This story is part of Image Issue 16, “Interiority,” a living archive of L.A. culture, style and fashion that shows how the city moves from the inside. Read the whole issue here.

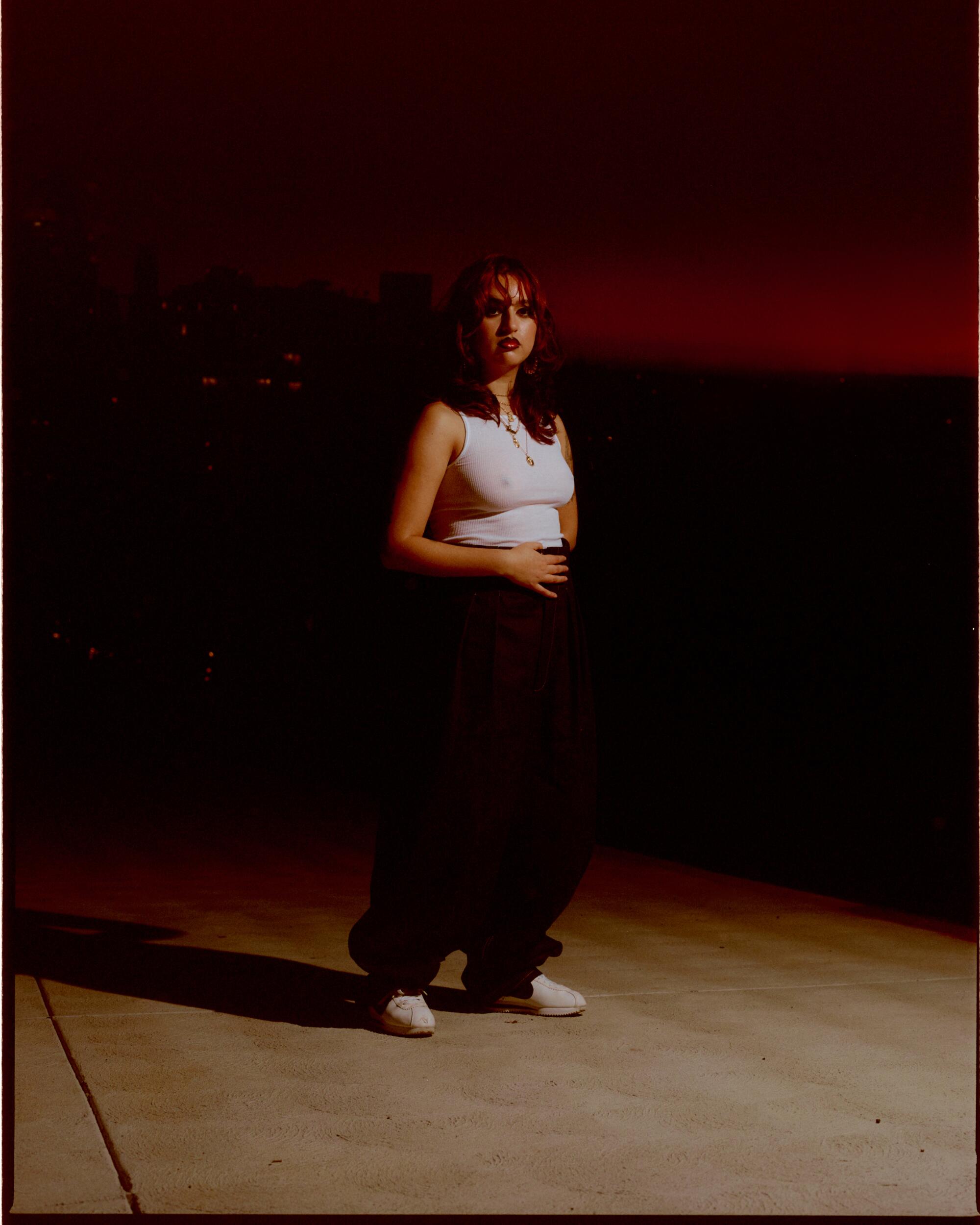

There’s something about Shorty that’s undoubtedly glamorous. She’s petite, as her name suggests, and she’s thick, thighs grazing together as one. Her hip-hugging maroon jumpsuit complements her mahogany lipstick to perfection. Her face is framed by feathered chestnut waves and carries a subtle expression that says, “Yeah. And what?” Her stance, arms crossed over her chest, knees slightly pointing into each other, looks like she’s waiting outside the club for her ride after a long night.

Shorty hangs from my keychain. She’s no more than an inch and a half tall and made of plastic. She’s a Homies figurine, a lucky find I picked up at a thrift convention over a year ago from a vendor who specialized in the resale of the collectible toys. I was drawn to Shorty because she seemed to know who she was, and she held a lowbrow elegance that I’ve tried for years to emulate. Every part of her look had been accounted for. The hair, the makeup, the stance, the expression — it all told a story about who she was and what part she played in her community. According to her bio, written by Homies founder David Gonzales, Shorty is “a hot little club babe,” a romantic who falls for men too quickly. Shorty was familiar because we’d met before.

She was there, on days spent at my uncle’s house over 15 years ago, when I gazed carefully over his displayed collection of what was at least 100 Homies. Me and my cousins could be there for hours, careful not to touch one too recklessly because then the other homies might come tumbling down. Arranged on a glass counter, each Homie standing centimeters away from the next, the display was an entire world on its own. Every figurine had a well-defined personal style that told a story about its identity. Narratives were baked into each name — or more specifically a.k.a: Flaco, Gata, Tiny, Shadow — and outfit. It was a masterclass in world building: A Homies figurine’s clothing and disposition could tell a tale about who they were or who they wanted to be — a lesson that, as a child in the early 2000s, I felt called to learn.

There’s a surprising sturdiness to Homies figurines. They feel heavy when you hold them in your palm, almost like you know each one has a tale to tell. Many have weathered more than 20 years without much deterioration. Each one of the classic characters, of which there are hundreds, is somewhere around 2 inches tall and half an inch wide. Tracing your thumb over the figurine, you can feel the grooves of a pair of Locs sitting on its face or the towering pompadour greased atop its head. The paint on most of them, in my uncle’s collection and the countless I’ve seen on eBay, has now survived decades.

But the Homies’ longevity goes far beyond the physical form.

This past September, at the Lowrider Super Show in Las Vegas, throngs of fans came to visit Gonzales’ booth, some in Homies cosplay. He debuted the toys in 1998, to tell a story about Chicano life in a fictional East L.A. barrio he called Quien Sabe, inspired by growing up in Richmond, Calif.

If you look around L.A. today, you’ll see whispers of the Homies across fashion, art and culture. Part of it is that the ’90s are in — nostalgia reigns supreme over our city, for better or worse — but the aesthetic reachback isn’t solely rooted in sentimentality. Homies articulate, in visual form, a heritage that goes deeper than that. Those same looks have been passed down to young people in L.A., and San Diego, and Denver and Albuquerque for generations — the exaggerated elegance of oversized pleated chinos that nod to the Zoot Suit era, the Y2K specialty of low-rise baggy jeans exposing a thong line, big hoop earrings. Homies had a way of capturing these things in painstaking detail. They were an exaggerated version of that look, maybe, but embellishment can be about recasting emphasis, pushing past boundaries or even abolishing the limits altogether. Homies expanded the possibilities of the style they emulated and painted a fuller picture of what the fashion archive could look like. For people who have always felt connected to these looks and the stories they’ve told, Homies serve as a style syllabus — just like the old star shots of your aunts at Tom’s One Hour Photo — for life to imitate art imitating life.

David Gonzales is the Homie King. That’s the moniker he wears on his hats and embodies in conversation as he talks about his life’s legacy. He’s an acute observer of life, culture and style in the place — Richmond — that raised him.

The characters he created first were based on himself and his friends, which he immortalized in a comic strip that Lowrider Magazine published from 1978 to 1982. In 1994, Gonzales debuted Homies merchandise that would morph into the the first iteration of Homies figurines, which surfaced in 1998: Smiley, Pelon, Bobby Loco and Hollywood. Gonzales sold them at quarter vending machines in laundromats or grocery stores, and later on the shelves. In the first four months they sold 1 million figurines.

“It was created organically,” says Gonzales. “I didn’t sit down and say, ‘I want to make a million-dollar toy product.’ I just started drawing friends. I was drawing my culture.”

Gonzales approached Homies from the perspective of a sociologist. He remembers clearly what his lowrider friends in Richmond — and later San Jose, then L.A. — wore, what they called themselves and how the combination of those things shaped their identity, gave them a sense of self that felt relatable, even if it changed slightly based on region. No matter how specific the experience of Gonzales’ actual homies, there was something genuine about how they projected their ideas of self outward through presentation. It left the door open for connection: How one person represented themselves might inspire another to follow suit. In some cases, one look could reveal similarities in taste. While everyone was distinct, Gonzales remembers a kind of uniform: T-shirts, khakis, Derby jackets, beanies, Wallabee shoes or Wino shoes. Clothing was the connective tissue.

More stories from Interiority

rafa esparza on the story of ‘Corpo RanfLA: Terra Cruiser’

Sam Muller unpacks the oral history of Hollywood High 16

Julissa James examines the style legacy of Homies

Angela Flournoy talks to Robin Coste Lewis about ‘deep time’

Alan Nakagawa remembers the Japanese market on wheels

Style has always been a visual language, one we use to communicate certain aspects of ourselves, our backgrounds, our beliefs. Goths. Rockabillys. Skaters. Punks. A person or a group can say something important about their social world and values without ever uttering a word. A look can say everything or nothing.

Many have a favorite Homie — one that reminds us of who we wanted to look like or of someone we knew. Maybe it’s Huera, with her blonde tresses, piercing blue eyes and matching oversized khaki suit. Or Old School, a noted “cool dresser” from the ’70s who had slicked-back hair, pleated pinstripe pants and an enviable vintage Charlie Brown polo. “I always found myself being drawn to the cholas, especially the ones with the long feathered hair,” says Denise Sandoval, professor of Chicano/a studies at Cal State Northridge, curator and scholar on lowrider culture and Chicano cultural histories. “It reminded me of the women that I would see growing up in La Puente in the ’80s.”

Sandoval is curator of “The Politics of Low and Slow,” an exhibition currently up at the CSUN library that features some Homies from her personal collection. In the exhibition, she writes about the ways Homies exhibited a kind of aesthetic and style that could only be born of the community. “Identity is performative — we’re performing how we express who we are,” Sandoval says. “Fashion, particularly for working-class folks, is one of the ways in which we can do that. We can use what we have to create beauty for ourselves.”

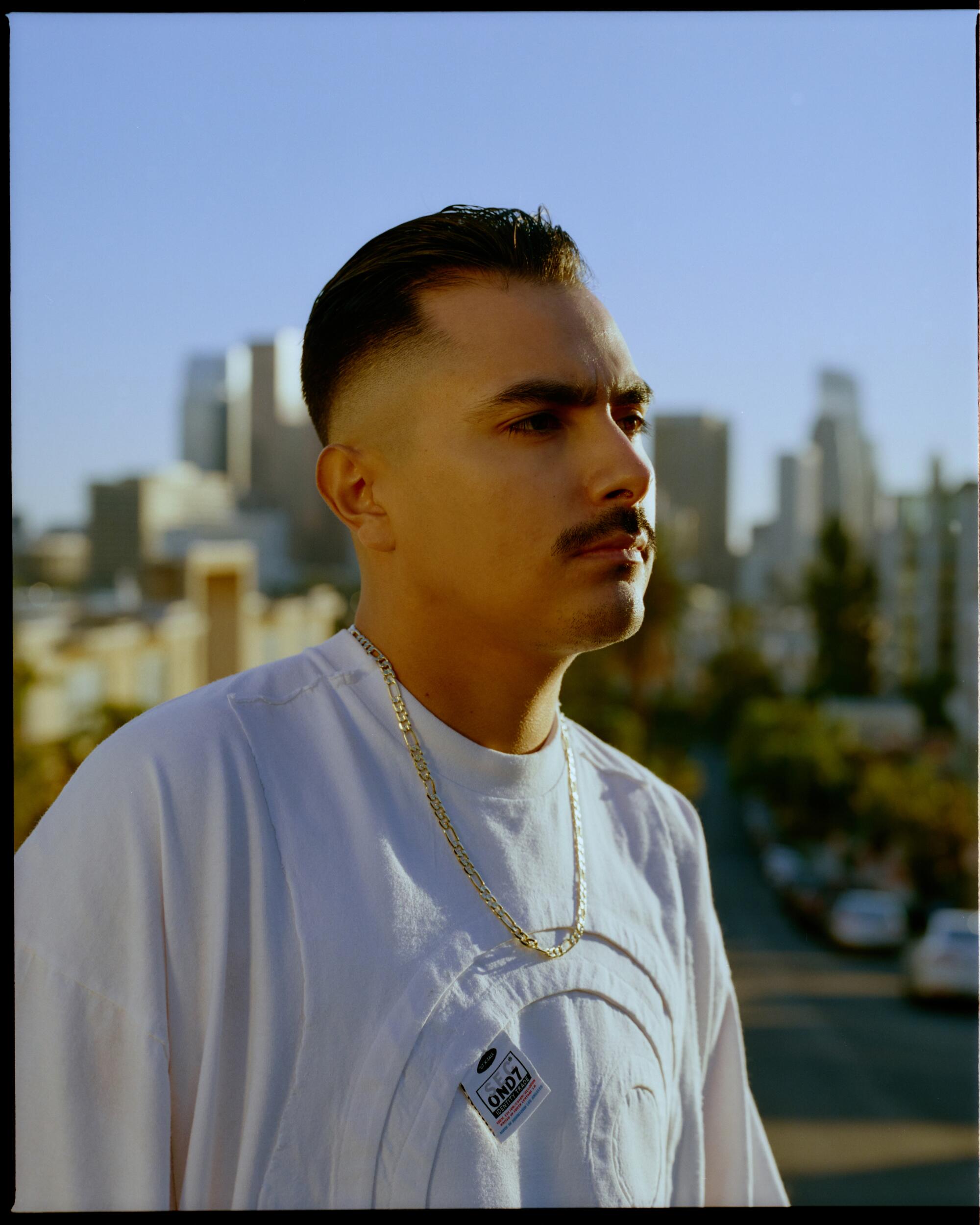

It’s no surprise that the looks Homies depicted hold up today. The kind of style captured by Gonzales had a timeless quality to it, feeling both of the past and of the future. Like it predicted that we’d all be again reaching for clothing three times our size in 2022. We’ve seen the style transcend time and space precisely because it’s connected to culture and lived experience, passed down from friends to friends, family to family. Each generation may put its remix on it, but parts of the look remain classic, immune from trend. Take the never-out-of-style white tees or the crisply creased pants.

Even so, Gonzales admits, the subculture’s sartorial mark is having a moment in the larger world of pop culture and art. “It’s back very strong,” he says. “You’ll see it hanging in malls now: halter tops, pleated pants and big hoop earrings. Girls wearing fedora-style hats and heavy makeup. In five to 10 years, it may be gone for a lot of the outsiders that are wearing it and something else will come in. But it’s never completely leaving the Chicano people.”

On Instagram, fans often take inspiration from Homies — on nails, in art. Sometimes people dress as exact replicas of the figurines. Gonzales, who is active on his account @homies.artist, once saw a follower dressed up as La Negra, a “dark-skinned Latina” who “loves to wear black” and puts on “funky choreographed dance routines at the clubs and parties.” Everything — from the backwards pageboy hat to the baggy black suit and large silver belt buckle — was on point in the re-creation. Another did her take on Chuca, a character from the 1940s, whose name is short for “Pachuca.” She wore lavender cigarette pants with a white bustier, hoping to tap into the personality Gonzales described so eloquently in Chuca’s bio: “Complete with a lady [pompadour] hairstyle (where she hides things) and some white rimmed cat-eye sunglasses, from an era gone by. Together with the Homie Chuco, these two as a couple are the zoot suit Boogie, Swing and Jitterbug Champions of East L.A.”

For some, Homies remain an ode to Chicano beauty. Naysayers thought differently, and they made it known in the early 2000s. LAPD claimed Homies were glorifying gang life. Some cultural advocacy groups said they were reductive and relied too heavily on stereotype (and not just for Chicanos — Gonzales named one of his only Black characters “Shaneequa”). Other critics called them exploitative. Gonzales remained steadfast in his response to these complaints through the years, that his creation was “a reflection of daily life.”

To the more curious observer, Homies’ approach was part of a different documentarian tradition: archiving style holistically, across time, geography, tastes, class, race. The Homies universe was its own kind of fashion catalog, like an old issue of Vogue. Spend some time scrolling through the looks coming from Çedouze and you’ll wonder whether Homies functions as source material. The L.A. brand founded by South Gate-raised designer Guillermo Juarez was inspired by lowrider culture, music and history in L.A. Çedouze’s signature look: oversized workwear, hoodies, T-shirts and tank tops accentuated with large silver grommets the size of a bangle. Shirts nearly reach the knees; the shorts, closer to the ankles. The pants balloon out like a very chic parachute. It’s a flex in over-exaggeration, a lesson in taking up space. Juarez’s latest collection looks like it could adorn the next season of Homies Go High Fashion.

Similarly, Homies may factor heavily in the imagination of Willy Chavarria, the designer who grew up being influenced by Chicano culture in his native San Joaquin Valley. The Ballroom Chinos from Chavarria’s SS22 presentation — chinos with so many pleats, plus a width and height so outrageous they resembled the bottom half of a ballroom gown — are just one example of the collection’s dedication to proportions. (This is something Homies always did well, with tees and pants draping over the small plastic bodies, often taking up most of the surface area.)

Perhaps Homies is best understood as a look book of culture, with what Gonzales created being akin to other archival projects that have sprouted up in our more democratized internet era. For many contemporary artists and designers, documentation is grounding, a focal point from which to explore political themes, ideas, identities, style, narratives and more. Another archive of the Homies era is Veteranas and Rucas, artist Guadalupe Rosales’ longtime dedication to Chicanas in L.A. The project shares vintage photos of Latinx youth culture from across California. It’s easy to become inspired scrolling through the photo-booth shots of impossibly sophisticated (often young) women with their eyebrows shaved off, lips darkly lined, waves crunchy from mousse or hairspray, hoop earrings grazing their shoulders. It’s also easy to see how the style has persisted and evolved among women in L.A.

When I open Instagram today to black-and-white photos of Latinx models with big hair and mocha-colored lips, I know that they’re drawing their own line to these histories. Honoring them in a way that’s active and alive. You can’t tell if these photos were taken in 1998 or 2022, and that’s what makes them special. “It’s timeless,” Gonzales says of the look he helped enshrine forever with Homies.

Homies encapsulated a style that has been passed down like an heirloom. And so have the Homies themselves. My uncle’s Homies have been played with (and lost) by his children. A friend at a party recently told me she’s lugged her Homies, purchased for 50 cents apiece at a laundromat or grocery store quarter machine in the early aughts, through various apartments and phases of life. The resale market online is active, an entire series going for as much as $400 on eBay. In the same way some people pass down model airplanes or a vintage set of toy cars, we pass down Homies.

Preservation comes in many forms. In December, Gonzales is releasing the 14th set of Homies, bringing the number of characters up to around 300. “I went to the Super Legends Cruise in Long Beach. It had War, Tower of Power, Los Lobos, Brenton Wood. The entire ship looked like my cartoon characters. It doesn’t surprise me, because I know they’re not playing dress-up. It’s not Halloween,” he says.

Homies used style as a storytelling device. The more stories Gonzales told, the more his fashion archive grew. The collection lives in the memory boxes, shelves and displays of collectors, but it also lives online, in a 2.0 website that houses most of the Homies he’s ever created. Each name is accompanied by an illustration and backstory — the reasons they’re presenting in this way.

and Julianna Aguirre Martinez.

You can refer to Bruja, who wears all black with wild, wavy hair to match her a.k.a. Or La Dumpy, the official stylist for the “Homiegirls” whose specialty is “fierce Aquanet hair with that wet look, and Sharpie eyeliner” and deep red lipstick lined with black. Or Gata, who wears a shrunken pinstriped vest as a shirt and is the designer of her own fashion line, Chulawear.

Something about looking back on this archive makes us ask questions of ourselves that Homies seemed to have the answer to: Who am I, and how to do I communicate that to the world through my look?

Photography: Darren Vargas

Styling: Keyla Marquez

Hair: Jocelyn Vega

Makeup: Selena Ruiz

More stories from Image