He was 79. Full obituary

(Seth Wenig / Associated Press) 36/64

The blues legend took the musical genre from the barrooms and back porches of the Mississippi Delta to Carnegie Hall and the world’s toniest concert stages. The 15-time Grammy winner created a unique style that made him one of the most respected and influential blues musicians ever. He was 89. Full obituary

(Ken Hively / Los Angeles Times) 37/64

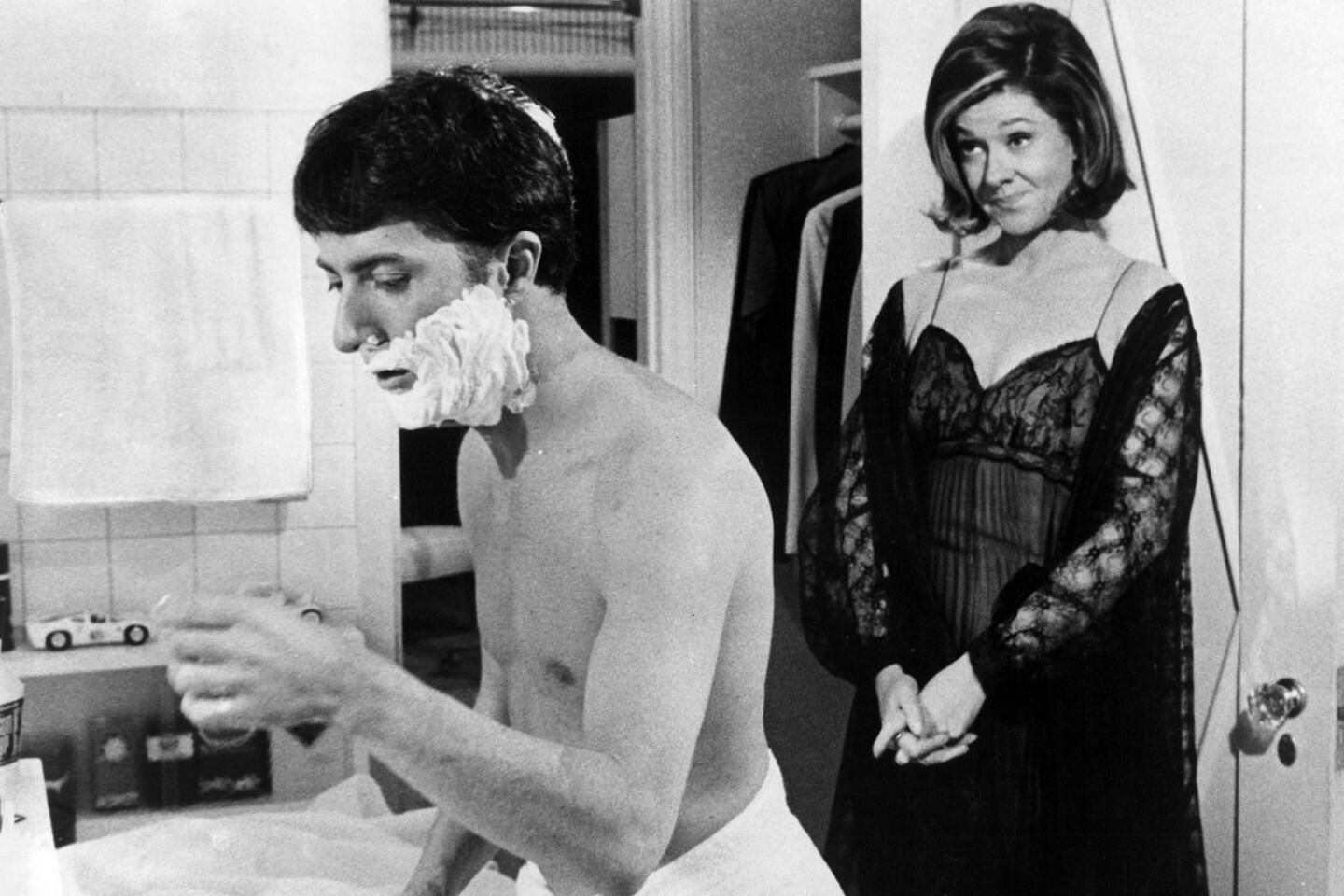

Best known for her role as the clueless mother of a confused, young Benjamin Braddock (Dustin Hoffman) in “The Graduate,” Wilson also acted in more than 30 movies and numerous Broadway plays. She was 94. Full obituary

(Archive Photos / Getty Images) 38/64

The ex-wife of Johnny Carson, Joanne Carson was married to “The Tonight Show” host from 1963 to 1972. She later in life became a confidant of Truman Capote. She was 83. Full obituary

(Hulton Archive / Getty Images) 39/64

The conceptual artist left a long-lasting legacy with “Urban Light,” the ranks of vintage lampposts tightly arrayed outside the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Installed in 2008, it rapidly became something of an L.A. symbol. Burden was 69. Full obituary

(Mel Melcon / Los Angeles Times) 40/64

Blake won a 1991 screenwriting Oscar for Kevin Costner‘s film “Dances With Wolves,” which became the first western to win a best picture Academy Award since “Cimarron” in 1931. He was 69. Full obituary

(Reed Saxon / Associated Press) 41/64

A celebrated Russian ballerina famous for her swan-like arms, powerful leaps and rebel spirit on and off the stage, Plisetskaya was renowned for passionate performances that contrasted with the ethereal style of many other dancers. She was 89. Full obituary

(AFP / Getty Images) 42/64

Meadows was known for her work on the game show “I’ve Got a Secret.” The show also introduced her to the man who became her second husband, Steve Allen, above with Meadows in 1979, who was the first host of NBC’s “Tonight Show.” Until his death in 2000, they were one of the most recognizable performing couples in Hollywood. She was 95. Full obituary

(Martha Hartnett / Los Angeles Times) 43/64

King, a singer-songwriter, had one of the most enduring hits ever with “Stand By Me.” He was also known for his solo hits “Spanish Harlem” and “I (Who Have Nothing),” and “There Goes My Baby” and “Save the Last Dance for Me” with the Drifters. He was 76. Full obituary

(AFP / Getty Images) 44/64

The influential master of the lampoon channeled his off-the-wall sensibility into groundbreaking radio shows, comedy albums and hundreds of humorous television commercials for products such as chow mein and prunes. He was 88. Full obituary

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 45/64

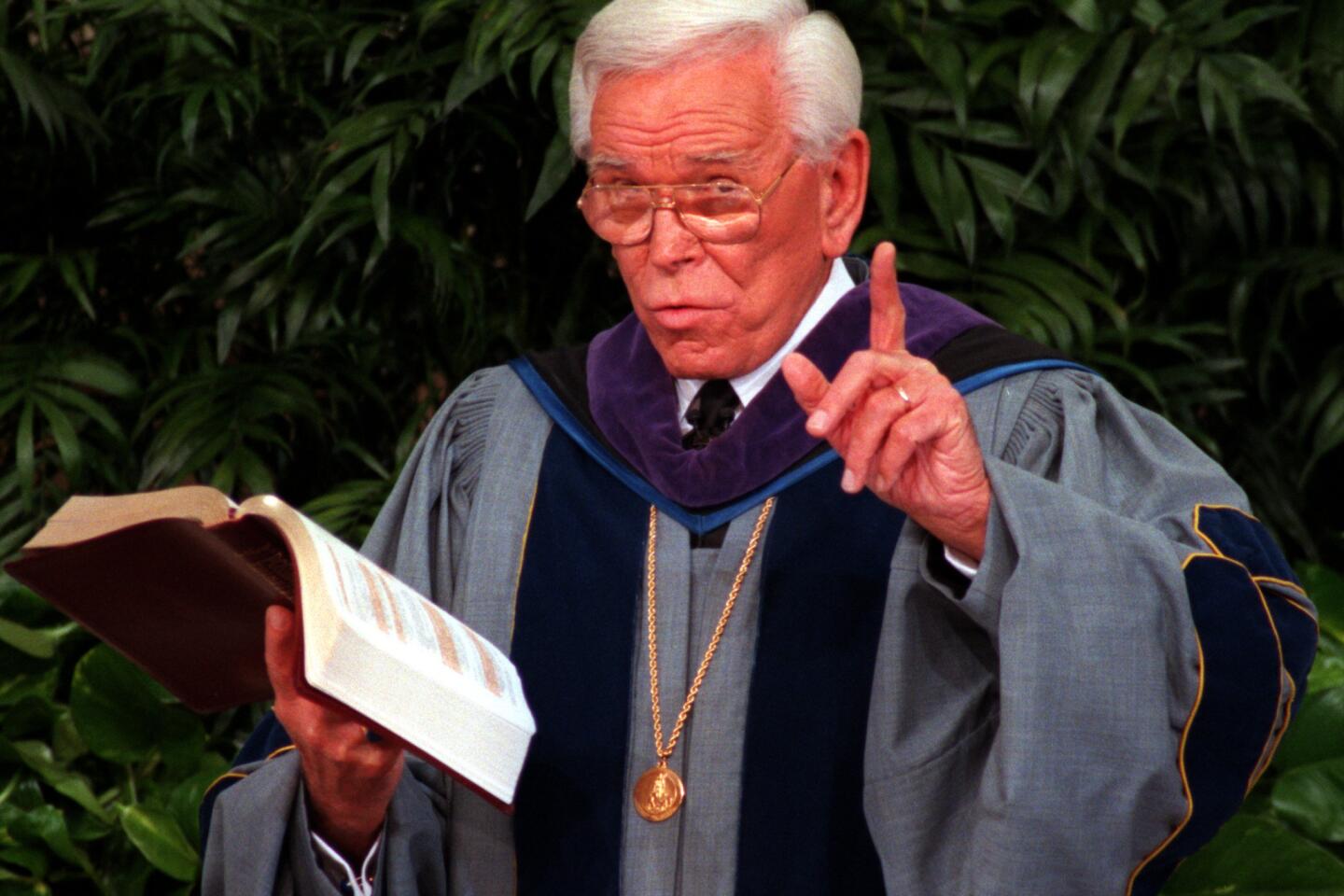

He built the Crystal Cathedral in Garden Grove as the embodiment of an upbeat, modern vision of Christianity, only to see his ministry shattered by family discord and financial ruin. He was 88. Full obituary

(Al Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 46/64

The science teacher turned weatherman who joined KABC-TV in 1972 and spent nearly two decades exuberantly delivering the local forecast was 92. Full obituary.

(Anne Cusack / Los Angeles Times) 47/64

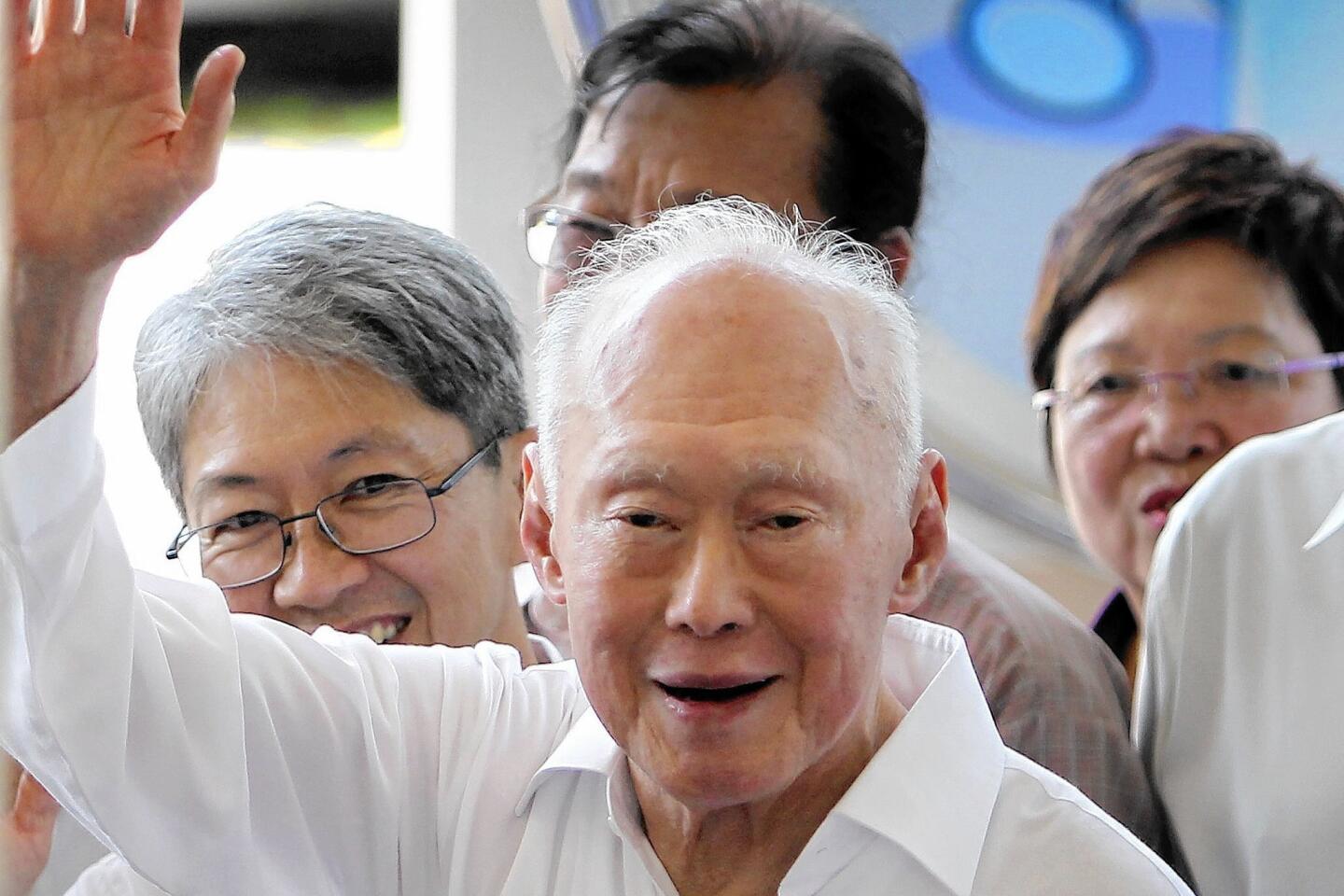

While presiding over a government that squelched dissent and characterizing opponents as “mediocrities and opportunists,” he transformed the backwater city-state of Singapore into one of the world’s most efficient and prosperous international business centers. Full obituary.

(Wong Maye-E / Associated Press) 48/64

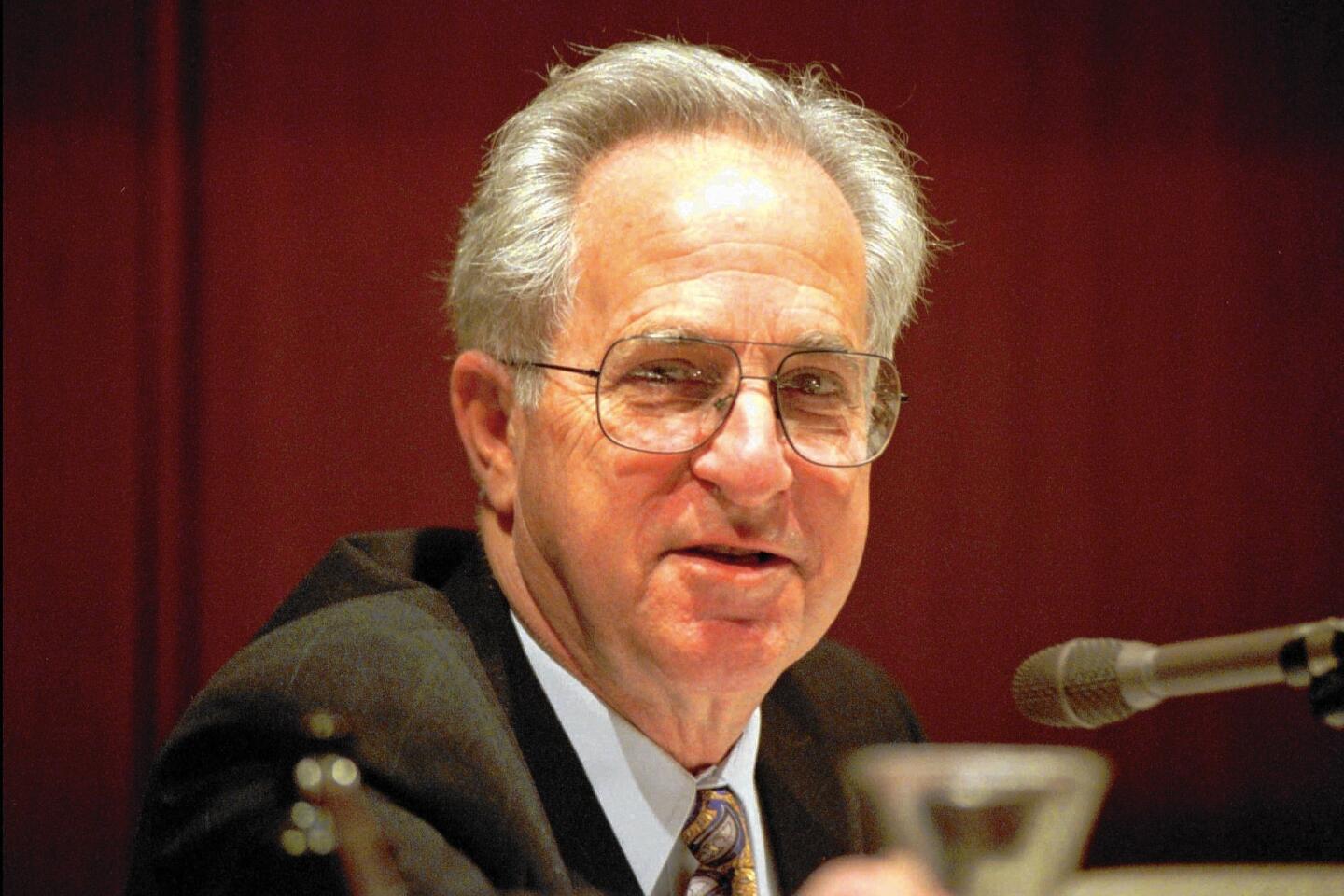

The constitutional scholar with a modest manner and a homespun sense of humor was a former chancellor of UC Irvine and president of the UC system for three years in the 1990s. He was 91. Full obituary.

(Dwayne Newton / Associated Press) 49/64

The pioneering figure in postmodern design in the 1980s and ‘90s added historical ornament and bright color to prominent and often controversial buildings. As a product designer, he brought high-design housewares to a broad public. He was 80.

Full obituary (Chris Felver / Getty Images) 50/64

As the University of Notre Dame’s president for 35 years, he helped build the university into an academic powerhouse. He was once featured on the cover of Time magazine, which described him as the most influential figure in the reshaping of Catholic education. He was 97.

Full obituary (Joe Raymond / Associated Press) 51/64

A versatile jazz trumpeter and flugelhorn player, Terry played with musical greats including Count Basie, Duke Ellington and Billie Holiday. As part of the NBC “Tonight Show” Orchestra, he was the network’s first African American staff musician. He was 94.

Full obituary (AFP / Getty Images) 52/64

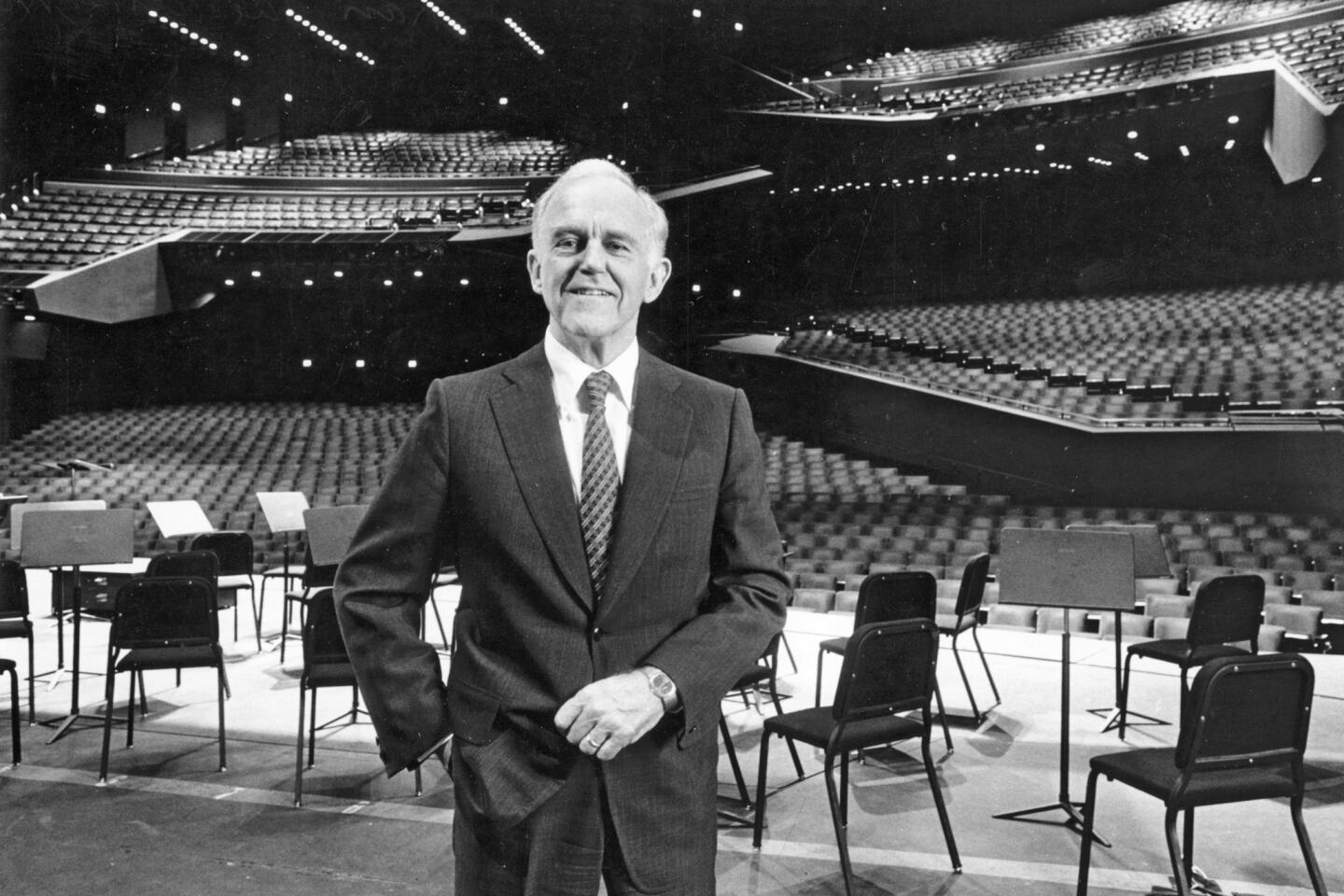

The courtly real estate developer and arts philanthropist was instrumental in transforming Orange County from a provincial bedroom community into a nexus of culture and commerce. He was 91.

Full obituary (Don Kelsen / Los Angeles Times) 53/64

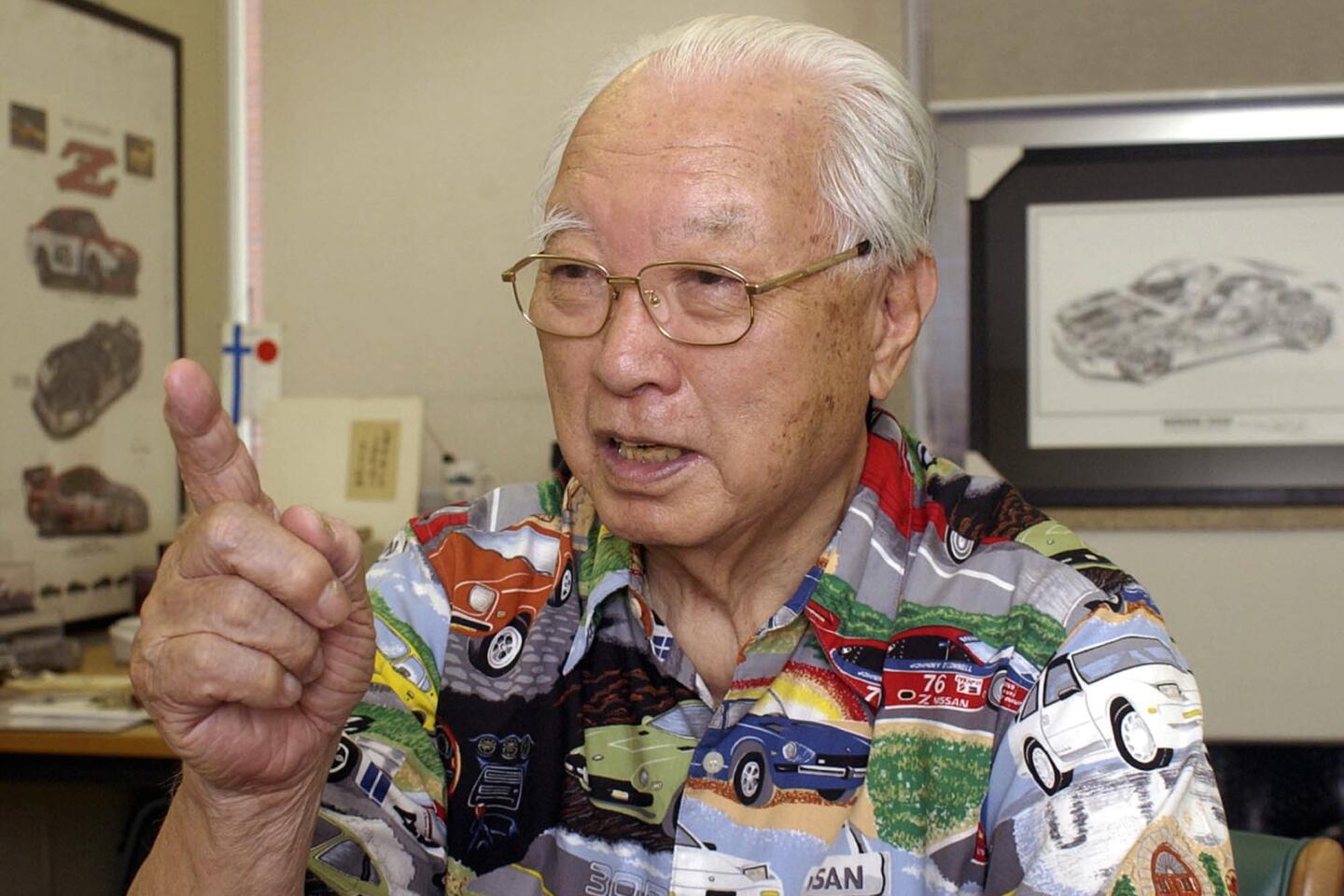

The auto marketing guru spearheaded Nissan’s launch into the U.S. car market. He’s credited as the executive who helped Japanese autos gain acceptance in the U.S. He was 105.

Full obituary (Tsugufumi Matsumoto / Associated Press) 54/64

The Pulitzer Prize-winning poet and former U.S. poet laureate wrote elegies to American blue-collar workers sweating through despair-laced jobs. He wanted to “find a voice for the voiceless,” he told Detroit magazine. He was 87.

Full obituary (Gary Kazanjian / Associated Press) 55/64

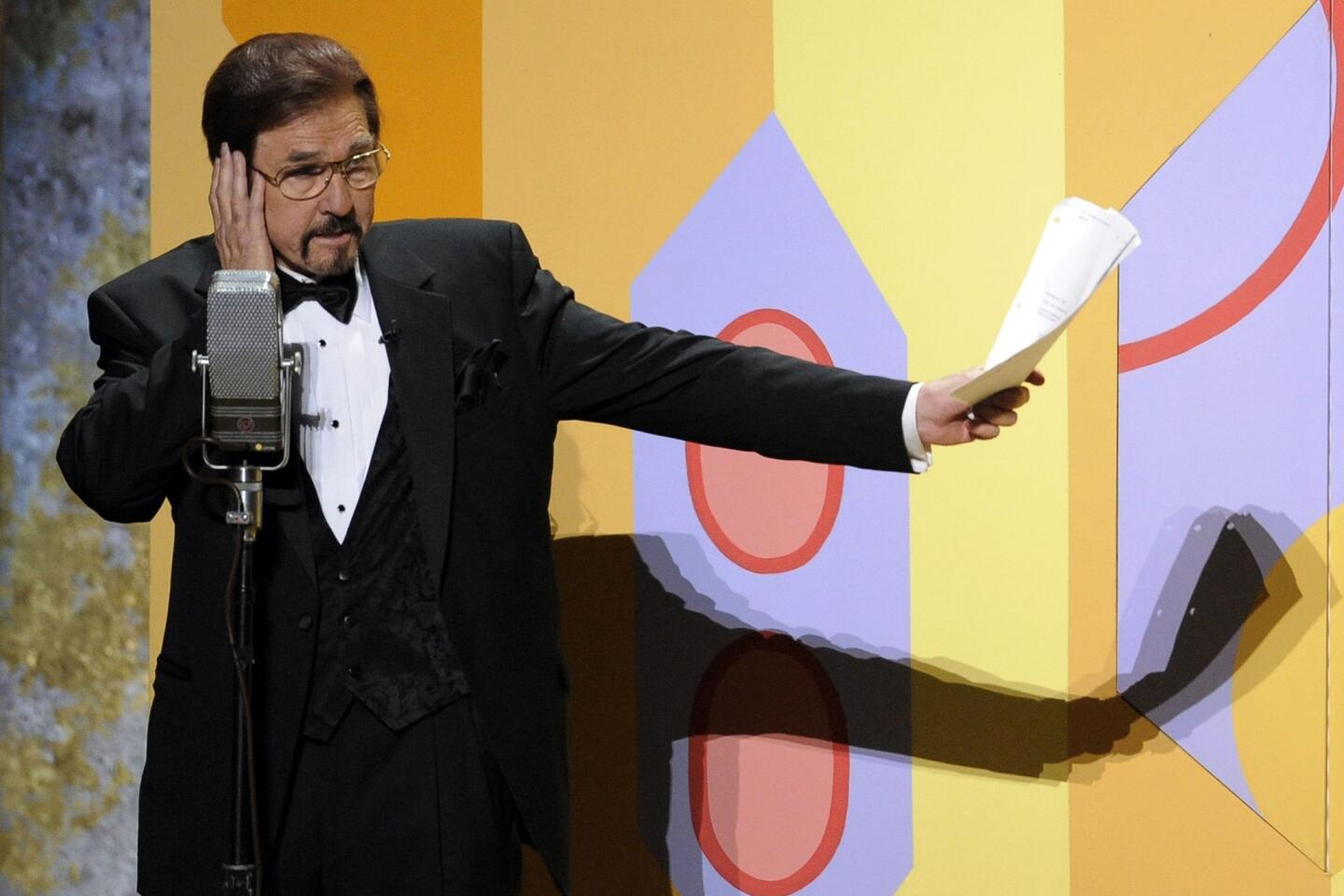

The radio broadcaster vaulted to fame playing the zany announcer in the landmark TV comedy series “Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-In.” He was 80.

Full obituary (Mark J. Terrill / Associated Press) 56/64

An accomplished architect, Jerde created “experience” malls and related projects -- including Universal CityWalk and Horton Plaza in San Diego. He also helped oversee the design of the 1984 Los Angeles Olympic Games. He was 75.

Full obituary (Lawrence K. Ho / Los Angeles Times) 57/64

Known as the “Jackie Robinson of golf,” Sifford was the first black player to earn a Professional Golfers Assn. of America membership card. His success helped clear the way for generations of minority players. He was 92.

Full obituary (Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 58/64

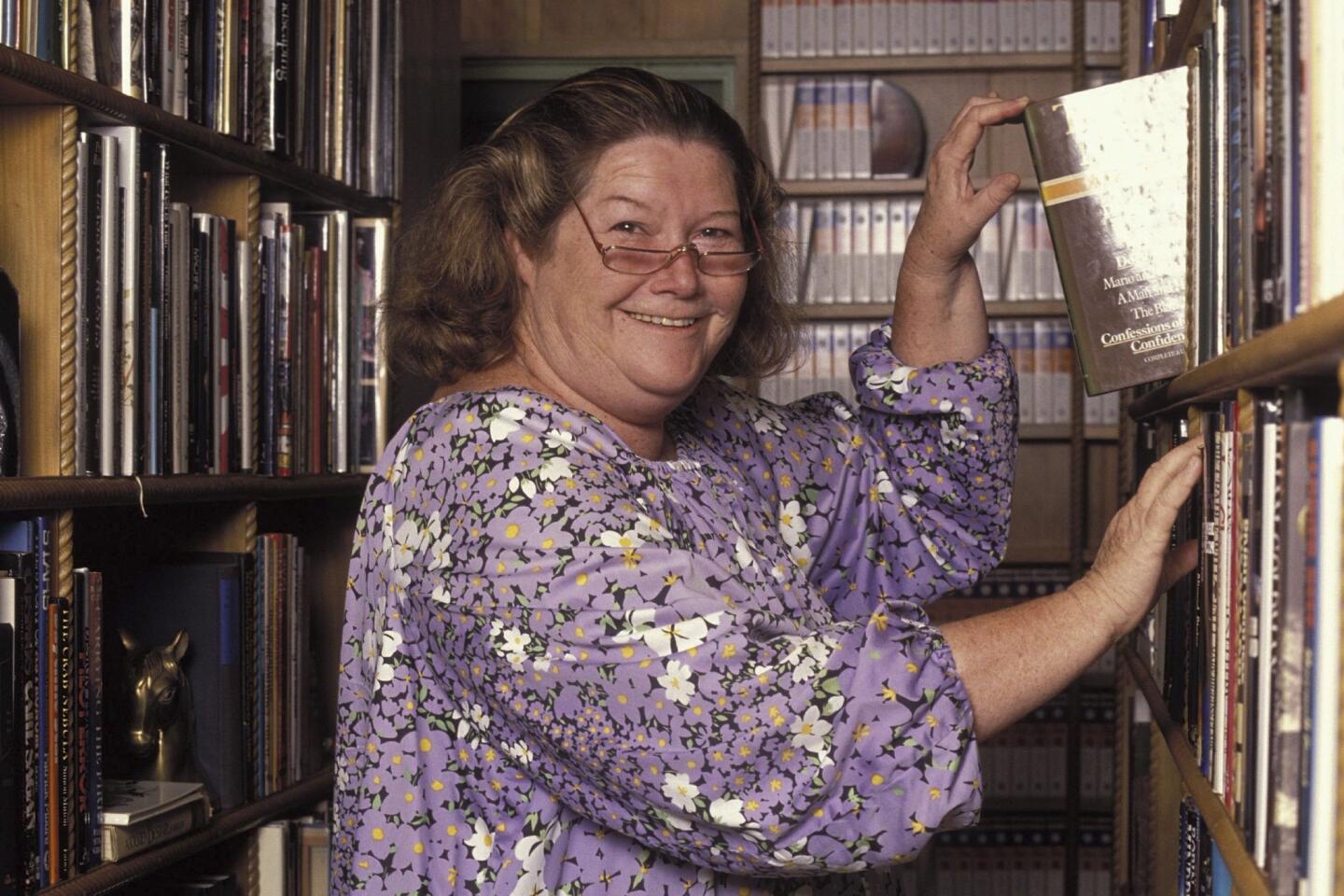

The Australian author wrote “The Thorn Birds,” her 1977 saga of a baronial outback family and a priest tormented by love. It sold millions of copies and was made into TV’s second-most-popular miniseries, topped only by “Roots.” She was 77.

Full obituary (Patrick Riviere / Getty Images) 59/64

Abdullah guided the Saudi kingdom through the challenges posed by the Sept. 11 attacks in the United States, the war in neighboring Iraq, the disintegration of Syria, the upheavals of the “Arab Spring” and the rise of Islamic State. He was 90.

Full obituary (Brendan Smialowski / Associated Press) 60/64

The three-term governor of New York was a fierce champion of liberal causes. A fiery orator, he became one of the Democratic Party’s most forceful voices on the need to address economic inequality. He was 82.

Full obituary (Al Seib / Los Angeles Times) 61/64

The son of one of the movie business’ original moguls, the younger Goldwyn started his own independent film company, which became a major force in 1980s and ‘90s Hollywood. He was 88.

Full obituary (Ellis R. Bosworth / Associated Press) 62/64

The Grammy-winning singer and composer was known for pioneering a gospel sound with a contemporary feel. He influenced artists including Michael Jackson, Elvis Presley and Paul Simon. He also led services at the church his father founded in the San Fernando Valley. He was 72.

Full obituary (Brian Vander Brug / For the Times) 63/64

A leading advocate for peace between Islam and other religions, Hathout for roughly three decades led the Islamic Center of Southern California in Los Angeles, one of the nation’s most influential mosques. He was 79.

Full obituary (Al Seib / Los Angeles Times) 64/64

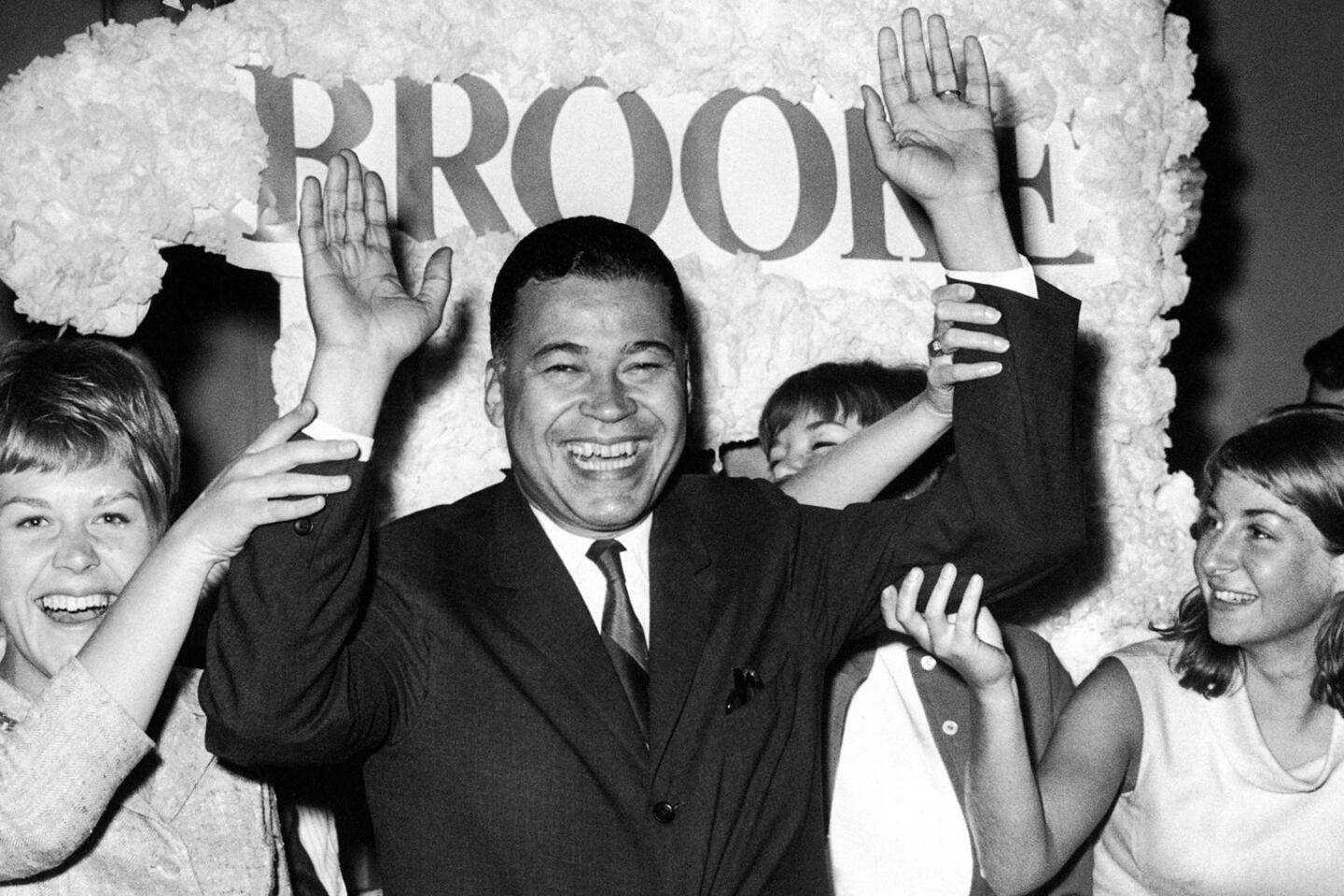

The first African American elected to the U.S. Senate by popular vote, he was also the first Republican senator to call for President Nixon’s resignation over the Watergate scandal. He achieved a number of social firsts in the Senate, including the integration of its barbershop. He was 95.

Full obituary (Frank C. Curtin / Associated Press) When the family was together again, they moved to New York. Vera’s mother held a variety of jobs to support them. When she bought the chair, she was working as a children’s matron in a movie theater.

Both of Williams’ parents were immersed in radical politics. Her father carried her on his shoulders to May Day parades and told her stories about the deadly Triangle Shirtwaist fire that sparked workplace reforms. Her mother agitated for day care, free dentists and summer camps for poor children.

She also ensured that her daughters were exposed to art and culture, finding free programs where they could paint, sculpt, dance and act.

“And that was a blessing, for I was a child with a lot to say,” Williams wrote in an autobiographical essay for “Children’s Books and Their Creators.” “When people grew tired of my talking, I drew pictures. But then I had to tell about the pictures.”

When she was 9, one of her paintings was displayed in the Works Progress Administration exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. She went on to attend the experimental Black Mountain College in North Carolina, where the faculty included composer John Cage, artist Josef Albers and choreographer Merce Cunningham. She earned a bachelor’s degree in graphic arts in 1949 and married a classmate, Paul Williams.

Their marriage ended in divorce in 1970. Williams is survived by their three children, Sarah, Jennifer and Merce, who was named after Cunningham; her sister, Naomi Rosenblum; and five grandchildren.

After college, Williams helped found an experimental school and artists’ community in Stony Point, N.Y. She also illustrated covers for a left-wing magazine.

Following her divorce, she moved to Vancouver, British Columbia, in Canada, where she lived on a houseboat and began to work on children’s books. The first book she illustrated was “Hooray for Me!” (1975), written by her friend Remy Charlip with Lilian Moore. She was both author and illustrator of her next book, “It’s a Gingerbread House,” published in 1978 when she was 51.

Three of her books feature a girl named Rosa and her tight-knit relationships with her mother and grandmother. The first in the series was “A Chair for My Mother,” about saving spare change in a jar to buy “a wonderful, beautiful, fat, soft armchair” after a fire destroyed the home Rosa shared with her family. A Kirkus review said it was “rare to find so much vitality, spontaneity, and depth of feeling in such a simple, young book.”

Williams’ mother, whose sacrifices inspired the book, died before it was published.

“When I got the inspiration for the book,” Williams said in an interview with Marguerite Feitlowitz, “I had the wonderful feeling that I now had the power, as a writer and an illustrator, to change the past into something happier than it really was, and to offer it as a gift to my mother’s memory.”

In “Something Special for Me” (1983), Williams portrays Rosa as torn between buying herself a birthday present or spending her family’s hard-earned money on something they can all enjoy. In “Music, Music for Everyone” (1984), the last book in the Rosa trio, the girl raises money and community spirit to help her grandmother.

Williams’ other books include “Three Days on a River in a Red Canoe” (1981), “Cherries and Cherry Pits” (1986) and “Scooter” (1993). Her last book, “Home at Last,” will be published next year.

As an activist, Williams campaigned for women’s rights, nonviolence and the environment. She occasionally served time for her beliefs, including a 1981 arrest during a women’s blockade of the Pentagon that led to a month in a federal prison camp in Alderson, W.Va.

“I don’t make a point of ending up in jail,” she told Feitlowitz. “But if you try to put your hopes and beliefs for a better life into effect, arrest is sometimes a hazard.

“I have to be able to say I did something to try to save our planet from destruction. It is my faith that we will.”

Twitter: @ewooLATimes