This story is part of Image’s August issue, Lineage, about intergenerational conversations and how they shape us.

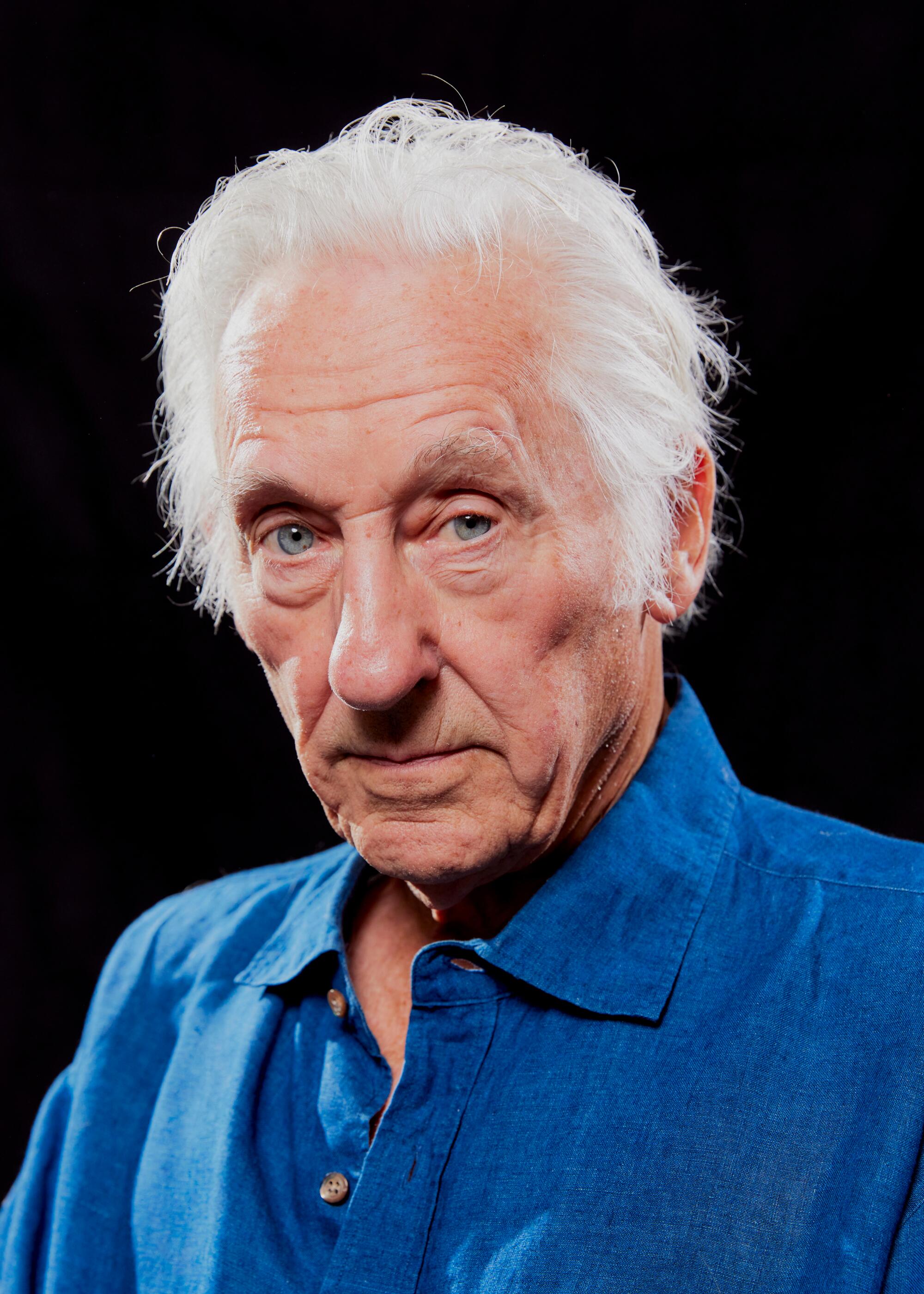

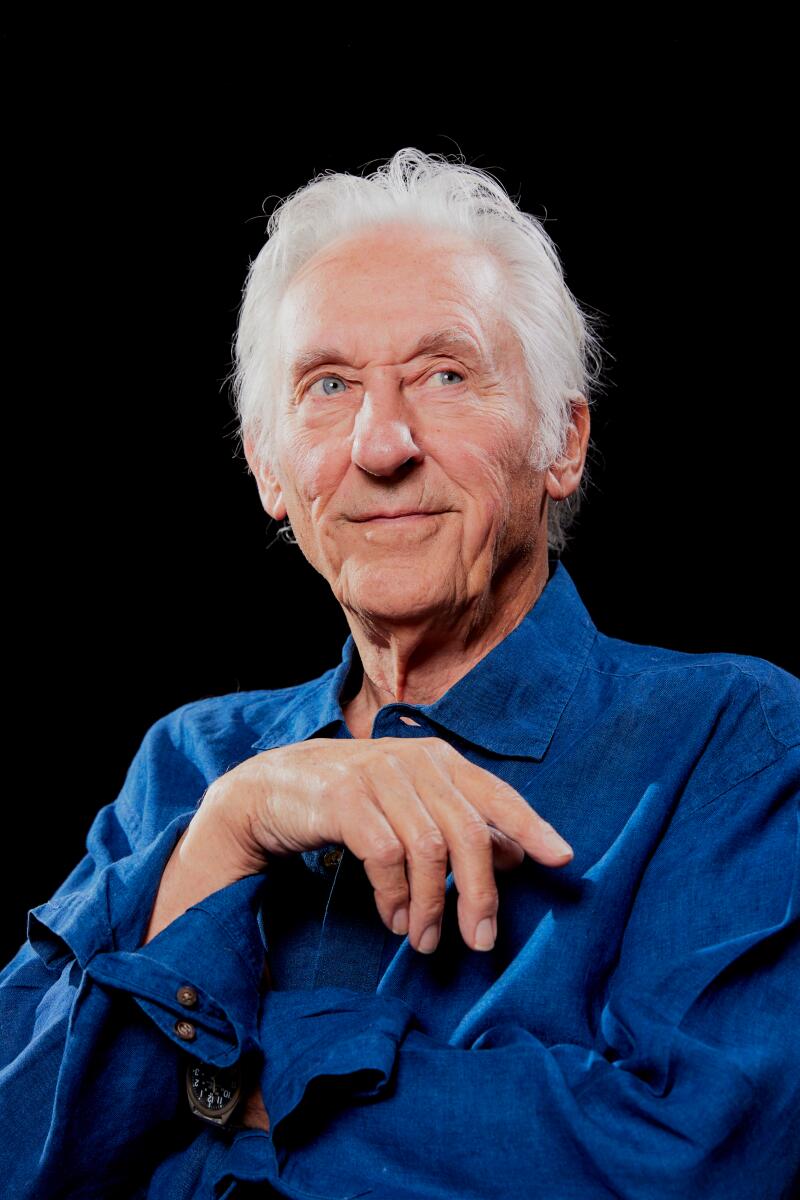

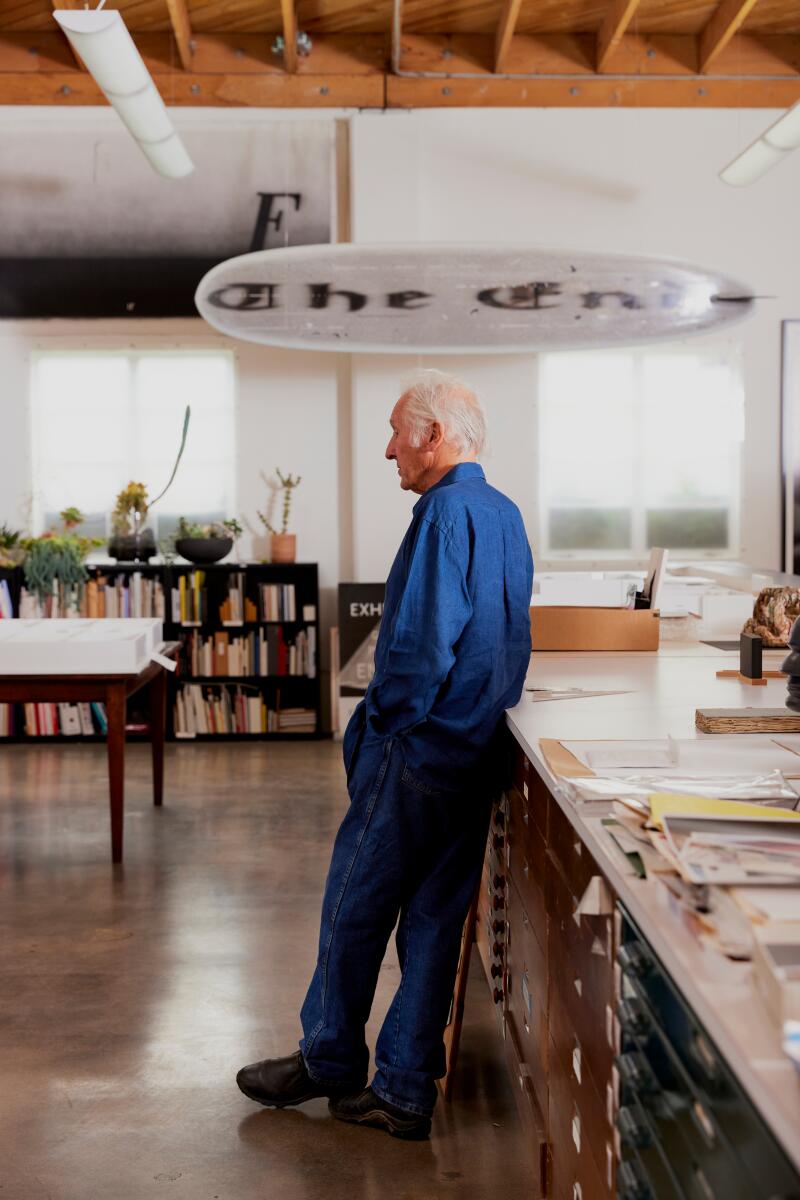

Ed Ruscha loves plants. If you know his art, this fact might come unexpected. He’s not a landscape artist. He’s never wanted to paint a plant. “I’m not sure why,” he says from behind the large desk in his Culver City studio. And yet he’s been gardening for some 50 years.

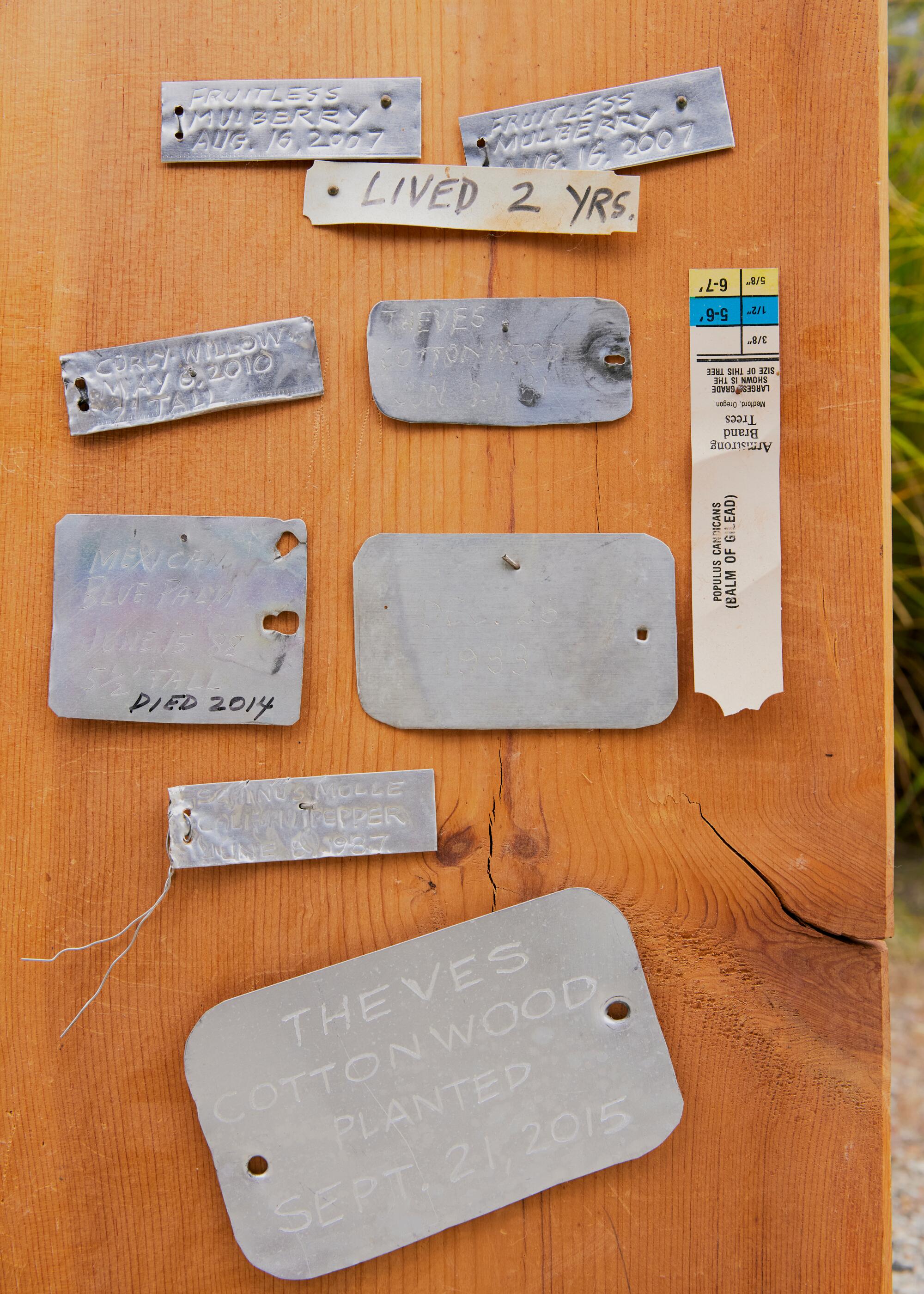

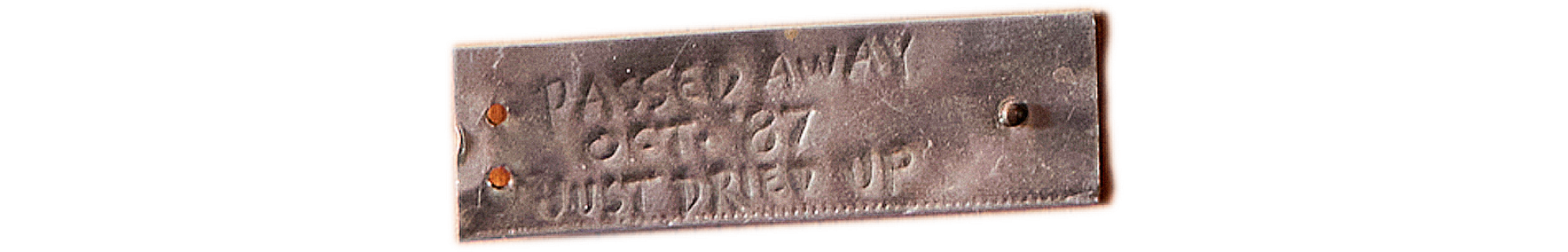

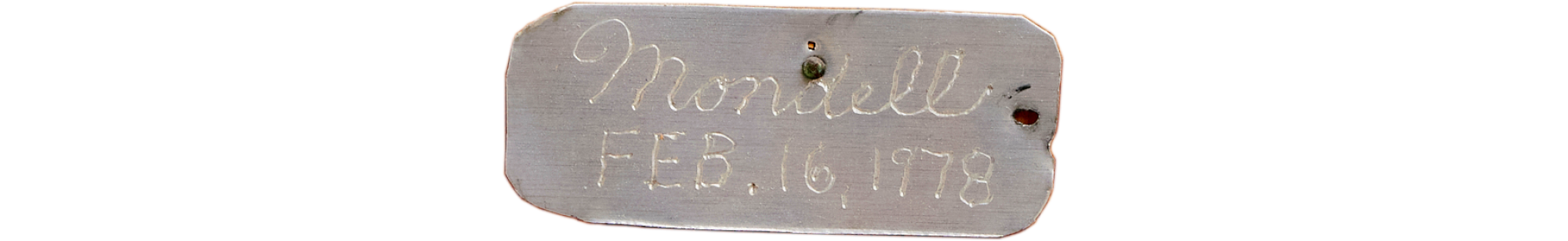

We’re looking together at two wooden planks with metal tags hammered into them. Each tag once belonged to a plant that has died, the shiny metal carved with the name of the plant, the date of its death and sometimes its cause: “Passed away / Oct. ’87 / Just dried up.”

“They’re like little epitaphs for the departed,” Ruscha says. At the top of one board, he has written: Trees and Plants that Didn’t Make It.

He grows his plants out in the desert, in the Yucca Valley, where he has a cabin. Ruscha “found out the hard way” which plants survive in the arid climate with sand storms and even snow. “I should know better than to plant a palm tree in the high desert.” He looks straight at me with his blue eyes, then smiles, briefly.

The L.A.-based photographer and artist tells us the story behind her rare Danish designer chair and why chairs “are everything.”

Ruscha creates a tag each time he acquires a plant, a label to remember its species, and then pokes it into the ground for as long as the plant will last. He enjoys the process of tending to his plants, protecting them from raccoons with barriers made of wire. He likes the challenge of seeing if he “can make something survive,” especially something “as delicate as a plant.”

I ask Ruscha if it makes him sad when a plant dies. “Yeah, I shed a tear,” he says — earnestly, I think. “A quick tear. And then it gets posted to the board here.” He keeps the boards leaning against the wall in his studio. “I check it out and nod at it every so often to let it know I care about it,” he tells me. “And I’m getting smiles in response” — his eucalyptus, mulberries and bird of paradise appreciating him in the afterlife.

The more I sit with Ruscha’s epitaphs, the less unexpected his love for plants becomes. Time, after all, is the artist’s great subject.

Ruscha’s life-spanning retrospective currently at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art is called “Now Then,” evoking his black-and-white lithograph of the phrase “That was then, this is now” lit up against dark clouds. His pictures declare the way things evolve and age, from a dramatic painting of the words “The End” to images of everyday, discarded things, like a torn mattress or broken pencil.

Looking for proof of life amid the candy-coated anti-depressants of suburbia.

Ruscha tells me about his blazing red 1983 painting with the words “The Study of Friction and Wear on Mating Surfaces.” He makes the connection: “You could almost say the wind is a mating surface of a plant. And that intrigues me and probably motivates me.”

This idea of motivation comes up, subtly, throughout our conversation. At 86, the drive to keep his plants alive, and his sense of purpose in caring for their death, keeps him going.

I ask Ruscha if he considers himself nostalgic. “I like remembering the past and the way things used to be,” he answers, establishing a gentle, precise distinction. He’s made a ritual of going out in Los Angeles and noticing how the landscape has changed. “I compartmentalize the way the city looked at one time,” he says, which, when he moved here in the 1950s, was like “some kind of antique village.”

Most famously, Ruscha has been photographing every block of Sunset Boulevard since the 1960s, marking the gradual disappearance of buildings, honoring street corners as his tags do for his trees. “I should have been tagging all these buildings too!” he suddenly realizes. “But we’ll let the graffiti artists tag.”

“I like remembering the past and the way things used to be,” says Ruscha.

Ruscha is not against change per se, but he’s found the need to notice it. It’s an act of observation, rather than an indulgence in longing — an exercise in remembering, an effort to place things within a continuum.

Nonetheless, change can be tiring, and Ruscha seeks a break from it by going to the desert. It’s a contrast to his life in L.A.; he doesn’t see people in the desert, and, unlike a city, it’s mostly changeless. Its rocks have been there for thousands of years. It doesn’t feel like a coincidence that it’s in this stubborn landscape where Ruscha has chosen to grow his garden, where plants try to thrive against all odds, their cycle of life and death against a seemingly stable backdrop.

“I think about how catastrophic thinking can be generative, how to not keep it in the loop, but to bring it out into something else,” says Chang.

“It’s not just the plants that I like, but it’s the labeling,” Ruscha shares with me about his board. He excitedly explains how he etches the tags with a metal machine. “They’re not going anywhere. … These are permanent.” Like the desert to the city, the tags are the comforting counterpoints to his plants, changeless.

When people think of Ruscha’s art, they think of how iconically L.A. it is — his painted Hollywood signs, sleek gas stations and swimming pools. But it’s also iconically the desert. His art — and I include these humble wooden planks — has the energy of a desert, of those rocks that persist. I think it’s in the sharp light, in the way things get fixed.

Ruscha, who grew up in Oklahoma, moved to L.A. when he was 18 years old and hasn’t left since. He’s found himself having to explain why he didn’t move to a bigger art center like New York City and chose, instead, to stay. It’s “the feeling of California,” he tells me — “including its vegetation.” In describing the cactuses and the palm trees, he notes “the laciness of it all. … It has a magic to it that attracted me.”

While at his studio, he walks me back to his second garden, the concrete backyard that once upon a time was an orange grove. He shows me a row of Joshua trees sprouting in pots, which he plans to take with him to the desert. Holding on to his two wooden planks, he sits among kumquat and lime trees. With his all-blue outfit and bright white hair and eyebrows, he has his own magic laciness about him.

“You know, I think I get emotional progress, emotional propulsion, from plants,” he tells me. By the end of our time together, I’m getting used to how he casually utters such profound statements. I’m with the softer side of an artist known for having the cool, edgy swagger of his art, the side that propels him to paint large canvases of cracks in the sidewalk and that declare “The End” of things. It’s the side of him that picks up a basket of kumquats and limes and distributes them, one by one, into a paper bag for me to take home. It’s his nature-loving side, seemingly behind the scenes, driving how he creates and lives.

“I feel powerfully connected to that board,” Ruscha concludes. “[A] lot of plants have died, but they all are sort of reminders to me — once with me and now departed. So that’s OK.”

Photo Assistant Cody Rogers