Op-Ed: Gatsby, literature’s party animal, turns 90

I was in high school when I first fell for Gatsby, who turns 90 today — an “old sport” by any measure. He was 50 even then, but he appeared to me as Robert Redford in a pink Ralph Lauren suit and those “shirts of sheer linen and thick silk and fine flannel” that set Daisy sobbing in Chapter 5. How could a freckle-faced, Catholic-raised virgin resist that kind of bad boy: rich and handsome, with the best party house in town, even if he never did mingle?

Gatsby seems the kind of guy who would always have been popular. But the truth is more complicated.

------------

FOR THE RECORD:

Gatsby: An April 10 op-ed on the 90th anniversary of the publication of “The Great Gatsby” gave the title of a novel as “The Beautiful and the Damned.” The book is “The Beautiful and Damned.” —

------------

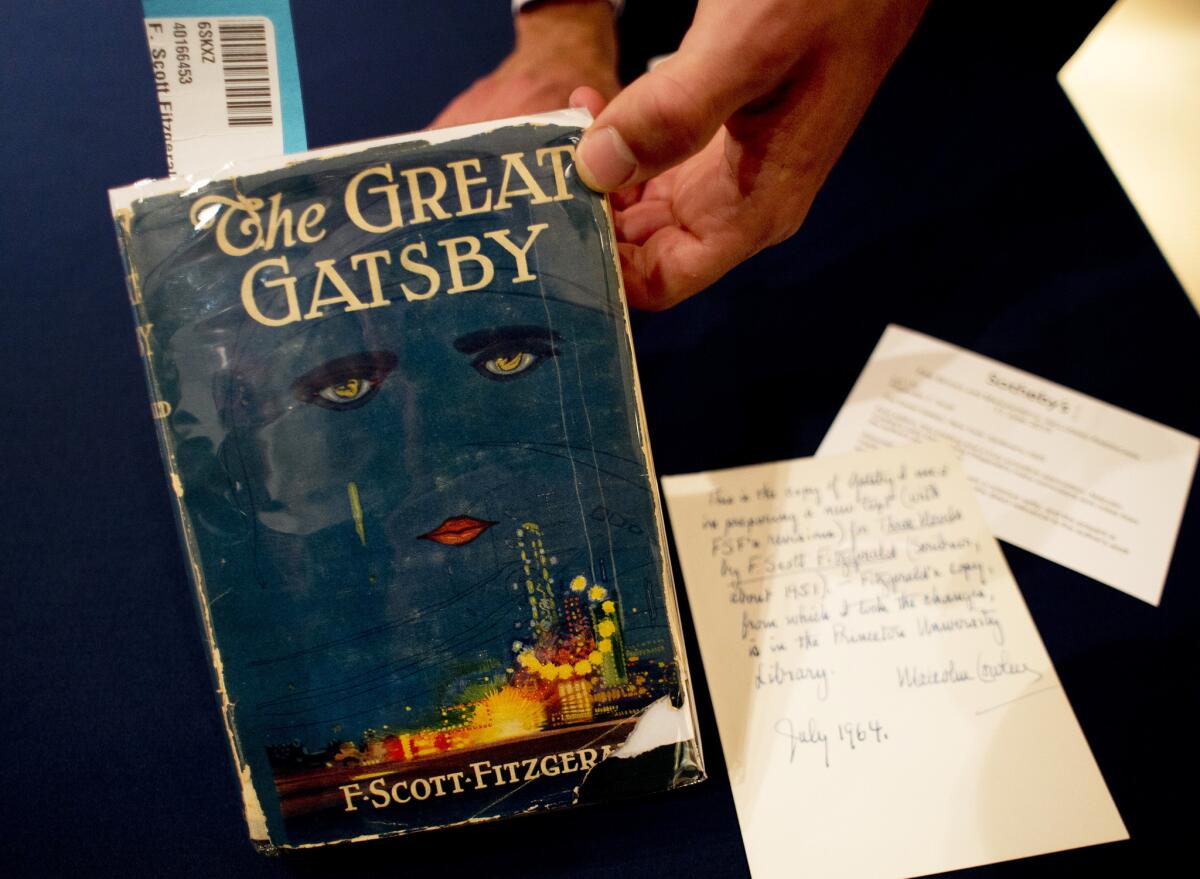

“The Great Gatsby” was published on April 10, 1925. Max Perkins, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s editor, thought it a masterpiece. The then-29-year-old Fitzgerald wrote of the novel before it was published, “It represents about a year’s work and I think it’s about ten years better than anything I’ve done.”

And it did receive some praise in its early days, for sure. The New York Times called it “a curious book, a mystical, glamorous story of today.” But others weren’t enamored. The New York World ran a review under the headline “F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Latest a Dud” (ouch!), and Perkins wrote at the time that so many people attacked him over the book that he felt “bruised.”

Sales were lackluster too. The first printing of Fitzgerald’s debut novel, “This Side of Paradise,” had sold out in days, and Charles Scribner’s Sons went back to press 11 more times in two years to sell almost 50,000 copies. Fitzgerald’s follow-up, “The Beautiful and the Damned,” also sold well enough to put 50,000 copies into print.

But the 20,000-copy first run of “The Great Gatsby” was followed by a mere 3,000 second print run, and no third. “Gatsby” was never out of print in the years before Fitzgerald died — at age 44, 15 years after its publication — only because Scribner’s still had unsold copies from those first two printings.

In fall 1940, Fitzgerald, writing to his wife, Zelda, of a new novel he was working on, lamented, “I don’t suppose anyone will be much interested in what I have to say this time and it may be the last novel I’ll ever write.” The last Scribner’s royalty check before he died that December was for $13.13.

Fitzgerald’s friend, the literary and social critic Edmund Wilson — who said of Fitzgerald’s death that he “felt robbed of some part of my own personality” — helped with the posthumous publication of Fitzgerald’s unfinished “The Last Tycoon.” He and Perkins, together with other Fitzgerald friends and fans, worked to keep critical attention on Fitzgerald’s work. Without them, “Gatsby” might have disappeared altogether from the American literary canon.

It was World War II, though, that gave “The Great Gatsby” a real boost in readership. As the war came to a close, 150,000 pocket-sized “Armed Service Edition” paperbacks were sent to soldiers, men who were perhaps left dreaming of swapping their uniforms for all those monogrammed shirts, and almost certainly of Daisy.

How the almost-forgotten novel ended up being chosen for this distribution isn’t clear. Maureen Corrigan, in her book about “Gatsby,” “So We Read On,” speculates that Nicholas Wreden, a member of the book industry’s Council on Books in Wartime who also happened to be the manager of Scribner’s bookstore, may have had a hand in it, a hand perhaps guided by Perkins.

The cover of the soldiers’ edition, in selling Gatsby as “the greatest of the ‘racketeers’ in American fiction,” may have led some to open it expecting Dashiell Hammett. That idea was perpetuated by the movie tie-in edition released by Bantam a few years later; on its cover, Howard Da Silva, as the character George Wilson, points a gun at a bare-chested and very buff Alan Ladd as Gatsby — a paperback that was reprinted five times by 1954.

The Bantam success influenced Scribner’s reissue of the novel, first in collected-work volumes, then in a 1957 student paperback. Sales of the latter — designed for baby boomers needing something beyond textbook excerpts to test their literary mettle — rose from 12,000 in its first year to 36,000 in 1958, 100,000 each year by 1960, and three times that before Robert Redford donned that pink Lauren suit.

Were students reading “Gatsby” because of its literary heft or because it was teachable? Likely both, but in any event the result was an explosion of scholarly analysis paralleling the growth in sales and the dawning recognition of an American classic.

This week, 90 years after its publication, “The Great Gatsby” is a phenomenon, having spent 476 weeks — more than nine years in total — on one national bestseller list, and “timed out” of most of the others. Internationally it has sold more than 25 million copies. It’s impossible to say how many scholarly articles it has given rise to, but a Google search of “Gatsby” returns 34 million hits.

So Perkins’ prescience has been confirmed. He wrote to Fitzgerald two weeks after the book’s publication: “One thing I think we can be sure of: that when the tumult and shouting of the rabble of reviewers and gossipers dies, ‘The Great Gatsby’ will stand out as a very extraordinary book.”

Happy 90th, Old Sport. And many more.

Meg Waite Clayton is the author of five novels, including the forthcoming “The Race for Paris” and “The Wednesday Sisters.” https://www.megwaiteclayton.com

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.