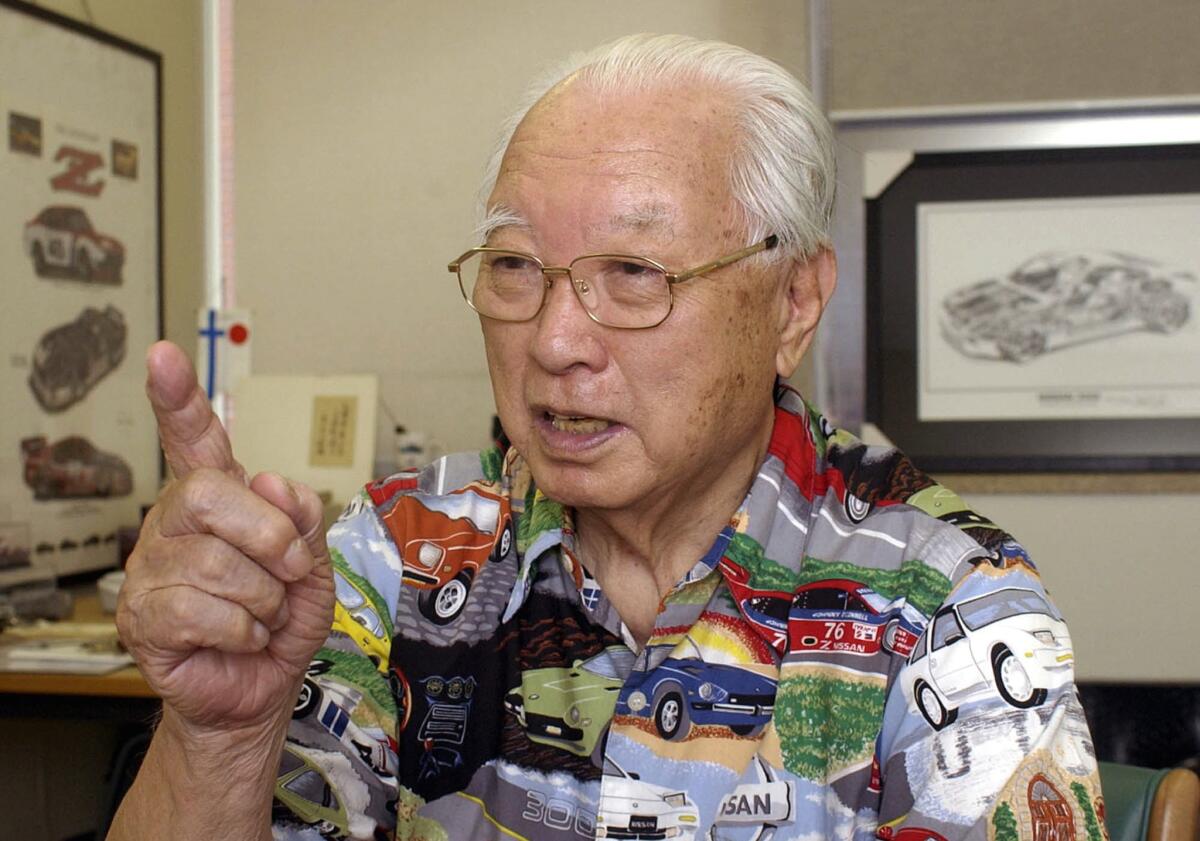

Yutaka Katayama dies at 105; auto exec led Japan’s rise in U.S. market

Yutaka Katayama, the auto marketing guru who spearheaded Nissan’s launch into the U.S. car market and the individual credited by many for the rapid acceptance of Japanese autos by American consumers, has died. He was 105.

Katayama, called “Mr. K” by legions of Nissan enthusiasts, died Thursday at a Tokyo hospital of heart failure, his family announced in Japan.

Born Sept. 15, 1909, in Tokyo to Seishi Asoh and Satoko Katayama, the auto executive joined Nissan Motor Co. in 1935 after graduating from Keio University. He worked in a variety of marketing jobs before being exiled by senior management in 1960 to what looked like a dead-end job in the U.S. because he opposed a company-backed union.

Although the transfer to a risky, nascent foreign market was an obvious demotion, Katayama reveled in his new posting, according to author David Halberstam, who chronicled Katayama’s story in “The Reckoning,” his 1986 book on the auto industry. At the time Nissan sold barely 1,000 vehicles a year in the United States, under the Datsun brand name, through independent distributors. Katayama, known as a savvy marketer and enthusiastic gearhead, turned the company into a household name.

“The efforts made by Mr. Katayama during that early time period had a huge effect on the Japanese auto industry in America,” Kelvin Hiraishi, director of research and development engineering at Mazda North American Operations in Irvine, said in a 2010 interview. “The products weren’t that good, and there was a lot of Japan-bashing going on.”

Katayama took charge of Nissan’s sales efforts for the Western United States, starting with an ad budget of just $1,000, one engineer and an office clerk, according to Halberstam. His first office was in an old Mobil Oil building in downtown Los Angeles; he later moved the business to Gardena. Katayama was known for his long hours and willingness to take on almost any task, whether it was delivering cars personally to the early Datsun dealers or pitching cars door-to-door in Japanese American communities in Gardena and Los Angeles.

It was a daunting task. Most new car dealers didn’t want to take a chance on an unknown import brand of questionable quality. The first franchise was San Diego Datsun, which Katayama described as “a very tiny used-car dealer.” Japanese Americans, whom he thought would be a natural constituency, preferred to purchase American-built cars which they viewed as signaling their pride at being U.S. citizens, he said. Pickup trucks sold best because they were cheap and practical and served as a good third vehicle for many households.

He became Nissan’s top executive in the U.S. when the company combined its East Coast and West Coast operations into one business in 1965.

A racing fan, he quickly established a motor sports team. “That made these cars visible, and it helped that they were [racing against] some of the best names like BMW and Porsche,” Hiraishi said. “It also proved that these cars had durability, which was an image that the Japanese didn’t have.”

Katayama also recognized early on how racing enthusiasts would want to modify the standard Datsun models, and he established a well-stocked competition parts department, Hiraishi said.

Despite his eager sales efforts, Katayama said he wasn’t impressed with the early cars he was selling. He would often say that “quality must be the key to Datsun’s success.” But the initial Datsuns were underpowered and unrefined, even by the standards of the era. He was constantly nagging Nissan for improvements such as bigger engines, better fit and finish, improved brakes — just about anything that would bring the vehicles to the level of the U.S. market. And he was among the first Japanese auto executives to understand that the cars had to be customized for the American driver.

“That was his strength,” Hiraishi said. “He would go back and tell Nissan that it had to produce vehicles that Americans wanted rather than just taking what headquarters wanted to send over.”

Katayama told biographer John Rae, “If I can feed back to the factory, the factory will improve. So, at the beginning, we were in the business of learning something from the United States, then we can make a good car in Japan.”

U.S. consumers would not run out and purchase cars with strange, passive names such as Bluebird and Fairlady when they were also eyeing vehicles with monikers such as Thunderbird or Impala that conjured images of speed and strength.

Indeed, Nissan’s first sports car, the 1969 Fairlady, was named by the company’s president after he’d seen the musical “My Fair Lady,” according to Halberstam. When Katayama’s team got their hands on the vehicles arriving for sale in the U.S., they “simply pried the name tag off the car and replaced it” with a 240Z nameplate based on the company’s internal designation for the car. The sleek two-seater sold for $3,500, was nimble and fast and ushered in a generation of vehicles that redefined the sports-car market. Its success led Nissan to begin focusing on a “sporty” image. Nissan still sells a version of the model — having gone through multiple ground-up redesigns since the late 1960s — under the name 370Z.

Katayama’s years of badgering and pleading paid off in 1968, when the new Datsun 510 models arrived at the Port of Los Angeles. The 510 was a small, durable four-door sedan that performed well and sold for a price — around $1,800 — within nearly everyone’s reach. Automotive buffs compared the car favorably to the BMW 1600, a German-made sedan that sold for about $5,000 in the United States at the time. The 510 ignited a Datsun sales boom, especially in import-friendly market such as California.

The quality, styling and performance of the Datsuns that were shipped to American dealers improved dramatically during the Katayama years.

He remained a maverick in the consensus-oriented corporate culture that dominated the Japanese automaker. And like movie archetypes such as Kevin Costner’s John J. Dunbar in “Dances With Wolves” or Sam Worthington’s Jake Sully in “Avatar,” Katayama went native, to the chagrin of bosses at the home office in Japan. He was an avid fan of American sports such as football and baseball and loved to hike. He also liked to wear cowboy hats.

“We were fortunate to live in Palos Verdes, a very pleasant place, high on the hills, with a sea breeze, above the smog, close to my office, airport and port of San Pedro,” he told The Times in 2010.

Even at age 96, decades after he left the company, Katayama protested the company’s 2005 announcement that it would move its U.S. headquarters from what was then a prominent Gardena office tower overlooking the 405 and 110 freeways to Franklin, Tenn., not far from where it operates an auto factory.

Katayama told The Times that he believed that relocating its California headquarters would cost Nissan “its sensitivity to the [U.S.] car business” by removing key marketing and product development people from an area “considered to be the birthplace of automobile culture.”

After he retired in 1977, Nissan entered what auto industry analysts characterized as a stiff and bureaucratic period when product planning at Nissan headquarters was increasingly bogged down in paperwork and committees. After Katayama, debates between the automaker’s American executives and Tokyo over what types of cars and trucks to sell in the U.S. market became increasingly difficult. Only in recent years has Nissan re-embraced the sporty, product-oriented atmosphere that Katayama pushed, and sales are rising again.

But at times the company would show some reverence for his accomplishments. It brought him back to introduce new versions of the Z sports car, and in 1996 it made Katayama the focus of a $200-million brand-building advertising campaign.

In an interview prior to Katayama’s death, his longtime secretary at Nissan, Johnnie Gable, described him as warm and effusive.

“He never forgets anyone. Once he meets you, he remembers you forever,” Gable told The Times.

Gable said Katayama paid close attention to details, insisting that Christmas cards and invitations be hand-addressed, even when they were going out to a mailing list numbered in the thousands.

He had a playful streak and would sing country and western tunes on the way to dealer meetings and other Nissan events, Gable said. And he could also be generous. “When he went back to Japan he gave me his yellow Z car and I have had it ever since,” Gable said.

After his retirement, Katayama and his wife Masako, whom he married in 1937, moved back to Tokyo and lived close to other family members. He had four children, 11 grandchildren and 18 great-grandchildren.

In the 2010 interview, Katayama told The Times that he still did some sporadic consulting for Nissan but spent most of “my days with Datsun Club members and the Datsun enthusiasts to keep Datsun brand polished up.”

The 1981 corporate decision to rebrand Datsun as Nissan rankled Katayama during his retirement and he kept up with Datsun fans and Z car clubs, traveling frequently to the United States for the events.

“I am grateful that the support of Datsun owners continue for over 50 years and even after Datsun brand had been wiped out by the manufacturer 30 years ago,” he said.

He was driving a Z well after he turned 100, noting that his driver’s license was good through his 103rd birthday.

Katayama was known for ending emails and conversations with the mantra, “Love Cars! Love People! Love Life!”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.