The sparrows fled the courtyard. It was quiet amid the classics. John Szabo stepped out of the elevator and walked through the sunlit atrium of the Central Library. He passed a slumbering homeless man and, with the efficiency of a spy, disappeared into stacks of bound archives, hundreds of thousands of relevant and obscure pages — including the 1991 “Journal of the American Chamber of Commerce in Japan.”

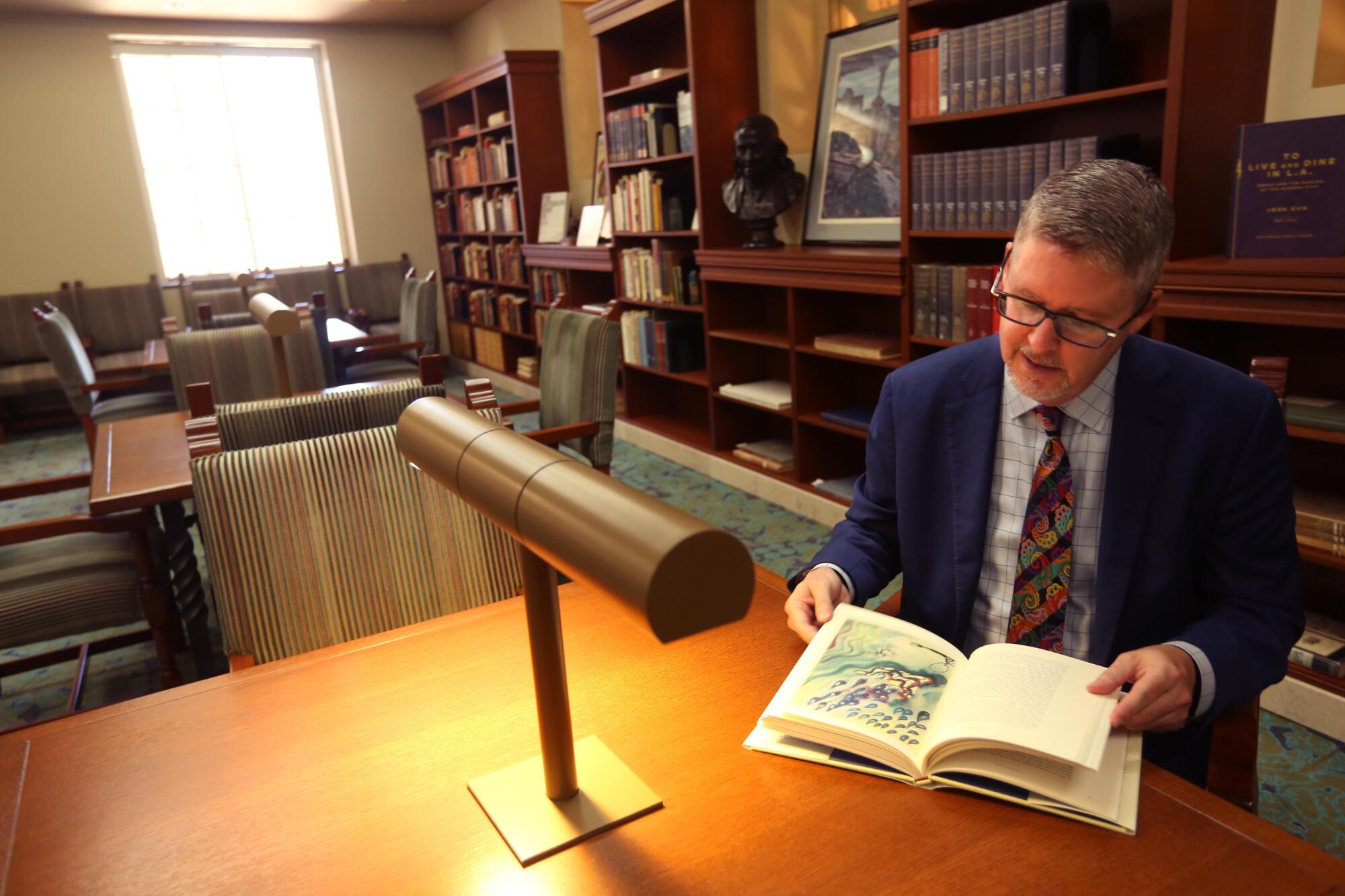

A tall man with sparks of gray in his goatee, Szabo, the city librarian, oversees 72 branches, a $241.8 million budget, 17,000 restaurant menus, 64 ukuleles, a Shakespeare volume from 1685, and lockers of puppets for a children’s theater. He stopped at a shelf holding years of “Family Handyman” magazines. Founded in 1951 for those who grout tile and hang cabinets, the periodical was no match for Prince Harry’s memoir or a Stephen King novel.

“How often does this get requested?” said Szabo, who calculates the future in centimeters and paragraphs and recently read a book about how U.S. states got their shapes. “I don’t want to lose it, but this is valuable space. These are the things I think about. How to fit it all together.”

The Los Angeles Public Library’s mission has dramatically expanded since it was founded in 1872 with 500 books for a “bustling pueblo” of 6,000 people. Today, it has more than 8 million books and serves the largest and most diverse urban population of any library system in the country.

It rides the cusp of technological change with e-books, artificial intelligence, trained computer “cybernauts” and 7,000 loanable Tech2go backpack bundles complete with laptops and hotspot connections. The library’s futuristic 3D printing Octavia Lab, named for science fiction writer Octavia Butler, made protective face shields for hospitals in the early days of the pandemic.

The library is at once a sanctuary of the world’s knowledge and a canvas of a nation’s failings.

“We are a reflection of our neighborhoods,” said Karen Pickard-Four, who coordinates security and social services at the Central Library and all the branches. “When did we as a society stop caring about the less fortunate?” she asked. “There’s no middle class. It’s the haves and have-nots. That’s why people are sleeping here during the day.”

Homeless people shoot up and wash in library bathrooms, belongings piled at their feet. Those with mental illnesses murmur among Homer, Virgil and Aristotle. Addicts sit slack-eyed amid foreign language books and a bust of Gibran Khalil Gibran. Over the last eight months, 435 of the library’s staff of nearly 1,200 have undergone Narcan training, and at least six drug overdose victims have been revived on library property. Social worker Edna Osepans was recently hired at the Central Library to tend to agitated patrons beneath the pastel-toned murals of Westward colonization that shine in the rotunda.

“It’s about how we adjust to the new reality,” said Joyce Cooper, director of branch library services, who is partial to Irish stories and romance novels. “People have been predicting the demise of the [American] library for years but we keep adapting.”

Librarians can tell you about the turn of a page or the mystery of sentence. But they are on the front lines of a world they seldom imagined. They can track down a wayward book one moment and console someone with schizophrenia the next. They have panic buttons at their desks, undergo stress management, and thumb through “A Trauma-Informed Framework for Supporting Patrons,” a guide on how to deal with drug abuse, adult-self neglect, child abuse, panhandling, stealing, threatening behavior and “persons with strong personal odor.”

“We say yes to a lot of things,” Szabo said. “It’s about how we define what the library is. I love the fact that people can see the library as part of a solution to a community issue. But how much social work is enough? How much public health programming is enough? How far do we go with adult education?”

The mission of the library is to serve all Angelenos, a creed that, although tested at times, begins with Szabo and radiates through its branches. It is, as one librarian put it, a place where John Lithgow can be found reading next to an unhoused person in the North Hollywood branch.

Libraries across the nation are encountering poverty, mental illness and homelessness — forces that have led to staffing and morale problems as the institutions confront increasing pressures. The Los Angeles Public Library — security is run by the LAPD and library guards — can at times feel like a surreal other world: men stalking young female shelvers, a man with weeping gangrene, seizures in hallways and, in recent years, a fatal overdose and the death of person who jumped three stories from the literature department into the atrium.

In 2019, the Central Library and its branches reported 1,581 security incidents, including 107 assaults and 816 disorderly conducts. Incidents dropped in 2020 during the pandemic, but picked up again in 2022 with a total of 1,362, including 66 assaults and 778 disorderly conducts. Last year’s uptick in security violations came even as overall library attendance has dropped significantly from prepandemic times, from more than 10 million visits in fiscal year 2018-19 to 3.6 million in fiscal year 2021-22. Visits passed 4.5 million this past fiscal year.

The library, which has long been one of the city’s most respected institutions, embodies the complexities, joys, possibilities and sadness of Los Angeles. Most of its patrons are not homeless or mentally ill. They are like the boy who stood at the checkout counter with his parents and a bag of books as others spoke of novels and philosophy while downstairs a man read about the cerebral cortex and another sat before volumes on Colorado and the Inland Empire.

“I meet different people in different ways all the time,” said Pearl Yonezawa, branch manager in Los Feliz. “I didn’t know what the ‘golden ratio’ was in mathematics but someone came in and I looked it up. I learn something everyday. Questions on recipes and guacamole. One of my staff can talk to people about avocado trees.”

It is all Szabo’s domain. A son of the South, he is a raconteur who would fit more easily into a nostalgic short story by Truman Capote than into the pages of Faulkner. One might find him at an antiquarian books festival or in his office discussing “digital inclusion.” He is a multitude of facts and asides; he recently lowered his voice and nodded toward a plaque in the rotunda of Rufus B. Von KleinSmid, library commissioner and a leader in the eugenics movement who died in 1964.

“This will quietly come down,” he said.

On one floor, Szabo can show off 12,500 photos of Hollywood celebrities taken by a little-known photographer — for which the library paid $144,000 at auction — and on another disappear into rows of rare books and maps. He can tell you about the path to citizenship through the library’s New Americans Initiative, and a moment later mention that Mary E. Foy, the city’s first woman head librarian, who served from 1880 to 1884 and earned $72 a month, was a leading member of the women’s suffrage movement.

On an overcast afternoon, Szabo, 56, drove to the Chinatown Branch and mused about the cost of decarbonization, solar panels, air conditioning and carpets. His mind was like a juggler’s hands — moving and anticipating. “We need big projects to get us into the 21st century,” he said. Passing Disney Hall, he mentioned that Mayor Karen Bass “recognizes the multiple ways the library is stepping forward on homelessness.” He paused and noted: “Electrical outlets are a social service issue. Those without homes come to the library to charge their phones. They fight over them.”

He parked, got out of his car and slipped on a sports jacket.

“This railing needs painting,” he said, walking into the branch, where he was greeted by senior librarian Juanita Carter and Lynn Nguyen, the daughter of Vietnamese boat people who this year was named one of Library Journal’s “Movers and Shakers.” She was recognized for a community outreach program that collaborates with Asian farmers, more than 250 teenagers and Asian American and Pacific Islander organizations to deliver produce to 100 Chinatown residents every month. The project began after Chinatown’s last Asian grocery store closed amid gentrification.

She also helps students get financial aid for college, including about 18 a year who each receive a $3,000 scholarship from Friends of the Chinatown Library.

Nguyen is emblematic of how libraries are reaching further into their communities to increase cardholders and deal with changes that are forcing libraries, like schools and hospitals, to navigate a new America. At the Lake View Terrace Branch, where a chicken named Ozzie lived in the courtyard for five years until it was killed by a snake, senior librarian Constance Dosch worked for months as a contact tracer during the pandemic. She is now helping a homeless man find shelter and displaying an earthworm project to teach young readers about nature and the environment.

“Worms, chickens, free toothbrushes and deodorant for teens, and helping someone find new clothes,” Szabo said. “We meet people’s needs.”

He reached into his coat pocket and pulled out a map listing all 72 branches spread out over 503 square miles. When Szabo was hired in 2012, it took him more than a year to visit each one, journeys that led him across the diverse geography and demographics of his new home. While sitting in the parking lot of the Chinatown branch, he checked the map and drove to Boyle Heights.

He parked down the street from a bungalow — painted to look like a library card — that acts as temporary Benjamin Franklin Branch until $6.4 million in renovations are finished on the main building. Mariachi music played from a radio and a woman was selling clothes draped over a nearby fence. Inside, senior librarian Lupita Leyva, who came to the library decades ago as a kindergartner to learn English, waved as a girl entered with “Justice” emblazoned on her backpack.

Leyva works with a team to translate English materials into Spanish. More than 200 languages are spoken in Los Angeles; the library actively collects books in about 15 languages, including Japanese, Chinese, Armenian and Korean. Language is a testament to both legacy and change in Boyle Heights; many of those who came to the branch in the 1940s spoke Yiddish; now 85% speak Spanish. Leyva helps produce videos; she calls them “mini-telenovellas,” in which librarians act out skits that explain library services and community programs.

“We need to get to the larger Spanish-speaking community,” said Leyva, a swift woman with hoop earrings and pale pink tennis shoes. “You assume Boyle Heights has a lot of Spanish speakers, but neighborhoods are changing and now you have a growing number of Spanish speakers in places like Vernon. There’s a lot of bilingual people in Los Angeles and we have to serve that community.”

Driving back to his office in the Central Library, Szabo spoke of the intricacies of funding and the library’s civic and private partnerships, including the Library Foundation of Los Angeles, which supports a number of programs, including adult literacy, digitization and collections, and ALOUD, a renowned speaker program that draws in some of today’s best authors and novelists. He parked and took the elevator up.

In 1986, the Art Deco Central Library was ravaged by fire, damaging or destroying more than 1 million volumes and leading to years of rebuilding and expansion, including the Mayor Tom Bradley wing that descends four flights and is canopied by a skylight and whimsical chandeliers. Szabo gazed over the space, as if staring across a great land of genealogy, history, music, literature, philosophy, art, science and a computer lab, where days earlier a guard yelled “wake ‘em up, wake ‘em up” and a man in tattered clothes typed a screenplay while another read about jacuzzis.

It was reminiscent of a line from “The Great Gatsby” about a new world explorer coming face to face “with something commensurate to his capacity for wonder.”

A cop ascended an escalator. Szabo glanced at a new Anne Frank exhibit and then looked to his left.

“Hi, are you all visiting?” Szabo asked three people standing at the railing. “I’m the city librarian.”

“Oh, great,” said a man, smiling if a bit skeptical, as Szabo, with the infectiousness of a kid who just dropped a TikTok video, extolled on the library’s treasures in the faint drawl of his Alabama upbringing.

Szabo’s early years were itinerant. His father was in the Air Force and the family moved around — Florida, Germany, Ohio. They settled at a base in Montgomery, Ala., after his mother became ill with cancer and wanted to be near family. She died when he was 10. Szabo grew close to his grandparents, who kept a set of encyclopedias at the end of the couch near the TV.

He loved bound books and his father, who endlessly read Bram Stoker’s “Dracula,” would drop his son off at the base library at night before he went out bowling. Szabo said he felt “that sense of happenstance, to pick up a book and discover something. The idea of being behind the library desk was like being an astronaut to me. I loved the mechanics of how it worked.“

A librarian named Alta Hunt in Montgomery hired him to shelve books when he was 16 for $3.15 an hour. He went on to work at libraries as an undergrad at the University of Alabama and at the University of Michigan, where he received his master’s degree and was known as “Conan the Librarian,” a nickname that still draws a smile. His first library job after college was in a small town in Illinois. He later ran libraries in Clearwater and Palm Harbor, Fla., and was director of the Atlanta-Fulton Public Library system before moving to Los Angeles.

“I like the people who worked in libraries,” said Szabo, who earns $301,214 a year and lives in Eagle Rock with his partner Nicholas Kuefler. “I don’t know if it was an early gay thing but I found these folks were accepting and open. They certainly were more diverse than folks in other parts of my life.”

Roaming with Szabo through the Central Library is like gliding through chapters in a book; each room — most open, a few hidden — has a story. The Rare Books section holds 1,700 books on bullfighting — believed to be the largest collection in the U.S. — which leads Szabo to mention that Chinatown had a bullring in the 1840s.

One of the biggest prizes in Rare Books is the “Well of the Scribes,” a sculpture depicting Pegasus and writers from different cultures, which disappeared from outside the library during construction in 1969. Part of the sculpture, Szabo said, ended up in the bedroom “of a grizzled old guy” named Floyd Lillard, an antiques dealer in Bisbee, Ariz. Lillard, who bought the sculpture for $500 from a woman years earlier, said he read about the piece and contacted the library in 2019. Szabo flew to Arizona. Lillard led him into his bedroom “and there it was. I nearly fell on the floor. The other parts are still missing.”

One of the library’s most important projects is its New Americans Initiative, which has helped nearly 80,000 immigrants prepare for becoming U.S. citizens. “The program is strategically valuable to the library,” Szabo said, noting that it draws in families who for generations may see the library as integral to their lives. Recently in the library’s auditorium, 63 people from more than 20 countries waved small American flags and were sworn in as citizens.

Szabo recalled the day in 2015 when Sergio Sanchez, who won citizenship with the help of the library, accompanied him to Washington to receive the library’s National Medal from the Institute of Museum and Library Services, which provides grants and research development for libraries and museums.

“We took a bus past the National Mall and the monuments to the White House,” he said. “I watched the faces of Sergio and his wife, Francisca. Here is someone not from the U.S. He had no money. He’s an immigrant, and there he is in the White House with Michelle Obama putting her arm around him. It was the most American experience I’ve ever had.”

Riding escalators through the atrium light, past footfalls, whispers and those weighted with all they own, Szabo is a man balancing worlds. Attendance is not rebounding quickly from the pandemic, but the library has the largest collection of e-books in the nation — rising from 7.8 million checkouts in fiscal year 2018/19 to 14.5 million today. The Octavia Lab, where one can explore virtual reality and design PCB circuit boards, coexists with scenes like that of a woman yelling uncontrollably in the history department.

“I was at the reference desk,” said Julie Huffman, a genealogy librarian who has worked at the library since 2001. “The woman was screaming like she was being attacked but no one was around her. She was flailing. They sometimes throw chairs and it gets unruly.”

Huffman contacted one of three licensed therapists contracted with the library. “The woman was schizophrenic. The therapist talked to her for 30 minutes and deescalated it. I witnessed a miracle. If uniformed officers come, people sometimes freak out more.” Huffman has grown accustomed to such outbursts, but some of her colleagues have left the library or been reassigned to non-public-facing jobs, such as cataloging.

“I feel really good we’re helping people who live on the streets,” she said. “They’re treated with respect here.” She added that her morale changes with the hours and the number of incidents she encounters. “By the end of the day,” she said, “I’m ready to go home.”

The library has to “find innovative and creative ways to do what is at our core. Reading and literacy and access to technology,” Szabo said. “Unfortunately, we live in a world where we have to respond to other things.”

He noted that the Library Experience Office, which is run by Karen Pickard-Four and oversees security issues and mental health matters, costs nearly $16 million a year, money that could be spent on books, collections, community programs and renovations at branches.

He looked from the atrium toward the entrance. So much to do. He wants more breakout space for people to explore and read. The Job Career Center is “two clunky rooms that aren’t very inspiring.” The LAPD desk at the entrance should be more discreet, and he’d like to show off the atrium and rotunda more, give the place soaring glimmers of light, an openness of architecture and imagination. The Teen’Scape section needs a redo: “It feels like I’m in a ‘Saved by the Bell’ set. It doesn’t speak to today’s 15-year-old.”

The library is in talks to acquire Angel City Press, an independent publisher founded in 1992. The move, said Szabo, is a “natural extension of our mission to amplify the voice of authors, celebrate their work and preserve their stories ... that explore all that is quintessentially Los Angeles.”

Szabo, who recently popped up in Watts to read during children’s story time, is a man of possibility.

He walked to his office. Just inside the door hangs a portrait called “The Public Librarian,” a solitary man wearing a brimmed hat, books stuffed in his pockets and in a sack. His face is not seen. He is looking forward, eyes on the horizon, carrying what needs to be carried to wherever he is going, a place, one imagines, that will be better off when he arrives.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.