How ‘Gender Queer: A Memoir’ became America’s most banned book

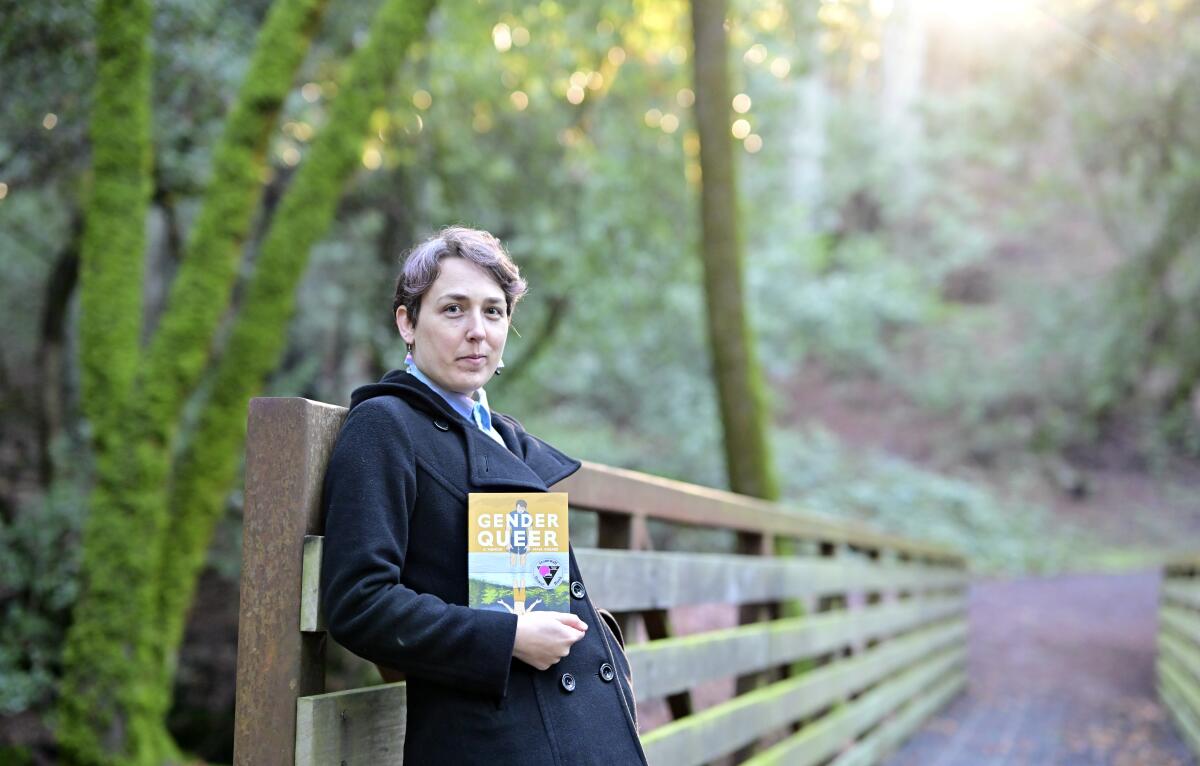

SANTA ROSA — Maia Kobabe grew up in an idyll. Cow fields threaded by a dirt road. No TV. Almost no internet. Nights fell over hills, stars shone bright, and Kobabe read fantasy novels, imagining other universes while searching for an identity, a glint of self to carry into the world.

“I lived in a shire,” said Kobabe, whose father and mother carved beads, weaved and sewed in a rustic community not far from this Northern California town. “I wish every kid had so much space to wander in. I wish every kid could walk out their door in any direction and be perfectly safe to catch snakes and frogs and pick berries.”

The pull of tides and the sway of nature were easier to decipher than the riddle within. Born with female anatomy, Kobabe didn’t feel like a girl, which became apparent in third grade when wading shirtless in a river during a class trip drew a reproval from the teacher. But boy wasn’t right, either. Kobabe was between two places and didn’t know where to stand. Was there anybody else in the world who felt like this? It was a mystery.

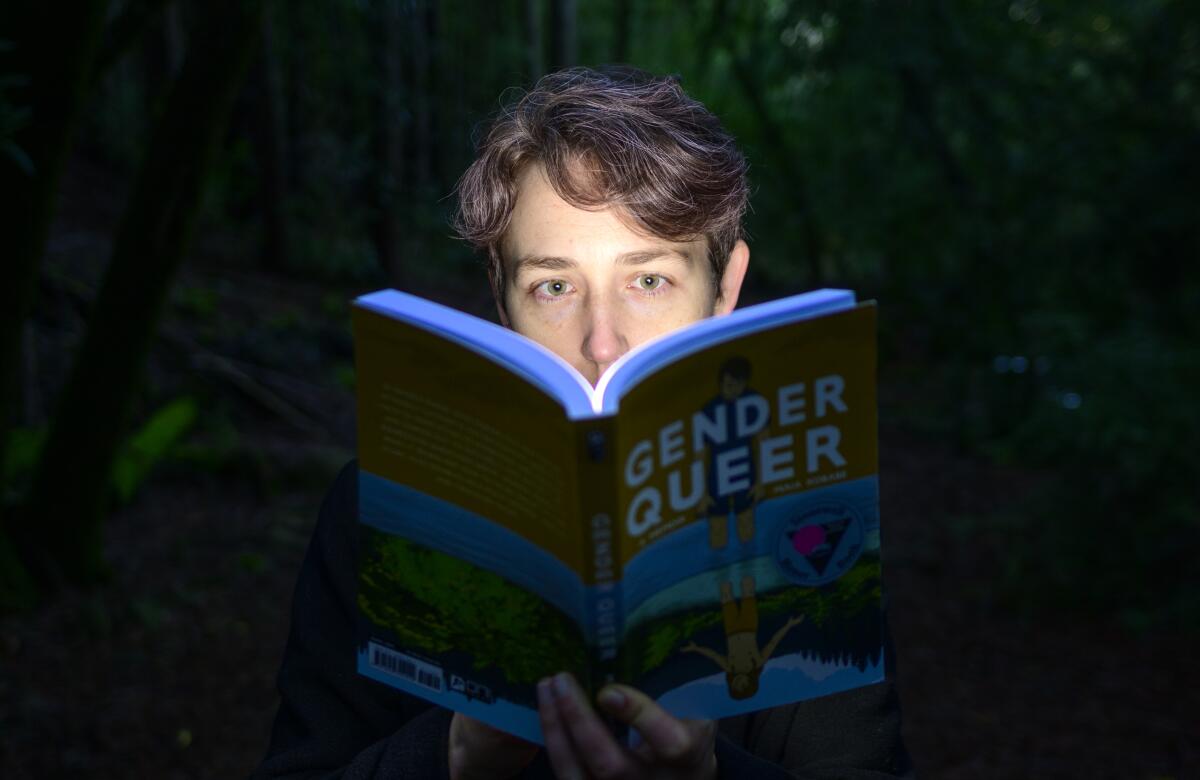

Kobabe’s insightful and moving coming of age discovery of identifying as nonbinary (using the pronouns e, em and eir) is told in the 2019 graphic memoir “Gender Queer.” Two years after its publication, the narrative, notable for its startling honesty and explicit drawings, became the most banned book in America, a target of school boards, conservative candidates, preachers and parental groups who condemned it as pornography aimed at impressionable children. Supported by librarians and vilified by Moms for Liberty, Kobabe was tugged from the writing life into the nation’s cultural wars.

“I feel a responsibility not to be quiet about censorship,” said Kobabe, who has written opinion pieces and spoken out against the banning of “Gender Queer” in at least 49 school districts in Florida, Texas, Michigan, Utah and other states. “We’re at this moment where I think there are more than ever trans and nonbinary actors, authors, artists, politicians, but there’s also more than ever legislation trying to limit the access to healthcare for trans students, access to sports teams or school clubs. Access to books. There’s this dichotomy of a renaissance of art and a backlash of legislation. I feel at the crossroads of hope and despair.”

The crusade against “Gender Queer” has largely driven its popularity and increased the size of Kobabe’s royalty checks. The memoir has sold more than 96,000 copies and has been translated into Spanish, French, Polish and other languages. It’s on the racks in airports. “There’s Danielle Steel and me,” said Kobabe, smiling at an array of ironies a kid who used an outhouse would never have anticipated. It has also landed Kobabe in the company of Toni Morrison, James Baldwin and Mark Twain, authors whose canonical works on race, gender and free expression have been on and off banned lists for decades.

“Gender Queer” became part of the pandemic landscape, when parents’ concerns — about school closings, vaccines and mask requirements — expanded to how race and gender were taught in classrooms. PEN America found that in an increasingly politicized atmosphere at least 50 parental groups, a number with ties to conservative causes, were working at national, state or local levels to ban books. Seventy-three percent of these groups and their chapters were formed since 2021.

“Gender Queer” quickly felt their wrath. But Kobabe — called a “sicko” when a northern Virginia school district became one of the first to forbid the memoir — was hearing from a more quiet yet no less resolute audience.

“I was surprised at how many people after reading the book came out to me, including people I have known for years, since high school,” said Kobabe, 33. “I had never suspected they were questioning their gender. But after reading my book they felt safe to say, ‘I actually relate to this. I’ve really been struggling with this as well, and I’ve never talked to many people about it.‘ I felt honored by those truths.

“It’s hard to articulate when you don’t have a language for it. It’s hard to imagine yourself into it if you’ve never seen it.”

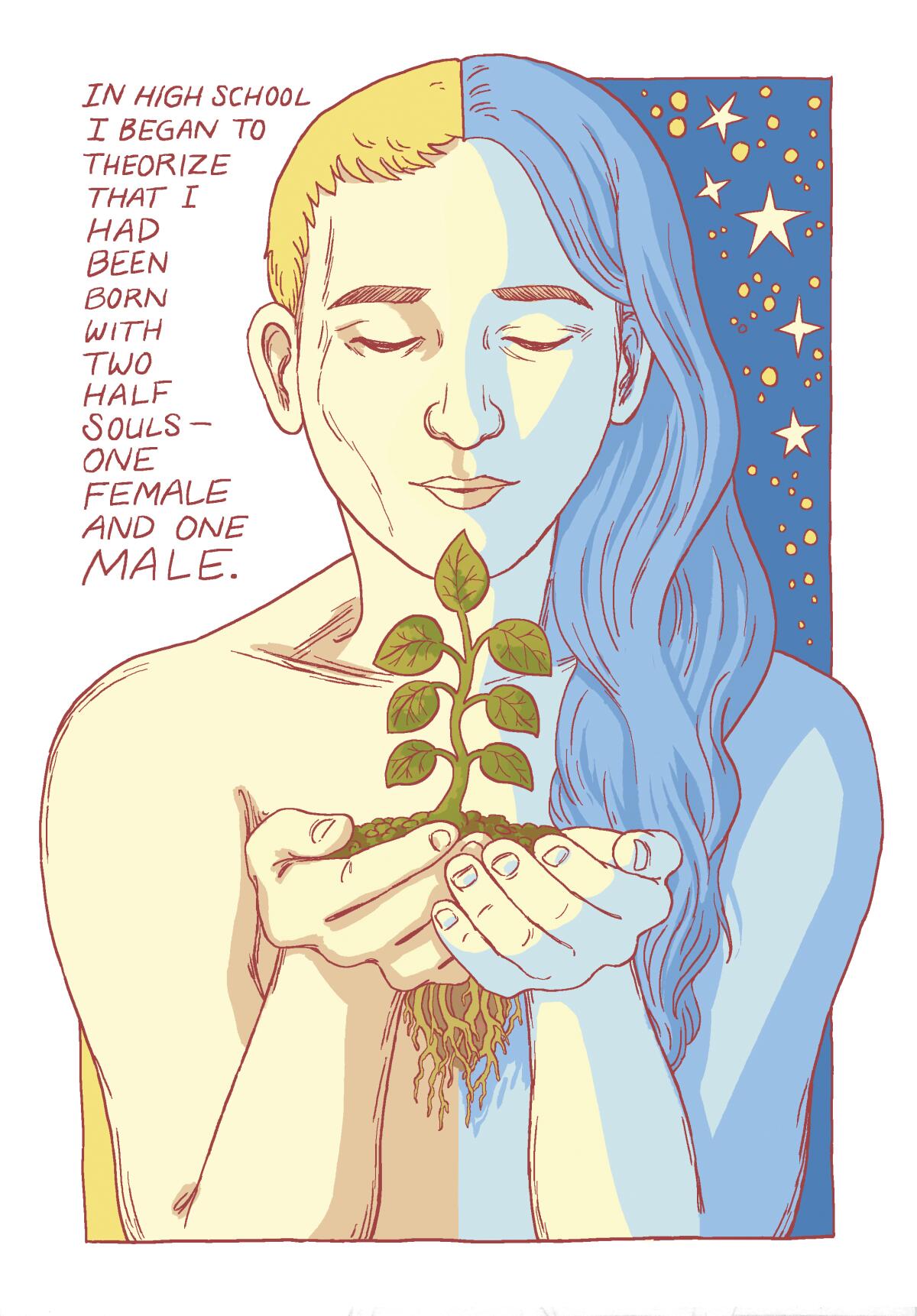

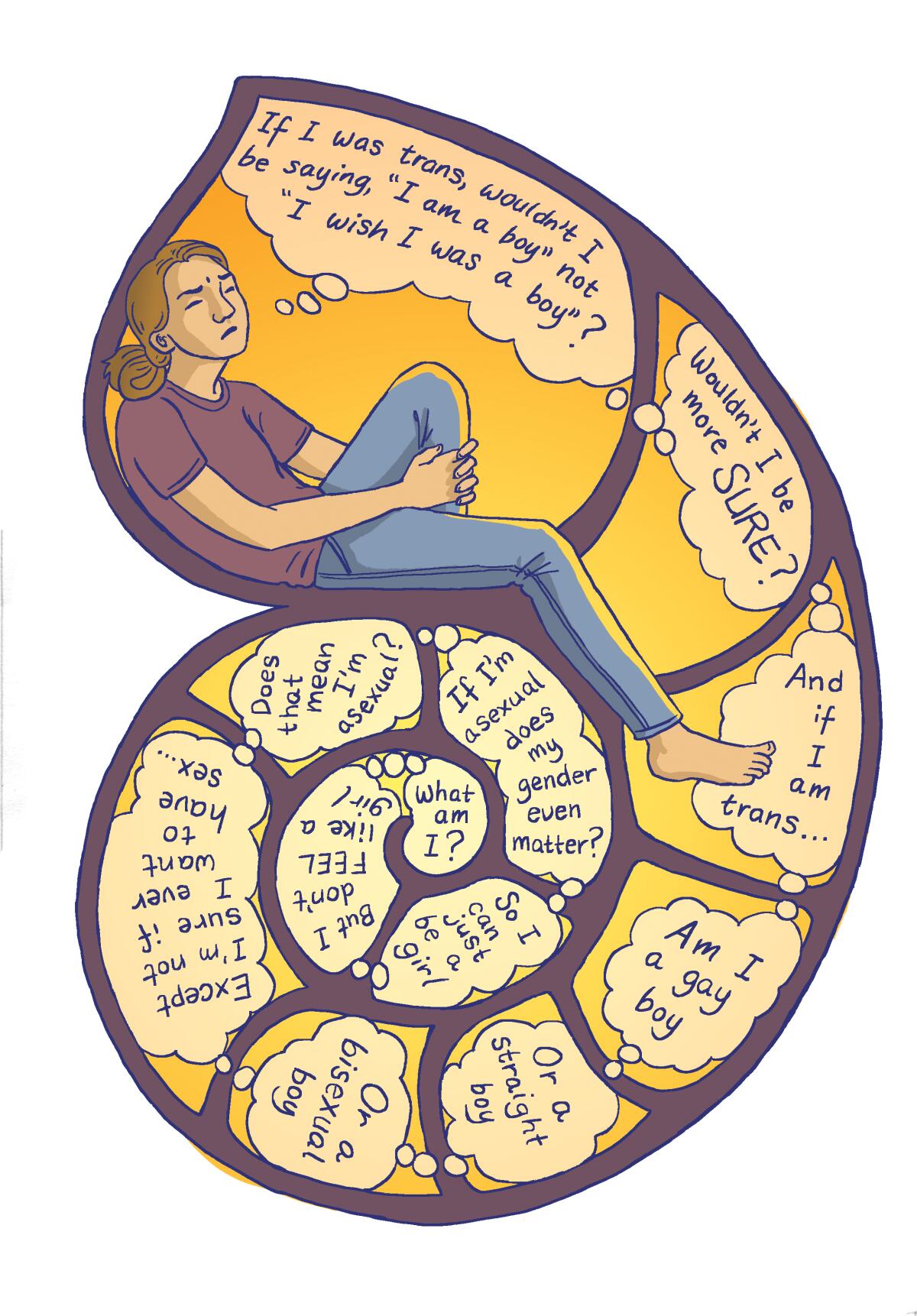

“Gender Queer” traces Kobabe’s bewildering search for identity; it was written to show eir family who e is. The book is a journey from child to young adult, marked by frustrations and epiphanies as Kobabe looks for binders to compress eir breasts, dreams of being a boy, experiments with sex toys, contemplates asexuality, studies genes and fetal development, blasts the music of David Bowie and tries to tell parents and friends about the reckoning inside, which Kobabe describes as being born with “two half souls — one female and one male.”

The book’s illustrations, including masturbation, an oral sex encounter and an erotic image of a man and boy illustrated on an ancient Greek urn, have been considered too graphic by many school boards and parents who are alarmed that children are increasingly questioning their gender and sexual orientation. In the states Kobabe’s book was challenged, it was mainly stocked in high school and public libraries.

“Gender Queer” is one of a number of graphic memoirs and fiction that parents and Christian conservatives have criticized as “grooming” children for LGBTQ “lifestyles.” Those accusations crystallized nationally in 2021 when Glenn Youngkin, running on a platform that included giving parents more say in how schools teach race and gender, was elected governor of Virginia.

That same year Republican Gov. Henry McMaster of South Carolina chastised a local school district for carrying “Gender Queer.” The governor said the memoir “contains sexually explicit and pornographic depictions, which easily meet or exceed the statutory definition of obscenity.”

Librarians across the country began pushing back. “People are saying they’re trying to protect children from pornography in school,” said Amanda Jones, a librarian in Louisiana who was threatened and harassed by conservative groups for arguing against the banning of books like “Gender Queer.” “But it’s false outrage. They’re targeting LGBTQ and other marginalized communities. My school is 96% white. How else are these students going to become empathetic humans? They have to know about other races and identities.”

Kobabe has grown accustomed to the clamor. Dressed in black jacket, floral hoodie, dark jeans, and maroon All Stars, Kobabe has the look of a skateboarder and the zeal of a naturalist who can riff on gopher snakes and the swiftness of spiders. An artistic stubbornness glides beneath a disarming earnestness. Kobabe is uncompromising in deciding how and what to draw, but in the same breath can lay in a phrase like: “It’s just a story about finding out who you are. Everyone has to find out who they are.”

On a recent dusk, Kobabe walked through downtown Santa Rosa, home of Peanuts creator the late Charles Schulz. Statues of Charlie Brown, Lucy and the ever-gleeful Snoopy stood amid redwoods in the half-light beyond the old Kress building. Kobabe passed a bench painted with the portraits of Salvador Dali and Alfred Hitchcock, which sits across from an alley mural of a tattooed woman with red lips, an octopus on her shoulder. Such aesthetic touches in a liberal enclave in one of America’s bluest states speak to Kobabe’s belief that unexpected beauty should play out amid life’s daily rhythms.

Kobabe graduated from Dominican University in San Rafael in 2011 and tried unsuccessfully for two years to sell a children’s picture book before enrolling for an MFA in comics at the California College of the Arts. Aside from teaching workshops, including at the Charles M. Schulz Museum, book sales and their income have allowed Kobabe to keep writing and drawing.

“I feel very financially comfortable right now,” said Kobabe. If a friend or a relative’s car dies, for example, “I can be the one to step up and provide a couple hundred dollars to fix it.”

Growing up as a teenager, Kobabe, who had dyslexia and didn’t fully learn to read until 11, scoured novels, comics and memoirs for inklings of queerness — voices that echoed within but had yet to find sanctuary.

“They were few on TV and barely in books,” said Kobabe, whose bedroom is crammed with 900 books. “When you did see them, it was an extremely tragic story where the character died or was kicked out of their home or was gay-bashed. It didn’t give you this optimistic sense of possibility for the future.”

Much of “Gender Queer” — mainly intended for teenagers and young adults, Kobabe said — is about the quest for that future while looking into a mirror that doesn’t always reflect what one hopes to see. Identity comes in fits and starts — in sudden revelations about finding the right clothes, the precise pronouns, and wondering when to come out in a label-obsessed world that can be dismissive and scornful. Identity in today’s America often means navigating the fault lines and crescendos between progressives and conservatives, becoming collateral damage in a larger drama.

Melanie Gillman, a graphic novelist and adjunct in the MFA comics department at California College of the Arts, said Kobabe has “a gentleness as a storyteller.” Gillman was troubled by the backlash against “Gender Queer” and blamed hard right politicians for taking several pictures in a 240-page book out of context “to stir up their bases. You never want a student or a colleague to go through any of that. It’s dehumanizing and stressful. Maia handled it the best anyone could. Every queer cartoonist has to deal with the issue of book banning.”

According to a survey by PEN America, 41% of the 1,648 titles banned in the 2021-22 school year deal explicitly with LGBTQ themes or have prominent characters who are LGBTQ.

In 2017, Kobabe taught comics to junior high students in local libraries but wondered if e should ask them to use the pronouns e, em, eir, which fit Kobabe’s sense of self more than they/them. Kobabe decided against it, writing in “Gender Queer”: “I wish I didn’t fear that my identity is too political for a classroom. ... I wonder if any of these kids are trans or nonbinary, but don’t have words for it yet? How many of them have never seen a nonbinary adult? Is my silence actually a disservice to all of them? ... Every time I fail to give my pronouns I feel like a coward.”

Matt Silady first came across Kobabe’s work in 2012 and said “Gender Queer” represented an introspective trend in the comic book world. “Beyond Superhero comics and beyond Manga, the real game changer has been the introduction of memoir as one of comics’ most important genres,” said Silady, chair of the undergraduate comics program at California College of the Arts. “Comics and memoir are such a perfect fit. Physically drawing your memories on a piece of paper. That’s compelling.”

He added: “Think of how vulnerable Maia had to be to tell the stories and truths in that book. That sometimes gets lost in the uproar.”

Kobabe walked past storefronts, into the art deco Barnes & Noble and headed for the queer books in the back. “This is my wheelhouse.” Kobabe, who talks of empires, imperialism, space travel and myths, reads across genres, mentioning “The Empress of Salt and Fortune,” a feminist fable by Nghi Vo about a nonbinary monk, in the same breath as JRR Tolkien and “Pride and Prejudice” by Jane Austen.

Kobabe gathered copies of “Gender Queer” from the shelf and took them to the front desk.

“I wrote this,” Kobabe said to the clerk. “I can sign them.”

As Kobabe scribbled, a teenage boy stood in the back lingering near but not reaching for the queer books. It was an image that would have fit into “Gender Queer,” a tantalizing yearning at the inexpressible, a discovery perhaps not yet made.

Kobabe left the books in a pile and walked out, crossing the street to the Treehorn Books, the scent of old bindings and ancient pages rising amid nooks and tall shelves and an illustration from a book by Beatrix Potter, who wrote “The Tale of Peter Rabbit.”

“I love Beatrix Potter,” said Kobabe, bending down to rearrange comic books. “I worked in libraries for 10 years. I have a desire to straighten.”

Kobabe’s next book is about teens, gender and sexuality. “The crucible of junior high.” It is expected to be followed by a prose novel turned into a comic about nonbinary youths and dragons. The realms of fantasy and the mystical are integral to Kobabe’s work — an image of Bowie as the Goblin King in “Labyrinth” is emblazoned on eir hoodie. But in the last couple of years, in a post George Floyd era marked by battles over equality and critical race theory, Kobabe has used eir notoriety to write opinion pieces and appear on radio and podcasts to highlight gender and diversity.

“I went from a midlist comic book author with one title out to being a person making national headlines,” Kobabe said. “A lot of companies want to get more gender inclusive. It turns out that DraftKings (a sports betting platform) has a queer employee group and they asked me to come speak.”

Being held up as a role model can be discomfiting. But Kobabe, who was young when first enthralled by Oscar Wilde and Andy Warhol, and whose queer sibling Phoebe is both hairdresser and confidant, sees it as a chance to give those tormented by their identity a sense of possibility.

“It’s really hard to imagine yourself as something you’ve never seen,” said Kobabe. “I know this firsthand because I didn’t meet someone who was out as trans or nonbinary until I was in grad school. It’s weird to grow up and be 25 before you meet someone who is like the same gender as you.” Pausing, Kobabe added, “I don’t know if you could imagine that you didn’t meet another man until you were 25. It would be hard to picture what your future would be like.

“I have so much privilege,” Kobabe said. “I knew that coming out I wouldn’t be threatened with my housing, job, healthcare. I’m white. I’m middle class. I’m able-bodied. I have loving parents who let me live at home rent-free. If I can use my position as having all this to smooth the road for others, that seems like a worthwhile thing to do.”

Many queer and nonbinary teens Kobabe meets today “are 10 years ahead of where I was. That means that by the time they’re in their 20s they can be working on a completely different problem, like, maybe climate change. They will move beyond the big [personal] emotional questions and struggles.”

Kobabe wants to be part of it. But a writer must write. Words fitted onto a page, pictures drawn. The quiet, daily work. “I feel pretty good these days. I don’t know everything about myself. I’m still learning through books I read and thinkers I encounter,” Kobabe said over a meal of Ramen noodles.

Streetlights came on and evening descended with a chill. Music played, a couple passed, the autumn leaves rustled, yellow and rust. Kobabe finished. The bill was paid. “If I’m not careful, I could become a person who does public appearances and has no time to write. I don’t want that.”

It was good to wander through town and talk, though, to be part of a simple pageant that sometimes passes so quickly it’s gone. But empty pages and stories awaited. Kobabe headed home, strolling past the mural painted years ago (“I did the dragonfly and, I believe, the newt”) of a scene very much like a shire, birds and flowers and hills rolling to the sea.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.