This story is part of Image issue 12, “Commitment (The Woo Woo Issue),” where we explore why Los Angeles is the land of true believers. Read the whole issue here.)

On June 12, 1971, Sun Ra, jazz piano prodigy from Birmingham, Ala., by way of Saturn — a planet he insists he visited during an alien abduction when he was a child — put a curse on Los Angeles. He was performing with his band, the Sun Ra Arkestra, at J.P. Widney Jr. High School when someone had the misfortune of cutting the lights. The band had just finished a rendition of “Walking on the Moon,” a song that admonishes, “If you wake up now, it won’t be too soon,” implying that it’s both too late and inevitable — the grand stupor of the human experience has been punctured by the brutal clarity of the space age. It’s rumored that it was the school custodian who stole the light because he wanted to go home and considered proctoring the concert a chore and not a privilege.

The hour-and-25-minute recording of the event was generated by a tape recorder placed center stage, and in the years since, it’s warped its way into a portentous aura. Distortions, squeals, fuzz and machine hum lurk within the music so that when the conflict arises it seems to have been brewing throughout the show. When darkness descends on the auditorium, the instruments are still plugged in and the tape is still documenting. Some of Ra’s tirade is redacted by organ and amplifier reverb, and howling and stomping from the audience, which all begins to sound like an avant-garde high school cheerleader squad. Emergent from the cacophony is Ra’s peeved voice promising, “This planet needs me, I don’t need it, lights turned out on me ’cause lights turned out on the whole planet…”

Before coming to Los Angeles, Ra and his Arkestra had been touring in Europe through countries that revered their music. They were living in Oakland, in a house owned by the Black Panthers. Ra was about to teach a class at UC Berkeley called “The Black Man in the Cosmos” and film “Space Is the Place,” a cinematic autobiography, lush with myth and ghetto reality. His experience at this show in Los Angeles, the comedown from a time of acclaim and empowerment, left him lucid with the kind of heartbreak that begins as indignation.

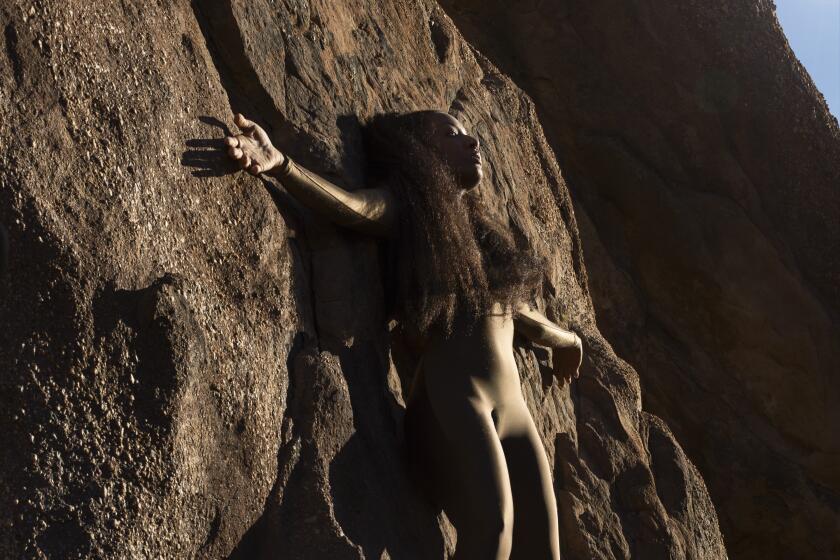

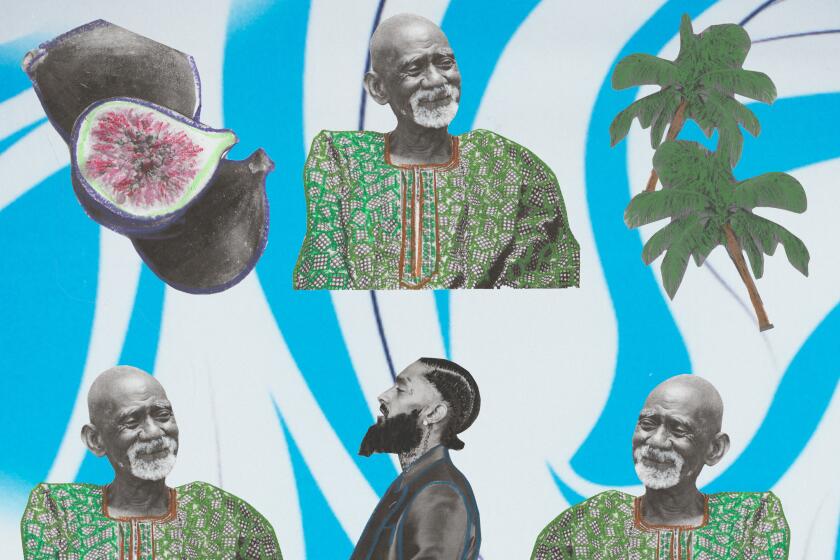

Experimental filmmaker and photographer Sophia Nahli Allison shows you what’s possible when you allow yourself to be led by spirit.

“I’m a sun god on a lonely planet,” Ra continued that night at Widney. “The light was crucified on this planet, there’s nothing but darkness anyway. And it’s knocking at your door.” It was embarrassing to people who love and worship the mighty Sun Ra. It was one of those misfortunes that no one even mourns right, a plight obscured by spectacle. The crowd’s hysterics grew so unbearable that Sun Ra left the stage. Pianist and composer Horace Tapscott was in the audience, close to tears. Marshall Allen, who was performing with the Arkestra that night, still gets a strange pulsing in his jaw, like the frequency of the last note played before the lights went out, when he visits Los Angeles. “You wake up, Black people don’t need to wake up, they have me, you don’t have anything,” Ra declared in a constricted tone. He knocked the city unconscious.

What would it require to lift the curse and extend Ra his deserved hospitality in Los Angeles, 51 years later? With this question in mind, I formed an impromptu Arkestra of lights with artists Nikita Gale and Arthur Jafa. We played the recording in an empty theater at the L.A. music and arts venue 2220 Arts + Archives, and Nikita pierced the cadence of Sun Ra’s rant with a roving spotlight while AJ filmed. Nikita then created three images by layering all the filmed footage in a time-lapse spanning the duration of the spoken recording, and collapsed it into static kinesis. Below is a frayed, blurry transcription of what transpired — a conversation between Sun Ra and the light, which reinstates and then displaces and maybe even lifts his curse on Los Angeles.

Seven amber eyes abandon their spotlight sockets and blink like a just-punished child who doesn’t want his father to see him flinch — Sun Ra’s ghost reappears in fragments and haunts us with delight that only resembles a curse to those who prefer suffering to catharsis, those who cannot become themselves. Freedom, Ra instructs us, is for those who possess self-discipline. Even as a ghost, Ra has an inherent disdain for arbitrariness and idleness. His acoustic gleam hinges on boundaries, Saturn’s rings hula-hooping Earth as Sun Ra’s tone-science, distributed as sidle, cackle, ballad and soul. Ra chases away the joyless with brightness that aches when it dims. He is a loving tyrant in some ways, a vulnerable subject in others. Ask him to play music in the dark and he will hand you a blindfold. Ask him to meet you on his comeback road and he will outlaw Los Angeles.

I had a theory that alien abduction stories like Ra’s were misreadings of childhood abuse, attempts at making it harrowing and transcendent while the baser manipulations rode the subconscious looking for spaceships. Was Sun Ra’s elsewhere, his other-world and alter-destiny a trauma response? Yes. But he was countering the trauma of submission to the tenets of mundane life in the West, opposing the bleakness of beige and gray that the mundane conjured. He did come from or visit Saturn, but telling us was a threat, not self-aggrandizement — a macabre promise that Earth is a primitive planet.

“The darkness is my home,” he confessed at Widney. But you can be afraid of your home and your own nature. You can flinch at the intimacy and invasiveness of your own power. You can doubt you exist because you and the outer darkness are one. “This planet is not my home,” Sun Ra once chanted. It’s brave to denounce the space you inhabit but this is the Los Angeles way. Sun Ra also told us: “I’m dealing with the myth that I’m an angel,” and in the City of Angels, for one night, he became a hostile exile and assumed his Luciferian duty, impersonating his detractors to capture the last of the light. Improvising a theater of rage that swung out like light rays — jaded, autocratic music illuminated by love and vengeance.

For Image, the photographer and filmmaker created a three-minute dedication to herself and her ancestors which she calls ‘a meditation on the reclamation of one’s own freedom.’

You cannot beg a god for forgiveness, but you can be ready when he hints at offering it after a long standoff and not miss the subtle glimmer of that ritual of return, the final shore of a 50-year night.

Harmony Holiday is a writer, dancer, archivist, filmmaker and the author of five collections of poetry including “Hollywood Forever” (Fence Books, 2017) and “Maafa” (Fence Books, 2022). She curates an archive of griot poetics and a related performance series at L.A.’s music and archive venue 2220 Arts + Archives, a space she runs with friends. She has received the Motherwell Prize from Fence Books, a Ruth Lilly Fellowship, a NYFA fellowship, a Schomburg Fellowship, a California Book Award, a research fellowship from Harvard and a teaching fellowship from UC Berkeley. She’s currently working on a collection of essays for Duke University Press and a biography of Abbey Lincoln, in addition to other writing, film and curatorial projects.

More stories from Image