It was a typical summer day in Los Angeles, but a satellite orbiting hundreds of miles above Earth could detect that it was getting much hotter in some neighborhoods than others.

In a majority-white area of Silver Lake — where median household income is more than $98,000 a year and mature trees dapple the hilly streets with shade — the surface temperature was 96.4 degrees.

Less than a mile away, in a corner of East Hollywood, it was 102.7 degrees. The predominantly Latino and Asian area, where median household income is less than $27,000 a year, is packed with older, two- and three-story apartment buildings. It has few trees big enough to provide shade, and less than one-third the canopy of Silver Lake, ranking it among the lowest-coverage areas in the city.

“Look up and down the street, there’s not a lot of trees down here,” said David Paque, who lives in that part of East Hollywood in a wood-sided, one-story house built in 1919 that on summer afternoons can feel 10 degrees hotter inside.

Such “thermal inequities,” as scientists call them, checker the landscape of L.A. and other cities as they heat up from climate change. In a recent study that used satellite data from 2013 to 2019, UC Davis researchers found that California’s metro areas have greater temperature disparities between their poorest and wealthiest neighborhoods than any other state in the southwestern U.S.

That doesn’t come as a surprise to Paque. He knows global warming is making summers more brutal and has spent nearly 20 years turning his frontyard into a shaded refuge of guava, mango and avocado trees to shield his property from heat. But he fears rising temperatures will only make his neighborhood more miserable.

“I’m worried about the kids, our babies, and what kind of future they’re going to have,” Paque, 57, said. “What planet are we leaving them?”

Extreme heat is killing far more Californians than the state acknowledges, a Los Angeles Times analysis has found, but climate change isn’t the only cause of this rising toll.

People’s risk of heat-related illness and death is also a product of the built environment around them. The amount of paved surfaces and tree cover where they live and work, the quality of their housing and their ability to pay to cool their surroundings can make the difference between death or mere discomfort.

The unequal distribution of cooling infrastructure in Los Angeles and other cities is a big reason the health effects of worsening heat waves fall disproportionately on the poor and communities of color while those with money and privilege remain relatively shielded from the problem — by trees and parks, better housing and the power to crank up the air conditioning whenever they want.

California chronically undercounts the death toll from extreme heat, which disproportionately harms the poor, the elderly and others who are vulnerable.

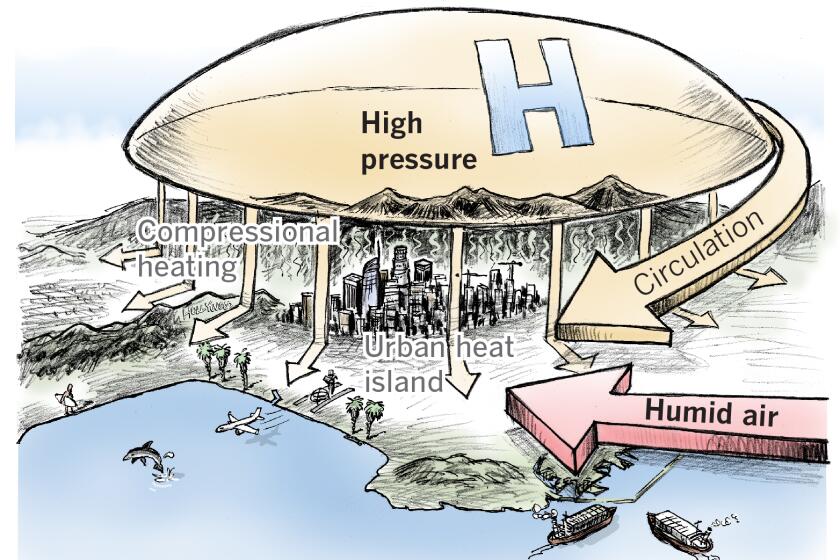

Fueling these disparities is the heat island effect: Neighborhoods with few trees and a lot of pavement, large buildings and other heat-absorbing surfaces can be 10 degrees warmer than surrounding areas.

Black, Asian and Latino Californians are more likely to live in these hotter areas, in part because of a history of discriminatory redlining policies that excluded them from real estate investment, and environmental racism that targeted their neighborhoods for industrial facilities and freeways instead of parks and green space.

“These microclimates aren’t natural, they are man-made,” said Rachel Morello-Frosch, an environmental health scientist at UC Berkeley. She called them “legacies of racist decision-making” that decades later “still determine how resilient neighborhoods can be in the face of climate change events like heat waves.”

State and local officials said that as they work to slash planet-warming emissions, they are also taking steps — planting trees and switching to solar-reflective roofs and pavement — to cool neighborhoods that suffer disproportionately. But such improvements could take decades to be felt, leaving some residents to wonder why more isn’t being done to help with air conditioning, insulation and other protections that could provide immediate relief and help save lives now.

Housing risks

During heat waves, indoor temperatures can build to levels higher than outdoors and persist well into the night as buildings slowly radiate the heat they’ve absorbed. People living in older, less insulated homes are at higher risk from extreme heat, especially if they lack air conditioning or can’t afford to run it.

Pacoima, one of the hottest neighborhoods in Los Angeles, is in an area that has warmed nearly two degrees since the San Fernando Gardens — a 448-unit public housing complex — was completed there in 1955, according to the research nonprofit Berkeley Earth. The city housing authority doesn’t provide air conditioning, however, and those who have installed it often struggle to pay their electric bills. As a result, tenants must invent ways to cope with ever more punishing heat spells.

Juan Duran and Wendy Mejia said it gets so hot inside their unit in the low-slung development of blocky, garden-style apartments that they can literally see waves of heat rising through the air into their teenage daughter’s upstairs bedroom.

“The second floor is unbearable,” Duran said, so bad that as a present for her middle school graduation, his daughter asked for an air conditioner.

Read all of our coverage about how California is neglecting the climate threat posed by extreme heat.

Each year Mejia plants sunflowers to shade the building. On summer afternoons she hoses down the exterior of its cinder block walls. She’ll take three or four showers a day just trying to stay cool.

Mejia, who manages a McDonald’s, and Duran, a convenience store clerk, said they don’t earn enough to run air conditioners around the clock. Instead, they spend their free afternoons outside their home under a sliver of shade and grill food to avoid using the stove inside. At bedtime they crank up the air conditioning unit they installed upstairs to create a cool zone, but much of the rest of the house remains uncomfortably hot.

“With the heat you feel suffocated,” Mejia said, “like you can’t breathe.”

Lizette Gonzalez, 32, who lives in San Fernando Gardens with her husband and five children, said she can feel the heat radiating into her apartment by touching its block walls from the inside.

They’ve installed one air conditioner and use fans to try to blow the cooled air around the house. But after five years living here, Gonzalez said, she does not understand why her unit did not come with air conditioning to begin with.

“They provide heaters, so I don’t know why they don’t provide air,” she said. “Without a heater you can use blankets. But without A/C, even if you’re indoors, you can’t cool down.”

The housing authority said that most of the city’s public housing was built between the 1930s and the 1950s, before air conditioning was considered essential. The agency said it lacks the money to install air conditioning now.

Gonzalez said her family deals with the heat by drinking ice water, using a kiddie pool outside or escaping to an air-conditioned mall so their youngest can cool down enough to fall asleep. One summer day it got so hot Gonzalez resorted to putting the kids in the tub with ice.

“I don’t know what else we can do to withstand this heat,” she said.

What are heat-related illnesses and how are they treated? Are they preventable or inevitable? We talked to health experts for the answers.

Much of California’s housing stock was built before energy efficiency standards first took effect in the 1970s, and those older buildings pose elevated risks because they tend to be less well insulated, said Max Wei, research scientist at Lawrence Berkeley National Lab. “These homes heat up more quickly and the upper floors can be even higher temperature,” he said.

Wei, who is conducting a multiyear research project in Fresno aimed at helping vulnerable communities better withstand extreme heat, said that there needs to be more focus on preventing people’s homes from overheating and that policymakers should be asking whether air conditioning can be enshrined in California’s building codes.

California law and building codes require residential units to have heating. But there is no requirement for air conditioning.

“As it is now, cooling is used more as an amenity than as a requirement,” Wei said. “We wouldn’t think that homes in the Northeast or Minnesota wouldn’t require furnaces. So why should we think that homes in hot areas don’t require air conditioning?”

Kyle Krause, deputy director of codes and standards at the California Department of Housing and Community Development, said his agency has the power to propose adoption of building standards that address health and safety issues “of statewide significance, however not all climate zones in the state need air conditioning.” He said the issue could be evaluated and discussed with stakeholders and potentially proposed through regulatory action or in response to legislation.

Falling between the cracks

Mobile homes are a particular concern, not only because they are more susceptible to overheating than traditional homes, but because they tend to house more elderly residents who may choose to stay at home even when it is dangerously hot inside. A recently released climate assessment by Los Angeles County found that 56% of mobile home residents live in areas of high heat exposure, compared with 38% of all county residents.

At a mobile home park in the Riverside County community of Desert Edge, residents have for years complained of power outages that come at the worst time imaginable: during bouts of extreme heat that have pushed temperatures above 120 degrees.

When a strong heat wave hit in June, causing a power outage, Porfirio Juarez and Emma Duarte took refuge in a shaded area outside while their 2-year-old and 4-year-old daughters used a portable swimming pool to keep cool. Other residents of the Corkill Mobile and RV Park sat in their cars with the air conditioning on while they waited more than three hours for the power to return.

“People say it’s crazy to live here,” Juarez said. “They tell me to move, but it’s harder to do that when you have a family.”

Dozens of the RV park residents filed a lawsuit in 2019 accusing the property owners of failing to maintain the mobile park, including the community swimming pool that they said was often closed.

Tejas M. Modi, president of Durant Property Investments LLC, which owns the RV park, said he’s trying to fix the electrical problems that have caused outages and other problems raised by residents. He said years of neglect by the previous owner led to the current conditions.

For one former resident of the park, Allan Wanner, 61, the last straw came when his best friend was found dead on the morning of Aug. 8, 2020.

A Riverside County coroner’s report said heart disease and alcohol abuse may have contributed to the death of 59-year-old Gerald Floyd Rice, but Wanner suspects the heat, which reached triple digits that week and brought power outages, played a role.

Wanner, who suffers from congestive heart failure and relies on an oxygen concentrator, said he was sometimes forced to rent a hotel room to escape the heat and have access to reliable power.

Utilities have funds available to install air conditioning in low-income households, but for one California family, help did not come soon enough.

“I can’t do this anymore,” he said before moving in June — to Arizona. “If I don’t get out of here, I’m going to die.”

Patricia Solís, executive director of the Knowledge Exchange for Resilience at Arizona State University, said her research in Maricopa County has found that people who live in mobile homes are six to eight times more likely to die from heat-associated causes than people who live in other types of housing. She said surveys found residents paying as much as $400 a month to cool a space that’s the size of a large room. She has taken readings inside trailers where people were living with temperatures as high as 115 degrees.

“They’re like tin cans on a parking lot,” Solís said.

But mobile homes are ineligible for federal aid such as the Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program, which helps millions of households with their power bills, because they are not counted as structures, Solís said. People living in trailer parks may also miss out on utility company assistance programs because they are often not direct customers and instead pay their landlords through a parkwide account.

“So they fall between the cracks,” Solís said.

An uneven toll

In their study of 20 metro areas in the southwestern U.S., UC Davis researchers found that on extreme heat days, California’s poorest neighborhoods were nearly five degrees hotter, on average, than the wealthiest neighborhoods. Their research found an even stronger correlation for the most heavily Latino neighborhoods, which in the Los Angeles area were found to be 6.7 degrees hotter than neighborhoods with few Latino residents.

The effects of rising temperatures are expected to grow significantly in the coming decades, according to a climate vulnerability assessment released this month by Los Angeles County. It found that more than 1 million people live in areas of the county that by midcentury will experience an additional 30 extreme heat days a year, with the largest temperature increases expected in the San Fernando and Santa Clarita valleys.

The assessment also found that Black and Latino residents face disproportionate risk. Latino residents make up 48.5% of L.A. County but 66.9% of the population in communities identified as having high vulnerability to extreme heat.

“That points to a history of disinvestment in those communities, where there’s a lack of tree canopy, a lot of hot, paved surfaces and older housing stock that’s less well insulated and less likely to have air conditioning,” said Gary Gero, the county’s chief sustainability officer.

Extreme heat is endangering California warehouse workers, who often labor without air conditioning.

In a study published last year, researchers found that in cities across the U.S., land surface temperatures in formerly redlined neighborhoods — areas the federal government designated nearly a century ago as “hazardous” to real estate investment due largely to their racial makeup — are nearly five degrees hotter than other areas. Study authors wrote that historical housing policies, such as denying residents federally backed home loans, may be directly responsible for their disproportionate exposure to heat.

Those underpinnings make heat a “discriminating killer,” said study co-author Vivek Shandas, a professor of urban studies and planning at Portland State University. “Heat waves don’t just kill people by coincidence. There’s really a set of conditions that are in place.”

Growing resilience

There are ways to alleviate the uneven toll. California could invest in the “physical environments of these neighborhoods that have disproportionately suffered from these heat waves,” said UC Berkeley’s Morello-Frosch, who has studied the health effects of extreme heat and disparities in access to green space.

Improving the quality and insulation of housing and enhancing green space can save lives, she said, and tree planting is especially effective. One study conducted in Madison, Wis., found that tree canopy coverage above 40% can cool the air by as much as 10 degrees.

“The path to protecting public health is fairly straightforward,” Morello-Frosch said. “We just need to have collective will and invest the resources to make it happen.”

A 2020 study by a group of researchers and experts called the Los Angeles Urban Cooling Collaborative found that widespread tree planting and installation of solar-reflective roofs and pavement could reduce temperatures in Los Angeles enough to save 1 in 4 lives currently lost to heat waves, largely in low-income neighborhoods and communities of color.

Los Angeles changed its building code in 2014 to require reflective “cool roofs” and in recent years has begun pouring cool pavement designed to reflect more of the sun’s rays in some of its hottest neighborhoods. The city plans to coat 200 more city blocks by next summer, said Greg Spotts, assistant director of the Bureau of Street Services.

Los Angeles officials are also pushing to plant more trees across the city and increase canopy in the highest-need areas. But the city appears to be falling short of reaching Mayor Eric Garcetti’s 2019 goal to “plant and maintain” at least 90,000 trees by the end of this year.

Just over 54,000 trees had been planted on public and private property by the end of August, City Forest Officer Rachel Malarich said.

Malarich said the environmental benefits from increasing tree canopy are “not just about the number of trees planted, but what species are planted and where they are planted.” She said the city is working to plant trees in high-need areas, but acknowledged being constrained by insufficient data, responsibilities that are spread across several city departments and differing levels of community interest in receiving and caring for the trees.

California’s worst heat waves arrive in a one-two punch — high temperatures combined with humid air from Baja.

Malarich said the city is about halfway through conducting a neighborhood-by-neighborhood tree inventory that will help guide its efforts to grow and manage its urban forest.

In Watts, the groups North East Trees and TreePeople are in the middle of a multiyear effort to plant thousands of trees in the shade-poor South Los Angeles neighborhood. It’s part of a state-funded project to gird the area for the impacts of climate change. The goal is to saturate the community with trees wherever there is room, including along parkways and sidewalks, and by distributing free fruit and shade trees to residents to plant in their yards.

Slender saplings are being spread around the predominantly Black and Latino neighborhood and staked outside of schools and next to houses and apartments. They will need years of supplemental watering before they can survive on their own.

A row of young African fern pines now stands between busy Imperial Highway and the Imperial Courts public housing complex. Someday, they will provide shade for the hot, south-facing side of the apartment buildings, as well as buffer vehicle noise and pollution.

“It’s going to completely cool off this entire block,” crew supervisor Ladale Hayes, 44, said as he stood next to the row of 10-foot-tall trees planted into holes cut out of the sidewalk. “It was a bare sidewalk with no shade canopy whatsoever. And now those trees are flourishing.”

Longtime Imperial Courts resident Loretha West, 78, dutifully waters the paperbark tree Hayes planted last year outside her apartment, which she requested as a memorial to her son, who was murdered at age 29.

West said she is looking forward to when its smooth green leaves spread overhead and help cool her building.

“I’m proud of the tree,” she said, “and I will take care of it as long as I’m here.”

Times staff writer Sean Greene contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.