NEW YORK — In 1816, Kentucky-born portraitist William Edward West created a print depicting the battlefield death of British Maj. Gen. Edward Michael Pakenham at the Battle of New Orleans. At the time, the wounds of the 1815 conflict, the last of the War of 1812, were still fresh, and West did his best to convey the drama. In the background, U.S. soldiers in blue fight off invading British redcoats. In the foreground, a British officer holds the dying Pakenham in his arms. Gen. John Lambert, who assumed command after Pakenham died, is shown burying his face in a white handkerchief as he weeps.

But “Battle of New Orleans and Death of Major General Packenham” — West misspelled the general’s surname — is more bizarre than it is cinematic. Horses and men are out of scale, and Pakenham’s body is awkwardly situated within the composition. Amid the war dead lies a horse on its back, presumably in a state of rigor mortis but better resembling a house pet in need of a belly rub. Ultimately, the most intriguing thing about the print is the way the artist revised it. Lambert, it appears, was not a fan of being shown in tears, because when West reissued the print in 1817, the handkerchief was gone. Instead, the general is shown drawing his index finger toward his brow, as if announcing a new pimple.

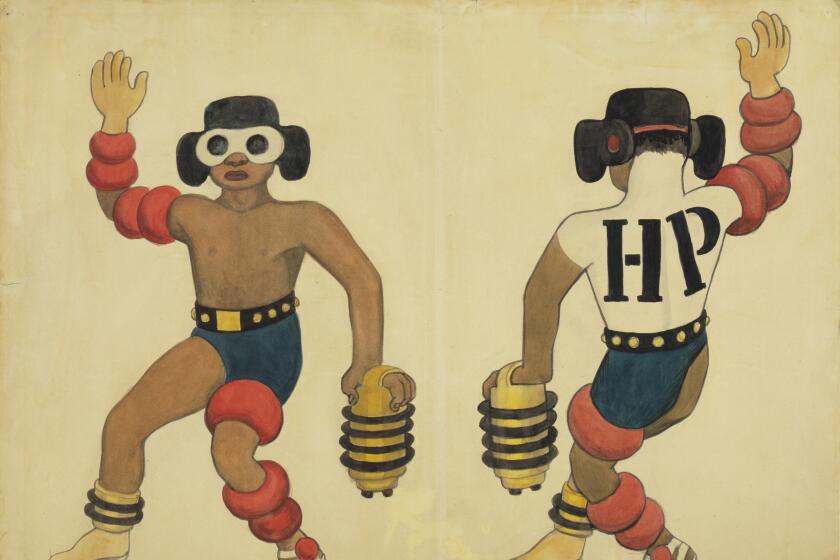

This absurd bit of revisionism was on my mind as I ambled through Umar Rashid’s solo exhibition “Ancien Regime Change 4, 5, and 6” at MoMA PS1 in Queens last month. The Los Angeles-based artist has long been preoccupied with the mythmaking embedded in historical painting. Such artists were generally not at the events portrayed in their works; in fact, in some cases they weren’t even on the same continent. Making things up was part of the deal. Rashid has taken that idea and run with it.

In drawings and paintings bearing some of the awkward poses and portentous titles of the genre, the artist has tracked the fictional battles of civilizations real and invented. In the Hammer Museum’s pandemic-delayed biennial, “Made in L.A. 2020: A Version,” he created a suite of paintings titled “The Battle for Malibu” that riffs on the history of Spanish missions in California — complete with a demon that shoots lasers out of its eyes.

What is Latin American identity built on? ‘Diego Rivera’s America’ at SFMOMA and ‘Reinventing the Américas’ at the Getty Center seek answers

The now-closed show at MoMA PS1 focused on the “history” of a land known as Novum Eboracum, a.k.a. New York. In a 6-foot-tall canvas from 2022 titled “Tales From Turtle Island #1. The secrets of the Onguiaahra (Niagara) Falls and the first death of Venus, in furs. Gamera be praised,” we see mermaids beckon as boatloads of Dutch and Indigenous men prepare to slip over the edge of the falls. Meanwhile, a Neptune-style god blows a conch as a snake faces off with Gamera, a turtle kaiju of Japanese film. In another painting, a pair of deities in a vintage convertible descend on a scene in which two soldiers, also lovers, are surrounded by enemy troops under a glowing sky.

If an overheated imagination worked for early printmakers, it works just as well for Rashid.

“Ancien Regime Change 4, 5, and 6” was one of two solo shows on view at MoMA PS1 until earlier this month that offered an enjoyable jolt to the nervous system — not to mention the history of art and design. “Autonomous Drive,” the first major solo show in a U.S. museum by Mexican artist Frieda Toranzo Jaeger, subverted the machismo of car culture and reimagined 16th century religious painting in queer and sensual ways.

She used a hinged triptych — a format commonly employed in the creation of Christian altars — to render the dash of a late-model luxury car in acid shades of green. Another triptych, a 2019 painting titled “Sappho,” shows two women in flagrante delicto in the backseat of a vehicle that explodes with riotous nature.

One of the exhibition’s showstoppers was a large-scale hinged canvas that stood on the floor — more than 7 feet high at its tallest — titled “Hope the Air Conditioning Is On While Facing Global Warming (part I),” from 2017. The painting consists of four panels that have been assembled to evoke a BMW i8 and its flamboyant wing doors. Through the windows of this painterly vehicle, we see idyllic blue skies and delicate flowers, as well as a landscape in flames.

The freedom a car purportedly gives us is also at the root of our imminent destruction.

Other car-themed paintings included a handsome triptych from 2022 that shows a scramble of tailpipes, navigational systems and bits of landscape rendered in the austere color palette of a freeway. But as in Toranzo Jaeger’s other work, there is a playful sensuality as well. To enter a car is to enter its body; to enter this triptych is to engage the elegant black vertical void at its center — along with a literal depiction, in one corner, of a trio engaged in ecstatic sex.

Matt Johnson’s monumental ‘Sleeping Figure’ sculpture justifies a trip to this year’s Desert X 2023 biennial.

The artist’s focus on transportation extends to the interstellar. The exploration of space has often been rooted in the language of colonialism — there is an entire Wikipedia page devoted to the “colonization of Mars,” for example. And its symbols are often aggressively male. (Cue Jeff Bezos in a penis rocket.)

Toranzo Jaeger appropriated the spaceship to new ends: In a three-dimensional painted work from 2022 titled “For new futures, we need new beginnings,” she assembles a spacecraft out of painted canvas that features a blooming potato plant and patterns that evoke the labia — some rendered in embroidery. On one side of her imaginary rocket, two women strike the insouciant pose of Lucas Cranach the Elder’s 1529 canvas, “Venus standing in a landscape.”

Symbols of the past are repurposed in the present in service of imagining a fantastical future.

This is a tendency Toranzo Jaeger and Rashid share in their work.

Rashid gleefully smashes together styles from various eras, his canvases drawing from colonial-era manuscripts, Persian miniatures, Japanese screen painting, comic books and ’80s wild style graffiti. In the final gallery of the show, he drew from the flamboyant aesthetics of Afrofuturism. There, a series of capes — of the sort Sun Ra might don at a performance — were displayed on a wall, each evoking the civilizations the artist depicts in his work. Also displayed was a sculpture of a Jumbotron that looked as if it had crashed into the room from outer space and commanded the viewer to “Sink” or “Synchronize.”

Rashid’s warped histories often extend, like Toranzo Jaeger’s, into otherworldly realms.

In an artist conversation organized by the Getty Research Institute in 2021, Rashid said, “The biggest tragedy that happened to the African American was that we were cut off from our culture, we were cut off from our language, we were cut off from our religion, we were even cut off from our names. And when you lose your name and you lose your culture, you lose your identity.

“It’s a gap that can’t be filled,” he added. “The best way that I can fill that loss is ... create a parallel universe.”

His universe un-erases the erased, but it isn’t reactionary, nor is it a site of gauzy triumph. It is complicated and messy. Everyone — white, Black and brown — is implicated in the struggles for power.

With the help of his mother, Ms. Freddie Mae Wiley, L.A.’s native son is on the search for a radical freedom divorced from fixed Western notions of race, gender and class.

The most compelling of these works are those inspired by European equestrian painting. Think of Jacques-Louis David’s majestic 1800 canvas of Napoleon gallivanting across the Alps in a billowing wrap worthy of an Oscars red carpet. It’s a form that has been tweaked before, perhaps most famously by painter Kehinde Wiley, who has regularly inserted the Black figure into these heroic poses.

Rashid borrows from the form and complicates it further — most intriguingly in a pair of larger-than-life canvases that figured early on in the MoMA PS1 show. One featured a mounted Black female figure in a robe brandishing a machete over two Black soldiers engulfed in a brutal sword fight. The sky is rendered in messy drips, and spray painted upside down above the scene in bright orange is the word “alive.”

It’s unclear who fights for whom, who has the moral high ground, who is the hero in this battle, who history will venerate. No matter which way you edit or revise it, war isn’t heroic. It’s an enterprise painted, ultimately, in blood.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.