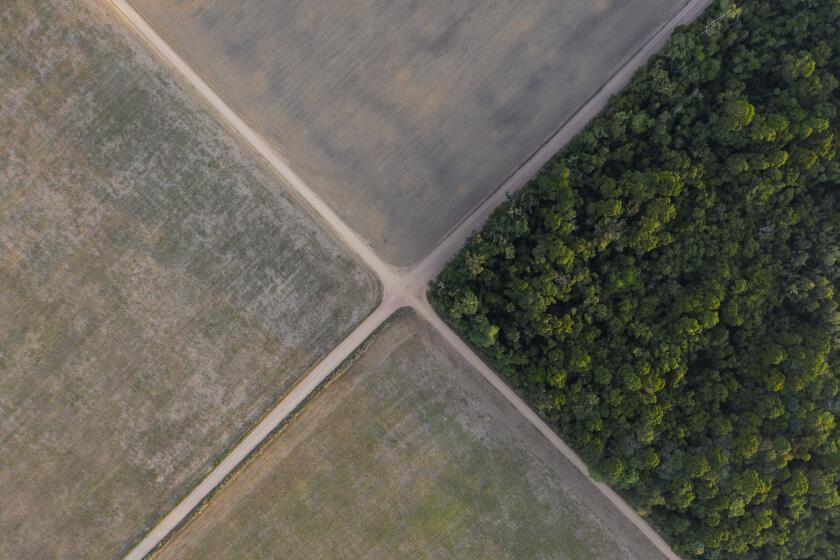

More than 100 countries, including U.S. and Brazil, vow to end deforestation by 2030

GLASGOW, Scotland — More than 100 countries pledged Tuesday to end deforestation in the coming decade — a promise that experts say would be critical to limiting climate change but one that has been made and broken before.

Britain hailed the commitment as the first big achievement of the United Nations climate conference, known as COP26, taking place this month in the Scottish city of Glasgow. But campaigners say they need to see the details to understand its full effect.

The British government said it had received commitments from leaders representing more than 85% of the world’s forests to halt and reverse deforestation by 2030. Among them are several countries with massive forests, including the U.S., Brazil, China, Colombia, Congo, Indonesia and Russia.

More than $19 billion in public and private funds has been pledged toward the plan.

British Prime Minister Boris Johnson said that “with today’s unprecedented pledges, we will have a chance to end humanity’s long history as nature’s conqueror, and instead become its custodian.”

Forests are important ecosystems and provide a critical way of absorbing carbon dioxide — the main greenhouse gas — from the atmosphere. Trees are one of the world’s major so-called carbon sinks, or places where carbon is stored.

New study says climate change is essentially two-thirds to 88% responsible for the conditions driving wildfire woes in the western United States.

But the value of wood as a commodity and the growing demand for agricultural and pastoral land are leading to widespread and often illegal felling of forests, particularly in developing countries.

Experts cautioned that similar agreements in the past have not been honored.

Alison Hoare, a senior research fellow at the Chatham House think tank in London, said world leaders promised in 2014 to end deforestation by 2030, “but since then, deforestation has accelerated across many countries.”

“This new pledge recognizes the range of actions needed to protect our forests, including finance, support for rural livelihoods, and strong trade policies,” she said. “For it to succeed, inclusive processes and equitable legal frameworks will be needed, and governments must work with civil society, businesses and Indigenous peoples to agree, monitor and implement them.”

Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro is sending troops to the Amazon in a bid to curb surging deforestation, but skeptics doubt its effectiveness.

“We are delighted to see Indigenous peoples mentioned in the forest deal announced today,” said Joseph Itongwa Mukumo, an Indigenous Walikale and activist from Congo.

He called for governments and businesses to recognize the effective role Indigenous communities play in preventing deforestation.

Luciana Tellez Chavez, an environmental researcher at Human Right Watch, said the agreement contains “quite a lot of really positive elements.”

The European Union, Britain and the U.S. are making progress on restricting imports of goods linked to deforestation and human rights abuses, “and it’s really interesting to see China and Brazil signing up to a statement that suggest that’s a goal,” she said.

Heads of state, environmental activists, business leaders and journalists are in Scotland for a climate summit that comes as world leaders are running out of time to break away from fossil fuels and prevent the most catastrophic effects of global warming.

But she noted that Brazil’s public statements don’t yet line up with its domestic policies and warned that the deal could be used by some countries to “greenwash” their image.

The Brazilian government has been eager to project itself as a responsible environmental steward in the wake of surging deforestation and fires in the Amazon rainforest and Pantanal wetlands that sparked global outrage and threats of divestment in recent years. But critics cautioned that Brazil’s promises should be viewed with skepticism, especially as Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro is an outspoken proponent of developing the Amazon.

About 130 world leaders are in Glasgow for what many scientists say is the last realistic chance to keep global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) above pre-industrial levels — the goal the world set in Paris six years ago.

Increased warming over coming decades would melt much of the planet’s ice, raise global sea levels and greatly increase the likelihood and intensity of extreme weather, scientists say.

As the COP26 climate summit begins, we know basically what we need to do to keep climate change from destroying us. So what’s the holdup?

On Monday, the leaders heard stark warnings from officials and activists alike about those dangers. Britain’s Johnson described global warming as “a doomsday device” strapped to humanity. United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres told his colleagues that humans are “digging our own graves.” And Barbados Prime Minister Mia Mottley, speaking for vulnerable island nations, warned leaders not to “allow the path of greed and selfishness to sow the seeds of our common destruction.”

Britain’s Queen Elizabeth II urged the leaders “to rise above the politics of the moment, and achieve true statesmanship.”

“Of course, the benefits of such actions will not be there to enjoy for all of us here today: We none of us will live forever,” she said in a video message played at a Monday evening reception in a Glasgow museum. “But we are doing this not for ourselves but for our children and our children’s children, and those who will follow in their footsteps.”

The 95-year-old monarch had planned to attend the meeting, but she had to cancel the trip after doctors said she should rest.

Breaking News

Get breaking news, investigations, analysis and more signature journalism from the Los Angeles Times in your inbox.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

The British government said Monday that it saw positive signs that world leaders understood the gravity of the situation. On Tuesday, President Biden is due to present his administration’s plan to reduce methane emissions, a potent greenhouse gas that contributes significantly to global warming. The announcement was part of a broader effort with the European Union and other nations to reduce overall methane emissions worldwide by 30% by 2030.

But campaigners say the world’s biggest carbon emitters, including the U.S. and China, need to do much more. Earth has already warmed 1.1 degrees Celsius (2 degrees Fahrenheit). Current projections based on planned emissions cuts over the next decade are for it to hit 2.7 Celsius (4.9 degrees Fahrenheit) by the year 2100.

Climate activist Greta Thunberg told a rally outside the high-security negotiations venue that the talk inside was just “blah blah blah” and would achieve little.

“Change is not going to come from inside there,” she told some of the thousands of protesters who have come to Glasgow to make their voices heard. “That is not leadership. This is leadership.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.