TUMBIRA, Brazil — By all measures, Giovane Garrido Mendonça should be a logger.

His father and grandfather and great-grandfather all made their livings felling thick trees deep in the Brazilian Amazon. As a child, Mendonça often tagged along, proudly toting his father’s chainsaw.

But Mendonça isn’t a logger. He’s a tour guide.

In 2008, the government turned hundreds of thousands of acres of rainforest surrounding the tiny community of Tumbira into a “sustainable development reserve.” To dissuade residents from razing the jungle, a nonprofit helped the village open an eco resort.

As wide swaths of the Amazon are clearcut or burned to clear land for cattle or agriculture, critically reducing the forest’s ability to absorb carbon from the atmosphere, Mendonça takes visitors on camping trips along the lush banks of the Rio Negro.

“I’m 24 years old,” he said. “And I’ve never cut down a single tree.”

In the world’s race to slow climate change, the success story in Tumbira represents the smallest of victories, demonstrating both what is possible and how far there is to go.

Such efforts won’t matter much unless a handful of countries — China, the United States, Japan, India and Brazil to name a few — take immediate action on a massive scale to dramatically slash their planet-warming carbon emissions.

Heads of state, environmental activists, business leaders and journalists are in Scotland for a climate summit that comes as world leaders are running out of time to break away from fossil fuels and prevent the most catastrophic effects of global warming.

That daunting task takes center stage Sunday when delegates from nearly 200 nations meet in Glasgow, Scotland, to commence the two-week United Nations climate summit known as COP26. Failure to reach a course-changing agreement could usher in the environmental calamity scientists have been warning about for years.

“We can either save our world or condemn humanity to a hellish future,” U.N. Secretary-General Antonio Guterres said in a tweet to COP26 delegates.

Unlike past conferences in Paris or Kyoto, Glasgow will take place when the effects of the crisis are being felt acutely.

In the Middle East, groundwater sources are being quickly depleted, causing neighborhoods in the Iranian capital of Tehran to begin sinking.

In Western Europe, more than 200 people died this summer after days of record rainfall triggered floods that swept away centuries-old villages.

And in the Pacific Northwest, a summer heat wave obliterated records for temperatures in the region and killed dozens of people.

Such extreme weather events are expected to become much more common if the temperature increase over preindustrial times surpasses 2.7 degrees — a threshold that scientists predict will be reached by 2030 under current trajectories.

More than 2 degrees of warming has already occurred. Holding the increase to 2.7 degrees would require curtailing global emissions by 55% over the next nine years — more than seven times the current pledges, according to the U.N. Environment Program.

Governments’ failure to take aggressive action looms large as leaders head to the COP26 climate summit, billed as “the last, best chance” to save Earth.

The COVID-19 pandemic gave the world a glimpse of the sort of annual reductions that are needed. Emissions fell 6.4% in 2020 after swaths of industry and most international travel came to a halt.

But fossil fuel consumption has since rebounded — so much so that the International Energy Agency estimates that by the end of this year, emissions will approach 2019 levels.

U.S. climate envoy John Kerry called the summit the “the last, best chance” to stave off catastrophe.

To reverse course, world leaders in Scotland must agree to the steepest emissions cuts ever at a time when economies are faltering, geopolitical tensions are rising and a once-in-a-lifetime pandemic drags on.

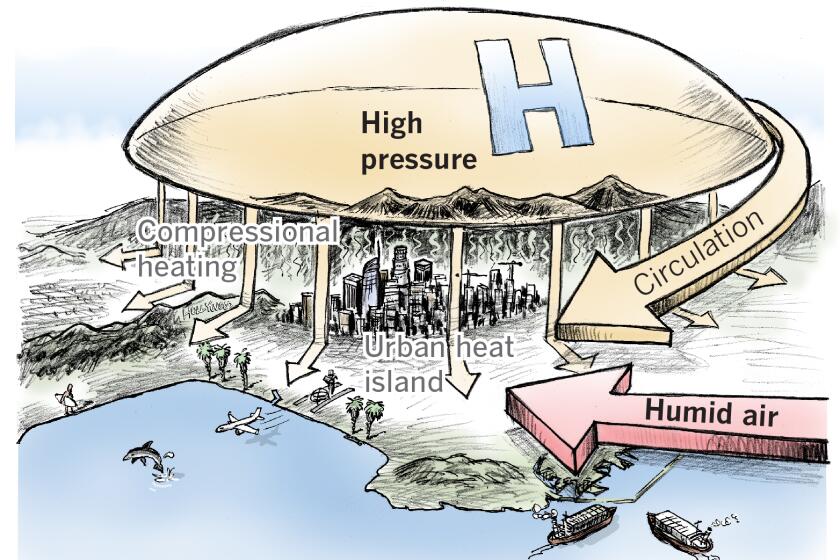

California’s worst heat waves arrive in a one-two punch — high temperatures combined with humid air from Baja.

To measure progress, nations are being asked to put forth so-called nationally determined contributions that enhance pledges to reduce emissions made in Paris six years ago.

Leading the charge among developed nations are Britain and the United States. Using 2005 emissions as a baseline, they are aiming for cuts of at least 63% and 52%, respectively. Actual reductions now stand at 28% and 12%.

Challenges abound. At home, President Biden is struggling to enact the full scope of his climate agenda in a Congress where roughly a quarter of members deny the existence of human-caused global warming. British Prime Minister Boris Johnson has been criticized for not providing a more detailed roadmap to achieve his nation’s targets.

The European Union aims to reduce carbon pollutants 51% below 2005 levels — they are currently at 29% — but the continued influence of industry has impeded faster change. Prominent environmental activists such as Sweden’s Greta Thunberg have accused European leaders and major corporations of exaggerating their environmental commitments.

The accusation has particular resonance in Germany, Europe’s largest economy. Despite billing itself as a green leader, the country remains a major coal user. And in a burgeoning era of electric vehicles, car emissions there rose 6% over the last decade — a reflection of the powerful auto lobby that has blocked calls to impose speed limits on the nation’s famed Autobahn.

“There’s a huge dissonance between who we think we are and who we are,” said Luisa Neubauer, a prominent German climate activist.

In Japan and South Korea, two of the world’s largest polluters, entrenched business interests such as nationalized power companies are resistant to renewable energy.

No country has a bigger influence on climate change than China, which according to the International Energy Agency was responsible for 29% of global emissions in 2019.

It released as much carbon into the atmosphere as the next four biggest polluters combined — with 14% of emissions coming from the United States, 7% from India, 5% from Russia and 3% from Japan.

China is simultaneously the globe’s largest market for electric vehicles, the largest user of wind and solar energy and the leading consumer of coal — highlighted by the recent scramble to source more of the dirty fossil fuel amid a recent energy crisis.

Leaders of China say its carbon emissions will rise until 2030, then decline over the next three decades until the country reaches carbon neutrality — meaning it will offset all the emissions it produces by funding reductions elsewhere. Details remain scant.

Growing friction between China and the United States has undermined cooperation between the world’s top two polluters. Unlike Biden, Chinese President Xi Jinping has announced he won’t be attending the Glasgow summit.

Climate change is making the world more prone to floods like those in China and Europe and to heat waves and fires like those in the U.S. and Russia.

China has long argued it was a developing country and should not have to adhere to the emissions cuts expected of the West, which is responsible for most of the world’s pollution historically — a posture echoed by India. On a per capita basis, the United States pollutes twice as much as China and eight-and-a-half times as much as India.

Another possible no-show in Glasgow is Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, who hasn’t confirmed yet whether he will be joining his country’s delegation.

Though Brazil doesn’t rank among the top 10 biggest emitters, it remains a linchpin in efforts to fight climate change because more than half the Amazon lies within its borders. The rainforest has long been one of the world’s most important carbon sinks, absorbing about 5% of the 40 billion metric tons of carbon emitted into the atmosphere globally each year.

But the rainforest is losing that ability as trees are cleared. In a study published in Nature last summer, scientists found that large parts of the Amazon — especially in the heavily deforested southeast — now emit more carbon than they absorb.

In places such as Rumo Certo, an informal settlement three hours north of the city of Manaus, development has exploded, with wide swaths of forest replaced by highways, housing and cattle farms.

When teacher Francisco Cleiton Siqueira Mesquita moved there in 2001, paying $75 for a recently cleared lot, there were only about 40 homes. Now there are more than 700. The same thing is happening across the region, he said: “Every six months a new community is born here.”

Siqueira said he feels uneasy about the growth, which he knows is bad for the planet.

“We need to protect the Amazon,” he said. “But most people, they’re thinking about survival.”

“I’m not judging others,” he said. “I also came here for opportunity.”

Widespread destruction of the jungle has sparked dryer, hotter weather, which could soon turn most of the Amazon into a savanna, dramatically altering weather patterns throughout South America.

The problem has worsened significantly under Bolsonaro, a right-wing populist who took power in 2019 and immediately began loosening environmental regulations.

He and many of his supporters have embraced a provocative argument: If you want us to stop deforesting the Amazon, pay us.

His former environmental minister, Ricardo Salles — ousted earlier this year over his alleged links to illegal timber smuggling — said that the country could lower deforestation by up to 40% if it received $1 billion in foreign aid.

The rest of the world may suffer the consequences if the U.S. and China don’t work together on reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Hamilton Mourao, Brazil’s vice president, told journalists this week that the delegation in Glasgow will pursue a similar demand.

“The Amazon represents around 50% of Brazil’s territory,” he said. “We’re talking about preserving 10 Germanys.”

There’s no doubt that changing course in the Amazon and the rest of the world often comes with a high upfront cost.

In Tumbira, the transformation from logging community to eco resort probably wouldn’t have happened if it wasn’t for the Foundation for Amazon Sustainability, the nonprofit that invested heavily there, and whose projects are partly funded by major corporations such as Procter & Gamble and Samsung.

Questions of long-term sustainability remain. During the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic, tourism dried up. With no income save a small stipend from the nonprofit, Mendonça’s father, Roberto Brito de Mendonça, said he thought about returning to logging to feed his family.

Luckily, business picked back up again.

On a recent afternoon, two tourists — cousins from Sao Paulo — sunned on a wooden pier after bathing in the Rio Negro.

One of them was Camila Firmano Drummond, 29, who works for a company that makes wind turbines. She had never been to the Amazon before, and said she visited with an intention: “There was a bit of a feeling of wanting to see it before it disappears.”

Linthicum reported from Tumbira, Pierson from Singapore. Times staff writers Nabih Bulos in Beirut, Victoria Kim in Seoul, Alice Su in Beijing and special correspondents Erik Kirschbaum in Berlin and Ana Ionova in Tumbira contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.