This story is part of Image’s August issue, Lineage, about intergenerational conversations and how they shape us.

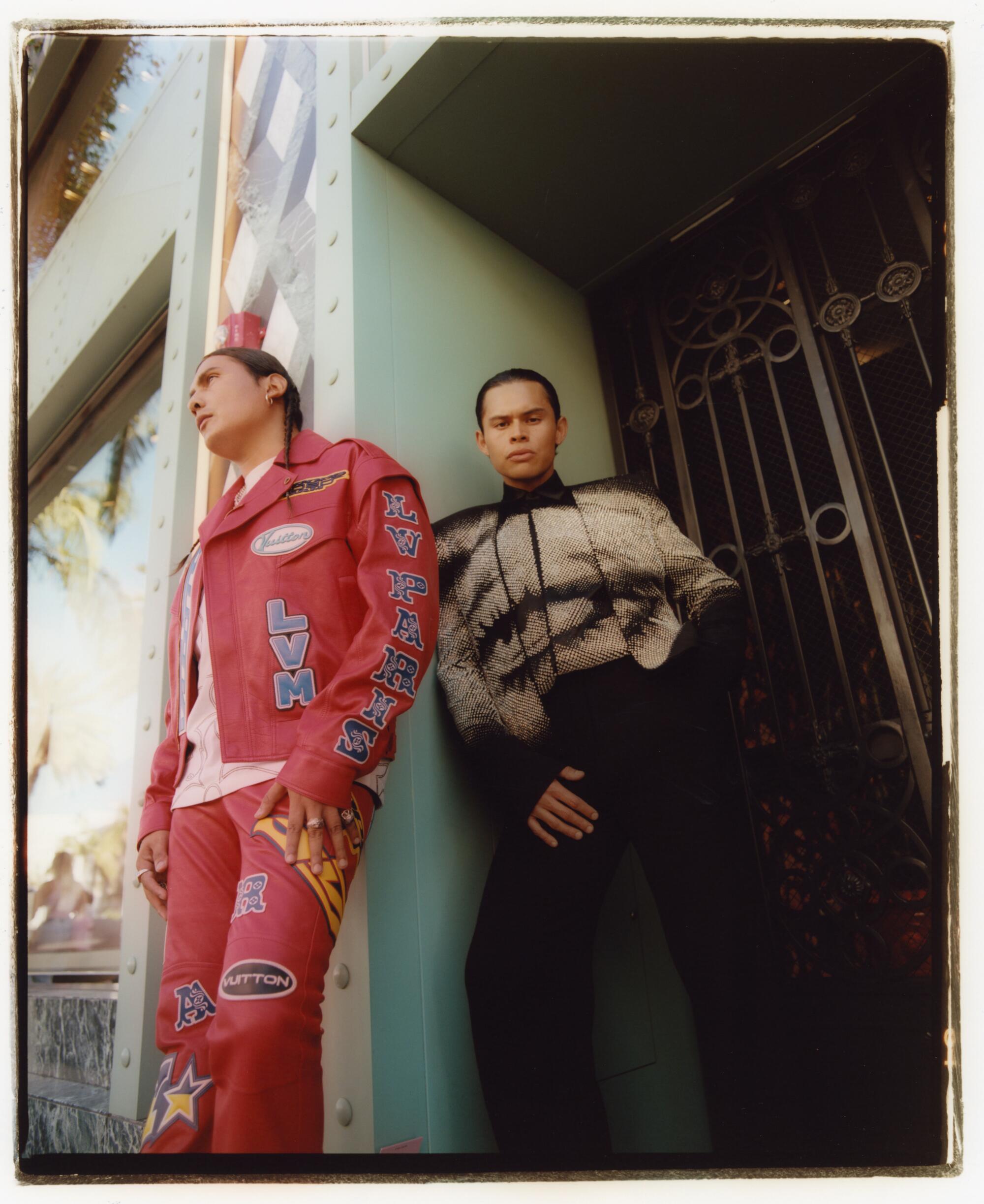

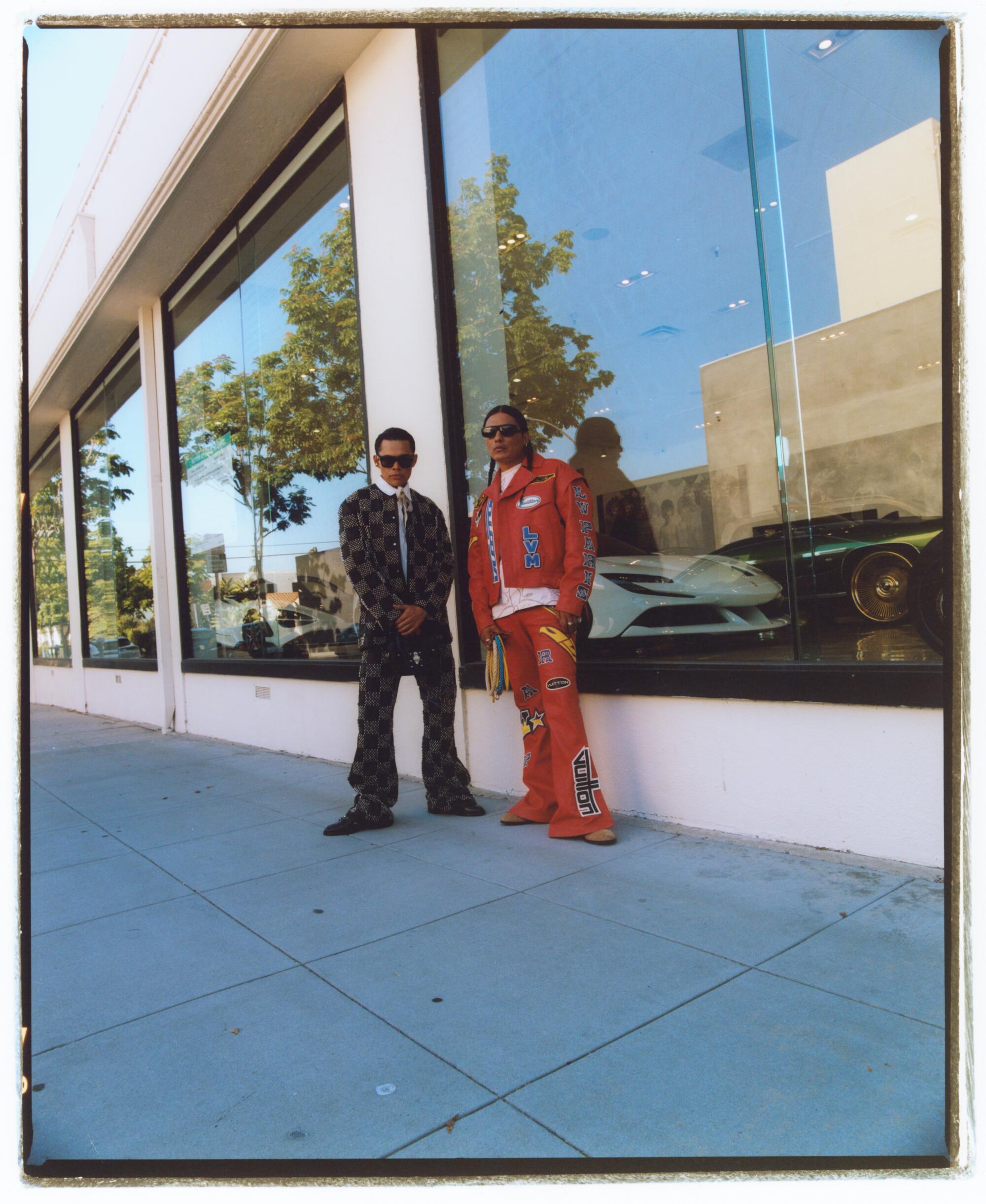

The photos are warm and grainy, some of them taken at an angle. They show four young men smiling — no, beaming. It’s 1991: The jackets are puffy, the shoes are high-top, and the hair is specific. In the photo, the men are somewhere in Beverly Hills, where, whether they realized it or not, they were manifesting a new future. Standing in front of the large glass windows of a luxury car showroom at night, butterfly doors opening up like angel wings in the background, the men in the photos feel like they’re on the precipice of something special. They’re fronting, they’re flexing, they’re bonding.

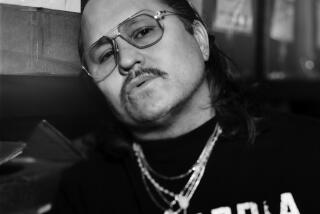

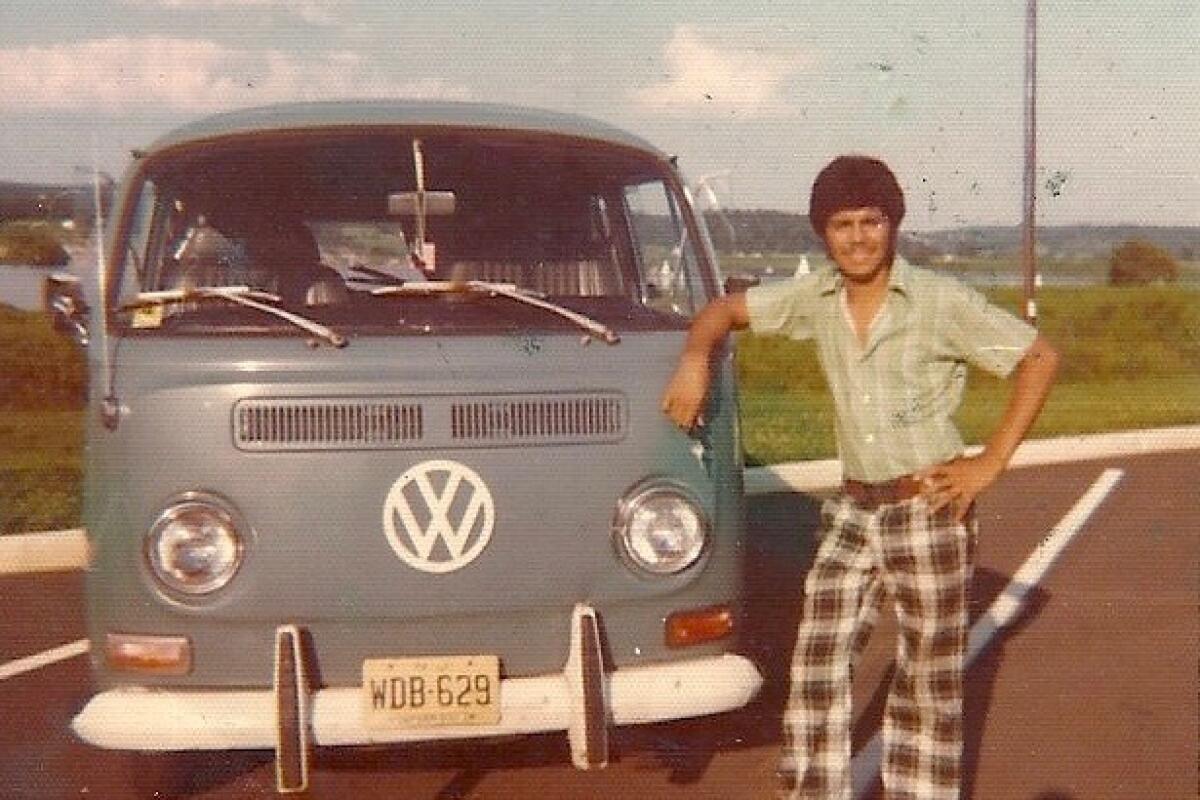

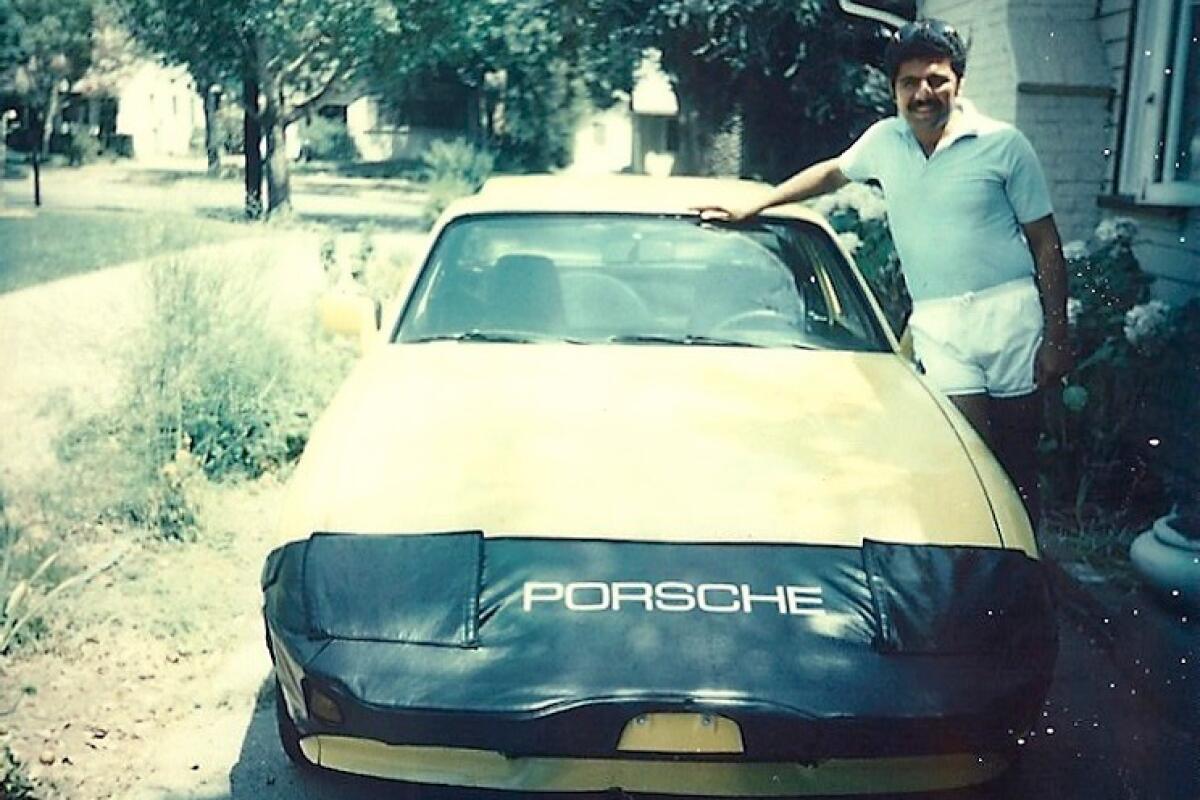

The people in the images are the elders of Image’s fashion director at large, Keyla Marquez, captured at time when they’d recently immigrated to L.A. from El Salvador. This was their ritual: After endless days working at restaurants, Marquez’s uncles, father and family friend would book it to Beverly Hills, where they’d post up in front of fancy car dealerships that sold Ferraris, Porsches and Rolls-Royces, and have photo shoots. In the moment, it was something to do, a reason to get out of the two-bedroom apartment they shared with three families, a way to take up space in this new city. It’s a photographic tradition that was familiar to photographer Thalía Gochez, whose own father came to the U.S. from El Salvador as a young teenager and also used to take pictures of himself in front of classic cars around L.A., inscribed with love notes to her mother on the back. For both sets of families, these photos were hard proof: that they were here, that they had made it.

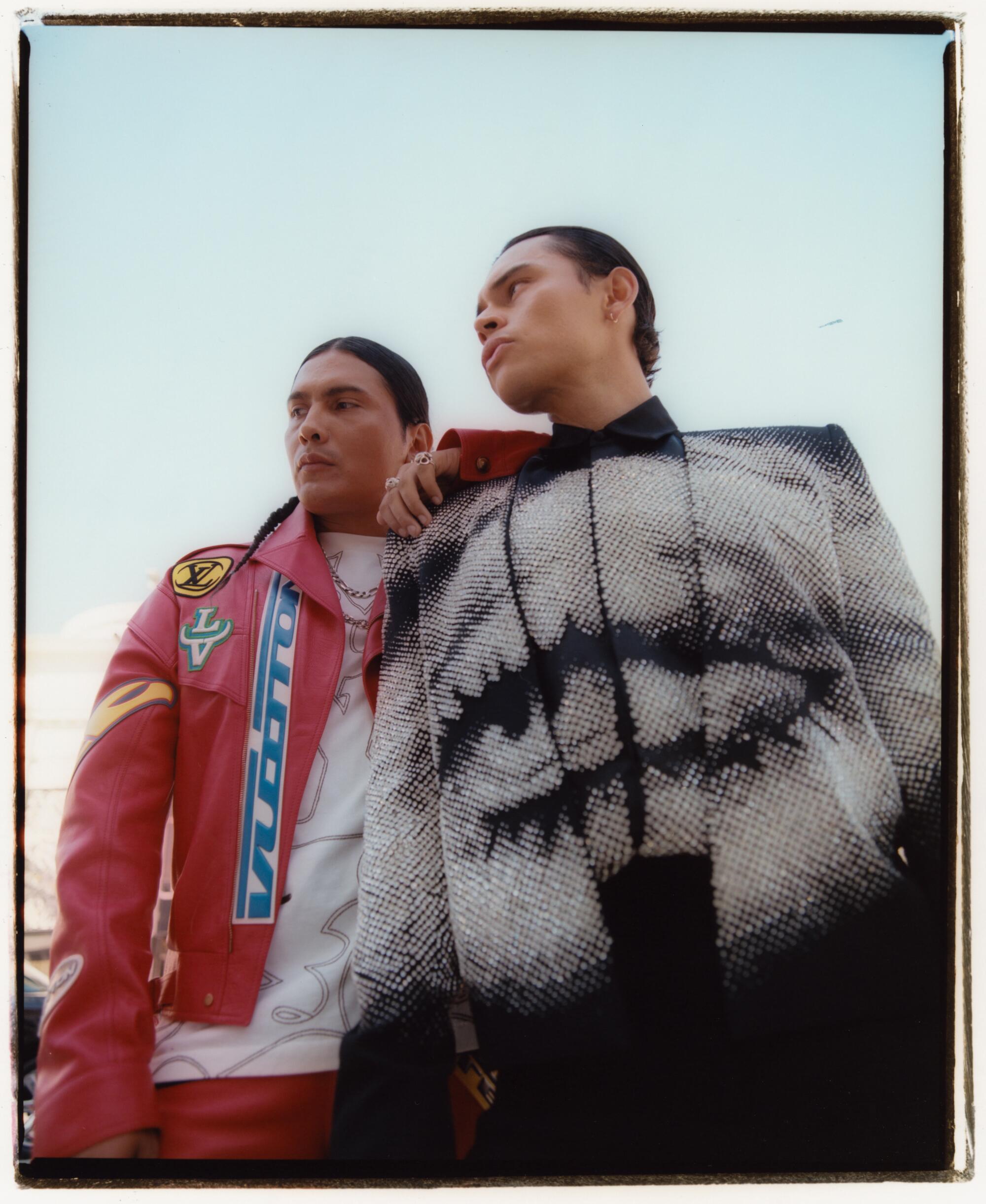

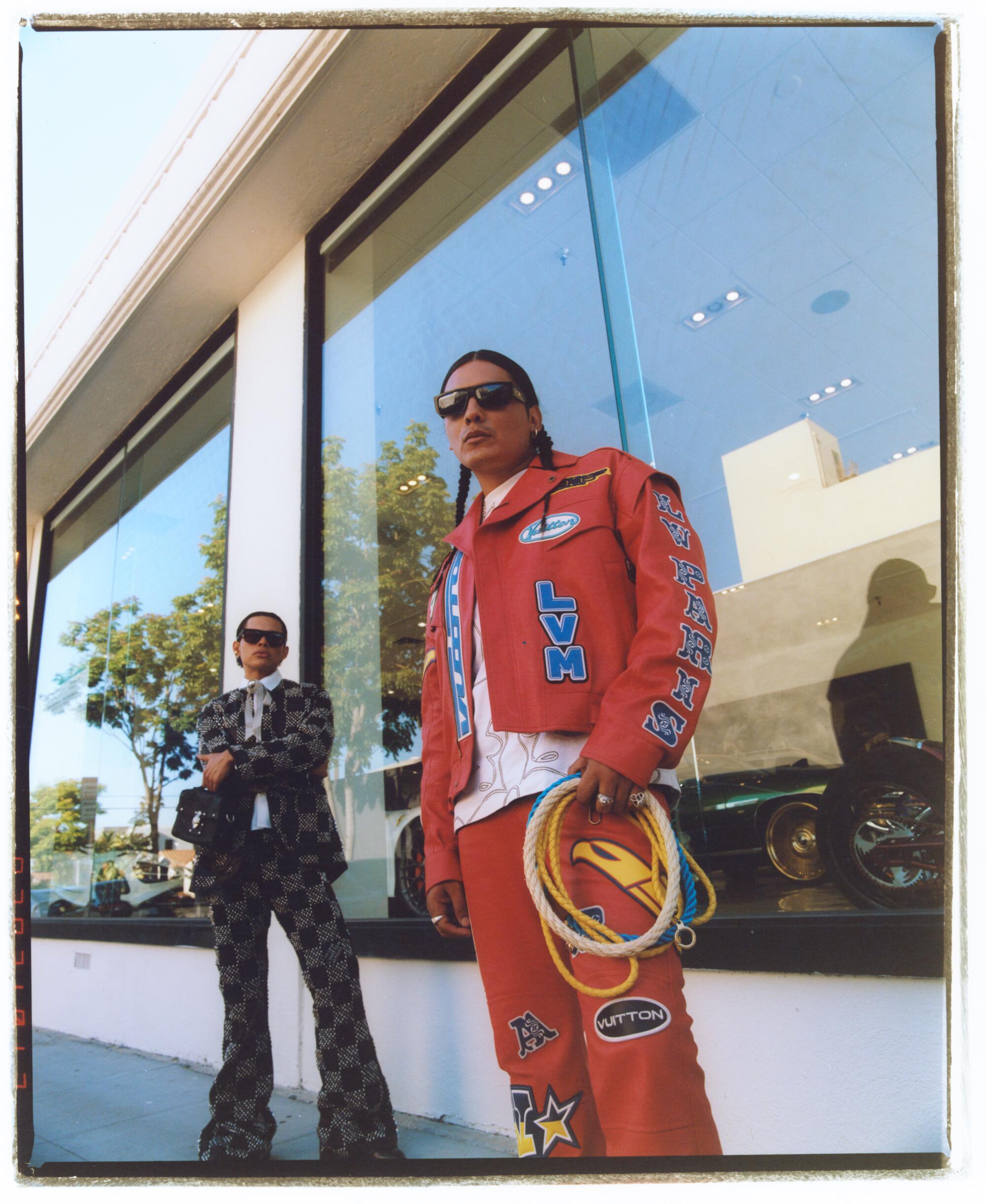

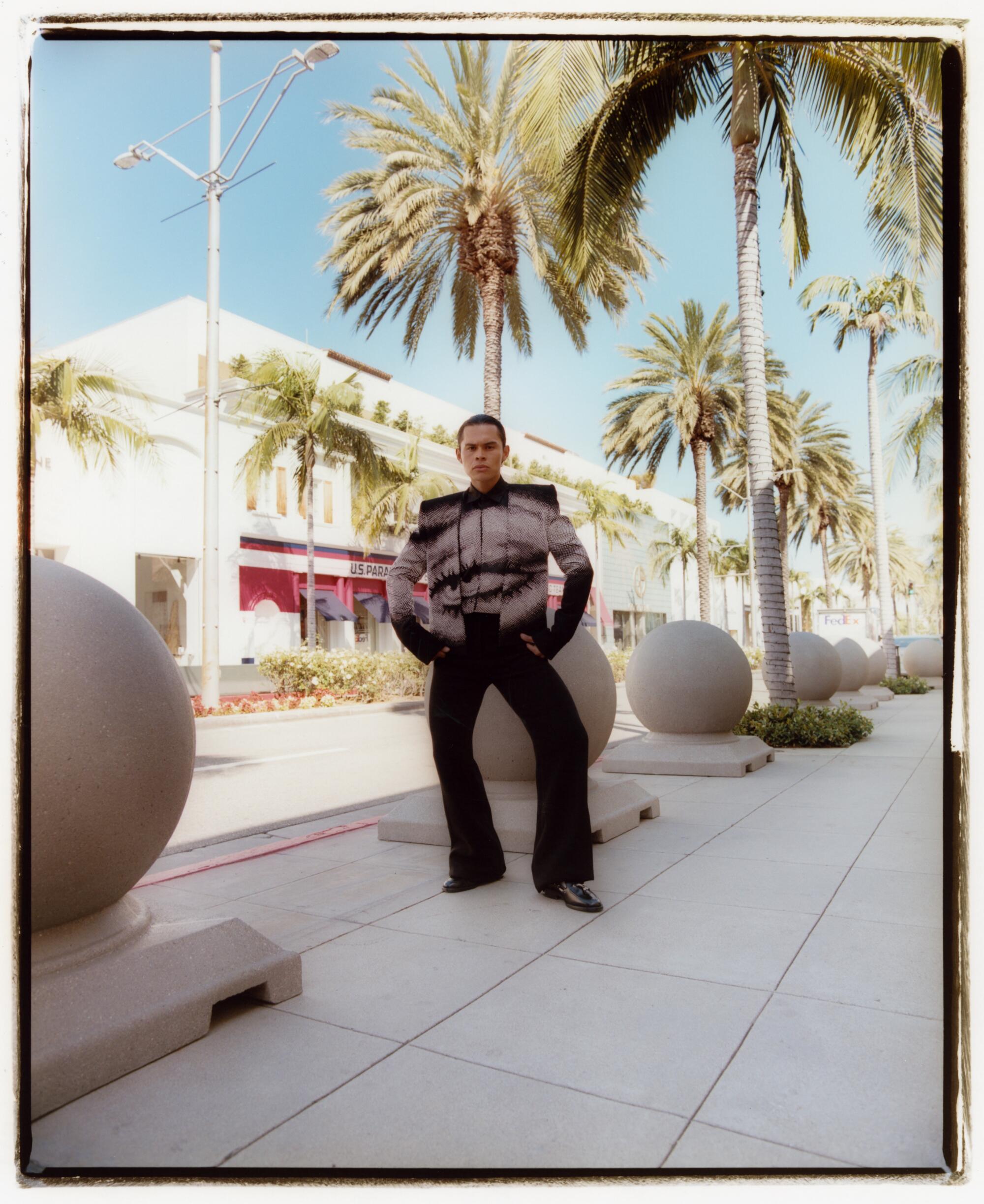

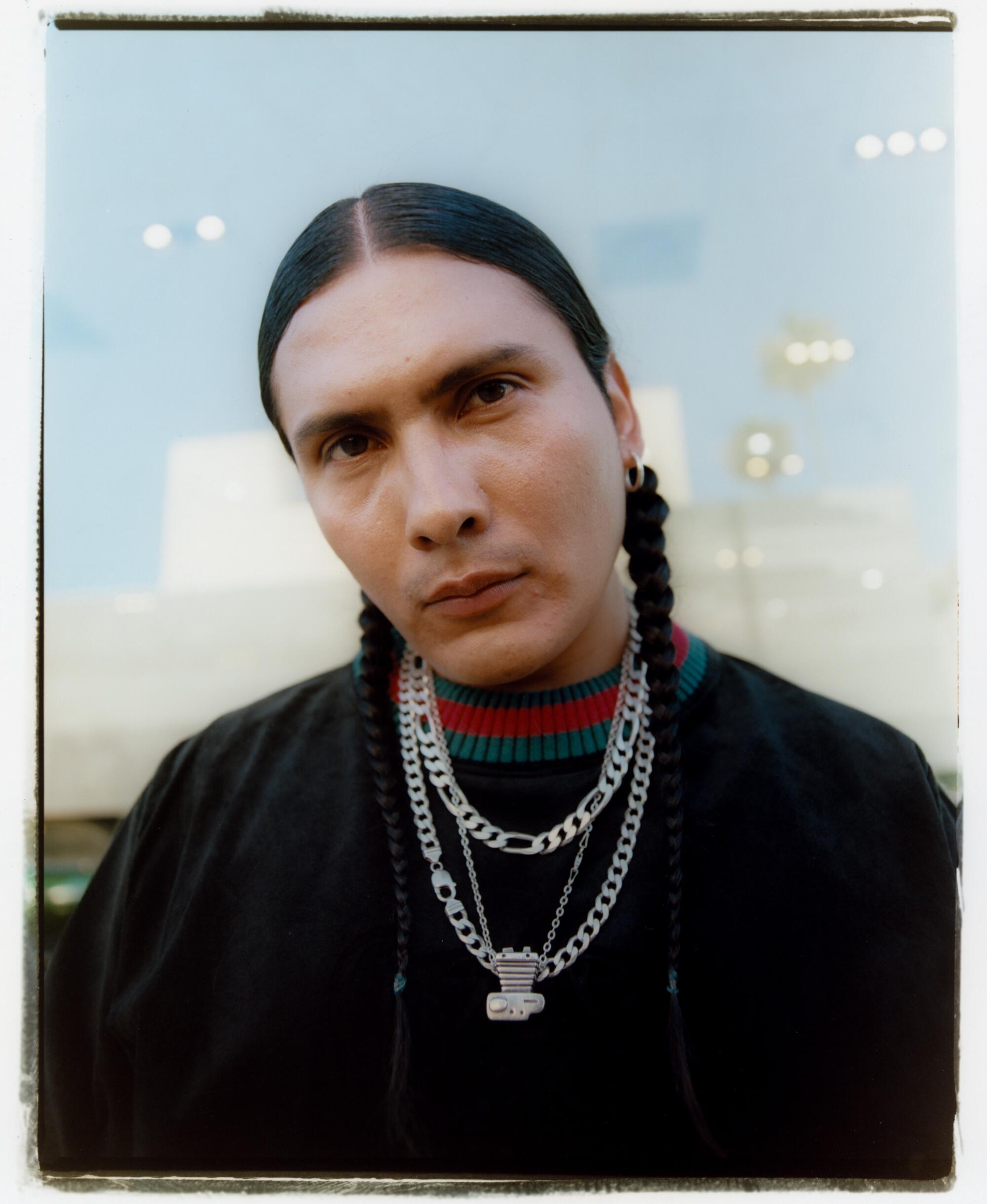

This editorial is Marquez and Gochez’s re-creation of these relics left behind by the men in their family. It was brought to life with two of Marquez’s closest friends as models, whom she describes as her “babies”: artist and founder of Tlaloc Studios Ozzie Juarez, and film director-model-multidisciplinary artist Pablo Simental. The energy at the photo shoot was nothing short of familial, with Marquez, Gochez, Juarez and Simental all understanding the vision through a sort of shorthand. With the project, Marquez and Gochez honor this ritual as an art form, and cement it as a Latino immigrant tradition.

NASCAR tapped the artist to make a trophy for the inaugural NASCAR Mexico Series race at the L.A. Memorial Coliseum this Sunday.

Keyla Marquez: My mom has photos laying everywhere. I opened a shoebox and on the top was [a] photo of my uncle. I was like, “¿Mami, qué es esto?” She was like, “Your dad and your uncles — because they used to all work at restaurants — after they would get done with work, on the weekends, they would go and cruise Beverly Hills and take photos in front of cars.” They would send those photos back to El Salvador and be like, “Look, this is what life in America is.” I [thought] it would be cool to do something inspired by this.

For this story, I really wanted to work with Thalía. ... So much of her work is Latino, brown stories. I reached out to her and gave her the whole spiel via DM. I sent her a photo of my uncle. And then [Thalía] responded, and [was] like, “Yo, my dad used to do the exact same thing.” And then she shared a photo of her dad and was like, “My dad used to take photos in front of cars, and none of them were his and he would write things in the back of the photos, too.” Our families are so cute. Here we are, just fronting. It was meant to be.

Thalía Gochez: I’ve always been a fan of Keyla’s work. And we both followed each other for a minute. When she DMd me, I was like, “Let me open this right away.” I was super excited when I heard the actual concept. A big part of my artistic practice is honoring lineage and honoring story through style. It’s always been important for me to go beyond fashion to create a story and highlight identity. This [project] is so aligned with what I always want to do and what I already do. Also a big inspiration for me not only is my culture and heritage, but my childhood and my upbringing. I’m constantly looking through archives, through family photographs.

My dad passed away when I was 15. He was a huge car guy. That’s how he put food on the table. He would sell really rare Porsche parts — we always had classic cars in the driveway. He was a one-man show. But before I was born, he would take a lot of photographs in front of cool cars, and it’s exactly what Keyla said, he would write things to my family back in El Salvador. It wouldn’t just be in front of cars, it would be in front of restaurants, fountains, this idea of luxury. This is such a rare shared experience. It’s a true sense of community — that word is hyperpopularized, but this right here, what we’re doing, is community-building. That’s what’s so important about art and what photography can actually do.

Thalía Gochez’s father in Los Angeles. (Courtesy of Thalía Gochez)

KM: I think it’s a ritual that a lot of immigrant families partake in. Even when we were shooting [this editorial], a lot of tourists were literally posing to take photos in front of the Louis Vuitton store. It’s still happening, it’s just a little more polished now. For my family, [it was] putting on their Sunday’s best and just going and taking photos in front of places selling the American dream. It’s their definition of luxury. Especially Beverly Hills — in El Salvador, you think it’s so elegant and so unattainable, that’s where all the rich people live. Then you go, and it’s not what you think it is, but you still want to sell this image and this idea, and it’s like, “What are the places that we can go and take photos of?” The stores and the car dealerships. I think it’s letting people know that “look, we crossed the border, and it was all worth it, because here’s this photo.”

TG: For my father, when I look at those photographs, there’s a spiritual aspect to it. He was kind of manifesting this life. He was like, “Oh, hey, look at this car. I don’t have it yet, but stay tuned.” And a lot of the cars he did [end up having]. It’s a very hard thing to leave your home country, come into a new space, and have this access to luxury. A lot of it, too, is empowering. Like, “Look, I came all the way over here. I’m in front of this amazing building, in front of this car, and I feel empowered, I feel this is mine in some way.” Even growing up, I remember going on car rides with my dad and my family through nice neighborhoods and looking at all the houses, even in Beverly Hills. Maybe he didn’t have that access to do that in his home country. But here, it’s within reach. It feels like a part of his story.

Bibs Moreno’s project captures people in L.A. in their natural luminosity. The magazine — much like its cousin Fruits, which documented style and subculture in Tokyo — is a sensory world of aesthetic celebration.

KM: I wonder what conversations they had hanging out there taking photos. Like, who brought the camera?! Who was just like, “Nos vamos ir a tomar fotos”? You see a softness in those photos that you usually don’t see in Latino men.

TG: It’s incredibly vulnerable too because, yeah, they’re manifesting, but it’s technically not theirs.

KM: My family worked a lot when they first moved here, day and night at Chinese food restaurants. They lived in a two-bedroom apartment — it was three families. At night, it was like, “Let’s go out and drive around and have a moment outside from our apartment where we don’t even have space.” They had to go out to have a moment to bond with the other men in the family. It was mostly just not having resources and using the sidewalk as a resource to hang out.

TG: There was definitely a lack of space to explore your imagination, so they created their own little spaces. Backtrack to when [my dad] was in his 20s, he was a huge storyteller. When he was trying to pick up my mom, he would take pictures of himself and write novels about it and send it to her. When I look back at his life, and how he moved, he was very much an artist. He would take the most beautiful portraits of my mother. I also wanted to ask who took these photos of him. Would he do a timer? He was a very solo man, so I need to know more. Maybe one day I’ll have that privilege of learning that.

KM: I come from a very religious family, where people just pray for you nonstop. [Seeing these photos], it was like our prayers had been answered. Crossing a border was really hard back then, and everyone in my family did it. [It was like] all those extreme, super dangerous things were not in vain. Every time [family members from El Salvador] come here, they’re like, “Take us to all the places that you sent us photos of.” [We take] the family to the Hollywood sign, [to] Rodeo. When I first started making good money, I took my mom to the Gucci store to buy some shoes. That’s a big deal for immigrant families. Never in a million years did my mom think she would be buying something from a store on Rodeo.

It’s easy to see yourself going somewhere in these clothes, even if it’s to nowhere in particular.

TG: I feel like we’re not normally allotted that opportunity. I think [my family’s perspective] was that they thought he was just rich.

KM: They all think we’re rich. Like, “They’re millionaires in America.”

TG: Obviously, [my dad] wasn’t [rich] in our perspective, but he was earning and had access to even just clothes, food, resources that they didn’t have access to. So in their eyes, he was this success.

KM: It’s important to let the world know how much value there is in these stories. When you bring in some of these brands that are not accessible to the world — some of the looks that I got are probably not even going to get made to be sold in stores, there’s so much exclusivity in that world — for me, it’s like bridging that gap. I can bring in that world because of the agency that I have in this world. And I can bring in my community and my friends, and bring in this memory from my family. Bringing all these things together and retelling this story, that’s such a superpower. I can’t wait to see how many people are going to be like, “My family used to do that, too.” I was in the car coming home [from the shoot] and I was just crying because I’m so grateful and blessed that I get to do this. An immense feeling of gratitude and love that I get to tell these stories.

TG: For me, it was important to honor my father. Honor what he used to do. A lot of the blessings I have today in my life are because of him, because he did dream, because he did create those spaces for himself. I am reaping the benefits from his labor, from his resilience, from his tenacity, from his ambition. He came to America at 14 years old with $10 in his pocket. And now, I’m able to support myself fully financially from my art and that’s such a privilege. I wouldn’t have been able to do that if he didn’t didn’t lay down the foundation. So a big part of this project for me was just to honor him and the rituals he used to do.

KM: That’s the goal with everything that I do: the ripple effect it causes. What is it going to inspire a younger me to do? I wish I had seen someone like me growing up.

Production Mere Studios

Models Ozzie Juarez, Pablo Simental

Grooming Carla Perez

Styling Assistant Deirdre Marcial

Pinstripe Art Diana Ramirez