This story is part of “Discourse,” a fresh look at the dire state of the bicoastal conversation — free from corniness and cliches. Check out the whole issue — the “New York” issue, if you’re reading between the lines — here.

It’s often said that it takes a village. And while the old proverb speaks of raising children, I’d argue the same collective effort is required to build a career.

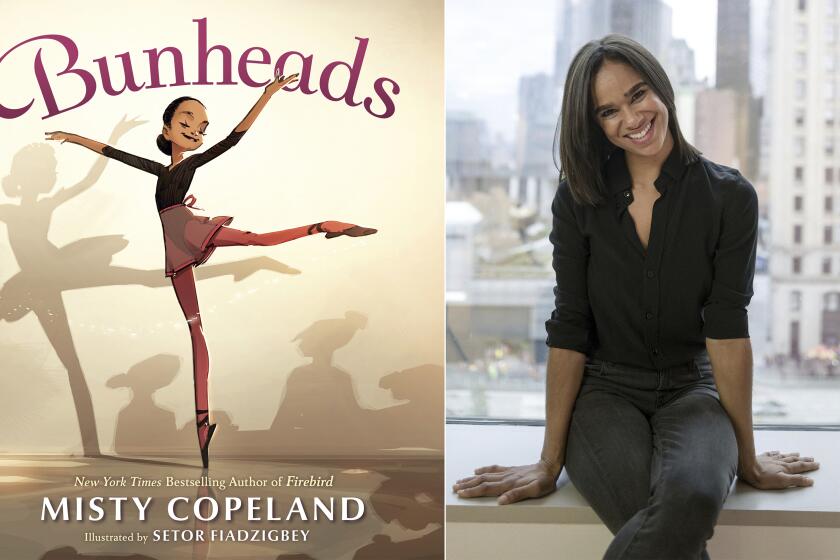

Misty Copeland, the groundbreaking ballerina who’s spent decades making history at the prestigious American Ballet Theatre, is quick to acknowledge the impact of her own “village” — a community of Black women and fellow dancers in her hometown of San Pedro, Calif., and in New York, where she’s lived and worked since 2000. From Victoria Rowell, the actress and former ballerina, to TV producer Susan Fales-Hill, to the late dancer Raven Wilkinson, such women became crucial anchors as Copeland navigated the grueling pace of classical ballet, as well as its regressive race and gender politics. And in the years since being promoted to principal in 2015 — the first Black woman to do so in ABT’s 84-year history — Copeland has focused on looking forward and backward. Her recent book, “The Wind at My Back,” is the latest in a string of titles she’s authored to celebrate the long legacy of undersung Black dancers, including her mentor Wilkinson, who in 1955 became one of the first African American ballerinas to sign with a major company, the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo.

Dance gives your whole body the chance to speak. Fashion unlocks. To celebrate LADP’s “Dance Reflections,” Sister Kokoro styled eight of the performers in L.A. brands. The result? Well...a very L.A. affair.

These days, Copeland is focused on paying it forward. Since 2021, she’s built a network of after-school dance programs for under-resourced students through the Misty Copeland Foundation and recently founded Life in Motion Productions, a film production company, with her old friend from ABT, Leyla Fayyaz. With their debut short film “Flower,” the pair pays tribute to Black and brown communities in Oakland, crafting a moving meditation on housing precarity through dance.

On a sticky summer afternoon in New York, I sat down with Copeland over Zoom to discuss “Flower,” performing for film versus the stage and finding respite in the methodic rhythms of ballet.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Dessane Lopez Cassell: You took your first ballet class at a Boys & Girls Club in L.A. when you were 13, which I know is considered late for your field. Can you tell me about that first class and 13-year-old Misty?

Misty Copeland: My mom had recently gotten her fourth divorce, and we had settled in San Pedro, Calif., which I consider my home — that’s where I spent the most time in my childhood and where I feel like I established a sense of community. I was still attending the Boys & Girls Club, which was such a safe haven for me and my five siblings. But we had moved out of my stepfather’s home, and we were kind of in between living in people’s homes. At exactly 13, we were living in a motel, and that was when I was introduced to ballet.

I grew up watching my mom — she would always dance around the house, she would choreograph stuff for us, like talent shows, because she danced growing up, nothing serious, but she went on to become a professional cheerleader for the Kansas City Chiefs. And then, my older sister was on the drill team at our middle school and high school. That was kind of what I saw, and I was like, that’s what I want to do. At 13, I was captain of the drill team for my middle school, which was a huge deal because I was so introverted, so shy. I was very comfortable dancing to pop music and hip-hop and soul, so when I was introduced to this ballet class, it was so far from anything I’d ever seen or experienced or really had any interest in. I’d never heard classical music before then. I’d never really been in a real structured environment.

But I think that I wasn’t quite ready for it at the Boys & Girls Club, because I still felt like an outsider. I didn’t have the proper attire, it wasn’t an actual ballet studio, there were no mirrors. It was a strange environment — I think of ballet as this very intimate thing; when you’re in the studio, it’s this very sacred space. When you’re in a basketball gym, it’s just not that. So I took a couple of classes there at the gym, and my teacher [Cindy Bradley] really push[ed] me, before she would take me into her school on a full scholarship and I would really experience what an actual traditional ballet class looks like.

Dancer Misty Copeland has a new book out for children, ‘Bunheads,’ the story of a young Copeland in her first ballet class and first dance production — the classic ballet ‘Coppelia.’

DLC: You talked about how you used to be the kind of kid that was more comfortable blending into the background. Could you describe your process of growing comfortable being in the spotlight?

MC: First of all, just being one of six children, and everyone having such big personalities — I kind of got lost in all of that. My nickname became “mouse.” The environment I grew up in didn’t nurture my voice. And going through school, I never felt like I fit in, like I was really good at anything. I was just surviving. There was also not wanting people to know what was going on in my home environment. There was a lot of abuse. I kept everything to myself because I didn’t want people to find out these things.

That changed when I was in an environment where I felt seen and heard. I felt like I was being nurtured, like someone had untapped something that I was good at. I felt safe; there was consistency and stability — in a ballet class, the way that it’s structured, every day, you come back and you do the same thing. There’s something that’s so ritualistic about it, and grounding. Getting up on a stage for the first time was even more mind-blowing. You’re really exposed — all of these people watching you perform. But in a traditional ballet theater setting, you can’t see the audience, so I still felt like I was in this very protected bubble. I was expressing myself through my body, which I was most comfortable doing rather than speaking.

DLC: You just wrote a book about Raven Wilkinson and her influence on you as your mentor. Are there other Black women in dance that you’d like to see more people celebrating, whether contemporary figures or folks that you’ve looked back at historically?

MC: There are so many that I feel haven’t even been touched upon. Someone that I think is important is Anne Benna Sims. She was a ballerina with the American Ballet Theatre in the ’80s. Even to this day, you can try Googling her and there’s so little. That’s someone who’s important to American dance history, American ballet history, not just as a Black woman, but she was an incredible dancer. She was a muse of Mikhail Baryshnikov when he took over the company as artistic director. She’s an important figure for people to know.

Having experienced the most spiritual growth of his life in the last year, the songbird from San Pedro is finally ready to fully share himself — and his first album in six years — with the world.

DLC: What are some of the resources that you have found over your years of learning about the history of Black ballerinas? Are there other resources aside from your own very thorough writing that you would point up-and-coming young dancers toward to learn their history?

MC: There’s a lot of stuff on YouTube for this generation. There’s also a website [by] Theresa Ruth Howard — she has a page called MoBBallet. It’s literally a list of every Black dancer, throughout history, that has been a part of ballet. It’s pretty incredible that people are really putting in the effort and the work to document our history.

DLC: Let’s talk about “Flower.” This is your second time at the helm of a film as a producer. I know you worked with your old friend and fellow dancer from your early ABT days, Leyla Fayyaz. How did you two first start dreaming up this project?

MC: Leyla and I came together in a professional sense, again, about six years ago. We wanted to give the American audience a way to be able to view the arts as something that’s a normal experience. People go to the theater in Europe like they go to the movies. We wanted to be able to show that there’s a way to tell stories that are relevant to communities today, to different cultures. That was kind of at the base of building our production company, Life in Motion Productions — the mission of it, to tell stories of the past, present and future of people of color.

All of that to say, Nelson George [director of “A Ballerina’s Tale,” a documentary about Copeland’s life and career] was the one that had been pushing me and he was like, “We need to see you on film. How can we get you acting?” That was not something I was ever interested in, outside of acting through using my body and movement.

Nelson had a thought: “Well, why don’t we do something on film like you do on the stage, which is silent storytelling?” So it kind of evolved from this idea of a silent film, and Leyla and I took this idea and ran with it. We started thinking about Black silent films, race films. How do we pay homage to [them], and, again, using ballet [to] tell a story that’s relevant to today? To be able to tell this story that’s deep and heartfelt, [and] to tell that through movement without words.

DLC: You’ve been in a few film and moving image projects at this point. I’m wondering about the experience of dancing for the film versus the stage. How do you prepare or approach performance differently?

MC: It’s so hard in such different ways. We filmed “Flower” over the course of five or six days. But my time working for Disney’s “The Nutcracker and the Four Realms” was a real experience of what it is to be a part of a film as a dancer. I think it’s important that you have a team that understands and respects what it is to be a dancer — it’s not like being an actor, you can’t just come in and say, “Oh, you have 10 minutes, get up for the next scene.” You need a 30-minute preparation in order to warm your body up again. It’s really hard to just stop for hours at a time and then pick up again. [In] a live performance, [you’re] going straight through — there’s no breaking character.

[In film], you can make mistakes and have more chances and other takes to get it right, which is a nice feeling. Then there’s the acting that’s very different. When I perform at the Metropolitan Opera House, the acting can feel over the top, and it’s not the same as what you would do in front of a camera, so it was really [about] taking it down and allowing for everything that I was doing to feel more human and more grounded and more natural. But I enjoy both of them.

In the 1950s, he quickly developed a reputation for being a gun-toting, switchblade-carrying man on one hand and an impossibly tender soul who could write love songs with the facility of angels on the other.

DLC: I think something that you’re saying touches on the oft-repeated narrative about ballerinas as these perfectionists. I know this is a trait you’ve acknowledged in yourself. I’m wondering if there were any ways that making this film allowed you to perhaps get comfortable with not being the expert or not having all of the answers all the time?

MC: Absolutely, because this was not something I’d ever done before, so I kind of had to let that go. You want to be as prepared as possible, but there are some things that are just out of your control and you have to trust [people’s] experience. I remember one scene in particular — I wasn’t using movement in any way, I was just doing day-to-day things, and having to show the emotion of what I was feeling for my mother [played by Christina Johnson]. I remember Nelson George being on set and having conversations with me about his own experience with his mother and how he felt — just drawing from a real human experience of someone who’s experienced something similar, that was really helpful. Again, just being open enough to trusting other people who have done this before.

DLC: I have to ask, as someone who was a big “Center Stage” fan as a kid, what are some of your favorite, more contemporary dance films?

MC: [Also] ”Center Stage,” I grew up on it and loved it. I enjoyed “Black Swan,” getting into the psyche of an artist. But my faves are “The Red Shoes” and “The Turning Point.”

DLC: What else can we look forward to from you as a producer?

MC: There are a ton of projects in the works. We’re excited that “Flower” happened to be the first one to come out. That wasn’t the plan. But I feel like it really represents who we are, as of right now, as a production company. I think we’ve created our own lane in this form of storytelling. We’re really focused on this concept [of dance films], and so we really want to take “Flower” and make it into a series so that we’re telling different social issues and using different styles of dance . We’re diving into the animated world, the documentary world, big Hollywood films, telling stories of people that we don’t know enough about, women of color — we would love to be able to tell their stories in a way that really speaks to who these people were as artists.

Styling assistant: Elle Walborsky

Makeup: Victor Henao

Hair: Jeff Francis

Location: Jack Studios

Dessane Lopez Cassell is a New York-based editor, writer and curator. She gravitates towards film and visual art concerned with race, gender, decoloniality and the politics of paradise.