Kidnapping, extortion and OnlyFans: How a mother escaped a gangster’s plot

The store in Jurupa Valley displayed dresses, blouses and shape-wear. In a back room were gambling machines, a striptease pole and a bathroom where a woman told authorities she had been locked up for days under threat of being forced to film videos for OnlyFans, the subscription-based pornography service.

According to documents filed in federal court in May, the shop was controlled by a local gang, Westside Riva. The case suggests that some criminal groups have attempted to add pornography and gambling to their more traditional revenue streams of selling drugs and collecting “rent” from narcotics dealers.

Authorities arrested a suspect last week in the death of Eduardo “Eddie Boy” Castro, a Mexican Mafia member who was gunned down five years ago while riding a bicycle in Boyle Heights.

The woman, identified as “Jane Doe” and “Person 1” in court documents, said she was abducted after police seized money that allegedly belonged to Luis Ramirez, an inmate at California State Prison, Solano.

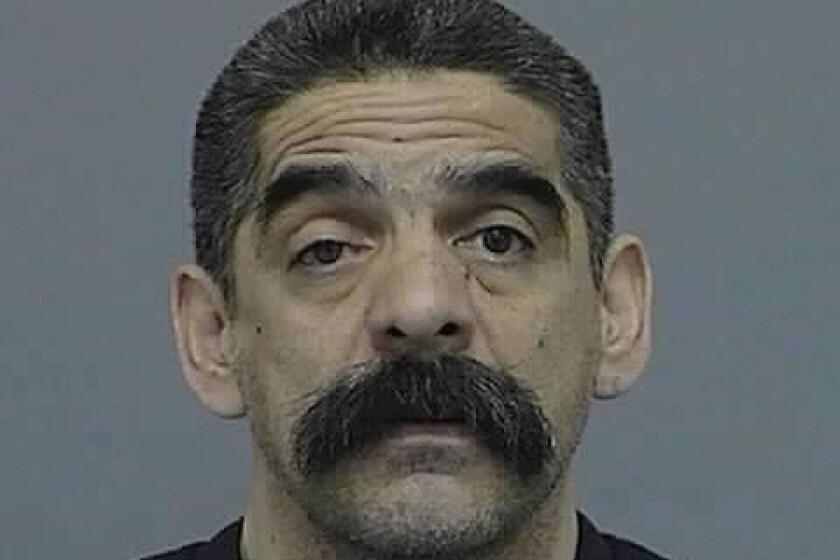

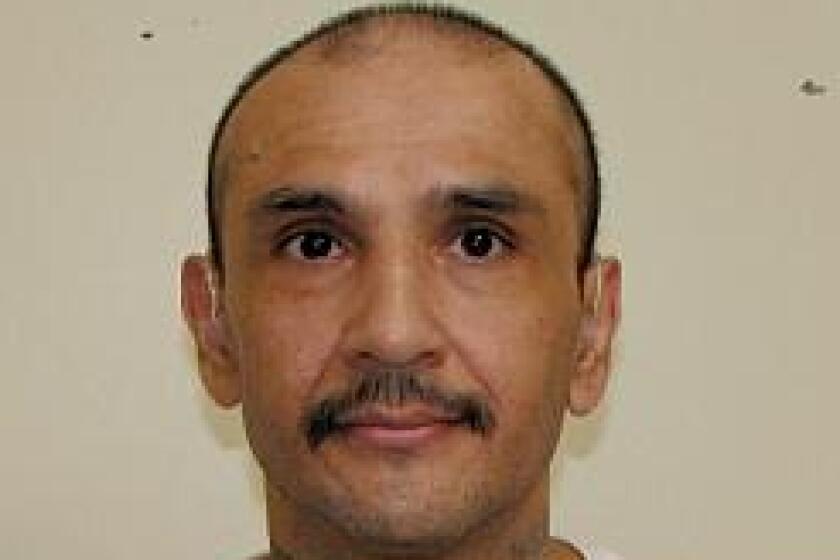

Ramirez, 47, and two others have pleaded not guilty to kidnapping, extortion and violent crimes in aid of racketeering. Ramirez’s attorney, Carlos Juarez, declined to comment.

Although he hasn’t walked the streets of Jurupa Valley — a city on the western fringe of Riverside County — in three decades, authorities allege he had been collecting thousands of dollars a week in protection payments from local businesses.

Subscribers get exclusive access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers special access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Explore more Subscriber Exclusive content.

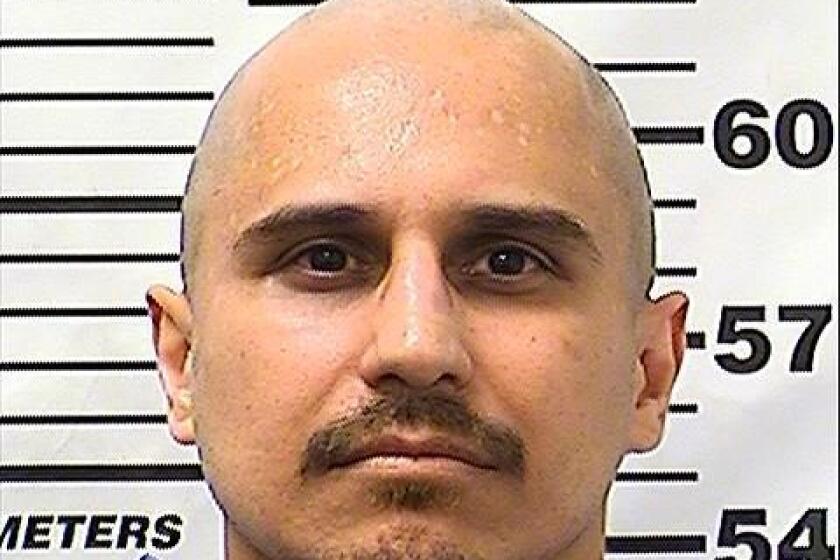

When Jane Doe lost his money, prosecutors charged, Ramirez used a contraband cellphone to order a 21-year-old member of his old street gang to abduct her. Jose Jonathan Rubalcaba Alarcon told authorities he eventually set the woman free after Ramirez told him to do “grimy s—” to her.

“That m—f— is evil,” he said of Ramirez, according to an FBI agent’s affidavit. “I’m just going to tell you, I thought I was evil. He’s a lifer. They don’t give a f— about nobody, and I found out the hard way.”

::

The cashier was panicked.

“There’s three guys hanging out at the front,” she told the owner of a Jurupa Valley gas station in a voice message in September. “Look at the camera, please.”

Rubalcaba had been there the day earlier, demanding that the owner pay a “protection” fee for the right to sell credits used for illegal gambling apps such as RiverSweeps, FireKirin, SkillMine and VegasX, according to an FBI affidavit and search warrants reviewed by The Times.

These apps, which gamblers sometimes call “software,” represent a growing source of revenue for the Mexican Mafia, a syndicate of about 140 prisoners that controls Latino gangs in Southern California. Last year, authorities wrote in a search warrant affidavit that they intercepted a call in which one Mexican Mafia associate lectured another who had complained of being broke: “I told you where it’s at — it’s software and drugs.”

The owner of the Jurupa Valley gas station had balked at paying for protection, saying his customers weren’t gambling much. Rubalcaba promised to come back, according to the FBI affidavit.

“I got my boss right here on the line,” he told the cashier the next day, holding out a phone. “He’s pretty upset.”

In a jailhouse interview, reputed Mexican Mafia boss Johnny Martinez says he is an innocent man being railroaded by lying witnesses and vindictive prosecutors.

A Riverside County sheriff’s deputy, responding to a 911 call from the gas station owner about a suspicious person, walked in and detained Rubalcaba, who was later released.

Reviewing surveillance footage, FBI agent Benjamin Beck wrote in the affidavit, authorities saw Rubalcaba had arrived in a black Cadillac CTS. Later that night, deputies stopped a similar car on Mission Boulevard.

Sitting in the backseat was Jane Doe. She had $7,247 in her purse. Believing it came from extortion, deputies seized the money.

::

Jane Doe told the authorities she had met Rubalcaba several months earlier at a casita, an illegal gambling parlor where patrons can play electronic games of chance. In recent years, the Mexican Mafia has muscled into gambling rackets either by “taxing” independent casitas within their territory or opening gambling dens of their own.

Rubalcaba proposed doing “business” with Jane Doe, who said she knew this meant paying to protect her store in Jurupa Valley.

Casitas represent ‘more than just gambling,’ says a Los Angeles sheriff’s detective. ‘It’s extortion, it’s murder, it’s assault.’

After she refused, she said, she was beaten by a woman at a bar in Riverside. Rubalcaba walked in a few minutes later.

“You want protection now?” he asked, according to Jane Doe.

He introduced her over the phone to Ramirez, and she began paying $300 a month, a sheriff’s deputy wrote in an affidavit.

Jane Doe said Ramirez made her expose herself on camera and posted her photograph on a swingers’ website.

It was Ramirez’s money she was carrying when pulled over in the Cadillac, she told deputies. According to Jane Doe, Ramirez said if she didn’t get it back, he would “take something away from her that she will remember for the rest of her life.”

She believed he was referring to her daughters.

The syndicate once relied on associates on the streets, but court data showed that smuggled phones have given imprisoned leaders greater control over drug deals.

Ramirez was, by his own admission, a “ticking time bomb” when he went to prison in 1995 at 18. Convicted of attempting to murder three men, he was sentenced to three consecutive life terms.

“That’s more than the Unabomber,” he told the parole board in 2015. “And I didn’t even kill no one. So yes, I did feel angry. I felt I had been done unjustly.”

At that point, he said, “I figured, why even try to be good?”

He said he set his mind to become “just the worst I could be and make my way to Pelican Bay” — the maximum security prison where many Mexican Mafia members were then held. Found guilty of attempting to murder an inmate, Ramirez was sent in 2004 to Pelican Bay’s Security Housing Unit, where inmates spend 23 hours a day in isolation.

Ramirez denied to the parole board being affiliated with the Mexican Mafia.

Until his murder in prison two weeks ago, Michael Torres ran one of the most intricate and lucrative black market businesses in L.A. County: the jails.

A psychologist who evaluated Ramirez described him as a narcissist.

“He has made repeated efforts to contact influential people in an effort to have his memoirs published or somehow made into a screenplay,” the doctor wrote.

::

Ramirez’s path to prison began in childhood.

With his father in jail and his mother in and out of state mental institutions, according to parole records, he was separated from his siblings and raised in foster homes until his grandmother took custody of him.

Ramirez said his grandmother lived in the “worst of the worst” neighborhood in South Los Angeles, so he moved with his mother to Jurupa Valley.

A former land grant rancho, Jurupa Valley is filled with sun-beaten single-family homes and trailer parks, not far from a rock quarry listed as a federal Superfund site. Some of its roads are still not paved. Broken-down cars dot front yards and alleyways.

Ramirez told the board he hung around a neighbor from Westside Riva. The 13-year-old found his South Los Angeles roots gave him cachet.

“All these blockbuster movies came out. Menace to Society, South Central, Colors,” he told the board. “I didn’t even know I was from South Central until these guys started telling me, ‘Oh, so you’re a kid from South Central?’ So that kind of boosted up my ego.”

The past caught up to Donald Ramon Ortiz the afternoon of Nov. 19, 2021. It came disguised as a detective, holding a gun in a gloved hand.

Ramirez took the nickname “Little Man.” By 14, he was living on his own, he said, supporting himself — and a PCP addiction — by working at a car wash and stealing vehicles.

Three years later, in 1994, Ramirez committed the crimes that sent him to prison for life. He shot three men in the darkened parking lot of a fast food restaurant after demanding to know where they were from.

“I was a 17-year-old gang member trying to prove myself and make a name for myself,” he told the board.

Although a generation younger, the allure of Westside Riva was much the same for Rubalcaba. The younger man started calling himself “Demon.”

According to Beck’s affidavit, he told sheriff’s deputies he wanted to be seen in the neighborhood as a “big ‘ole killer, robber.” Instead, he found himself taking orders from a man he’d never met.

Every month Rubalcaba had to pay Ramirez $5,000, money he collected from gas stations and smoke shops, he said. He said he sent the money over J-Pay, a money transfer system for state prisoners. Ramirez trusted him so little, Rubalcaba said, he demanded that he count the money on camera.

Rubalcaba’s lawyer didn’t return a request for comment.

After Jane Doe lost the $7,000, Rubalcaba put Ramirez on speakerphone, she told sheriff’s deputies.

“That b— better get my money,” Ramirez allegedly said.

The woman said Rubalcaba took her to a Walmart to purchase an air mattress before driving her to a store called Rubidoux Fashion. She told authorities Ramirez planned to have her perform sex acts for paying customers on OnlyFans.

The facade of Rubidoux Fashion is painted with a bell and the words Ropa Para Mujeres. Today, a padlocked chain is wrapped around the door handles. Metal bars cover the windows.

She admitted falling for a man whose embrace she had never known, who lived his days in what he called ‘paseo de la muerte.’ Death row.

Authorities suspect Ramirez had controlled Rubidoux Fashion since at least 2021, when guards seized a cellphone from him that contained photographs of the business, Beck wrote.

In its back room was a memorial to Braulio “Babo” Castellanos, a well-known Mexican Mafia member and longtime leader of the Florencia-13 gang. Castellanos was imprisoned with Ramirez until he was granted a compassionate release last year shortly before his death from cancer.

After bringing Jane Doe to the shop, Rubalcaba called Ramirez and put him on speakerphone. “Strip her down, take her s— and lock her up,” Ramirez said, according to the FBI affidavit.

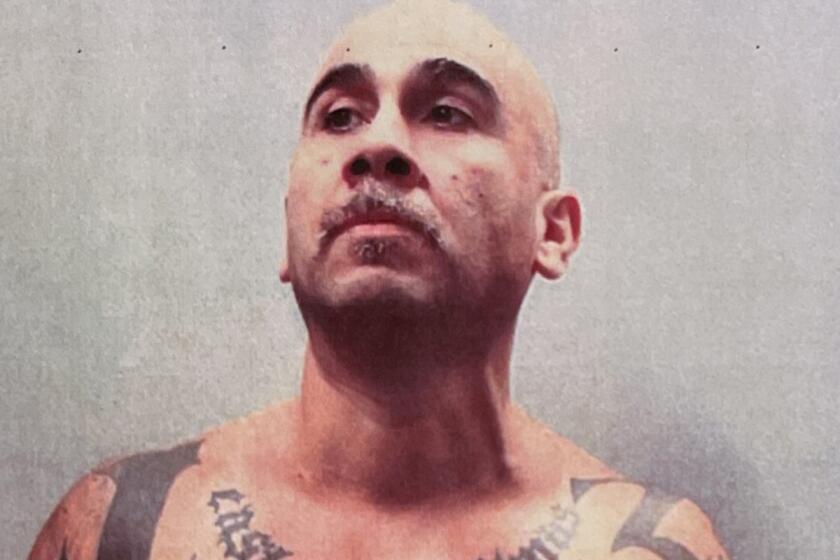

She said Rubalcaba took her phones but didn’t remove her clothes. Another man, Gilbert “Bam Bam” Martinez, 20, struck her in the stomach, pushed her into a bathroom and locked her inside, she said.

Martinez’s lawyer didn’t return a request for comment.

Jane Doe remained there for four days, according to the FBI affidavit. Rubalcaba and Martinez returned each day to let her out of the bathroom, she told sheriff’s deputies. She ate some candy lying around the store, drank a beer left inside a fridge and water from the bathroom sink.

On the fourth day, Rubalcaba told Jane Doe he’d been ordered to beat her. Instead, he walked away and left the bathroom door unlocked.

Prosecutors suspect a powerful prison gang was behind the mysterious killings of two men with ties to Russian and Israeli organized crime.

Jane Doe said she fell asleep on the bathroom floor. She woke up and opened the door. A camera had been set up in the hallway. She said she heard Ramirez’s voice coming from a speaker. She ignored his orders to go back into the bathroom, scaling a chain-link fence with the help of a bystander who tossed over a tire that she used for a boost.

After interviewing Jane Doe at a hospital, sheriff’s deputies raided Rubidoux Fashion. Rubalcaba, who watched the search from a PT Cruiser parked down the street, was arrested at the scene. According to Beck’s affidavit, Rubalcaba said he kidnapped the woman on Ramirez’s orders.

“He wants me to put her butt naked, tie her up, take all her s—,” Rubalcaba said. All he did, he claimed, was take Jane Doe’s phones and tell her, “Just chill and talk to him and everything’s going to be fine.”

Rubalcaba told the deputies he was relieved to be arrested.

“At the end of the day, we all sign up for some s— and sometimes you end up regretting it,” he said. “You try to find a way out, but there is no way out.”

More to Read

Subscriber Exclusive Alert

If you're an L.A. Times subscriber, you can sign up to get alerts about early or entirely exclusive content.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.