World leaders head to Scotland for global climate talks. Here’s what you need to know

WASHINGTON — Some 30,000 heads of state, environmental activists, business leaders and journalists are expected to descend on Scotland on Sunday for a climate summit that comes as world leaders are running out of time to break away from fossil fuels and prevent the most catastrophic effects of global warming.

Climate scientists say this year’s United Nations conference is critical if the world is to hold rising temperatures to 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) above preindustrial levels. Beyond that threshold, the dangers posed by extreme heat, floods and wildfires increase exponentially.

But the challenges are immense. Chinese President Xi Jinping is not expected to attend in person, despite running the country that ranks first in the world for carbon emissions. India, Russia and Australia, all major fossil-fuel producing countries, have not announced more ambitious goals to slash emissions, as is expected of all countries this year. And the United States’ credibility as a climate leader will suffer if congressional Democrats are unable to agree on new climate legislation this week, sending President Biden to Glasgow empty-handed.

Though the climate summit is held annually, diplomats and scientists say the decisions made in the next two weeks will be the most important since the Paris agreement of 2015. While many believe getting leaders together in the same room is key, hopes for a major breakthrough are dim. Whether the summit succeeds depends on global leaders’ willingness to go beyond the progress they’ve already made and pledge further emissions cuts.

What is COP26?

The 26th gathering of the Conference of Parties, or COP26 for short, is unlike other global summits that are restricted to only the wealthiest and most powerful countries. Each year, this conference brings together the 197 nations and territories that signed onto the original 1992 U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change, the first global agreement to recognize the threat that human behavior could pose to the climate.

This year, the conference is being held in Glasgow from Sunday to Nov. 12.

Leaders come to COP with their own ambitions, but the summit’s overarching goal this time is to build off the 2015 Paris climate agreement, which requires countries to report on their progress cutting emissions and to announce new climate targets every five years. The U.N. has no ability to enforce these pledges, and many countries, including the U.S., have fallen far short of their promises. But peer pressure can be a powerful tool — if the countries wielding it have credibility.

Governments’ failure to take aggressive action looms large as leaders head to the COP26 climate summit, billed as ‘the last, best chance’ to save Earth.

Who will attend?

There are essentially two conferences happening at the same time. The first is the official diplomatic meeting attended by more than 100 heads of state and their delegations who will conduct negotiations over emissions targets and financial assistance to help poorer countries cope with climate change. The U.S., the world’s second-biggest carbon emitter, is expected to have a large showing led by Biden, Secretary of State Antony J. Blinken and other Cabinet officials, as well as U.S. climate envoy John Kerry. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi is bringing a delegation of Democrats to serve in a “reinforcing role,” Rep. Jared Huffman (D-San Rafael) told The Times. And several House Republicans are expected to attend, led by Rep. Garret Graves of Louisiana.

Outside of the diplomatic “blue zone” — so-named for the blue-colored badges required to enter areas where inter-governmental talks are taking place — a second conference attracts the leaders of multinational corporations, Wall Street bankers, celebrities and climate activists who hope to get face time with world leaders or at least their representatives. Leonardo DiCaprio, Bill Gates and Jeff Bezos are among those expected to attend, according to a Politico report.

Many attendees go to draw attention to their causes. Others go because the two-week-long event, like most international conferences, is also a business opportunity and a forum to rub elbows with the wealthy while branding one’s interests as climate-related.

What are the big disagreements?

The fiercest debates will center on whether wealthy countries are putting forward climate pledges that are ambitious enough to change the world’s current trajectory, which is heading toward roughly 3 degrees of warming by 2100.

China, in particular, is under pressure to put new limits on its domestic coal consumption. Though the country pledged to stop financing the construction of coal-fired power plants overseas, it continues to approve new ones at home that will ensure it burns a lot of coal for decades to come. Recent power outages and coal shortages have made it unlikely that China’s leaders will abandon coal anytime soon.

The rest of the world may suffer the consequences if the U.S. and China don’t work together on reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Australia, one of the top producers of coal and gas, recently announced that it will pledge to reach net-zero emissions by 2050. But Prime Minister Scott Morrison has balked at raising the country’s emissions reduction goal for 2030 and is facing criticism for putting forward a plan that environmental advocates view as weak and overly reliant on new technology and consumer behavior, rather than legislation.

Money is also a recurring source of tension.

Rich nations responsible for the bulk of the greenhouse gas emissions causing global warming have promised for decades to set aside money to help poorer countries transition away from fossil fuels and adapt to climate change. In 2009, the U.S. and other developed nations agreed that by 2020 they would provide $100 billion a year to developing countries, which are among the most affected by climate change.

But wealthy countries have fallen short, failing to raise more than $80 billion annually. Just days before the start of the summit, Canadian and German diplomats announced that they might be able to raise the money by next year and expressed confidence that they would meet their commitment by 2023.

How the group plans to make up for shortfalls this year and in 2020 is unclear. Meanwhile, environmental groups and leaders of developing countries say $100 billion is not nearly enough.

“This is a tough issue,” said Alden Meyer, a senior associate at E3G, a European climate think tank. Industrialized countries fear the prospect of being on the hook financially for decades of fossil fuel pollution, he said. But for the vulnerable countries, he added, climate change is an existential threat.

How much can COP26 really affect climate change?

If the next two weeks result in a series of detailed climate pledges from countries responsible for the majority of carbon emissions, then the conference could have a huge effect — especially if countries follow through on those promises.

But experts in international climate negotiations say that regardless of what happens in Glasgow, most of the work of pivoting away from fossil fuels toward cleaner energy will continue to be done at the national and local level rather than through international diplomacy. For this reason, the details of net-zero emissions targets announced by business and civic leaders before and during these conferences are closely scrutinized.

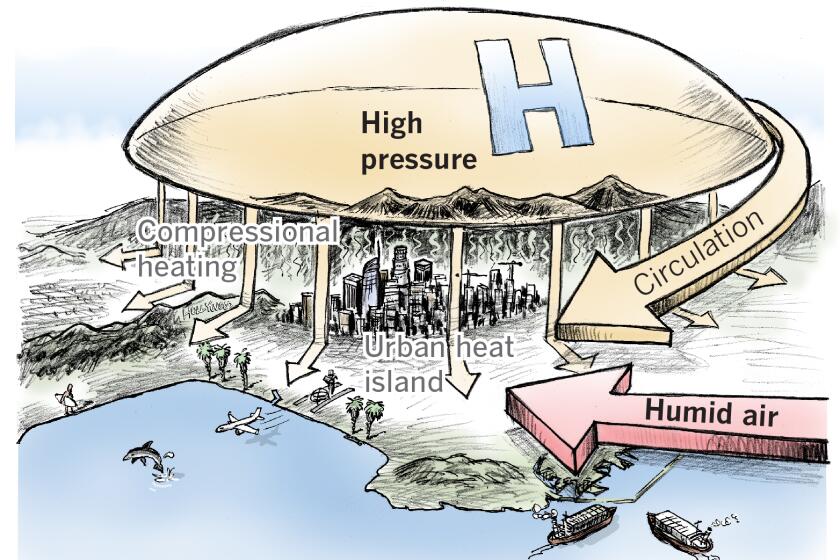

California’s worst heat waves arrive in a one-two punch — high temperatures combined with humid air from Baja.

“Ultimately, what really matters in most of the world is what happens inside companies,” said David Victor, a professor of international relations at UC San Diego. “They’re watching this whole process for direction of travel.”

The spread of COVID is still a major concern. Why is this summit being held in person?

COP26 was initially scheduled to be held at the end of 2020, but between the rapid spread of COVID-19 and the lack of vaccines, Britain, the host of the talks, asked for it to be postponed. A coalition of more than 1,500 environmental advocacy groups called for the summit to be delayed again this year, arguing that vaccines are still impossible to come by in parts of South America, Asia and Africa and would prevent the leaders of many developing nations from meeting the event’s attendance requirements. But despite concerns over equity — and the fact that flying thousands of diplomats to Scotland generates a huge amount greenhouse gas emissions — the U.N. pressed forward.

Karen Orenstein, director of the climate and energy justice program at Friends of the Earth, one of the organizations calling for a delay, said the conference is fundamentally not an equal playing field, but it would tilt even more in favor of wealthy countries if it were held virtually. Spotty Wi-Fi access, technology failures and large time zone differences would likely exclude more representatives from poorer nations than an in-person conference, she said.

The conference “is a closed, elite process, but it is the only process,” Orenstein said. “And it’s really critical that voices from the global south and frontline voices in the U.S. are heard.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.