Column: I read ‘Gender Queer,’ the most banned book in America. And so should you

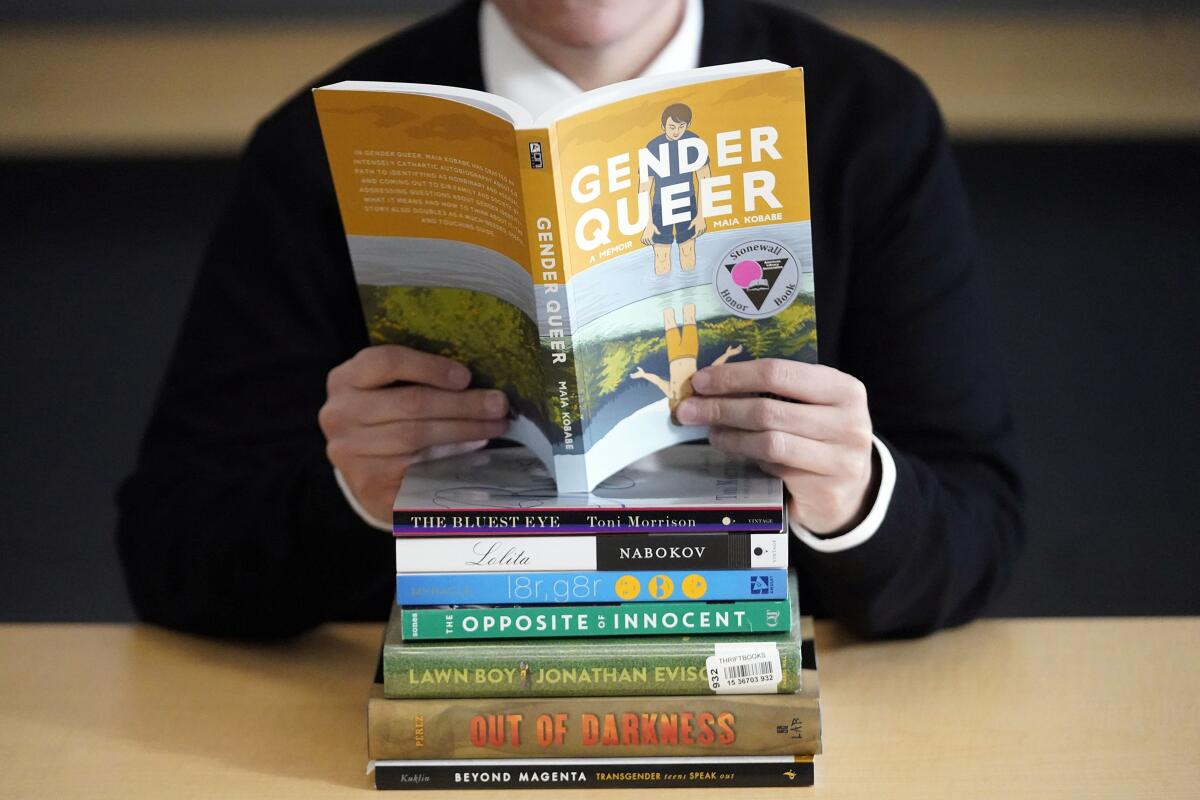

It doesn’t take long to read the most banned book in America, an award-winning memoir in graphic novel form called “Gender Queer” by Maia Kobabe. It’s about the illustrator’s yearslong quest to unravel what it means to be gender nonbinary — that is, to feel neither female nor male.

It takes even less time to understand why parents and PTAs around the country have pounced on the book, demanding it be disappeared from school libraries.

First published in 2019, “Gender Queer” covers topics guaranteed to be explosive in certain quarters: confusion about gender and sexual identity, unsettling sexual encounters, sexual fantasies, masturbation, menstrual blood. And of course, pronouns.

The criticism has been ferocious.

“This is pornography!” wrote one reviewer on Amazon. “The images and language in this book have no place on a bookshelf or anywhere near children, which is the target audience for this book. It shows oral sex, homosexual sex, etc. Please do not think this is teaching material. It is intended for grooming.”

The pernicious misuse of the word “grooming” aside, this memoir is explicit in places.

There are images of what some might consider kinky sexual behavior between Kobabe and a person she meets online. Of used menstrual pads. Of a bloody speculum after Kobabe’s first terrifying experience in the doctor’s office.

To be sure, this is not a book for little kids.

“I can absolutely understand the desire of a parent to protect their child from sensitive material,” Kobabe told the Texas Tribune late last year when the book began causing conniption fits in that state. “I’m sympathetic to people who have the best interest of young people at heart. I also want to have the best interest of young people at heart.”

Every once in a while, you stumble across a new word that perfectly describes where you are in life. For me, that’s kipple.

Any teenager or young adult in the throes of gender confusion or distress would surely find comfort and reassurance in Kobabe’s illustrated journey. In an interview posted last spring on YouTube, Kobabe told Anthony Allen Ramos of GLAAD that having a book like this “would have probably taken like 10 years of confusion and uncertainty out of my life.”

In the comments section under the interview, one person wrote, “I genuinely think that having this book as a middle schooler would have saved me years of feeling alone and isolated. I had access to plenty of books with explicit/graphic material from the library, but no books that were honest, earnest & relatable like this.”

It’s not just confused young people who might benefit from reading “Gender Queer.” It really should be required reading for grown-ups in places such as Texas and Florida, where cynical activists are using LGBTQ kids as fodder for their reactionary political agendas. Anyone clinging to the absurdly outmoded view that there are only two genders and nothing in between would benefit immensely from this book.

Kobabe includes a fascinating section about the philosopher Patricia Churchland, a professor emerita at UC San Diego, who popularized the concept of “neurophilosophy,” a discipline that connects neuroscience and philosophy. Electrical and chemical activity in our brain, Churchland posits, informs what we think and feel.

In her 2013 book, “Touching a Nerve: Our Brains, Ourselves,” Churchland delves into the biochemistry of fetal sexual development to explain why it’s possible to have female reproductive organs but feel like a male, and vice versa. It has everything to do with biology, hormones and the developing fetal brain. “In most cases,” writes Churchland, gender identity “is purely biological.”

“So, Lady Gaga was right,” writes Kobabe exultantly. “I was born this way.”

Like so many people who are betwixt and between, Kobabe struggles with the perplexing matter of pronouns.

“I already have short hair,” Kobabe writes, “and I’ve been wearing non-gender-specific clothes for years. I don’t want to change my name, but I like the idea of changing pronouns.”

California becomes to first state to require large retailers to establish ‘gender neutral’ sections for kids. It’s a good, symbolic move.

I don’t know about you, but it took me a while to become comfortable with the idea that people have the right to choose their own pronouns, and that, for some, the choice is hugely consequential.

In the end, Kobabe settles on the somewhat obscure “Spivak pronouns,” based on the gender-neutral terms used by the late American mathematician Michael Spivak. “E” takes the place of “he,” “she” or “they.” “Em” is used instead of “him,” “her” or “them.” And “eir” replaces “his,” “hers” or “theirs.”

Sounds a bit like Cockney slang, but if it works, why not?

In a moment of entirely relatable self-absorption, Kobabe’s otherwise supportive mother complains, “Why are you doing this to us?”

So far, according to PEN America, “Gender Queer” has been banned by 138 school districts in 32 states.

All the controversy, it seems, has been great for sales.

Maia Kobabe is famous.

Good for em.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.