Blues legend B.B. King, inspiration to generations of musicians, dies at 89

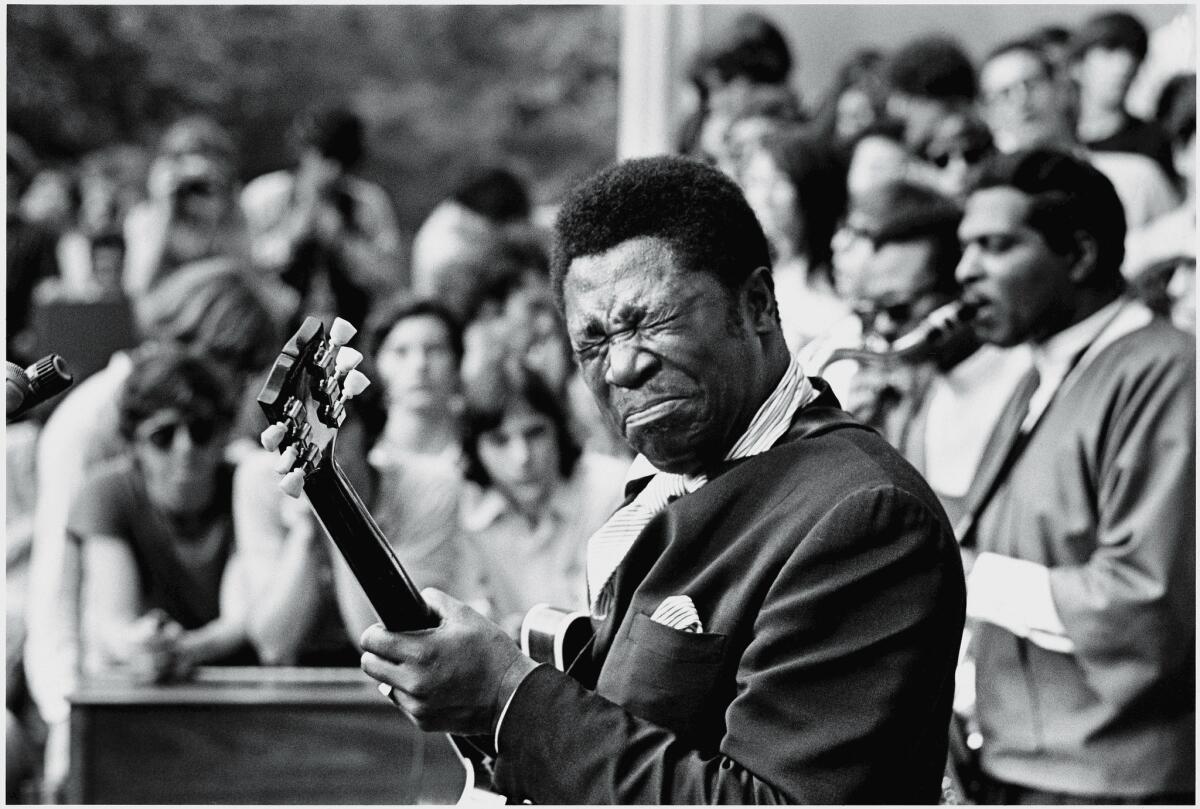

B.B. King, whose performances took him to small and large cities alike, plays the guitar at Central Park in New York in June 1969.

B.B. King, the singer and guitarist who put the blues in a three-piece suit and took the musical genre from the barrooms and back porches of the Mississippi Delta to Carnegie Hall and the world’s toniest concert stages with a signature style emulated by generations of blues and rock musicians, has died. He was 89.

The 15-time Grammy Award winner died Thursday night in his Las Vegas home, said Angela Moore, representative for his youngest daughter, Claudette. He had struggled in recent years with diabetes.

King died peacefully in his sleep, Claudette King told The Times.

PHOTOS: B.B. King | Life in Pictures

Early on, King transcended his musical shortcomings — an inability to play guitar leads while he sang and a failure to master the use of a bottleneck or slide favored by many of his guitar-playing peers — and created a unique style that made him one of the most respected and influential blues musicians ever.

“B.B. King taps into something universal,” Eric Clapton told The Times in 2005. “He can’t be confined to any one genre. That’s why I’ve called him a ‘global musician.’”

Because King couldn’t figure out how to play and sing simultaneously, he separated the two functions, laying the blueprint for the sung verse followed by the extended solo passage that would become a crucial element in blues as well as in rock music rooted in the blues. That template was exploited by subsequent generations of players, from Clapton and Jimi Hendrix on through to John Mayer and the Red Hot Chili Peppers.

Finding that he couldn’t make his elegantly long but thick fingers work the beer bottlenecks and metal slides used by so many other blues guitarists, he discovered that he could emulate that effect by rocking the fingers of his left hand rapidly on the guitar’s frets similar to the way a classical violinist creates vibrato, establishing a ringing tremolo that became his hallmark.

That guitar, a black Gibson hollow-body instrument he named Lucille, became one of the most famous in all of popular music, as central to his public persona as his rotund physique, twinkling eyes and wide-eyed grin that served as a counterpoint to the soul-deep ache at the heart of much of his music.

King spent decades honing the craft that helped him escape the poverty of the Deep South, where he grew up on a Mississippi plantation as the son of a sharecropper who became a teenage sharecropper himself before singing and playing his way out of the cotton fields.

He was an indefatigable performer who seldom left the concert trail for more than a few days at a time. In 1956 he played 342 shows and even in his later years kept a schedule that would test the endurance of musicians half his age.

In part, it was because he said he had an addiction to something called “need more,” but it also reflected his lifelong drive to bring respectability to a form of music disparaged in his youth as “the devil’s music” and disrespected during his adulthood as “the music of the ghetto.”

“People thought I was truly a workaholic,” King told The Times in 2005. “But I never got the exposure in my kind of music [given to] other types of music that are exposed daily in the media.… I’ve had one record that was played like other records. It was called ‘The Thrill Is Gone,’ the only one I ever had that was played on radio stations like other types of music, unless I was playing with somebody else.”

He tapped his music and oversized personality in transcending the limitations of a genre that rein in most blues musicians, forging an international identity as a beloved cultural ambassador. King collaborated with hundreds of musicians in most fields of pop music, culminating with his 1989 teaming with U2 on the Irish rock quartet’s single “When Love Comes to Town,” which brought him to the attention of millions of young rock fans when he was in his mid-60s.

Decades earlier, when black audiences largely moved away from listening to the blues in favor of R&B and soul performers such as James Brown and Ray Charles, King’s flagging career was resuscitated when the Rolling Stones, the Animals, Clapton, Van Morrison and other white rockers of the British Invasion started singing the praises of King and other American blues musicians to their young fans.

That put King in front of an entirely new audience, and after he put out his version of the Lowell Fulson song “The Thrill Is Gone” in 1969, King went to the upper reaches of the national sales charts and in 1971 collected the first of a string of Grammy awards.

::

Riley B. King was born Sept. 16, 1925, on a cotton plantation between Itta Bena and Indianola, Miss. As a young teenager he could pick nearly 500 pounds a day, earning 35 cents for every 100 pounds he picked.

-----------

FOR THE RECORD

6:56 a.m.: An earlier version of this obituary stated that B.B. King was born on Sept. 25, 1925. He was born on Sept. 16 of that year.

------------

After he learned to drive a tractor, he upped his pay to $22.50 a day. After enlisting and serving briefly in the Army during World War II, he was discharged by the draft board because tractor drivers were more valuable as civilians.

King often cited the plantation owner, Johnson Barrett, as one of the key male role models of his youth, and it was Barrett who advanced him $30 so he could buy his first guitar. “My Darling Clementine” was the first song he learned to play, at first replicating and then synthesizing what he liked in recordings by jazz guitarists Charlie Christian and Django Reinhardt with those of blues players such as T-Bone Walker and Lonnie Johnson. Initially, he played and sang in church and with gospel groups including the Famous St. John Gospel Singers.

He took his guitar into the big city of Indianola and staked out a corner, where he played for change from passersby. King learned quickly that people threw more money when he changed the word “Lord” in his gospel songs to “baby” and turned them into secular love songs.

He dropped out of high school at 15 because he could make more money playing for a night than he got for a full day’s work on the plantation. After a visit to Memphis, Tenn., in 1946, he set his sights on paying off his sharecropping debts and moving north to try his luck, and to escape the racial violence he had witnessed in Mississippi.

He started performing in Memphis with musicians including singer Bobby “Blue” Bland and pianist Johnny Ace and soon caught the attention of blues man Sonny Boy Williamson, who had a radio show on WDIA, the first U.S. radio station to adopt an all-black music format.

King became known as “the Blues Boy of Beale Street,” then the Beale Street Blues Boy, shortened to Bee Bee King for his on-air nickname, and later simply B.B. King.

He signed to Memphis-based Bullet Records in 1949 and recorded four songs at the radio station’s studio, including “I’ve Got the Blues” and “Miss Martha King.” While he was playing a barn dance that year in Twist, Ark., a fight broke out between two men in which a lantern was knocked over, setting the barn on fire. King and the others escaped, but he raced back into the blazing structure when he realized he left his guitar behind. When he found out that the men had been fighting over a woman named Lucille, he gave the name to his guitar “to remind myself never to do anything that foolish.”

That particular guitar was stolen two years later, but he kept the name for every instrument he used onstage after that, and the Gibson company eventually made it official by creating its B.B. King/Lucille model.

In 1951, King connected with Sam Phillips, a music fan and engineer who had just built his own recording studio in Memphis that eventually would become Sun Records, where Phillips discovered Elvis Presley, Jerry Lee Lewis, Johnny Cash, Roy Orbison, Carl Perkins and other early rock ‘n’ rollers.

But before Sun went rock, Phillips was busy capturing the excitement of the blues musicians including King, Howlin’ Wolf, James Cotton and others who had flocked to Memphis. He recorded what would be King’s first hit, “3 O’Clock Blues,” released on the Modern label. That took King to the top of Billboard’s R&B chart for five weeks and opened the door for a full-fledged music career.

From the beginning, he railed against the down-home image many blues players projected, opting instead to model himself on the big-band leaders he so admired, typically appearing onstage in stylish three-piece suits, and requiring his band members to wear the same.

“I never did see Duke Ellington with overalls or jeans on,” King said. “I never saw Benny Goodman with any on. Nor did I see Count Basie or Lionel Hampton or Glenn Miller with overalls or jeans. I always thought, from the older musicians I talked to, that you should look different [on stage] than you would in the street. And I like that.”

The urban sophistication he brought to the blues brought some detractors, who criticized him for catering to white audiences, with some blues purists preferring the unadulterated approach of such predecessors as Robert Johnson and Charley Patton or grittier peers such as Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf. But King’s expansive vision also helped take the music far beyond its regional and racial origins.

From 1951 to 1961, he scored 19 more Top 10 R&B hits, but his traditional blues couldn’t compete for a mass audience against the dynamic R&B of James Brown, the sexually charged rock of Little Richard or the playful teen-centric poetry of Chuck Berry.

Even among black audiences, he found there was a stigma against musicians who played the blues. “People are so class conscious,” King told Leonard Feather, then The Times’ jazz critic, in 1970. “They associate blues with the ghetto. They don’t respect it. Certain black audiences, before they’re willing to give you credit, they wait until the media have picked up on you.”

It was a different story across the Atlantic Ocean. There, young white musicians, enamored of the music they heard on records by King, Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Lightnin’ Hopkins and other blues masters, funneled their influence into new music that soon stormed the charts on both sides of the sea. And when they talked about where that music originated, King found a new level of appreciation for what he was doing.

“When you mention the Rolling Stones, I get on my knees,” King said in 2005, “and say, ‘Thank you, thank you, thank you.’ Because before them, we didn’t get the [attention] we do now.”

The ball kept rolling after “The Thrill Is Gone” gave him an across-the-board hit. He recorded more than 50 albums — King said he lost count long ago — and was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1987. He collected a lifetime achievement award from the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences in 1988, the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1990 and a National Heritage Fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts in 1991.

King was married twice — to Martha Lee when he was 17 and then Sue Hall when he was 32. Each marriage lasted about eight years.

He had 15 children, Moore said.

Staff writer Ryan Parker contributed to this report.

ALSO:

Tributes pour in for B.B. King

The B.B. Box’s influence on guitarists

The story behind B.B. King’s beloved Lucille

Five tracks to hear beyond ‘The Thrill Is Gone’

B.B. King on dying: ‘I pray to God it’ll happen one of three ways’

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.