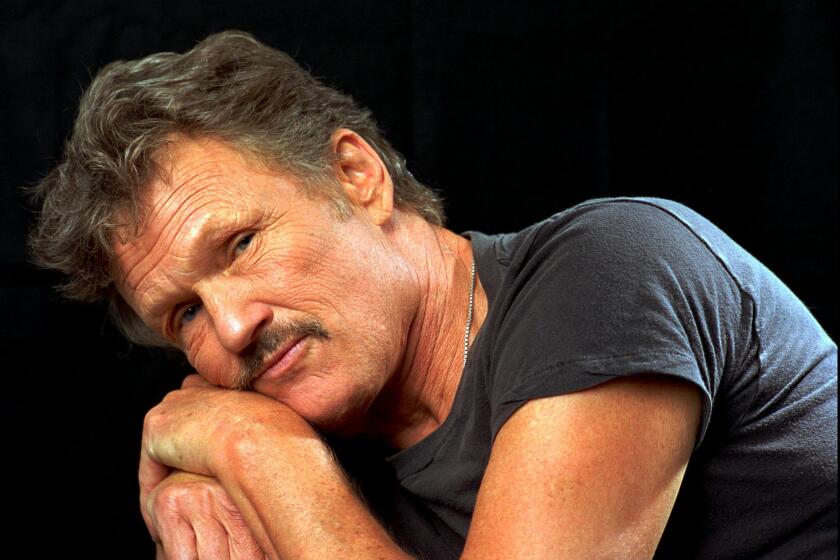

Bruce Lundvall dies at 79; jazzman revived Blue Note Records

Bruce Lundvall’s youthful ambition to become a jazz musician led him first to the trumpet and the piano and then to the saxophone, each proving to be a fruitless quest.

In later years, even as he soared as a recording executive, he would describe himself as a “failed saxophone player.”

But Lundvall fulfilled more far-reaching ambitions when he reached into the business world of jazz.

“I was a big record collector, a bad saxophone player, and all I wanted to do was be in the music business,” he said in an interview with Bucknell Magazine, the periodical of his alma mater.

Lundvall, who became a deeply influential and highly visible executive at Columbia Records, Blue Note Records and other major labels, died Monday at Valley Hospital in Ridgewood, N.J. His biographer, Dan Ouellette, reported that Lundvall died from “complications from a prolonged battle with Parkinson’s disease.” He was 79.

Over the course of a career that touched virtually every aspect of the music world, Lundvall was seen as a jazzman at heart who had finely tuned business instincts. Praised by the performing artists whose careers he touched, as well as the lawyers and deal makers who had their own agendas, he moved from one lofty record company job to another, leaving his mark along the way.

“Bruce speaks the language of musicians,” jazz singer Dianne Reeves told Bucknell Magazine. “He’s all in the music; he’s part of the blood of it.”

Bruce Gilbert Lundvall was born Sept. 13, 1935, in Cliffside Park, N.J., the eldest of Howard and Florence Lundvall’s three children. In 1949, the family moved to Glen Rock, N.J.

He was drawn to jazz during a period when the jazz world was being shaken by the arrival of bebop and the influential playing of such iconic artists as Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Bud Powell and Thelonious Monk. Captivated by the new sounds, Lundvall used all his spare change to buy the artists’ recordings. By the time he reached his mid-teens, he was finding ways to get into night clubs to hear them perform.

At Bucknell University in Pennsylvania, where he studied commerce and finance, Lundvall produced jazz concerts and his own radio show. After graduating from Bucknell and serving in the U.S. Army, he obtained his first significant position in the record business – an entry-level marketing job at Columbia Records – in 1960.

Over the next two decades, Lundvall ascended to become vice president of marketing, then president of the domestic division of CBS Records, affording him the opportunity to delve deeply into the vibrant jazz of the period. Lundvall made the most of it, creating a far-reaching, highly praised catalog of recordings that established Columbia’s identity as a major producer of jazz and diverse contemporary music.

Reaching across the musical spectrum to bring in new talent or re-sign established artists, he signed Miles Davis, Wynton Marsalis, Phoebe Snow, Willie Nelson, Dexter Gordon and Bruce Springsteen and oversaw Herbie Hancock’s first electronic rock efforts.

In 1982, Lundvall became president of Elektra Records, along with the company’s new Elektra/Musician Jazz label. In his relatively short stint on the job, he established Elektra’s authenticity as a jazz label.

Two years later, he received an offer from EMI that he couldn’t resist. It called for him to create a new label – Manhattan Records. In addition, and perhaps most exciting of all to Lundvall, it called for him to partner with producer Michael Cuscuna in the revival of Blue Note Records, a great jazz imprint that had lost its once-proud jazz authority.

Given Lundvall’s early affection for bebop and bebop-tinged music, he elected to bring some of the earlier Blue Note bebop icons back to the label – including Freddie Hubbard, Jackie McLean and Joe Henderson.

But he was equally receptive to preconceiving the revived Blue Note as a home for new talent, as well. He took off on that path with the booking of a then-unknown singer named Norah Jones, whose only apparent claim to fame was that she was Ravi Shankar’s daughter.

Jones’ first album, “Come Away With Me,” sold more than 11 million copies and earned eight Grammy Awards.

And Lundvall didn’t hesitate to sign other gifted young talent, including jazz artists Robert Glasper, Ambrose Akinmusire, Jason Moran and Greg Osby, as well as crossover acts such as Al Green and Amos Lee.

“Bruce was one of the greatest music industry visionaries of the 20th century,” recalled Herbie Hancock. “He made the impossible possible with Blue Note Records. Because of Bruce so many artists that you never expected to be on a jazz label are appearing on there now. He was never just interested in money. He truly loved good music and loved jazz.”

After leading Blue Note for nearly three decades, Lundvall – dealing with the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease – stepped down in 2010 and was replaced by musician and producer Don Was.

“Bruce was a one-of-a-kind, larger-than-life human being,” Was said in a statement. “His joie de vivre was equaled only by his love for music, impeccable taste and kind heart.”

Lundvall’s biography, “Playing By Ear,” written by Ouellette, was published by ArtistShare in 2014.

Lundvall served as chairman of the Recording Industry Assn. of America, chairman of the Country Music Assn. and director of the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences. He won lifetime achievement awards from the Jazz Foundation of America and Down Beat and received the UCLA Gershwin Award and a Grammy Trustees Award.

Lundvall is survived by his wife, Kay; sons Tor, Kurt and Eric; and two grandchildren.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.