In 2008, artists Julio César Morales and Eamon Ore-Girón, working under the moniker Los Jaichackers (a play on “hijackers”), created a large cube that was part minimalist sculpture, part functional room. Built on a steel armature, its pristine exteriors were covered in mirrors and emblazoned with the Jaichackers name. Its interior space was used to screen videos of neighborhood bands doing covers of popular songs.

“Migrant Dubs” was intended to highlight the ways culture gets adapted — as when, say, a Latin party band turns Pink Floyd’s “Another Brick In the Wall” into groovy cumbia. It was a prominent (and noisy) component of “Phantom Sightings: Art After the Chicano Movement,” which was on view at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 2008 before traveling to five other museums, including El Museo del Barrio in New York and and the Museo Tamayo de Arte Contemporáneo in Mexico City.

When the tour ended in 2010, the piece was returned to Ore-Girón’s studio in South Los Angeles. But, by 2012, the artist, who was bouncing between cities, was finding it hard to hold onto a work that, crates and all, likely weighed somewhere between one and two tons. “It’s huge,” he says. “Just to move it would have cost me like $400 and then I’d need another place to put it.” So, when he moved out of his studio, Ore-Girón told the owner of the building he could sell it for scrap.

The Los Angeles artist’s solo show at the MCA Denver features early surreal works, as well as recent abstractions that capture elements of music and light.

Which is how a sculpture commissioned by LACMA and displayed in museums around North America ended up on the “free stuff” section of Craigslist — and in the hands of a DJ, producer and sound engineer from Michoacán.

“I like to refer to the cube as evidencia mágica,” says Enrique Tena Padilla, a.k.a. DJ Escuby, in a short film produced by the reunited Jaichackers that recently screened at LaPau Gallery. “It’s evidence of magic. That’s what this place is.”

If anybody is liable to make you believe in magic, it’s the magnetic Tena, 30, who is happy to talk John Cage one minute and quinceañera playlists the next. He is tall — 6 feet 4 — with a mane that channels ‘80s rocker (long and resplendent) and a style that is deeply saturated and gender bendy. On the morning of our interview, I find him decked out in a black suit, striped shirt and black-and-white saddle shoes trimmed with pink chiffon laces by Mexican designers Minena. Accompanying him is his sidekick Pierre, a scruffy terrier mix who in the Jaichackers’ video can be seen trotting about in a vest made from Mexican textiles.

Earlier this month, Tena took me on a tour of the cube, which has been reconstituted in the Pasadena backyard of Matt Jones, a co-founder of indie label Castle Face Records. There, it functions as a control booth for a recording studio in the nearby garage.

The last time I laid eyes on “Migrant Dubs” was in a New York museum more than a dozen years ago. The object before me is not the one I remember. Some of the mirrors are cracked (the result of all the moves) and Tena and a crew of friends have added a pitched wooden roof, which allowed them to insert windows and air conditioning. The interior has also been reworked. Out is the pink sound foam from the exhibition; in is an ornate arrangement of nearly 100 Beanie Babies.

“A cube is actually the worst form you can have for sound,” Tena tells me. The installation of the Beanie Babies — acquired en masse at an L.A. thrift shop — blocks external noise and gives the cube warmth. In each corner, sherbet-y cloth-covered panels serve as bass traps, which prevent lower registers from dissolving too quickly.

From boygenius’s joyful harmonies to Bad Bunny’s history lesson to Blackpink’s declaration of superstardom, it was a wild and rewarding Coachella.

Lining the walls above the control deck is an improvised shrine bearing postcards, a vinyl album by Beach House (one of Tena’s favorite bands) and the stuffed animals he had as a child. “My most sentimental objects,” he says, “they live in the cube.”

The cube is very different than it once was, but it retains its buenas vibras — good vibes.

Morales was floored when he first laid eyes on Tena’s reinvention of the space he’d conceived with Ore-Girón.

“It was breathtaking,” says the artist, who now also serves as director of the Museum of Contemporary Art Tucson. “To see it outside and not in the context of a pristine museum, but seeing it age. It’s like a beautiful old guitar. Like, there’s a new version you could get. But this one, as it ages, it still plays really amazing. Yet, you see the scuff marks and the broken areas.

“It’s like seeing an old friend we have not seen in 15 years.”

Since this is a story infused with magic, you might say that Tena didn’t find the cube, but that the cube instead found him.

Born and raised in Michoacán state’s capital, Morelia, he has been in music’s thrall from a young age. His parents enrolled him in the local conservatory, but Tena was frustrated by the academics. “I just wanted to play rock and roll,” he recalls. A teacher with avant-garde proclivities, however, introduced him to Cage, the 20th century composer known for his experiments with chance and silence.

“That changed my view,” says Tena. Music, he realized, didn’t have to follow a strict set of rules. “Mexicans aren’t great following rules anyway.”

He kicked off his career in high school, DJing at quinceañeras. When he turned 17, he moved to Mexico City to study sound engineering at a branch of the Tecnológico de Monterrey. A variety of music-related jobs followed, including a gig playing with Pussy Riot‘s touring band when they traveled through Latin America.

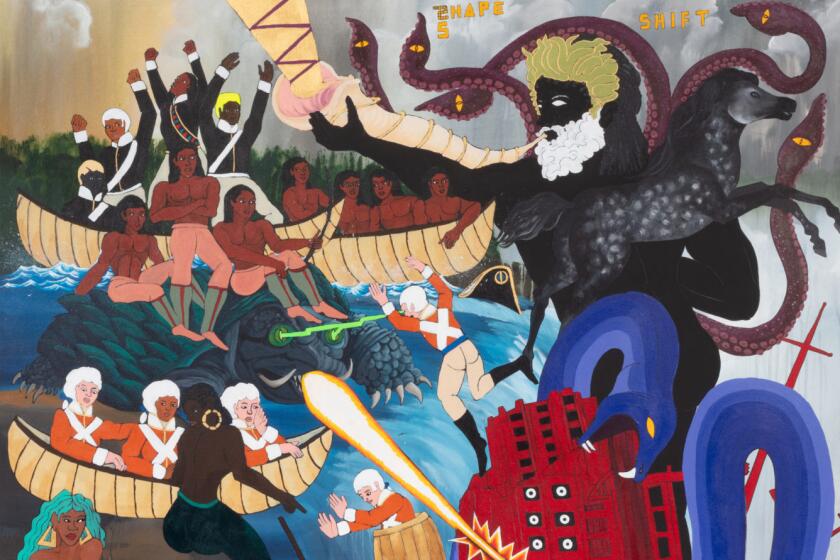

Triptychs, BMWs, colonial art and comic books all figured into recent solo shows by Umar Rashid and Frieda Toranza Jaeger at MoMA PS1

Work brought him to the U.S. on occasion — including production jobs at studios like the famed Sonic Ranch near El Paso, Texas. And over the years, he helped engineer albums for Beach House and others, including psychedelic garage punks the Oh Sees. He also recorded a one-off with his own band (Goodboy Inc.) and developed a side hustle as DJ Escuby — a name inspired by his fondness for “Scooby Doo.” He describes his playlists as “2007 quinceañera” — a nod to his days as a teenage DJ.

In 2017, after securing a difficult-to-get artist visa, Tena moved to Los Angeles in hopes of furthering his production career. When he landed, he staged a small ritual at the L.A. River, writing down three wishes on a piece of paper and inserting them into a bottle that he released into the water.

“What I’ve experienced in L.A.,” he says, “is that people will really help you.”

Around the time Tena was releasing his desires into the river, Christopher Mancinelli Rodriguez, an artist and musician based in Highland Park, was searching Craigslist for a free couch. He found the cube instead.

Intrigued by the idea that a major work of sculpture was being given away, he convinced a friend to help him retrieve it from Ore-Girón’s old warehouse studio. “We got there at the same time as a couple of guys who were going to scrap it,” says Mancinelli. “The owner gave us a trivia question and it was James Bond-related. Whoever answered it would get the cube.”

Neither he nor the scrap haulers were able to answer the question. (It was about a Bond femme fatale.) But the owner sensed that Mancinelli and his friend were serious about the cube, so he let them have it. Getting it back to Highland Park was no easy task. The crates were so heavy that Mancinelli worried they might crack an axle. “It’s the lowest I’ve ever seen a U-Haul truck go.”

The pointed work of marcelaygina gets museum treatment in Monterrey. Plus: Mahler’s Ninth and pre-gentrification Santa Monica, in our weekly arts newsletter

But without a place to install or store the cube, the crates sat on his driveway for months. So Mancinelli began to look for someone who might be willing to take it on. In the fall of 2017, he met Tena backstage at a Beach House concert at the Hollywood Bowl. Intrigued by the story of the art cube, Tena went to go check it out.

“The door was the only thing I could see,” he remembers. “And I was sold.”

In its new life, the cube finally fulfills an unrealized part of Los Jaichackers’ intent — much more so than if LACMA had acquired it. (In that case, it would have ended up in storage, only to be seen once every few decades.)

“Migrant Dubs” was inspired by music. Its form was influenced by record store listening booths, as well as a work Morales created for Peres Projects in 2003 — a wooden cube that served as a listening station for a sound piece inspired by the Cuban bandleader Damaso Pérez Prado. (Ore-Girón, who DJs under the name Lengua, helped make the mix for that show.) The cube was also inspired by a 1977 Marvel comic, which Ore-Girón owned as a kid, about the band KISS and a mysterious mirrored cube.

Most significantly, “Migrant Dubs” was originally intended to function as a recording studio, “so that we could record the bands we saw in every city,” says Morales, “but there wasn’t budget to do that.”

“To see it have a second life and to have it be a permanent architectural element in the city, it’s incredible,” says Ore-Girón, who these days is focused primarily on painting. “I feel like it was just destiny.”

The story of Tena and the cube is explored in a charming 30-minute video, “Psychomagic,” that Los Jaichackers created for LaPau, an exhibition that also included hand-painted signs inspired by musical concepts. The show closed last month, but the video is now available for viewing on the gallery’s website (lapaugallery.com).

“Migrant Dubs” was originally designed to mark the migration of musical ideas. Now, says Tena, it is “really tied to my immigration story.”

Later this year, his artist visa will expire. So on May 12 he is throwing a musical fundraiser at Zebulon to help cover the fees for his application to get a new visa. (Tickets for the event — which will include a DJ Escuby set — are available on DICE and updates will be posted to his Instagram, @escuby.wav.)

What does it mean for the cube if he has to leave the U.S.? Tena isn’t sure, but he remains open to whatever the future holds.

“I’m very conscious that the cube has a life of its own,” he says, “and I’m just helping it for now.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.