What can be conveyed with a circle or a square or a slender band of color? Perhaps it’s an outline of architecture. Or a pattern that summons a musical beat. Or the sensation in the retina when a ray of sunlight slips between mountain peaks and illuminates a high-altitude landscape. Maybe it’s the histories, brutal and sublime, embedded in some of those forms.

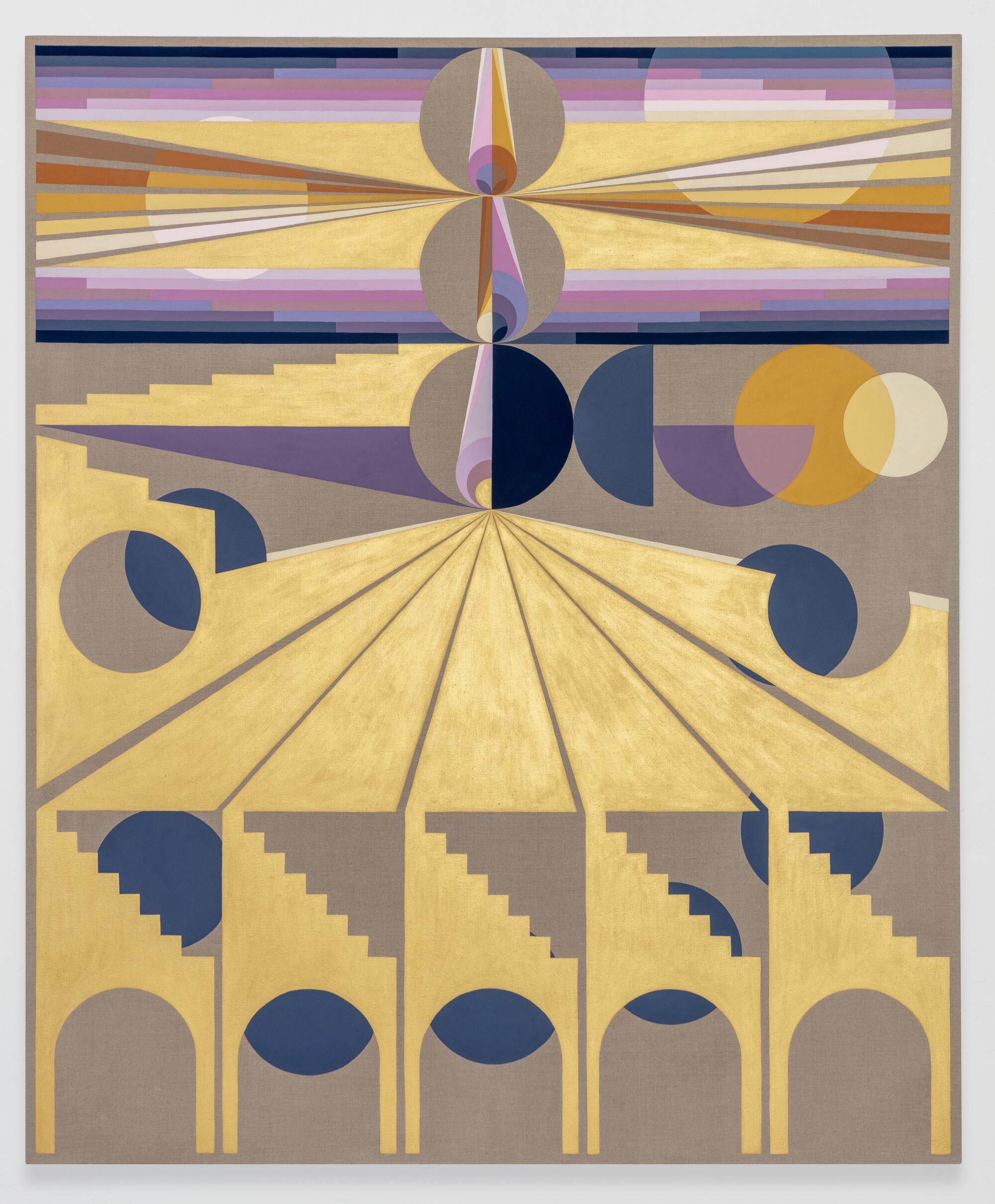

Look closely and this is some of what materializes in “Infinite Regress,” a series of paintings by Los Angeles artist Eamon Ore-Giron, on view through late May at the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver. In his solo show, “Competing with Lightning / Rivalizando con el relámpago,” linen canvases, earthy in appearance, serve as backdrops to cosmic arrangements of circles and rays of gradient color that recede into the horizon. All of it is framed by stepped architectonic structures that are rendered in luminous gold.

His elemental patterns can be found across cultures — in ancient temples or the early 20th century paintings of Russian suprematist Kazimir Malevich. But the ways in which Ore-Giron brings them together and remixes them is singular.

“When I started to think about what is my take on abstraction,” he says, observing a row of works-in-progress in his Eastside studio, “I always saw it through the lens of lineage.”

That lineage contains many threads.

Ore-Giron, 48, is the son of an Indigenous father from Peru and an Irish American mother from Arizona. He was born and raised in Tucson, but has spent periods in Mexico City, San Francisco and Guadalajara.

He spent a formative stint in Huancayo, a mining and agricultural hub in the central Peruvian highlands where his family is from — a region that is home to deep traditions in music and dance. There, in the late 1990s, he apprenticed with Peruvian painter Josué Sánchez, an artist whose work draws, in modern ways, from Andean art and craft.

“He taught me how to use highly-saturated colors in ways that could give them a bit more weight,” says Ore-Giron. “When you think of highly saturated colors, you think of Latin American work. In architecture, you think of [Luis] Barragán. Those are colors that in the palette of minimalism in the U.S. — no, you would never do that. But [Josué] gave me license to explore that in a sophisticated way.”

In Ore-Giron’s early figurative paintings, that brilliant color palette materialized in scenes tinged by the surreal.

At the MCA Denver are paintings such as “Cookin’ 1” and “Cookin’ 2,” both from 2002, which show his aunt and his cousin making humitas, Peruvian fresh-corn tamales. It’s an intimate scene, until you move in close and realize that the walls of the kitchen resemble the sky and the women’s bodies are penetrated by floating wisps of clouds.

What might a mountain spirit look like in the 21st century? Perhaps like two women cooking.

Other early works feature chonguinada dancers, in which performers of the central highland dance don rosy-cheeked masks and parody colonial Spaniards. Ore-Giron has set these against horizons of flat color, giving the performers an otherworldly feel. In addition, some canvases feature a recurring mestizo character from Andean folklore known as El Chuto.

“He is kind of magical and he’s a clown and he’s also kind of mischievous,” says Ore-Giron. “I’ve always identified with that character as an artist. Somewhat the clown in this dance that is kind of serious and has very serious undertones.”

Ore-Giron is an affable figure, an enthusiastic conversationalist who, in a single sitting, can veer from the multimedia canvases of Peruvian Modernist Jorge Eielson to the performances of German conceptualist Joseph Beuys to a wild anecdote about inhabiting a tiny room in Mexico City that once served as a dwelling for chickens. In between, he might jam in a comic analysis of how he views himself as the hybrid son of a Peruvian immigrant father and American mother — what he calls “this identity of being half.”

“I think my father is the coca leaf and I’m the cocaine,” he says. “He was this pure leaf that grew up out of the ground. I’m the processed, mind-altering product for the American market.”

The UCLA Hammer Museum’s much-anticipated biennial survey of new art produced in the city has just opened its fourth iteration.

After leaving Arizona, Ore-Giron completed his undergraduate degree at the San Francisco Art Institute in 1996, studying under figures such as underground filmmaker George Kuchar and multimedia artist Carlos Villa. In 2004, he landed at UCLA, where he completed his master’s degree in fine arts. Since then, Los Angeles has been home base — though he has lived abroad and in other parts of the U.S. for short spells.

This peripatetic life perhaps accounts for the polyglot nature of his artistic career.

In addition to painting, Ore-Giron has created videos inspired by Peruvian mining towns and created installations out of musical instruments. Over the years, his work has popped up at the Hammer Museum‘s “Made in L.A.” biennial and an exhibition about cultural power at SFMOMA.

He has also worked in concert with other artists — including notable collaborations with Tijuana-born artist Julio Cesar Morales. Calling themselves Los Jaichackers, the pair once crafted a room-size mirrored cube that functioned as sculptural listening station and remix studio. It was a highly visible (and audible) part of the 2008 group exhibition “Phantom Sightings: Art After the Chicano Movement” at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

A separate work by the duo, “Subterreanean Homesick Cumbia,” is on view at the Vincent Price Art Museum in East L.A., as part of the group show “Sonic Terrains in Latinx Art.”

The piece was inspired by a legend about the accordion’s arrival in South America. As the story goes, a German ship loaded with instruments sunk near the mouth of the Magdalena River, depositing accordions all over Colombia’s shores. In their video, Los Jaichackers return the instrument to its watery origins, showing an accordion bobbing alongside a riverboat to a bubbling soundtrack of cumbia.

Mexican American art has come a long way since the movement of the 1970s. LACMA’s ‘Phantom Sightings’ traces its zigzag path.

Music is not incidental to Ore-Giron’s work.

He has a deep knowledge of Latin American music — of the sort pumped at working-class dance parties — and he has a long-running side hustle as a DJ. Though to describe his DJ work as a “side” hustle is a misnomer, since DJing has been a through-line in his creative output since the beginning. (Ore-Giron has played guitar since he was a kid.) As DJ Lengua — “DJ Tongue,” in case you’re wondering — he has been part of a musical movement that has dipped into cumbia of the Mexican, Colombian and Peruvian variety and made it groovier: slowing it down and fusing it with the sounds of electronica.

With fellow DJ Sonido Franko (Joseph Franko, who is based in the Bay Area), Ore-Giron once established a small record label, Unicornio Records, whose big claim to fame is that it released Chicano Batman’s first album.

The fame, however, is only in hindsight, since that first album was a flop. “We had a thousand records,” recalls Ore-Giron, referring to real-deal vinyl, his preferred musical medium. “When a thousand records come to your house — it’s like twice the size of a barbecue. And they are really heavy.”

That experience didn’t stop him from pursuing other musical projects. Last month, Ore-Giron teamed up with Samy Ben Redjeb of the Analog Africa label to release a compilation of hallucinatory cumbias rebajadas, the reduced-tempo cumbias popularized by Mexican sonideros beginning in the 1960s. “Saturno 2000: La Rebajada de Los Sonideros,” as the album is titled, is a trippy tour of synth-soaked tunes from all over the continent made extra spacey by their languid pace.

The LA Boyz, featured as part of a LACMA Chicano show, remake music and messages.

Yet as critical as music is to Ore-Giron’s life, it is painting to which he has devoted the most focus over the last half-dozen years. “I had to be honest with myself and be like, you’re a painter, you’ve always been a painter,” he says, “and you don’t have multiple lives to live.”

It is on his paintings that the Denver exhibition is focused.

This includes his early figurative works, as well as numerous canvases from his “Talking S—” series. Begun in 2017, the series engages the deities of pre-colonial myth — deities that have become a daily part of Latin American iconography: the Aztec gods Coatlicue and Quetzalcoatl, as well as Amaru, a serpent deity from the Andes. Deployed as national symbols by the Indigenism movements of the early 20th century, these gods now regularly materialize in murals, restaurant menus and earrings on Etsy.

Ore-Giron digests them through the language of art.

“It’s a subversion,” he says. “How do you simultaneously refine a Modernist aesthetic and blend it with some aspect of Indigenous design and forms that are inspiring and beautiful and tie it into the legacy Indigenismo?”

There’s a lot going on beneath his spare forms.

His “Infinite Regress” paintings, however, are Ore-Giron’s best-known works.

The paintings, begun in 2015, elegantly synthesize the myriad strains that have engaged his interests over time. The linen, in its raw, unprimed state, conveys brownness of earth and of skin, as well as the rough texture of textiles. Motifs echo Andean Indigenous architecture, with its endless ascending steps — a design that appears frequently in Inca textiles and functions as a symbol of transition, from one worldly state into the next.

His color palettes, which can range from brilliant orange and blue to crepuscular pinks and purples, seem to evoke land, sky and light in its myriad reflective and refractive states. And, of course, there is gold: the ore for which Peru is best known, the ore that was stripped from Inca temples then shipped off to Spain, the ore that in the pre-Hispanic era was associated with the divine power of the sun, the ore transformed into economic asset by colonialism.

“People love ‘Infinite Regress,’ they are gorgeous works,” says MCA curator Miranda Lash, who organized the artist’s solo show. “But the conceptual motivations behind the paintings should not be sanitized. These are not just renderings of celestial bodies. There are direct references to the motivations behind colonialism. There’s a deliberateness in the choice of materials and colors.”

In the great taxonomy of Los Angeles strip malls, the one that resides at the corner of Cesar Chavez Avenue and Spring Street in downtown sits somewhere on the continuum between utilitarian and grim.

If the pieces also feel as if they have a rhythm and cadence, it’s perhaps because they contain music in their fabrication.

The circular patterns in Ore-Giron’s paintings are achieved by tracing the acetate dubplates he employs as a DJ. As the artist tells Jace Clayton (known as DJ Rupture) in a conversation published in the show’s catalog: “I’m interested in the synesthetic quality to the paintings.”

Certainly, there is a dynamism to the works that can’t easily be conveyed in photographs.

In photographs, Ore-Giron’s paintings can look flat. But in the MCA Denver’s galleries, which are punctured by skylights, it’s another story. On the windy April morning I visited the museum, the light conditions seemed to be continuously shifting. When a cloud was overhead, the paintings grew quiet; when the sun returned, the colors and the shimmer of gold came chattering back to life. It was a remarkable effect.

Ore-Giron’s art can elude tidy categorization. How do you sum up a body of work that has engaged so many materials and so many ideas over time? How do you pin a label on an artist whose life has been defined by having each foot in many places at once?

“My work is about identity on some level,” says the artist. “It’s not the insecurity of identity, but a reflection of identity. The reflection of this kaleidoscopic effect of Latin America. When people talked about pan-Americanism, people think of this idea of unity, but it’s a cacophony. It is still a cacophony.”

That cacophony, in Ore-Giron’s hands, can be stirringly, cosmically beautiful.

Eamon Ore-Giron: Competing With Lightning / Rivalizando con el relámpago

Where: Museum of Contemporary Art Denver, 1485 Delgany St., Denver

When: Through May 22

Info: mcadenver.org

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.