Mexico City’s art scene is booming, but even with deep roots, political uncertainty keeps it fragile

On a warm Friday evening, as the sky begins to turn a shade of orange sherbet, several dozen people decked out in trim suits and stylish dresses train their cellphones on a mound of garbage behind the Centro Citibanamex on the western flanks of Mexico City.

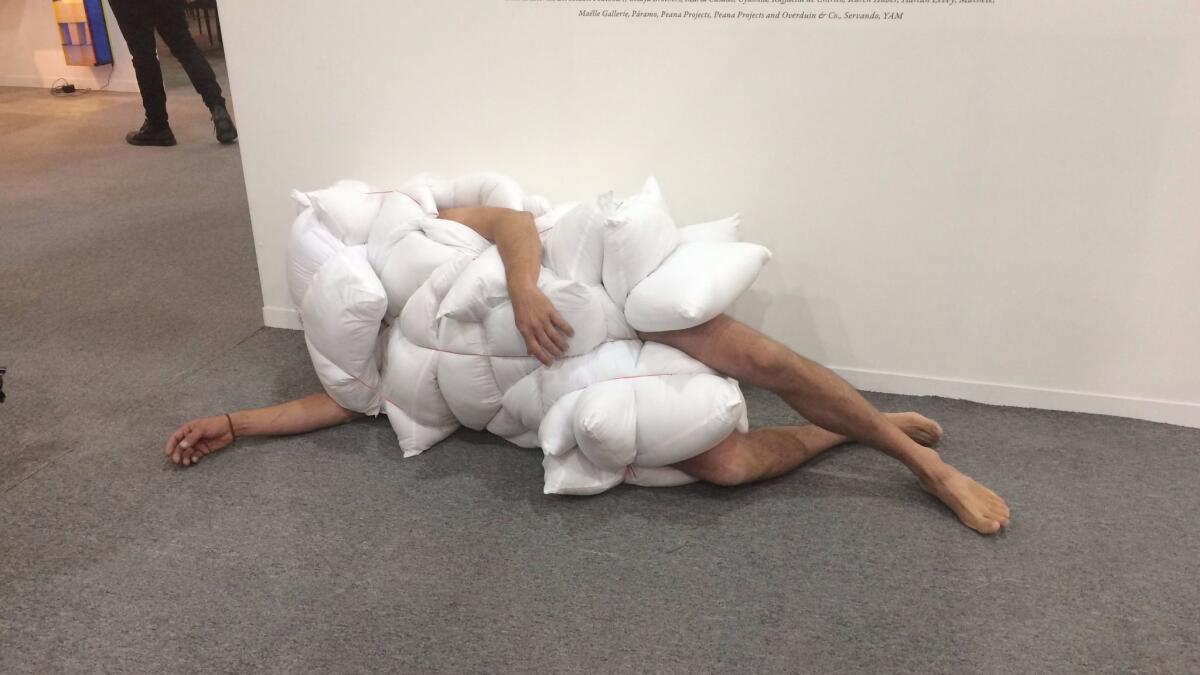

Inside the sprawling convention center is the Zona Maco art fair, featuring art and design from more than 160 international exhibitors. Outside by the loading area, the crowd of artists, curators, collectors and museum directors has gathered to watch a performance by Regina José Galindo, the Guatemalan artist known for staging visceral actions that grapple with issues of impunity and violence. (She once carved the word “perra” — bitch — on her leg, in a performance that protested violence against women.)

------------

For the Record, June 2, 12:45 p.m.: An earlier version of this story reported that Regina José Galindo’s performance took her throughout Mexico City for 15 minutes. She was in transit for about half an hour.

------------

Inside a garbage bag is Galindo herself.

A garbage truck pulls up and the crowd falls silent. A pair of sanitation workers jump out and place the bags, including the one containing the artist, into the truck’s rear loader. A murmur of concern rolls through the crowd.

“Are they going to turn on the compactor?” a man behind me asks of no one in particular. “That thing could kill her.”

The sanitation workers climb back into the truck, and with the grinding of gears, set out. A small camera affixed to the loader transmits a live feed of the garbage to a meeting room inside Zona Maco. There, a handful of the fair’s attendees watch Galindo’s twitching body, shrouded in black plastic, on its journey through Mexico City.

The performance, which was organized by L.A.’s Getty Foundation, evokes the nameless bodies that all too regularly turn up in Mexican garbage dumps. And it perfectly encapsulates the moment that Mexico City is living — a great cultural apogee amid great political and social strife.

Even as violence has saturated the country — federal statistics show that homicides jumped 22% from 2015 to 2016 and 35% the year prior — the Mexican capital, some of its neighborhoods insulated from violence by money and private security, has grown as an international cultural magnet.

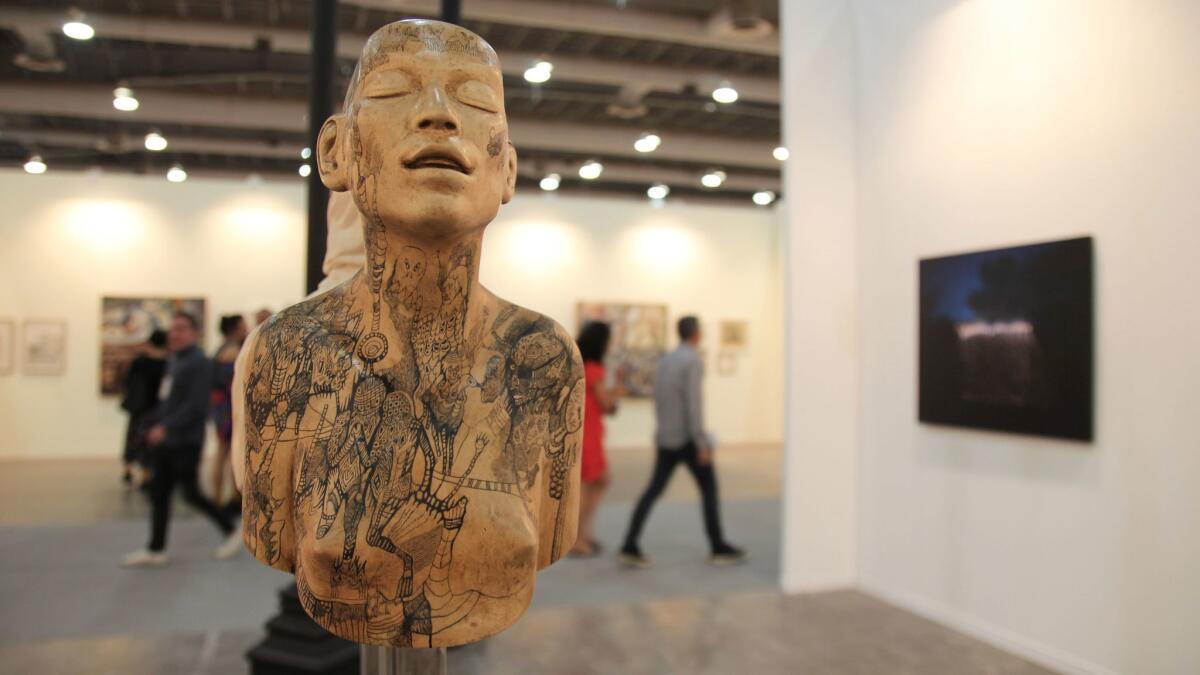

In fact, in recent years, Mexico City has become a regular pit stop for the art-world jet set, part of an international calendar that includes biennials in Europe and art fairs in Hong Kong.

“Galleries have multiplied, as have exhibitions and independent art spaces, as well as fairs,” says Sol Henaro, a curator at the Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo, more universally known as MUAC. “So right now the external gaze on Mexico City has surged.”

MUAC, now almost 10 years old, with a focus on contemporary art, is one of an assortment of new museums that have landed in the city over the last decade. There is also the Soumaya, a torqued, glittery pod that opened in 2011, which features the personal collection of telecommunications mogul

And debuting in 2013 was the contemporary art-focused Museo Jumex, which was established in part by Mexican juice magnate Eugenio Lopez Alonso. Lopez is also a board member on the Museum of Contemporary Art Los Angeles, marking one of the ongoing connection points between Mexico City and L.A.

On top of all that is a rise in internationally visible galleries — the long-running Galería OMR, as well as Proyectos Monclova and Kurimanzutto, which got its start in a pair of stalls at a Mexico City vegetable market in summer 1999 and today represents globally recognized figures such as Gabriel Orozco, Abraham Cruzvillegas and Jimmie Durham. (Durham, a U.S.-born artist, was recently the subject of a career retrospective at L.A.’s Hammer Museum.)

And then there are the art fairs, which turn the humming Mexican art scene into a raging art party every February.

The young and scrappy Material Art Fair, first launched in 2014, drew 15,000 visitors over a four-day period this winter. The tonier Zona Maco, which debuted in 2002 with 25 exhibitors and 3,000 visitors, this year featured 163 exhibitors — including blue-chip spaces such as L.A.’s Regen Projects and New York’s Sean Kelly Gallery — and drew a record 60,000 visitors.

This makes the fair one of the most important in Latin America — and, in terms of attendance, puts it within shouting distance of the glitzy, media-saturated Art Basel Miami Beach, which drew 77,000 people to its latest iteration in December.

“[The writer] Carlos Monsivais once said that whoever was bored in Mexico City was bored of living,” says Kurimanzutto co-founder José Kuri, as he stands before a wall installation by Cruzvillegas at Zona Maco. “The art infrastructure, the ecology, has become really developed. Galleries, artists, museums — everyone — is responding to the new reality.”

Mexico has a complex and vibrant scene historically. Contemporary art is not a new phenomenon here.

— Yoshua Okón, artist

The intensity of the current scene has resulted in a lot of breathy media dispatches that liken the city to “the new Berlin” or “the next Paris,” with at least one British travel dispatch helpfully noting that “the days of Mexican art meaning explicitly Mexican subject matter (such as cacti or sombreros) seem over.”

Overlooked in the Mexico City-as-the-latest-hot-art-thing is the city’s century-long history as an influential cultural and media capital.

“Mexico City has always been on the map,” says Julieta Gonzalez, the chief curator and acting director at Museo Jumex. “It has a long tradition of connections with intellectuals around the world since the ’20s. Maybe some millennials are discovering it now.”

Seismic awakening

Throughout the 20th century, the city has been at the heart of key movements that have shifted artistic landscapes within Mexico and beyond.

This includes muralism in the 1920s, which launched painters such as Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco (no relation to Gabriel) and David Alfaro Siqueiros; the Generación de la Ruptura (Breakaway Generation), which focused on abstraction and produced esteemed painters such as Francisco Toledo and Lilia Carrillo in the wake of World II; and the artists of the 1980s Mexicanismo movement, who toyed with symbols of Mexican identity and popular culture.

“There are a lot of misconceptions about Mexico,” says Yoshua Okón, an artist who runs SOMA, an arts nonprofit that also functions as a free art school. “Many people don’t even know that Modernism happened in Mexico. And Mexico’s Modernism was as vibrant as any in the U.S. or Brazil. A lot of the European avant-garde also went to Mexico.”

Mexico, after all, was home to groundbreaking Modernist architects such as Luis Barragán and the German-born Mathías Goeritz.

“Mexico has a complex and vibrant scene historically,” Okón says. “Contemporary art is not a new phenomenon here.”

As with all artistic moments, the current boom was hardly born yesterday. In fact, Mexico City’s flourishing scene is rooted in a chain of events that, in some ways, reach back to the ’60s.

In fall 1968, in an incident that still haunts the country, the military massacred an untold number of students who were protesting Mexico’s then-upcoming Summer Olympics in the neighborhood of Tlatelolco.

What followed was a period of repression and cultural isolation. In the name of preserving “national culture,” for example, rock music was essentially banned under the presidency of Luis Echeverría.

“People called it la dictadura perfecta — the perfect dictatorship,” Okón says. “It was dictatorship disguised as a democracy and it was very oppressive.”

But the Mexico City earthquake of 1985 shook the country awake. The magnitude 8.1 temblor leveled great portions of the capital and left an estimated 10,000 people dead. Government response was so inept, citizens banded together to dig themselves out of the wreckage. International organizations swept in to help.

These political events infused the art scene with an interest in the outside world.

“Artists like Yoshua Okón and Miguel Calderón, they started to go do their graduate studies at places like UCLA and other schools — they began to develop other contacts and references,” says Henaro of the MUAC. “And you had curators like Cuauhtémoc Medina [now the influential chief curator at MUAC], who was doing his PhD in England, and later became a curator at the Tate for Latin American art. So there are a series of factors that lead people to begin to turn their attention towards Mexico.”

The earthquake also infused the artists of the ’90s with a keen DIY. attitude. Painting, particularly abstract painting infused by Mexican history, was what dominated in institutional settings. But a surge of artist-run spaces rose to engage art forms beyond that: avant-garde video, experimental music, performance and conceptual art.

“The spirit was that if the government cannot fulfill our needs, we will take matters into our hands,” remembers Okón.

Carlos Monsivais once said that whoever was bored in Mexico City was bored of living.

— José Kuri, co-founder of Kurimanzutto gallery

Okón was one of the founders of La Panadería, which ran from 1994 to 2002 in an old bakery in the Mexico City neighborhood of Condesa. (Though Condesa is today filled with high-brow cafes and restaurants, back then the neighborhood was still moribund in the wake of the earthquake.)

For one show, Calderón printed out his artistic résumé as a massive carpet, which a maid then continuously vacuumed — a comment on artistic ego. In another, Teresa Margolles (who has since had her work featured at the Venice Biennale) poured fresh cement made with water used to wash corpses all over the gallery floor.

“One of the agendas behind La Panadería was to build a bridge with the outside,” says Okón. “We started inviting artists, writers from abroad. In turn, we started also getting invitations.”

Spaces such as La Panadería and the also-defunct Mel’s Café and Temístocles 44 brought together artists and curators from Mexico and the world. In the meantime, European art fairs and institutions began to recognize the work of Mexican artists — including that of Conceptualist Gabriel Orozco (roughly a decade older than the ’90s generation), who caused a sensation at the ’93 Venice Biennale for presenting nothing more than an empty shoe box.

The spotlight was on Mexico City. A spotlight that has only grown bigger since.

“It exploded,” says Pilar Tompkins Rivas, the director of the Vincent Price Art Museum in Los Angeles, who has been traveling to the city since 2005. “There have always been incredible galleries, incredible artists and amazing museums, and then the fairs helped draw people in.”

A culture bubble

This flourishing moment, however, rests on top of a fragile political situation.

Mexico City, with its cafes and its galleries and its raging gastronomic scene, is removed from some of the country’s endemic violence, much of it tied to narco-trafficking — with more than 93% of all 2015 crimes going unreported or uninvestigated. Journalists, especially those who dare cover the drug trade or corruption, are frequent targets.

And there is economic uncertainty. In late January, just as the art world was preparing to descend on Mexico City for the art fairs, thousands of Mexican citizens took to the streets to protest a dramatic rise in gas prices that stemmed from the recent privatization of the oil industry. The gasolinazo protests, as they are known, resulted in the arrests of hundreds and several deaths.

The country also faces an uncertain political election in 2018. Not to mention the politics of the Trump administration with its talk of border walls and renegotiating the

It’s a bubble. In Mexico City ... we don’t always notice what’s going on in other parts of the country.

— Mauricio Cadena, director, Parque Galería

Magali Lara, an artist who lives and teaches in the city of Cuernavaca, about 90 minutes south of the capital, says the wealthier part of Mexico City (where much of the arts infrastructure is located) is one universe — the rest of the country another.

Seated at a cafe in the upscale Roma neighborhood, she tells me, “Yes, I come here for two days and I have a great time. But in Cuernavaca, you feel it. There is a pressure. You know what’s there — that there is a certain schizophrenia.”

“It’s a bubble,” says Mauricio Cadena, director of Mexico City’s Parque Galería, a young gallery that represents a crop of U.S. and Mexican artists who often reflect a sociopolitical bent in their work (including Okón). “In Mexico City, there has been economic and cultural progress, to the point that we don’t always notice what’s going on in other parts of the country.”

Certainly, standing in the middle of a buzzing art fair, the violence can feel almost abstract.

“I think people are fed up,” he adds. “In art and culture, our responsibility is to dialogue about this.”

Later that day, the beeping garbage truck pulls up to the loading zone at Zona Maco and picks up Galindo in her garbage bag shroud. It’s a nod to all that is happening beyond Mexico City’s tonier confines.

Except it has a happier ending. After about 30 minutes of tooling around Mexico City, the artist is safely retrieved from the back of the truck. The compactor was never turned on.

Sign up for our weekly Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

ALSO

As Trump aims to build a wall, Los Angeles architecture school SCI-Arc builds bridges to Mexico

Sculpture of a gallows by L.A. artist in Minneapolis may be removed after Native American outcry

The naked guy at graduation is just one of Steven Lavine's memories from 29 years of running CalArts

Meet Robin Bell, the artist who projected protest messages onto Trump's D.C. hotel

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.