Michael Blake dies at 69; ‘Dances With Wolves’ screenwriter

When Michael Blake was writing his novel “Dances With Wolves,” he was living in Los Angeles on friends’ couches or, sometimes, in his car. He did occasional odd jobs and finally, with $1,000 borrowed from a pal, headed for Bisbee, Ariz., where he washed dishes in a Chinese restaurant for $3.35 an hour.

Agents and publishers had no interest in his novel, a story about the extraordinary transformation of a Union Army hero named Lt. John Dunbar into a Comanche warrior named Dances With Wolves. When the novel finally was published, it was only as a paperback with a cheesy cover featuring a Fabio-like model. Blake was given $6,500 for it.

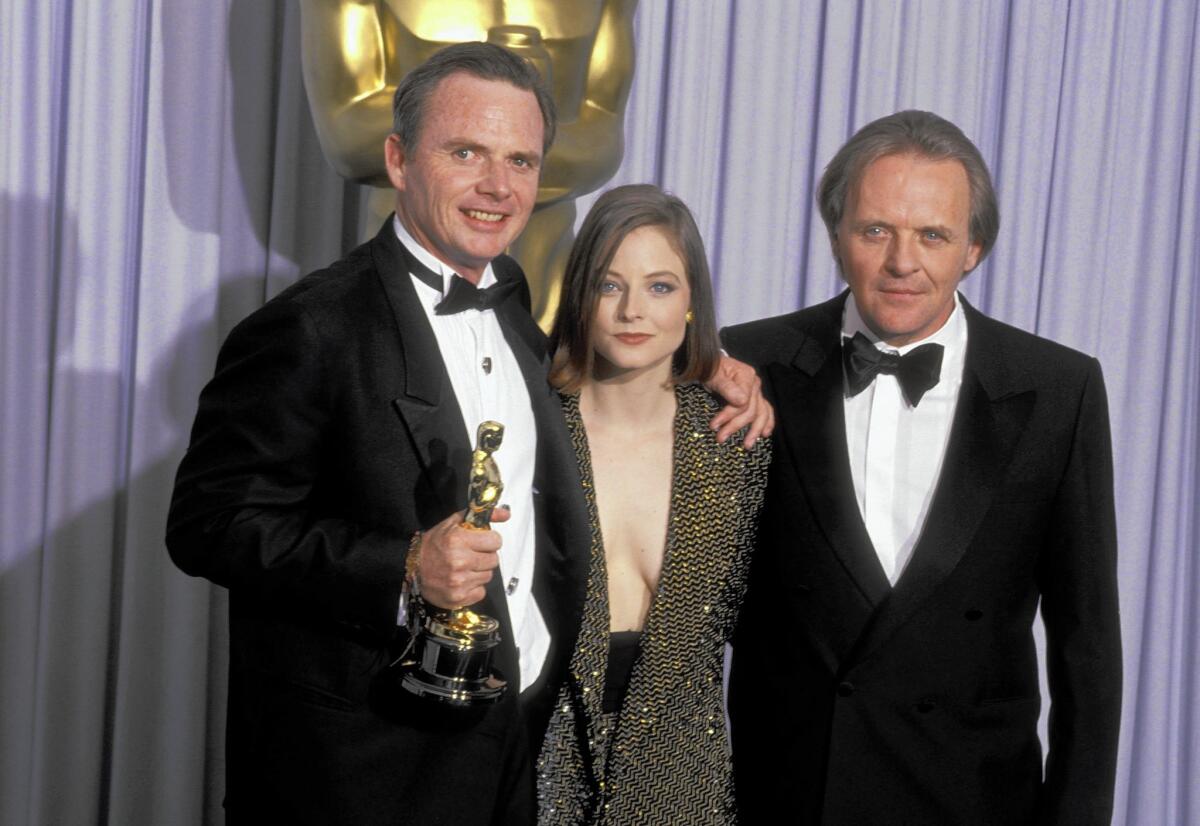

At last tally, “Dances With Wolves” has sold more than 3.5 million copies in 22 languages. Blake won a 1991 screenwriting Oscar for Kevin Costner’s film “Dances With Wolves,” which became the first western to win a best picture Academy Award since “Cimarron” in 1931. Blake went on to publish additional books and advocate for causes related to Native Americans, mountain lions, and the disappearing wild horses of the West.

Blake died Saturday at a hospice in Tucson after a long illness, his manager and business partner, Daniel Ostroff, said. He was 69.

Over the years, Blake had battled Hodgkin’s disease, a form of lymphatic cancer. He also had a double cardiac bypass in 2004.

His other books were mostly fashioned around Western themes. They included “The Holy Road,” a sequel to “Dancing With Wolves” set after the collapse of the buffalo herds vital to the Plains Indians, and “Marching to Valhalla,” a novel in diary form about the final days of Gen. George Armstrong Custer. He also wrote autobiographical volumes including “Airman Mortensen,” about his stint in the Air Force in the 1960s, and “Like a Running Dog,” about his early struggles as a writer.

“The Holy Road,” a reference to the railway tracks cutting across the prairie, is planned for release as a film, said Ostroff, who purchased the rights to it.

Blake “was at least a generation ahead of Hollywood and the audience,” he said.

Blake told interviewers that his fascination with 19th-century Native Americans was triggered by Dee Brown’s 1971 history, “Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee.” He also said that he was intrigued by military historian Wilbur Sturtevant Nye’s “Plains Indian Raiders.”

“In it, an anecdote told about a wagon driver who had driven out on the frontier to supply an outpost in western Kansas,” Blake wrote in a recollection on his website. “But when he arrived, he saw that no one was there; the only sign of life was a piece of canvas flapping in the breeze.

“That image somehow moved me, and I started thinking about it, filling it in with other images. I asked myself, what if I was on that wagon, and that was going to be my new post, what would happen then? The seed was planted for ‘Dances With Wolves.’ I became Lt. John Dunbar and through him, I had the experiences that I wanted so much to have.”

Michael Lennox Blake was born in Ft. Bragg, N.C., on July 5, 1945, and grew up at various spots in Southern California. He attended the University of New Mexico but in his senior year left for Los Angeles, where he wrote for the Free Press, an alternative newspaper.

Blake later took film classes in Berkeley, where in 1977 he became friends with Jim Wilson, a fellow student who went on to become a producer.

In the early 1980s, Blake was back in Los Angeles, writing a film about gamblers. The film, “Stacy’s Knights,” was produced by Wilson and starred one of his friends, the then-obscure actor Kevin Costner.

When Blake told Costner his idea for a movie about an encounter between a former soldier and Indians on the remote prairie, the actor urged him to write a novel instead of a screenplay.

“I’d written probably 15 screenplays by that time,” Blake told the New York Times in 1991. “He said, ‘Write a book. You have a much better chance of reaching somebody with a book.’ He was adamant. He was even shaking his finger at me as I left the house that night. So a couple of weeks later, I started writing it.”

The novel was set in Oklahoma with members of the Comanche tribe. The setting was changed to South Dakota for the film largely because Oklahoma lacked the buffalo required for the story. Nearly half the dialogue was in Lakota, a Sioux dialect, with English subtitles — a feature that at first put off U.S. producers.

“This story is so American we had to go to Europe to get the initial money,” Blake told the Seattle Times in 1990.

Although the movie, which cost $18 million to make, received a few lukewarm reviews — the New Yorker’s Pauline Kael said the main character should have been called “Plays With Camera” — much of the reaction was stunningly positive. At the box office, it was a huge success, grossing more than $424 million worldwide.

Blake bought a ranch near Tucson and moved there with his wife, Danish-born painter Marianne Mortensen Blake.

In addition to Marianne, his survivors include his brother Dan Webb, and three teenage children: Quanah Valdemar Blake, Monahsetah Dagmar Blake and Lozen Ingefred Blake.

The children’s first names are those of Native American heroes and their middle names are Nordic.

[email protected]

Twitter: @schawkins

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.