On a visit to Los Angeles, the photographer Paul Yem recalls driving through the city and feeling his “photo eyes wake up.” He notices a woman watering her lawn, “a 10-by-10-foot brilliantly green grass lawn,” and she is wearing a bright red dress and big sunglasses. “It looked like out of a scene of a movie,” Yem says. He’s trying to illustrate what he calls “manufactured happiness” — this idea that we have turned to our houses to give us what we think happiness should look like: manicured lawns, freshly painted facades, spacious garages. Yem spent days photographing these houses throughout Los Angeles, which he describes as “candy-coated anti-depressants.”

Yem’s photos join a tradition of art made about L.A. architecture and home life: Ed Ruscha’s photos of Sunset Boulevard and Pop-like paintings of Hollywood; David Hockney’s paintings of luxurious days by the pool side. In another sense, Yem also joins the photographers who documented the modernist single-family home in L.A. throughout the 20th century, like Julius Shulman and Maynard L. Parker. But Yem’s photos are more spiritually in line with works by artists like Janna Ireland and Ramiro Gómez Jr. — artists who search for and insert the human stories behind the overly polished suburban landscape.

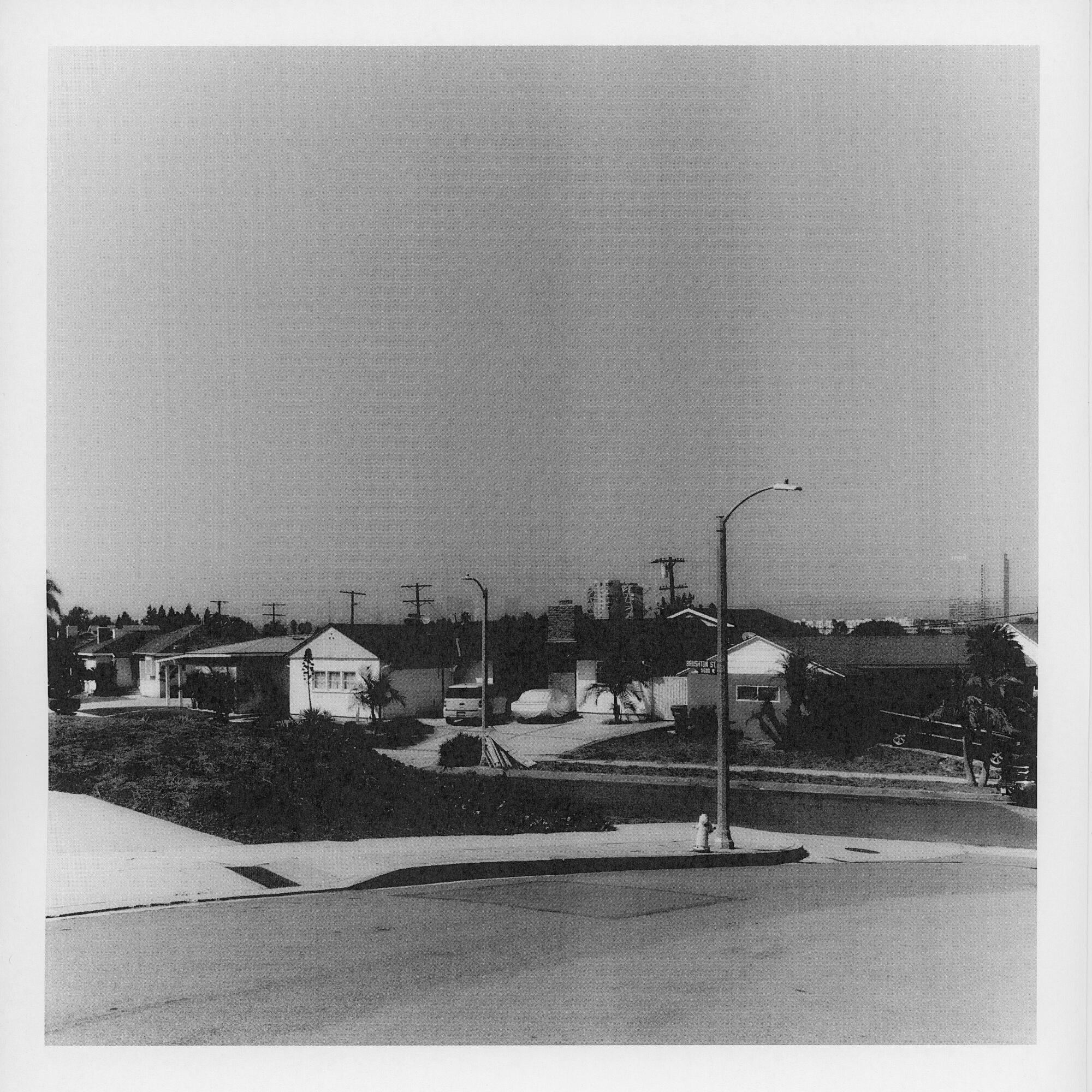

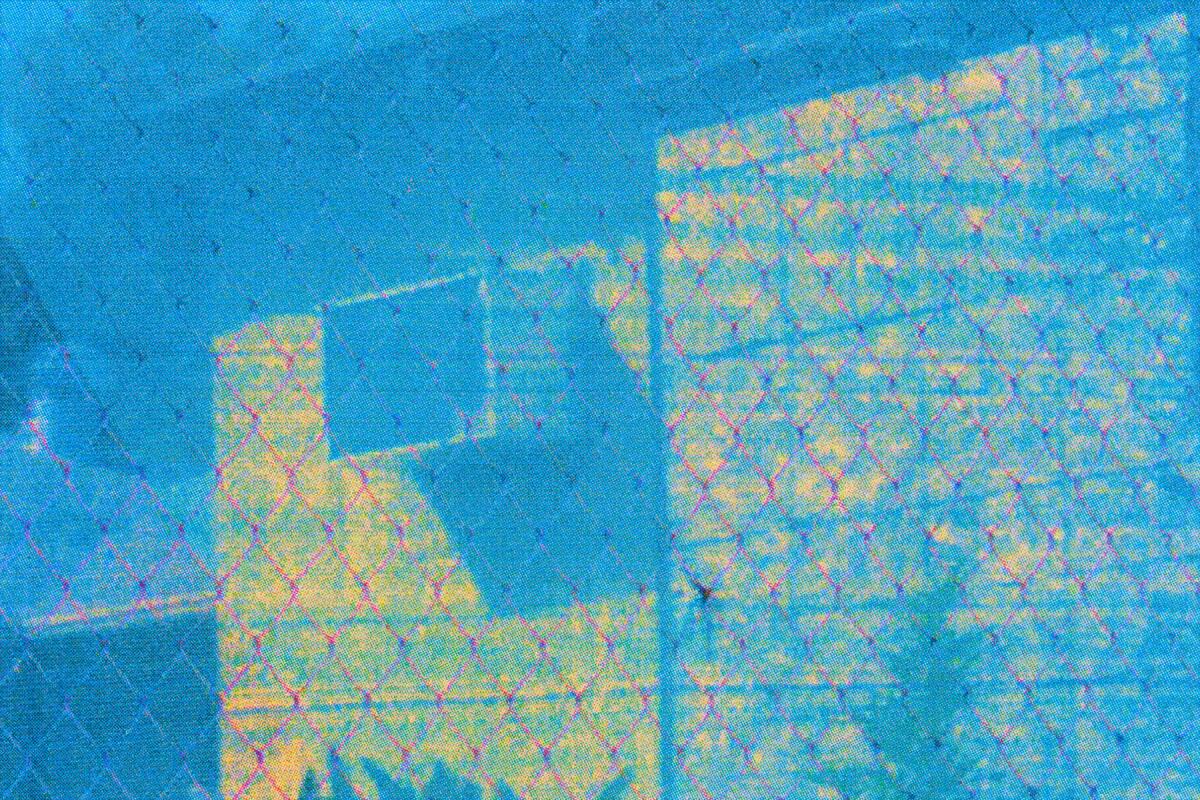

Through Yem’s eyes, we move through L.A. and the suburbs in different registers, from a nostalgic black and white, to a soft, tender blur, to a clinical brightness, to a saturated mirage. They are beautiful and disquieting, like an American dream.

Elisa Wouk Almino: What moved you about these houses to stop and look and capture them?

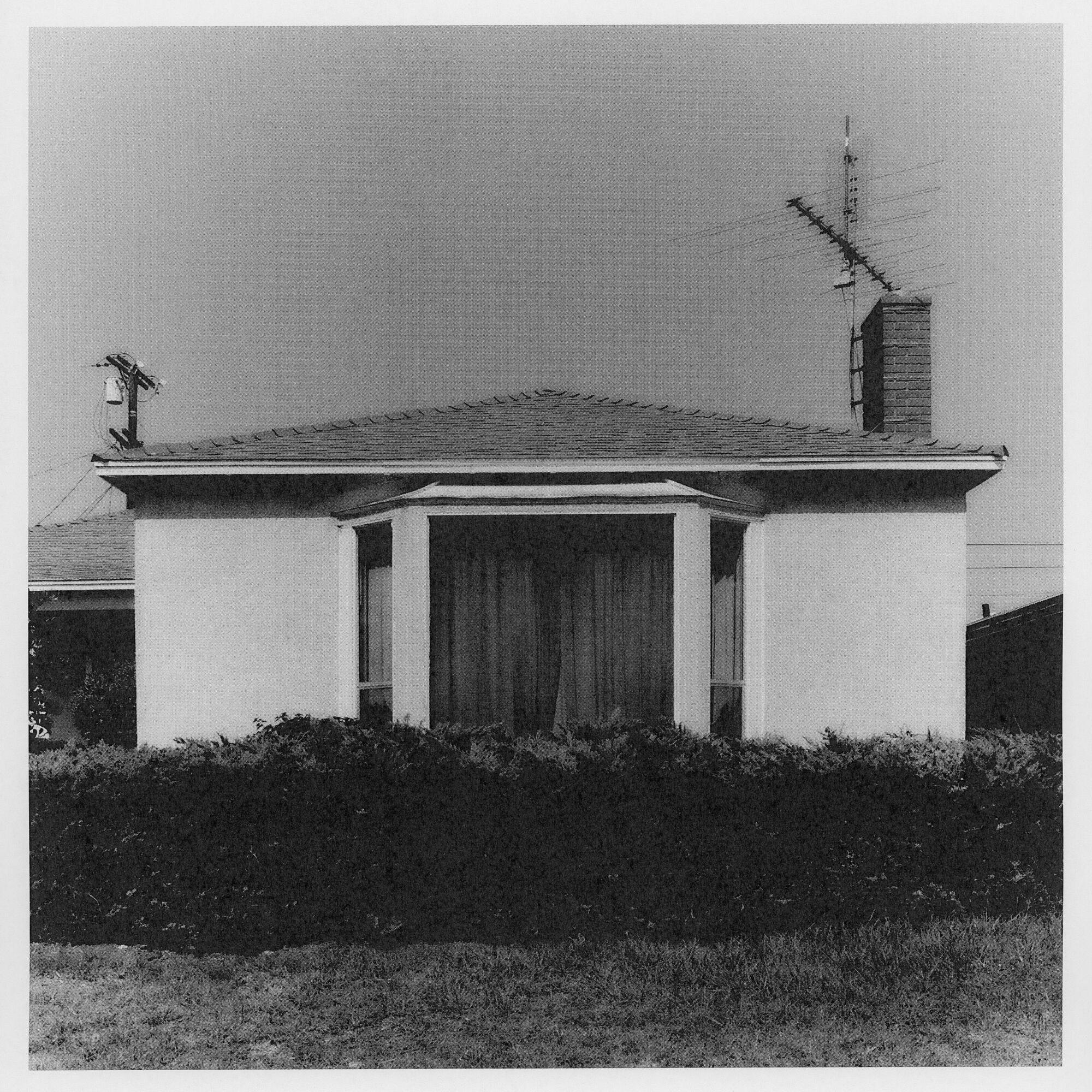

Paul Yem: What I wanted to look for was this trace of a human element. As I drove around, the thing that struck me immediately was that these neighborhoods are deserted. The human element is the absence of humanity. [As] I was lying in bed one night, I was like, what am I looking at? And it was really the idea that this suburbia is a community, it’s a sort of fabricated community, and to me, the more contrived it was, the less human it was.

Janna Ireland’s practice is a way of seeing and being comfortable in the world.

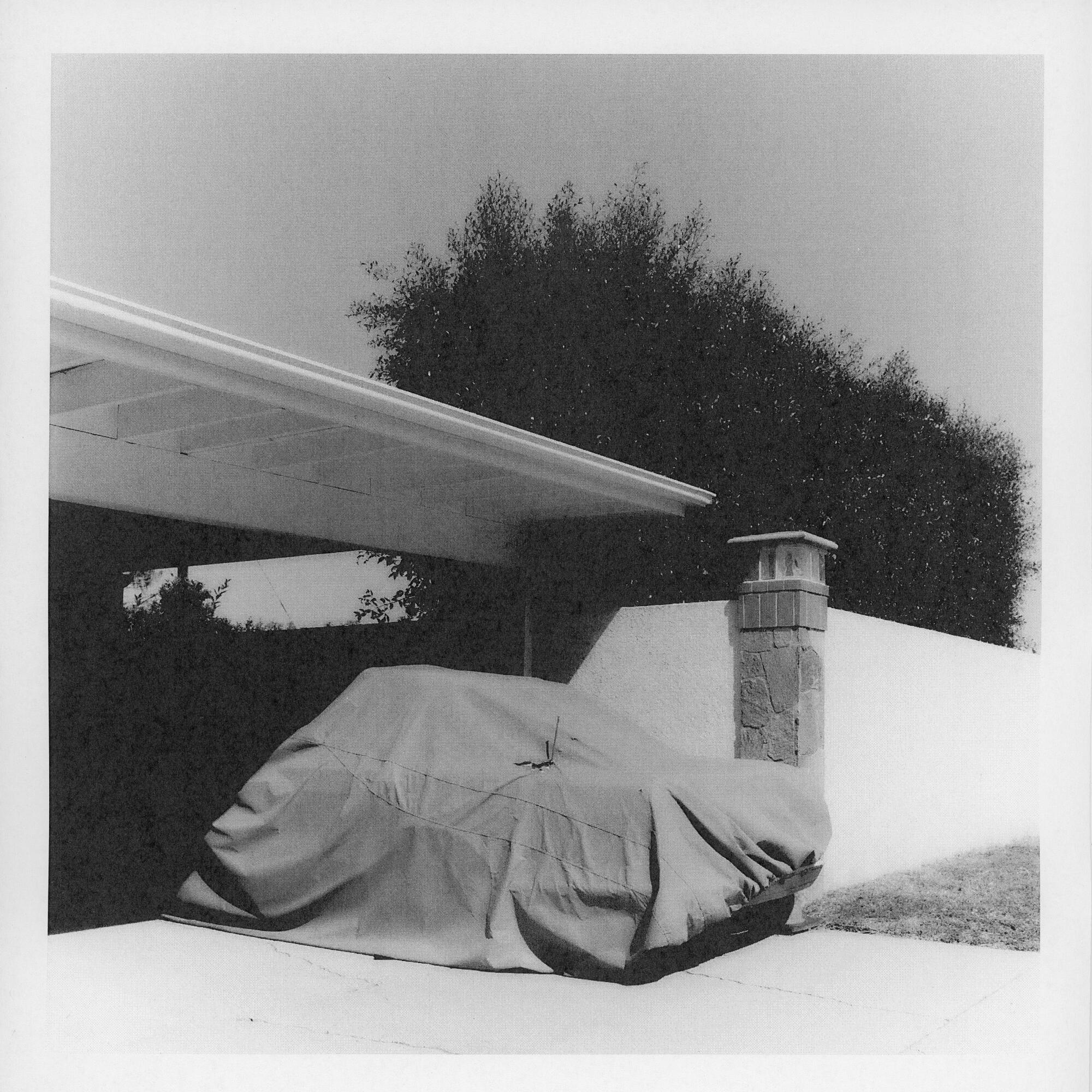

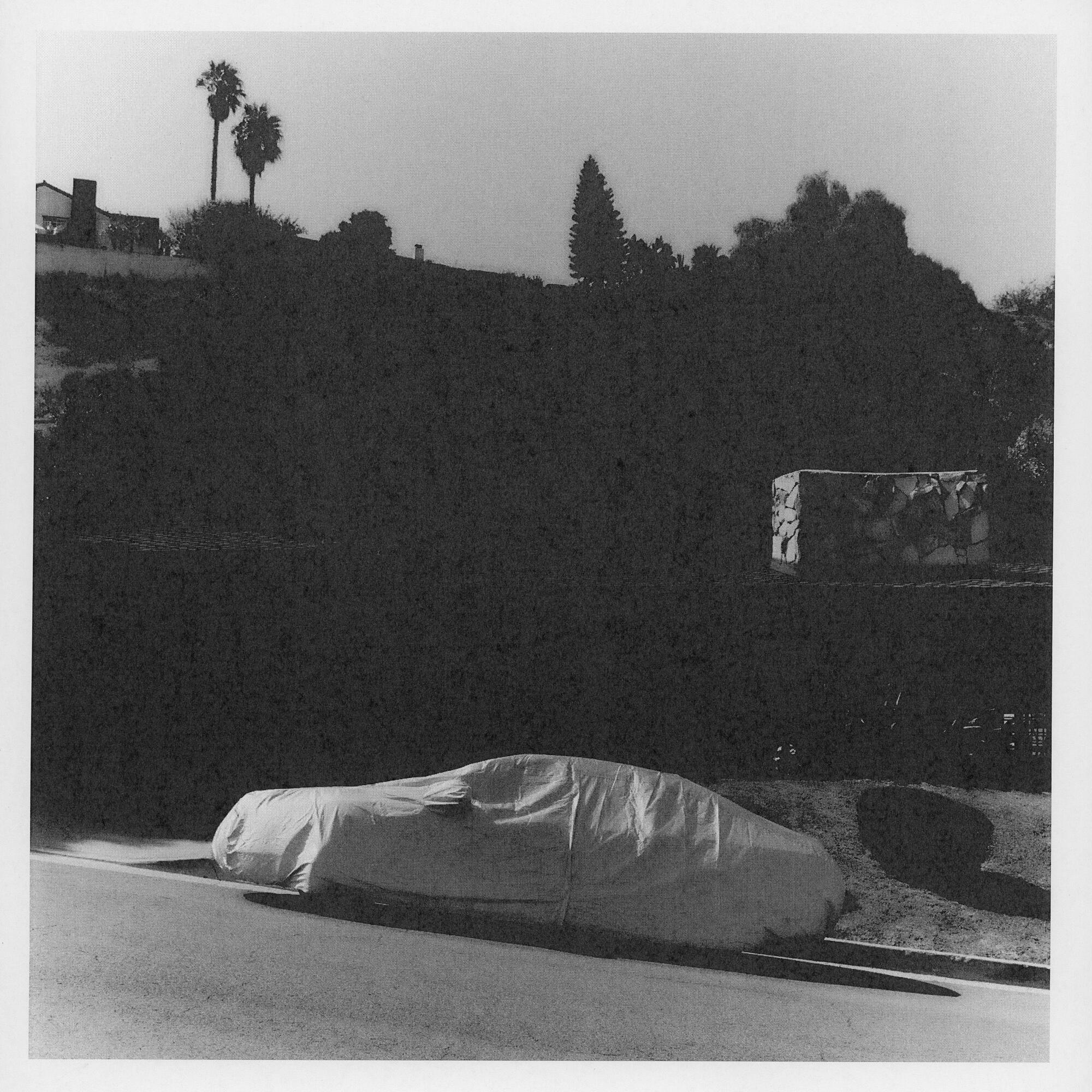

I started to look for traces of humanity, and it was really the things that were kind of covered up, like the blinds in the windows that were drawn, and then, obviously, there were a lot of cars that were covered — it takes a person to do that.

I was kind of beating myself up the first couple of days [thinking], ‘I don’t think these pictures are very good.’ I realized, once I created the dialogue for me to allow the pictures to be good in my head, then I started to see it. I don’t know if that makes sense — it’s sort of like, step out of the way what you think ‘good’ is and let something strike you. Any time I felt my head turn, I just stopped the car, got out, took the picture and didn’t ask a question. I would just do it. I think about how the process works for developing film where the silvers are being washed away by these chemicals — you’re sort of washing away your subconscious and seeing, ‘OK, these are the things that I was looking at.’

The groundbreaking ballerina who’s spent decades making history at the prestigious American Ballet Theatre is showing why institutional knowledge is a forever practice.

EWA: When you let your mind get out of the way and be taken by the moment, what was the emotion? Did you find a certain warmth in the moment where you felt this trace of humanity?

PY: It was more something eerie that stopped me. It’s like entering a room when somebody just left, and you can still feel them there but they’re absent. I think the thing that connects it all is that there’s something weird going on — I was thinking about it being a simulation, like I found the glitch, ‘Oh, s—, we forgot to draw all the people.’ Everything else is there, but there’s nobody.

EWA: You were in all kinds of neighborhoods throughout L.A., right?

PY: When I set out to do the project, I really wanted to meticulously document the cross street or I’m in Los Feliz, or wherever it was. But as I went along, I was more interested in the anonymity of the neighborhoods and how they could’ve been anywhere in L.A.

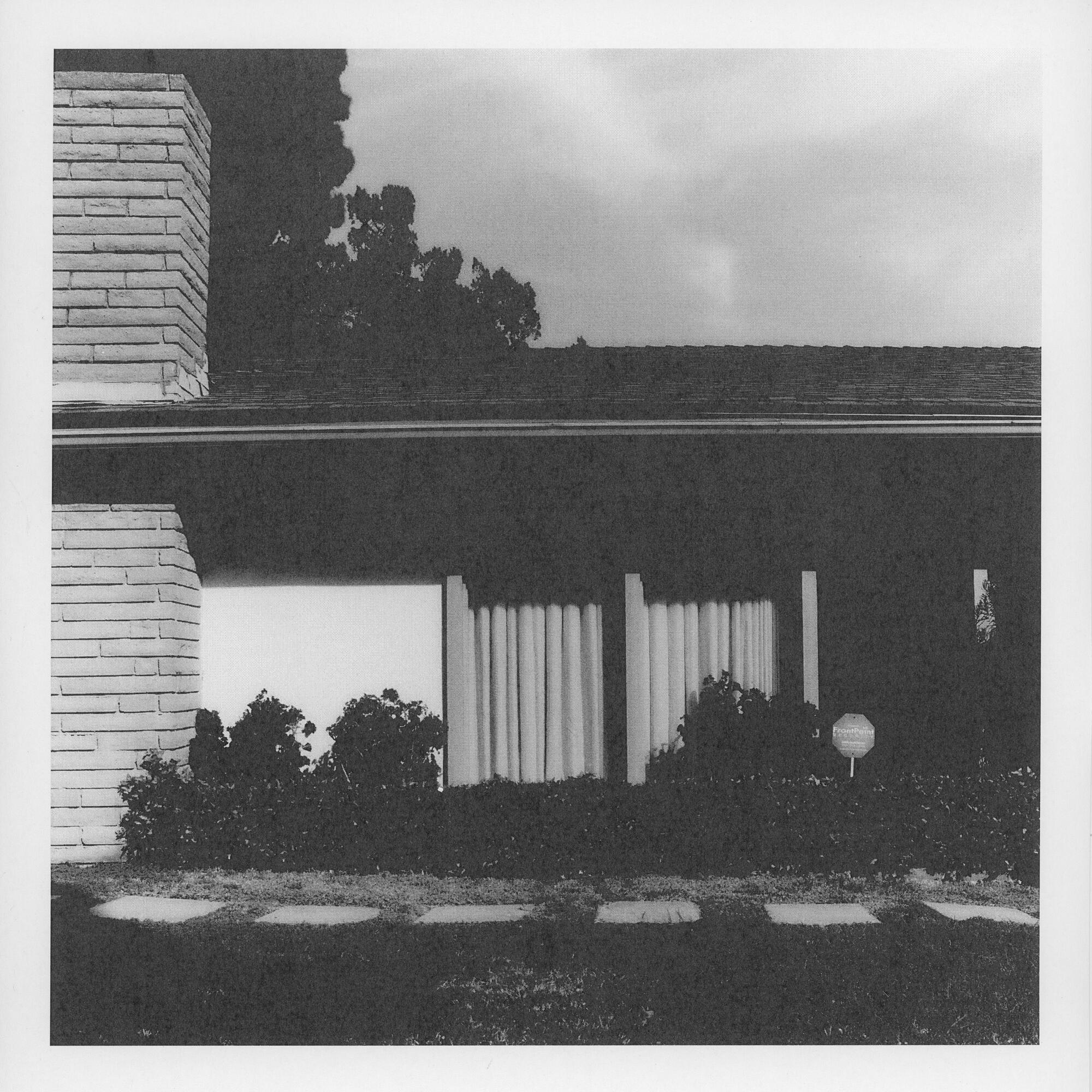

I think the neighborhoods I felt most attracted to were in the socioeconomic range of the upper middle class. I started to really unpack that in my mind — lower income communities feel more connected to me. I think it’s hard to be low income, so it brings a community together; a lot of people in that bracket spend time outside together. [With] the upper middle class, you’re entering this ability to afford privacy in a way that starts to fracture you from the community. The people who are really rich, they’re just too far gone — we can’t connect with them at all. The thing that I noticed is the more I got into these neighborhoods, and the less people I saw, the more security systems were present. It’s like the people started to gain something that they felt they could lose [and] they started to board up the houses and become more isolated [out of] this fear. The irony is there’s nobody here to steal your things.

An insufficient tribute to the ordinary people who create extraordinary works of art every single day in a city obsessed with beauty.

EWA: You named Robert Adams as an influence for you in this project. It’s interesting to think of this series as being part of a longer tradition of photography of suburbia and the American West. Can you talk about this influence?

PY: [There’s this] Robert Adams photograph of a woman. She’s in the kitchen and she’s silhouetted and it’s the perfect metaphor of this suburban loneliness or this American dream. When I think of the American dream, there’s this perfect home: the wife and the kids, the one boy and one girl and the dog, and the station wagon in the parking lot. Robert Adams takes that photograph and it’s the loneliest picture I’ve ever seen. That is what really stuck with me — the idea of that manufactured happiness, of suburbia: Let me take all the puzzle pieces that, if I put them together, will create happiness.

On the surface, it looks really beautiful. There were so many houses [that were] painted really lovely, and the landscaping is perfect. The grass is exactly three inches and I imagined them going through with a ruler. [But] I look at the space and it feels so lonely to me. In the same way I was talking about stepping out of my own way to allow these photographs to reveal themselves to me, I think happiness is that as well. It’s like happiness is this naturally occurring resource, and the more we try and get it, the further away it goes.

EWA: L.A., of all places, really has this reputation of selling the American dream, being sunny, spacious and beautiful, where anything is possible. For a long time, the single-family home was the image of that dream. You think of 20th century modernism, you have all these photographers in L.A. photographing these homes as the ideal home. When I look at your photos, there’s still this element of dream in them, but not in an aspirational way. It’s like you’re capturing the unsettling, fabricated quality of the dream.

‘No matter what I’m doing, you’ll always know where I’m from, my influences and my culture.’

PY: I love the light in L.A. The golden hour seems to hang extra long — there’s that “I want to go to L.A. and be an actor,” and that light really speaks to that. I want[ed] to photograph in the brightest, most washed out light, when the sun is at its highest point. I felt like it would make the beauty be almost sterilized in this sort of clinical way, like exactly how you posed that.

EWA: Let’s talk about your aesthetic choices. You have these very saturated pinkish colors. Then you have the black and white, almost archival approach. Some photos look ripped or wrinkled. Others look pixelated, like they’re glitching. Some look like paintings, like they’re not real. It’s a lot of different aesthetic choices that I think cohesively come together. I’m curious about your process and choices here.

PY: When I got back to New York, Ed Ruscha was having a retrospective at MoMA. His work is so graphic and vibrant and beautiful. I’m looking at the work and I’m reading about it, and I was thinking: He’s just f— around, these are all experiments, but he paints in such a meticulous, perfect way. I was compiling the layout of these images and I was excited that I saw that work at that time because I was thinking about this meticulous perfection.

I think part of that eerie feeling is perfection. There’s a hyperreality to it, where you’re like, ‘it’s not really that — he must have Photoshopped that. It can’t be that way.’ That’s how I wanted it to feel. I [scanned] the film more saturated, to play up that idea of this hyperreality. I wanted to show them as paint swatches. I imagined going to Home Depot and being like, ‘the living room is this color, it’s going to make me feel calm.’ And I was taking that one step further: the grass is this right shade of green, and if the shingles are this right shade of pink, the flowers will match. It’s that idea [that] if I can control every element and detail in my life, then I’ll be happy.

Some of the images I laser printed at a Kinkos and when you scan those, you lose a lot of quality. I was thinking of photocopying and mass producing — maybe these little houses are mass producing and you lose intimacy or a uniqueness. I was thinking of repetition of shapes and how a medium can mimic what I was thinking in my mind.

I just love black and white, and I was really thinking of the Robert Adams photograph. The second I scanned them in, [they looked] like found photographs. That felt really exciting to me because a lot of the architecture that I was attracted to graphically felt vintage or Midcentury Modern. It felt of a different time. The black and white [prints] really linked this idea of memory and nostalgia. The eerie thing that these color photographs are missing, that the spaces are missing, is this idea of nostalgia, of childhood and creating memories.

It takes a deep kind of attention to the moment to create a memory that will then later turn into a nostalgia. I imagined there being a dialogue between these found photographs and these hyperreal color ones. In the color photograph, there will be no memory of this — there’s not a smell that will draw you back to this house because it’s so contrived and eerily put together out of these swatches we found at Home Depot. There’s nothing to me that feels unique to identity. There’s some kind of loss and that is the heartbreak of the whole series.

EWA: It sounds like the black and white photos almost serve as a foil to the color photographs.

PY: That’s a great way to put it. I like referencing them as a foil because for me, this is evidence of what we’ve lost.

EWA: At the same time, I also sense that you’re trying to soften the colorful, sterile spaces — there’s some tenderness in these photos. I’m thinking of the blurry photo with the flowers by the pink house. I do find these little openings in the photos, and I don’t know if you found yourself trying to feel differently toward the houses, to get to know them.

PY: I’m glad that you point this out because — this is probably an overshare — but as I was making this work, I was sort of dating somebody, and I was really trying to get to know this person and connect with them. I just felt this invulnerability in the way they were interacting, and that kept coming into this work. I think what I’m searching for out of life is truth and vulnerability. That’s how you get intimacy. I come into the world with this sort of open, bleeding heart — I expose myself because I’m a romantic. So I was coming in looking [at these houses], thinking of who lives here. I think we all want the same thing. We all want to be happy. Some of us just have really bad tools in trying to get that. But I found myself charmed by the attempts of beauty. Since I’m not from L.A., I’m seeing these things with almost childlike vision, and I’m able to kind of see it for what it is, and I think my heart breaks a bit when I see you trying to get the same thing that I’m trying to get, which is happiness.