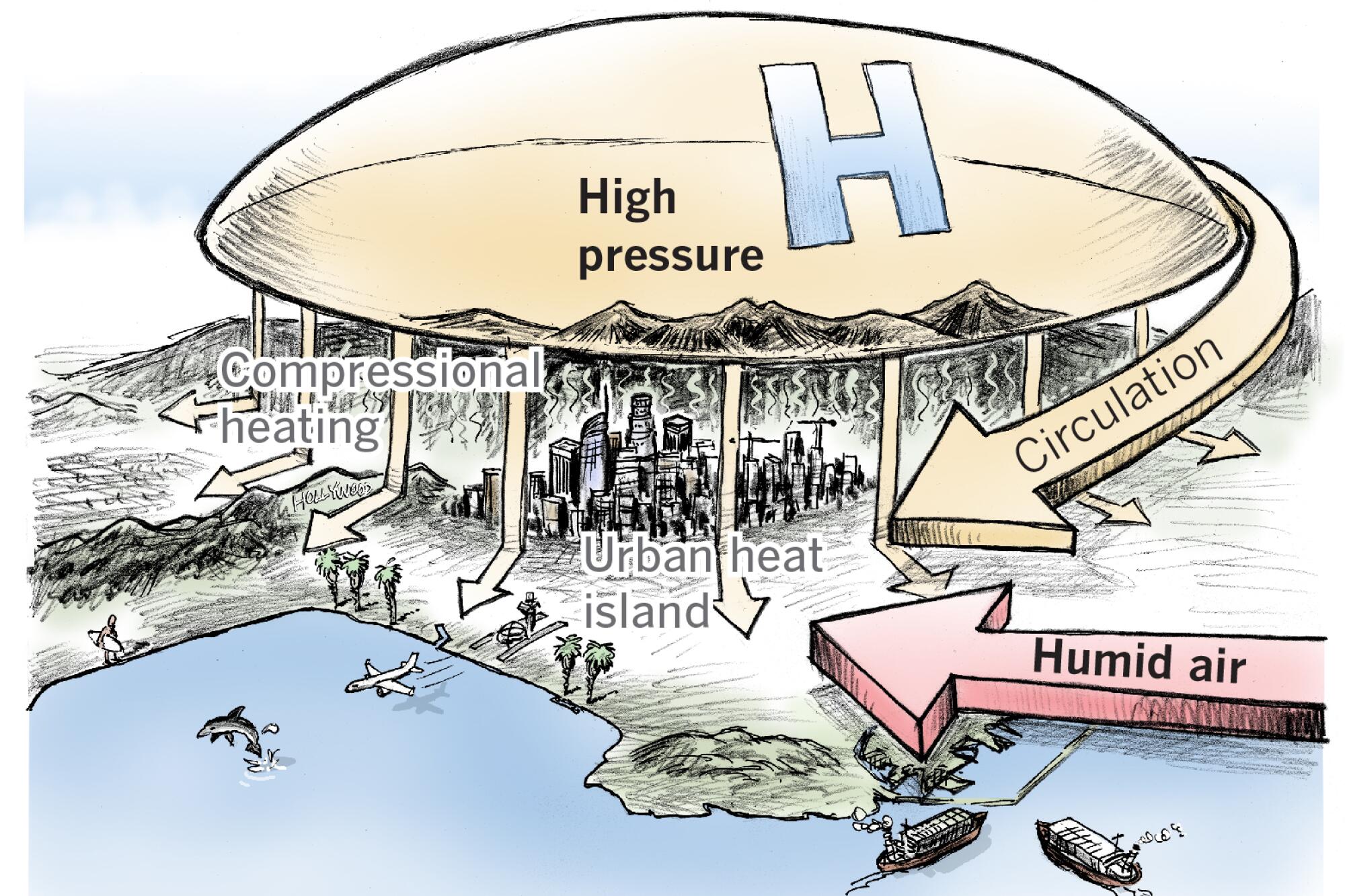

When a major heat wave hits Southern California, it begins with a jab — a ridge of high pressure builds over Nevada or Mexico and sweeps into the region, bringing scorching temperatures along with it.

Then comes the right hook: A mass of humid air created by unusually warm ocean water just off the northern coast of Baja California moves in from the southeast. Combined, they deliver a deadly blow, wreaking havoc on heavily populated regions such as Los Angeles County.

“We understand pretty well how and why they form,” said Glynn Hulley, a climate scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory who has documented a shift toward hotter, more humid heat waves in urban areas of Southern California since 2000. “It’s almost like the heat waves have changed their personality, shifting to warmer and more humid nighttime events.”

Climate change is transforming the character of the West’s hottest periods — making them more frequent, more persistent, more humid and more lethal. Experts say this shift in heat waves should prompt changes in emergency notifications and public health response to keep the death toll from rising. But that isn’t happening.

In California and some other states, key strategies that could protect the most vulnerable people and save lives, including urban cooling measures and better warning systems, remain a low priority compared with other environmental hazards such as wildfires. Environmentalists and health advocates see it as a major shortcoming in the state’s efforts to adapt to the warming climate.

California chronically undercounts the death toll from extreme heat, which disproportionately harms the poor, the elderly and others who are vulnerable.

“Whatever we’re doing isn’t working, and it’s only getting worse,” said Kathy Baughman McLeod, a climate resilience specialist at the Atlantic Council, a Washington think tank. Her organization formed a group of public health experts, governments and nonprofits to push authorities to begin naming and categorizing heat waves, just like hurricanes, and take other steps to better highlight the dangers.

“We’ve got to try something new and powerful to wake people up to this deadly threat,” she said.

Climatologists say there is still time to slash the buildup of greenhouse gases that is warming the planet. But even with strong action, the carbon dioxide that has accumulated in the atmosphere is projected to deliver more dire heat extremes over the next few decades.

Consider the 2006 heat wave in California. In July of that year, hospitals along the California coast were overwhelmed with patients as record-high temperatures settled over the state for nearly two weeks. Bodies piled up in coroner’s offices in the Central Valley. Though state records showed that about 140 people died from the heat, researchers later estimated that there had been 650 deaths.

Scientists predict that this type of heat wave, the kind that once struck about every 50 years, is now occurring every 10 years. Across the state, extreme heat days — defined as those with temperatures exceeding the 98th percentile — are expected to be about four times more frequent in the next 20 years compared with historical levels. Deaths are projected to climb.

To study the shift, NASA’s Hulley ranked California heat waves, indexing them by their duration and intensity. He found that all of the state’s worst heat waves have occurred since 2003. He also determined that the length of the state’s heat season is rapidly expanding, with extremely hot temperatures showing up as early as March and lingering into September and October.

Since the mid-1980s, scientists have also documented a shift to hotter, more humid nights, a lethal combination that prevents people from recovering after a day of soaring temperatures. Humid heat waves are more dangerous because muggy, moisture-laden air makes sweating less effective at shedding heat from the body through evaporation.

Environmentalists and other advocates see a disconnect between worsening heat waves and California’s response. They say that, along with slashing emissions, government can save lives by improving communication of the risks to the public and instituting community programs to check on neighbors who are isolated, elderly or medically fragile.

Read all of our coverage about how California is neglecting the climate threat posed by extreme heat.

“We have a real challenge in front of us in how to get people to understand,” said Kristie Ebi, a professor in the Center for Health and the Global Environment at the University of Washington. “Yes, you’ve been through heat waves before. But these heat waves are hotter, they’re more intense, they last longer, they’re more deadly.”

As it is now, the National Weather Service bases its heat advisories, watches and warnings on established thresholds, including the heat index, minimum and maximum temperatures and the duration of the heat, and issues them when they exceed certain levels.

But public health experts have long complained that the weather service’s approach is too conservative and does not account for heat waves that may not exceed those thresholds but nonetheless send people to the hospital. In a 2014 study, scientists identified 19 heat waves in California, which landed more than 11,000 people in the hospital in 1999 and 2000. The weather service issued heat advisories for just six of the events.

The weather service has updated its approach in the Western U.S. in recent years by issuing advisories, watches and warnings using a new method that forecasts heat risks over the next seven days using a color-coded scale like the air quality index.

Kimberly McMahon, public weather services program manager for the National Weather Service, said the online tool, known as HeatRisk, was developed in response to a 2013 request from the California Office of Emergency Services. It pulls in a broader array of climate data, including unusually high and low forecast temperatures, the degree of cooling overnight and health data to account for populations that are more vulnerable to the heat.

The tool, however, is labeled as “experimental” and described as “supplementary to the official NWS heat watch/warning/advisory program.”

McMahon said the weather service is working to simplify its messaging on the dangers of extreme heat as part of a “comprehensive strategy for conveying lifesaving heat information.”

Researchers and health experts favor a more expansive alert system that warns the public about heat waves not only based on temperature thresholds but also on the public health effects they’re expected to cause, particularly to elderly and infirm people, outdoor workers and other sensitive populations.

Utilities have funds available to install air conditioning in low-income households, but for one California family, help did not come soon enough.

“We know heat puts health at risk in vulnerable people well below temperatures that a heat alert would be given,” said Dr. Aaron Bernstein, a pediatrician at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

In some areas it does not take record-setting temperatures, or even summer weather, for the heat to be lethal. Southern California is the only place in the U.S. where scientists have documented heat-related deaths during the winter, due to the hot, gusty Santa Ana winds. Though rare, these unseasonal heat waves are believed to be especially dangerous because they strike at a time when people are accustomed to cooler weather.

The temperature at which heat becomes life-threatening also varies widely depending on local variables.

In San Francisco, where the climate is usually mild, and relatively few people have air conditioning, a heat wave during the 2017 Labor Day weekend that reached a record-breaking 106 degrees — 37 degrees above average — doubled the volume of 911 calls and killed several residents. The same temperature has far less dramatic impacts in a place such as Palm Springs, where air conditioning is widespread and people are more acclimated to triple-digit temperatures.

Baughman McLeod — who directs the Atlantic Council’s Adrienne Arsht-Rockefeller Foundation Resilience Center — said her organization is developing a system to assign heat waves names and categories, an effort aimed at pushing individuals and government officials to take the threat of extreme heat more seriously.

L.A. County and Miami-Dade County are among the first cohort of communities where the group hopes to test such alerts.

Issuing names for heat waves at a national level would ultimately require the participation of the federal government, but for now, the National Weather Service “does not have any plans to start naming heat waves,” spokeswoman Jasmine Blackwell said.