Column: Global warming policies in Biden’s budget bill are in trouble. Here’s what they are and why they’re crucial

The headline news about the global warming provisions of the big budget bill being negotiated in Washington is that they’re in trouble.

As has been the case with the safety net provisions of the bill, the news coverage has focused on process rather than substance.

It has focused on the obstinacy of Sen. Joe Manchin III (D-W.Va.), who seems determined to protect his state’s moribund coal industry (from which he collects lots of personal income).

Not enough has been written about what’s actually in the bill and how it would help the U.S. reach its goals for reducing global warming.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

So in this follow-up to my earlier report on the social welfare provisions of the reconciliation package — so dubbed because it’s expected to be passed by filibuster-exempt budget reconciliation rules — I’ll provide details of the key environmental provisions of the bill.

First, some context. The clean energy provisions of the budget bill, which envisions spending $3.5 trillion over 10 years, are essential for meeting President Biden’s goal of reducing America’s greenhouse gas emissions by more than 50% from 2005 levels, with a deadline of 2030.

Biden hopes to have a package in hand when he travels to Glasgow, Scotland, for an international summit on global warming on Nov. 1 and 2. He’s also determined to reverse four years of inaction — indeed, sabotage — on climate initiatives under the Trump administration.

The reconciliation package, which congressional Democrats hope to pass in time for Glasgow, may be Biden’s best chance to show progress. It won’t be his last or only chance, however.

The fossil fuel industry claims ‘renewable natural gas’ is green. It isn’t.

Much of what Biden hopes to achieve can be done within the framework of existing laws, which Trump simply ignored or attempted to undermine. Ending that approach will improve America’s position in the fight against global warming all by itself.

The reconciliation package, however, encompasses new, proactive elements. So let’s review the key pieces.

Clean electricity

The Clean Electricity Performance Program is one of the two most important provisions in the bill in terms of reducing greenhouse gases. Senate Majority Leader Charles E. Schumer (D-N.Y.) told colleagues in an Aug. 25 letter that this provision and electric vehicle rebates together account for two-thirds of the emission reductions in the entire bill.

Under the program, utilities that increase their output of clean energy by 4% over the previous year would receive grants of roughly $150 per megawatt-hour of improvement between 2023 and 2030, though the actual calculation is a bit more complicated. (The average residential consumption nationwide comes to about 11 megawatt-hours per year.)

Clean energy is defined in the bill in a way that excludes fossil fuels such as oil, gas and coal, leaving chiefly renewable sources such as solar, wind and hydro power.

This would be a strong incentive for utilities to step up their conversion to clean generation sources, especially since it would be paired with a penalty of $40 per megawatt-hour by which they miss the 4% goal. Utilities that have reached 85% clean energy would be exempt from the penalty, as long as their percentage of clean generation doesn’t fall from the prior year.

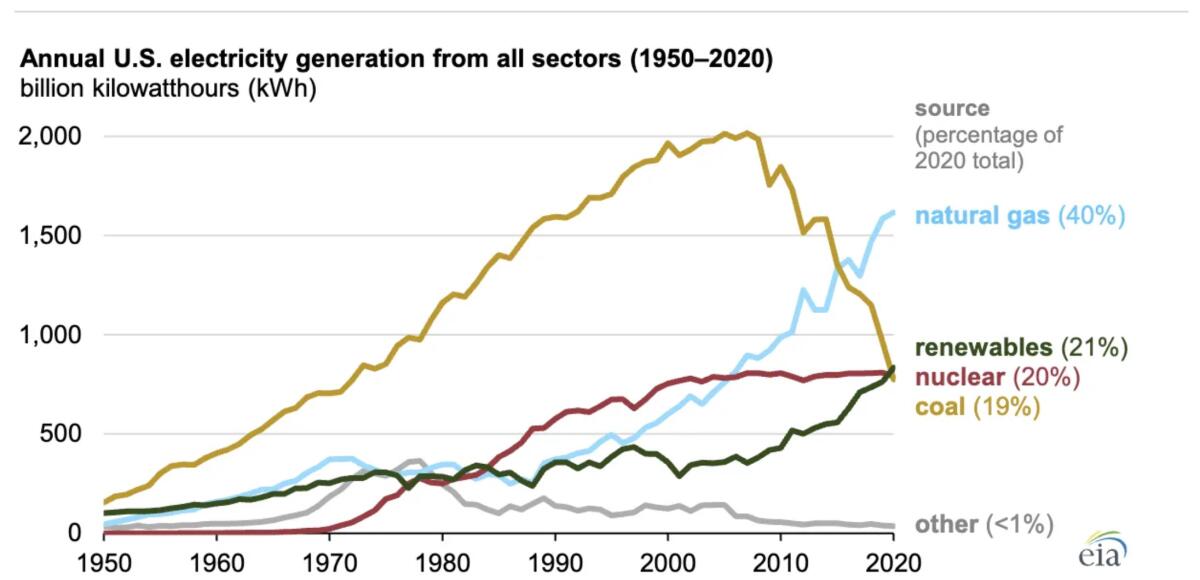

The utility industry has a ways to go before reaching that mark — in 2020, only 21% of U.S. energy generation came from low-carbon sources including renewables and nuclear.

This is evidently the provision that most sticks in Manchin’s craw. Not only does he represent the nation’s second-largest coal-producing state (after Wyoming), but he collects roughly a half-million dollars per year in compensation from a coal brokerage he founded and has left to his son to operate.

Manchin probably knows this, but someone ought to remind him that the coal economy is dead. Coal in 2020 accounted for about 19% of U.S. electrical generation and is plummeting; as recently as 2007 it was the nation’s largest electrical generating source, with about a 48% share.

Manchin has about as much of a chance of saving the coal industry through his stubbornness as the legendary King Canute had of commanding the tide to recede. Coal industry employment reflects reality: It’s down to about 42,000 workers, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, from more than 177,000 in 1985.

Corporations of all kinds are getting an earful from shareholders and the SEC about the need to disclose climate change impacts.

The Clean Electricity initiative, on the other hand, would produce more than 7 million new jobs over the next 10 years and add more than $900 billion to the economy in that time, according to an analysis sponsored by the Natural Resources Defense Council.

Leaks from Capitol Hill over the weekend suggested that Manchin is angling for some variety of giveaways to coal and oil and gas producers in the bill, perhaps by granting incentives to coal plants equipped with carbon capture technology. If that’s what it takes to get this crucial measure into law, one supposes that it’s a modest price to pay.

Electric vehicles

The measure would provide $19 billion in grants and incentives to encourage the rollout of electric vehicles. That would include $3 billion in rebates for equipment such as public chargers, of which $1 billion would be designated for low-income areas.

This sort of infrastructure is the missing element in a chicken-and-egg conundrum in the electrification process of the transportation sector. People may be reluctant to buy electric vehicles if they can’t be certain of finding places to charge them whenever needed.

California alone needs more than 60,000 new charging stations by 2025 as it moves toward its goal of banning the sale of new gasoline-powered cars as of 2035, according to the Sierra Club. More than 150,000 stations are needed by 2030 to meet the state’s goal of electrifying medium- and heavy-duty vehicles.

As it happens, the reconciliation package would include $5 billion in grants and rebates to convert trucks to electricity. The program would cover medium-duty vehicles such as commercial trucks and school buses, and heavy-duty vehicles such as garbage trucks, city buses and big rigs with three axles or more.

Joe Biden’s election points to historic gains in the fight against climate change.

These programs are indispensable elements in the fight against climate change because the transportation sector, which accounts for 29% of greenhouse gas emissions, is the single biggest contributor to those emissions in the U.S.

Home retrofits

The bill would provide $9 billion through 2031 for home conversions to energy-efficient and electric systems. The sum includes $500 million to train contractors. The eligible work would include energy-efficient home heating, ventilation and air-conditioning, insulation installation and advanced efficiency technologies.

Public buildings and electrical infrastructure

The bill includes $3.2 billion for efficiency and electrification upgrades for local public buildings and those housing nonprofits, as well as $17.5 billion for upgrades to federal buildings. An additional $9 billion would be made available for upgrades to the national electric grid to make it suitable for the changes in electricity demand triggered by building upgrades and vehicle electrification.

The reconciliation package isn’t the only global warming legislation being pondered by congressional Democrats. The Clean Energy for America Act, largely developed by Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) and passed in May by the Senate Finance Committee, would consolidate and extend tax credits for electric vehicles and eliminate more than a dozen tax breaks long enjoyed by the fossil fuel industry.

The urgency of passing many of these programs now isn’t just a matter of political bragging rights. The consequences of global warming have never been as vivid as they have become over the last year, given intensively destructive storms, the swamping of low-lying properties thanks to the sea-level rise, temperature extremes across the U.S. and the world, and earlier and longer wildfire seasons on the West Coast.

The indications are inescapable that the bill for decades of heedless human activity is coming due. The provisions in the reconciliation bill are merely a preliminary down payment. Inadequate as they are, they’re at least a start. Stiffing the climate again would be inexcusable.

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.