Must Reads: Who started the 1986 fire at the Los Angeles Library? Susan Orlean investigates in her new book

Curiosity is Susan Orlean’s superpower.

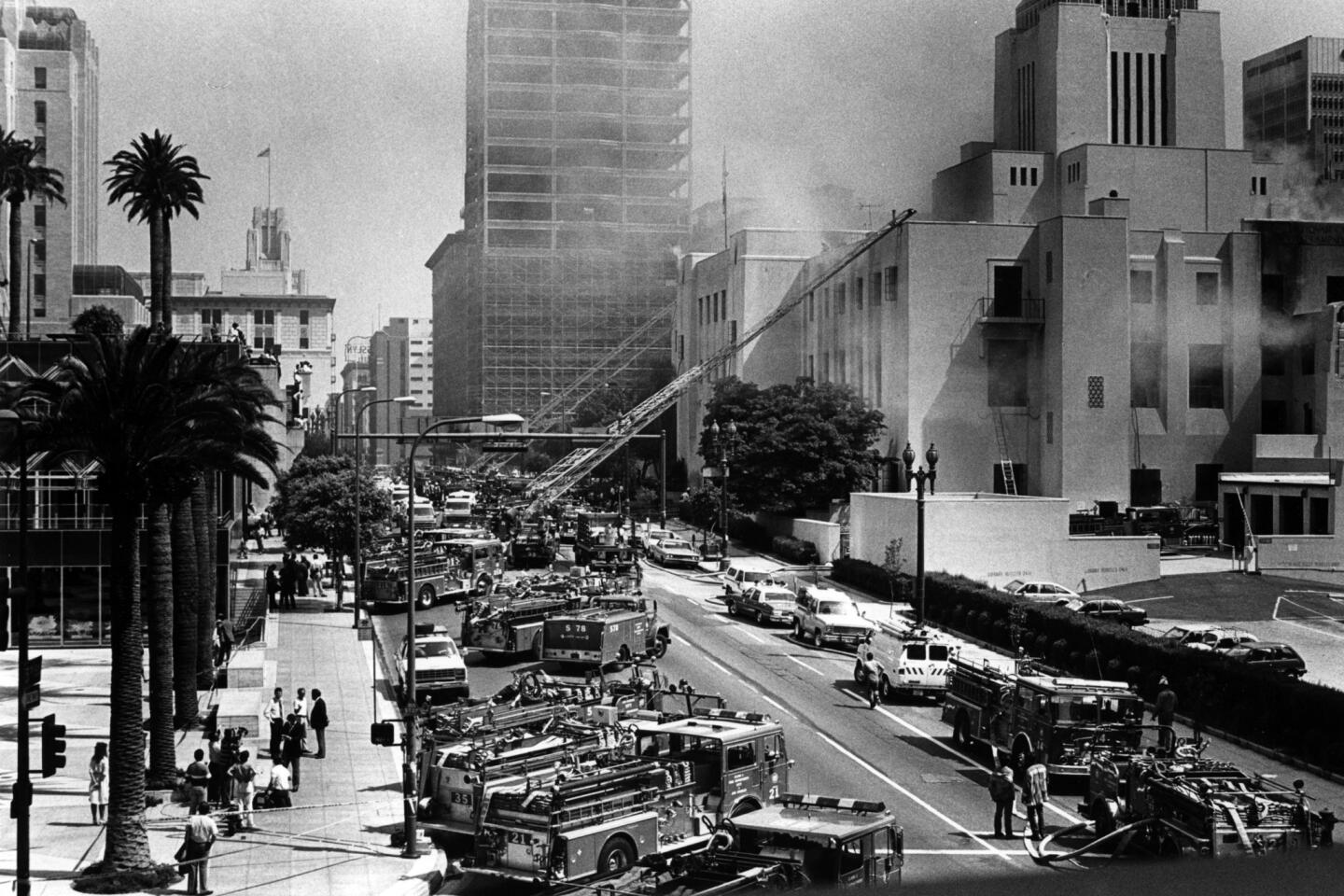

Hundreds of L.A. firefighters fought the devastating fire.at downtown’s Central Library on April 29, 1986. Thousands of people contributed to the Save the Books campaign afterward. Millions heard the news that the library was burning and then that it was caused by arson. But more than three decades later, only Orlean was asking who did it and why, and wondering whether anyone today should care. In a reverse “Fahrenheit 451,” Orlean took a fire and turned it into a book.

Titled — aptly and ingeniously — “The Library Book,” it tells the story of the mysterious fire that burned 400,000 books while also tracing Orlean’s love of libraries, from trips with her mother to taking her son. Along the way, she relates the unexpectedly colorful history and future of the L.A. Public Library.

“My first interest was writing a book about the day-to-day life of a big city library. I could have done that anywhere,” she said over lunch after we visited the library together. “I liked the idea of doing it in L.A., out of this contrarian idea that people don't associate libraries with L.A., which made it kind of delectable.”

That said, the 1986 fire (forgive me) was the spark.

A longtime staff writer for the New Yorker, Orlean had begun living in Los Angeles part of the year (she and her husband also maintain a home in New York). While exploring the city’s institutions, she visited the flagship of the L.A. Public Library and learned of its catastrophic fire. Although no people were seriously injured, the fire destroyed 400,000 books and damaged 700,000 more, causing $22 million in damages — more than $50 million today. It remains the largest library fire ever in America.

“This is an amazing story,” she said. As we walked through the library, Orlean — petite, stylish and with electric auburn hair — was greeted by staffers she’d gotten to know during her research.

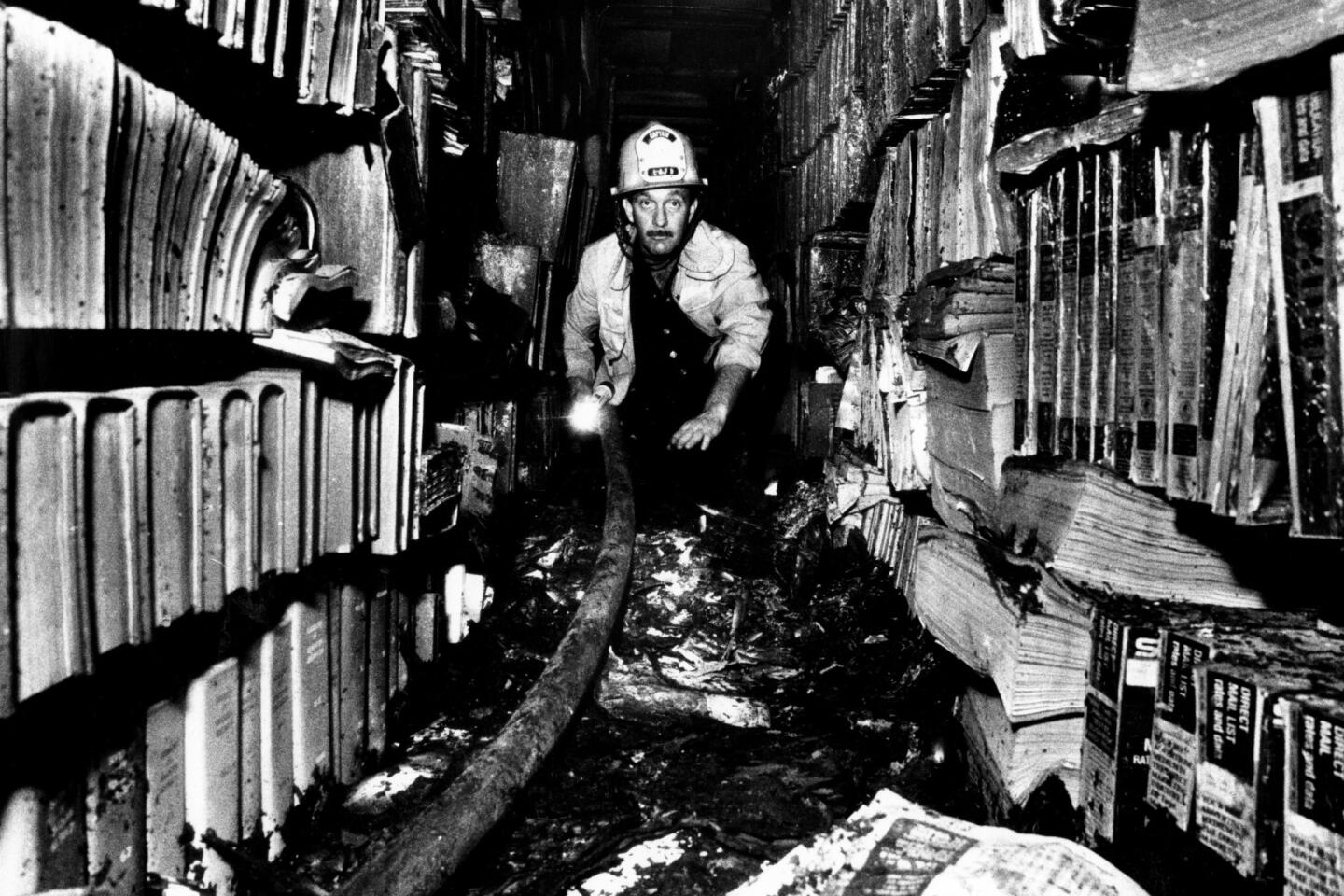

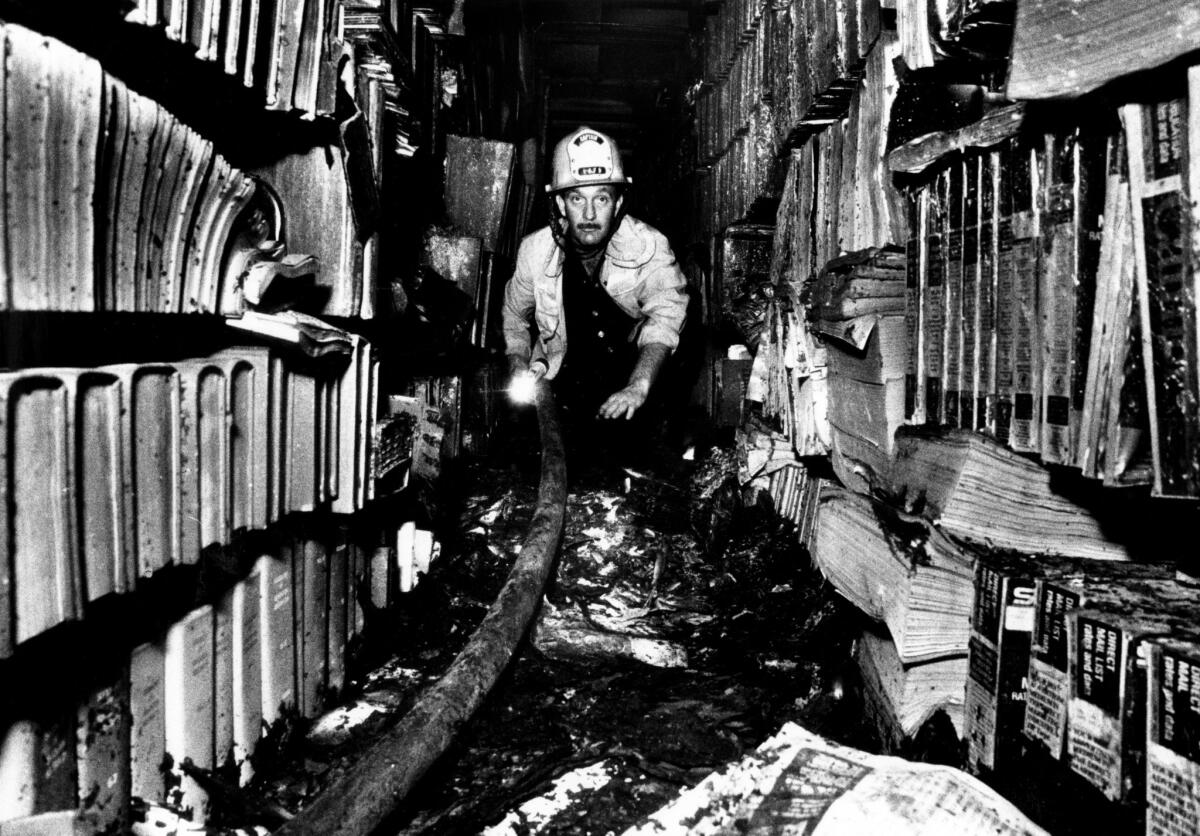

Tapping a concrete wall, she explained where the fire had started, in the stacks. Built as two secure concrete chutes within the original 1926 building, the stacks held hundreds of thousands of books and were connected by a catwalk for librarians. After the fire started — leaping across the catwalk from the first stack to the second — the chutes served as dual furnaces, books trapped inside with the fire.

“Their covers burst like popcorn. Pages flared and blackened and then sprang away from their bindings, a ream of sooty scraps soaring on the updraft. The fire flashed through fiction, consuming it as it traveled,” Orlean writes in her book. “It reached for the cookbooks. The cookbooks burned up. The fire scrambled to the sixth tier and then to the seventh. Every book in its path bloomed with flame.”

If you, like me, care about books, reading her brilliant, awful description of the conflagration feels like watching a snuff film.

Orlean agrees. “There's something that we feel deeply about books that we don't feel about other objects — you know, it’s an object!” It was as if she were trying to convince herself. “And nowadays, it's an object that can be replaced pretty easily. Even so. There is something about it that feels raw and vicious and aggressive.”

She is a lifelong journalist, known for her careful, in-person research, showcased in her New Yorker pieces and books, including “Rin Tin Tin,” a history of the Hollywood dog; “The Bullfighter Checks Her Makeup”; and (despite Charlie Kaufman’s fabrications in “Adaptation”) “The Orchid Thief.” So I was surprised to hear what she said next. It was so mystical.

“I think we have some association with books that feels like there was a soul in there,” Orlean said. “That there's a being in there, whether it's because writers have poured themselves onto the pages, whatever it is, I think there's something ineffable, mysterious about what makes books special, and I'm glad of that.”

This is one of the underlying ideas of “The Library Book” — that books, as both objects and ideas, are essential to the human project; that libraries are a vital destination that holds them safe.

So who would want to torch one?

That was a question L.A. authorities thought they had answered on Feb. 27, 1987, when they arrested 28-year-old Harry Peak on suspicion of arson. Peak was released three days later after the district attorney declined to file charges against him.

It is a fine mystery: Fire officials said there was an arsonist; Peak claimed, then disavowed, responsibility for the fire; no one else has ever been arrested in connection with the blaze. Whether Peak was the actual culprit is one of the central questions of Orlean’s book.

Orlean describes Peak as “the consummate storyteller.” Handsome and underemployed, he was a little bit rootless and quite a big talker; some news reports called him a part-time actor. He matched a sketch of the suspect. According to some (but not all) accounts, he was downtown at the time.

“There were two big storytellers in the book,” Orlean tells me. “One was Harry Peak and the other was Charles Lummis, who was an incredibly admirable and important figure in the history of LA.”

It’s an unexpected pairing. Lummis was the first city editor of the L.A. Times and founded the Southwest Museum; more pertinent to this story, he was also L.A.’s city librarian, a tenure Orlean details in the book. His hand-built stone home, which is now a museum on the southern edge of Highland Park, was known for the rowdy parties — he called them “noises” — he threw there. By any measure, Lummis was a significant figure in the history of Los Angeles, while Peak, apart from being the arson suspect, passed through barely leaving a mark. But, Orlean says, Lummis “was a bit of a fabulist, and he would tell stories that his friends didn't always believe.” So did Peak.

“We tell stories to ourselves, to each other,” Orlean says, as though forgiving the fabricators. “It's the lifeblood of being human.”

Perhaps she is sympathetic to the tale-spinners, because to be a writer in 2018 means to side with art. Right now, looking at this, you could Google “Harry Peak” or “library fire” and easily read the nuggets the internet spits out at you. Orlean’s project is bigger. It has to be.

“I think that one of the great burdens of being a nonfiction writer is this feeling that anybody could go look this stuff up,” she said. “I'm not delivering any information that no one else can access. I've gone on a trip to the pyramids and you're sitting around the dinner table and people say, ‘How was your trip? What were the pyramids like?’ Well, they could go look it up online, but that's not the point.”

Pyramids in Egypt or a 32-year-old news story in Los Angeles, the point is elevating the narrative so it tells us something about ourselves or the world, making it something worth noticing. “The history of the library is fascinating, and reminding people that libraries are kind of cool and interesting is exciting,” Orlean said. “I got very charged up about it.”

She admits that editors are rarely convinced by her story ideas on the surface. “There is some kind of pleasure that I find in saying, ‘I know you think that this couldn't possibly be interesting, but it really is. Give me a minute, I'll persuade you.’ That awareness that I'm having to prove to people every sentence of the way that this is something worth their time.”

“Seriously, this is super interesting. No, no, wait, wait, no. There's more,” she demonstrated. “And then there's more, and you're not going to believe. That's how it feels to me, that I'm tugging on somebody’s sleeve saying, ‘Wait, wait, one more second. Let me just tell you one more thing, you're not going to believe it.’”

From where we sat at lunch, we could see the library building. I asked our server if she knew that it was the site of the biggest library fire in American history. She didn’t.

“Ooh, I just got the chills,” the server said. She turned to Orlean. “And you wrote a book about it? What’s it called? What caused the fire?”

For generations of Angelenos, this will be the first they’ve heard of the fire, the massive fight to contain it, the thousands of books frozen in an effort to preserve them, the water damage, the stop-start effort to restore and expand the library where its visionary architect put it at the corner of 5th and Flower in downtown Los Angeles, of the man who may have set it aflame, maybe even of libraries around the world destroyed by fire through the ages, taking untold stories with them.

It’s all there. They just have to borrow “The Library Book.”

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.