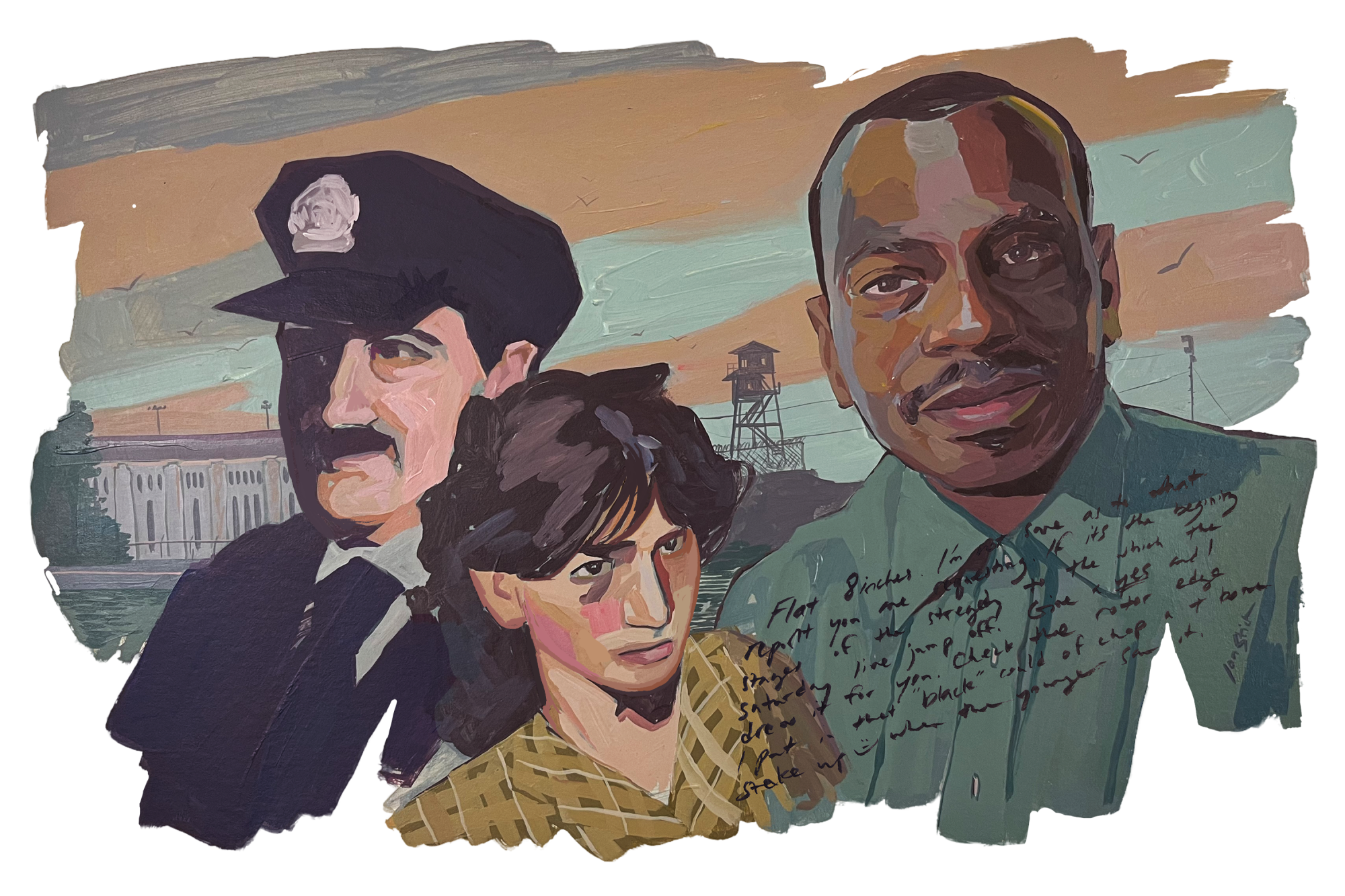

Jarvis Jay Masters says he knew little about the murder of a correctional officer two levels below his cell in San Quentin State Prison. But then another inmate — his superior in the violent Black Guerrilla Family gang — ordered him to copy a set of notes detailing the deadly conspiracy.

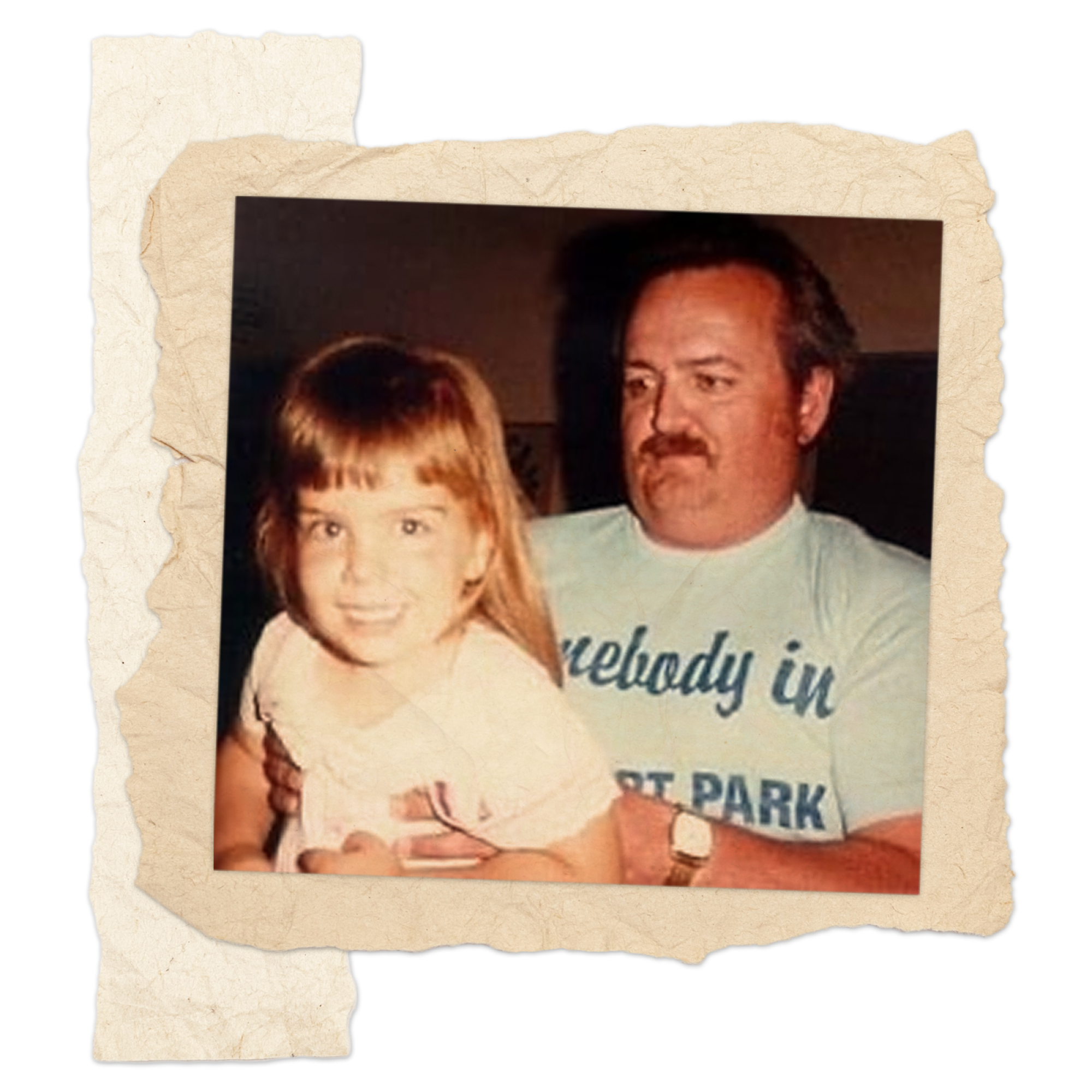

Marjorie Burchfield says she found out about the murder from a knock at the door, a hushed conversation and her stepmother’s wails in the middle of the night. She didn’t need details to know her father was dead.

It was June 1985, and correctional Sgt. Hal Burchfield, a 37-year-old father of five, had been stabbed in the chest while making rounds at the state’s oldest and most notorious lockup on San Francisco Bay.

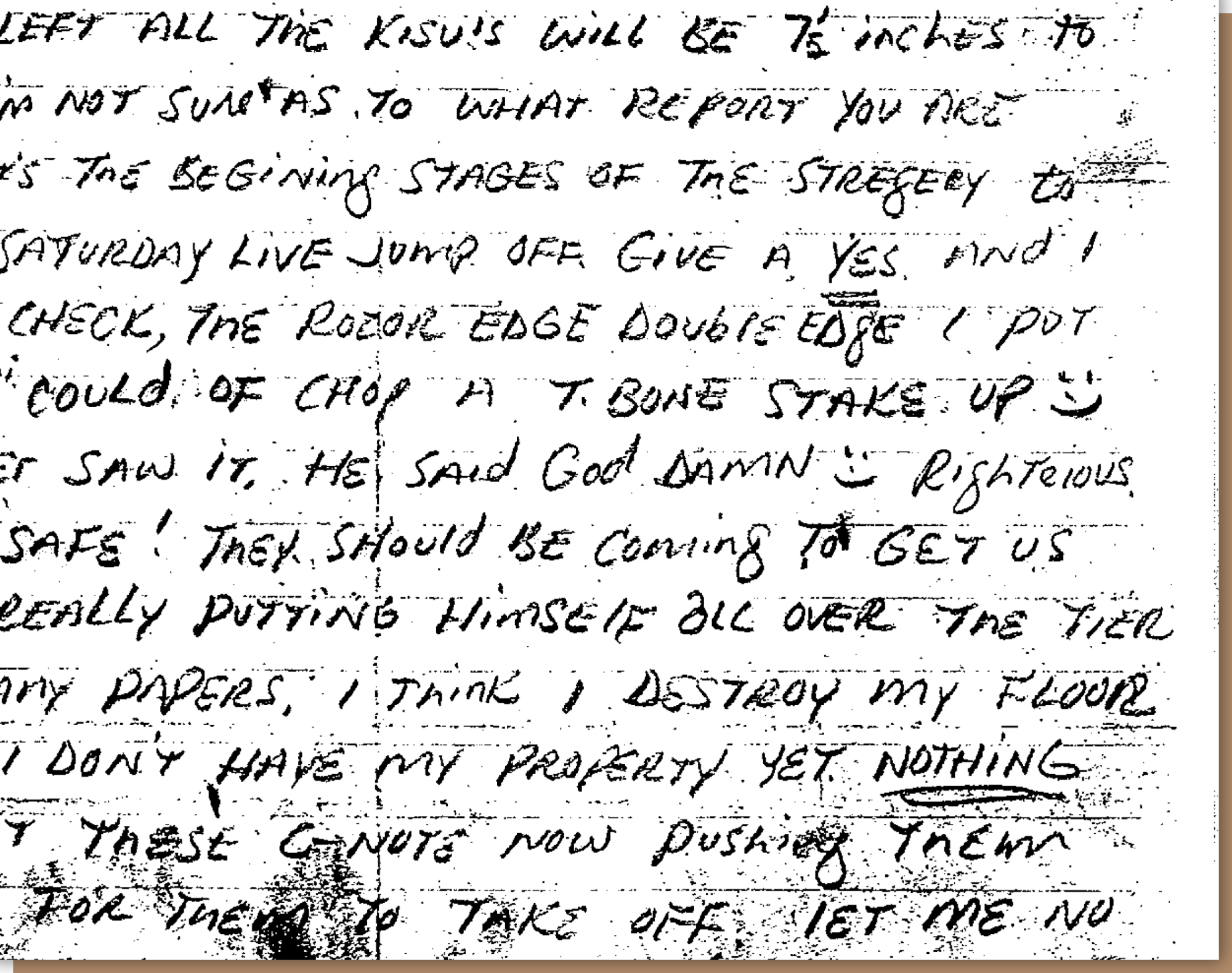

Inmates would later describe the weapon as a San Quentin special: a piece of metal bed frame, sharpened and attached to the end of a makeshift spear formed from tightly rolled newspaper. One of the notes Masters says he copied — known as “kites” for the way they are thrown between levels on string — bragged, with a smiley face, that the spear’s tip was so sharp it could “chop a T-bone.”

In the ensuing months and years, the kites, clearly in Masters’ handwriting, would become key pieces of evidence against him in a protracted murder trial that stretched until 1990. At the trial’s conclusion, Masters was convicted of murder and conspiracy to commit murder for his alleged role in making the spear’s metal tip.

Two other inmates and BGF gang members were also convicted of murder, including the inmate who did the stabbing and a BGF leader who ordered it. They both were sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole.

Masters was sentenced to death.

Now, more than three decades later, the kites are once again at the center of a looming legal challenge as Masters, now a reflective 60-year-old Buddhist and author, once again tries to clear his name.

In November 2020, Masters appealed his conviction and sentence for the first time in federal court, after years of state judges — including those on the California Supreme Court — rejecting his claims of innocence.

A federal judge this month said he would issue a written decision in the case, which could come any day.

In addition to the kites and competing claims as to their origin, evidence to be considered includes recantations by the inmates who accused Masters of being involved in the murder at his trial, as well as confessions from others who say they made the spear tip that Masters was convicted of crafting.

For Masters, the federal case is a final chance to convince the world he is not a monster deserving of death, but an innocent man being deprived of life.

For Marjorie Burchfield and her siblings, it is a reminder of the most disruptive event of their young lives, one that has forced them to revisit decades of emotions, memories and beliefs — not only about the murder and Masters, but also about their father and the boundaries of justice, mercy, family and redemption.

Attention on the case has surged in recent months because of the discrepancies in the evidence, but also thanks to Oprah Winfrey, who helped connect Masters with a new team of powerhouse pro bono attorneys and last month picked his 2009 autobiography, “That Bird Has My Wings: The Autobiography of an Innocent Man on Death Row,” for her influential book club.

In a series of recent phone interviews with The Times, Masters said that while he awaits the federal judge’s decision, he is trying to protect his sanity the Buddhist way, by staying in the “middle” mentally — neither convincing himself that this will finally be the appeal that succeeds, nor that it is destined to fail like all the others.

Still, he can’t help but be a little optimistic.

“I feel like now I’m in good hands,” he said. “Now my case can get some speed to it, get some traction.”

Winfrey, until now, has carefully avoided making definitive pronouncements about the facts in the case — saying in her glowing reviews of Masters’ book only that he says he is innocent.

But, in an interview with The Times, she said she “absolutely” believes he is innocent, and wouldn’t have selected his book if she didn’t.

Burchfield’s children are not of one mind.

Burchfield’s youngest child, Jeremiah, who was 2 when his father was killed, said he has studied the case, fully believes in Masters’ innocence, and plans to advocate for his freedom.

“Sometimes the judge just looking at the support of the victim’s family does help,” he said.

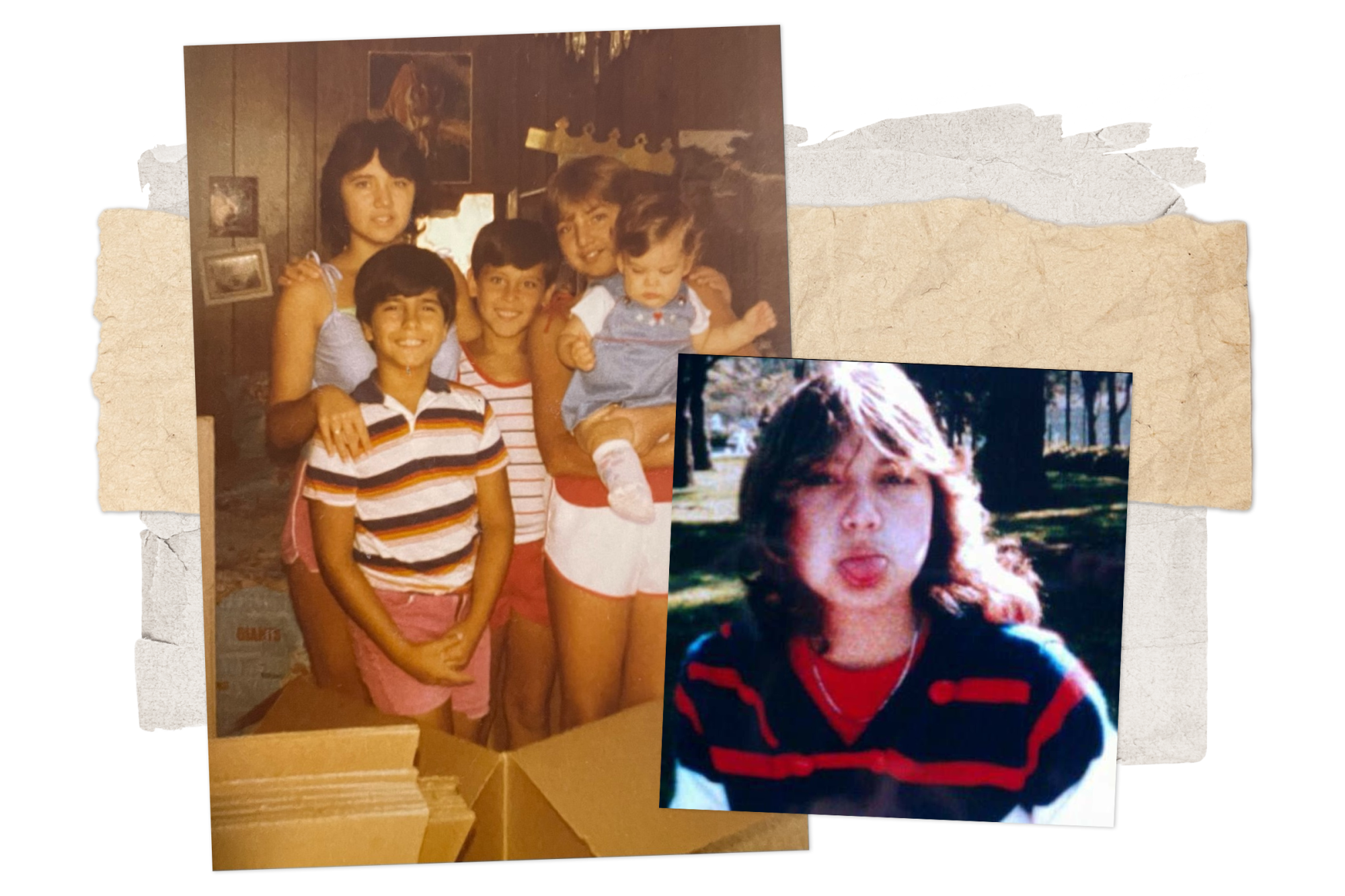

Marjorie Burchfield, who was 14 when her father was killed, says she spiraled out of control after the murder and was homeless and addicted to drugs for years as a teen before enlisting in the U.S. Army and later becoming a correctional officer — just like her dad.

The murder, she says, destroyed her childhood.

She has never stopped believing in Masters’ culpability and hopes he remains behind bars for good if California’s moratorium on executions continues.

“You can ask for forgiveness. You can become a Buddhist. I don’t care [if] you were the pope,” she said. “You did the crime, you have to pay.”

Masters was born in Long Beach, and into a horrific childhood.

By the time he landed in San Quentin for armed robbery at age 19, he had been traumatized and neglected by his violent father and addicted mother, beaten and abused by his subsequent foster parents, ridiculed and forced to fight other kids by overseers in state-run youth facilities, and drawn into a life of crime by older relatives and their friends.

Masters was 23 when Burchfield was murdered, and would spend the next 21 years in segregated and near-solitary confinement under the premise that he presented a danger — or would be in danger himself — if he were allowed to mingle with other inmates. He increasingly turned inward, he said, discovering Buddhism and a talent for writing.

He wrote the autobiography Winfrey now touts with only the inner filler of a pen, because he wasn’t allowed the hard outer casing lest it be fashioned into a weapon. His writing hand at times would ache, he said, but processing his turbulent life’s stories helped him rise above the anger they evoked.

Subscribers get exclusive access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers special access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

During his trial, Masters said he believed he was getting off. Surely the jurors would perceive his innocence, he thought. They’d see that, for all his faults, he was no murderer.

“I was a bandit, I was a crook, I stole, I robbed people. I did a lot of stuff,” he said, “but not that.”

However, presented with testimony from other inmates who said Masters was involved and had confessed to his part, and shown the kites in Masters’ handwriting, the jurors did convict him. They also sentenced him to death, which prompted an automatic review by Marin County Superior Court Judge Beverly Savitt, who was presiding over the case.

Prosecutors pushed Savitt to uphold the sentence, pointing out Masters’ criminal record and suggesting he was guilty of other violent crimes that he had never been charged with.

Masters’ defense argued for leniency, citing the horrors of his childhood, his relative youth and his recent good behavior in prison. “There must be a place in our jurisprudence that allows for compassion,” said Michael Satris, Masters’ attorney at the time.

Savitt, who could not be reached for comment, responded with a striking speech from the bench.

The death penalty “happens to be a law I disagree with,” she said, but California voters had approved it, and it was her “duty” to follow the law.

She praised Satris for putting forward strong arguments for reducing Masters’ sentence, saying he had turned his client “into a human being” for her and the jurors.

Then she turned her focus on Masters. He was “born into hell,” she said. It was “almost impossible” for her to understand why he was born in the first place. “If people don’t want children,” she added, “they shouldn’t have them.”

Savitt said she understood — at least to the extent that “one who was raised white middle class” could — what “created Jarvis Masters” and “turned him into a violent person.” But she also had to consider that others who grow up in similarly “miserable” environments don’t turn violent and that Masters had a choice to do better but instead “gave up on himself.”

“I have to conclude,” she said, “that the verdict of the jury of death must be upheld.”

Masters said he was wounded by Savitt’s decision, which was very different from the one she made after the trial of the inmate who actually stabbed Burchfield. The jury had condemned him to death — but she decided to spare his life.

“When the judge said that I should not have been born before she sentenced me to death, it said something more to her reasons why she gave me the death sentence and no one else,” Masters said. “I’m glad my mother gave me a chance to live.”

Masters has seized that chance despite his confinement in San Quentin.

Through his devotion to Buddhism and a growing body of published essays online, he attracted a group of admirers on the outside. Buddhist luminaries now visit him as friends. He has married and divorced from prison, rekindled ties to some of his family, had a book written about him and written two books of his own. Winfrey recently interviewed him by phone for a book club chat, because even Oprah can’t get an on-camera interview in San Quentin.

Pictures of Masters from over the years, all taken by guards on behalf of his visitors because that’s the only permissible photography there, show an easy smile, a gap between his two front teeth and graying in his neat goatee. He wears a blue prison shirt in each, buttoned down with a collar.

Having requested but never received approval to visit Masters in person, The Times spoke to him over the course of two 45-minute interviews, also by phone, each of which were split into 15-minute increments by the San Quentin phone system.

During those calls, Masters was open about his transgressions as a teenager and adamant about his innocence in Burchfield’s murder. He seemed to reflect on his life with a detached, philosophic gaze, partly a defense against the harshness of his reality.

He also, somehow, has retained his sense of humor — something Winfrey noticed too.

“I was fascinated at how normal he is, and how coherent and present he was, because that would be a struggle for, I think, most people — to hold on to yourself in the midst of that,” she said. “I know that I would not be capable of doing it.”

When asked what it is that has allowed him to fare so well in such dire circumstances, Masters at first demurred. But he later talked about a conversation he had with his sister years ago. He was obsessing over his prison life — how he’d performed in a basketball game, how he’d navigated certain prison-yard politics — and she stopped him abruptly.

“What about us?” she asked. He never wrote his family. Did he care?

Masters said he realized then that he had ceded too much of the outside world. To remain himself and stay afloat in San Quentin’s riptide of misery, he had to stay focused — not on the same prison scenes day after day, but on the big, diverse world beyond the prison walls.

To this day, Masters said his greatest hope is that he will one day rejoin that bigger world, and that those in it will still be able to recognize him as “a human being” — something he hasn’t felt since being condemned to death.

“The only way you can put somebody on death row is you got to dehumanize them. They cannot be a human being,” Masters said.

“They have to be considered an animal, a beast, a mass murderer, a savage.”

Marjorie Burchfield, now a straight-talking 51-year-old retired correctional officer who still works security gigs to pay the bills, says she wishes her dad had more of a chance to become the father figure his five kids needed.

On the night of the murder, Marjorie and her siblings were with their stepmother visiting friends in Sacramento. She and some of the other kids were sleeping downstairs, “so we heard the knock,” she said.

She’s not sure how the cops — or were they other correctional officers? — had found the family that night, but suddenly there they were, like military officials in old war movies who arrive on a soldier’s porch to tell his widow he’s dead.

Marjorie heard their hushed tones, and her stepmother’s wails, and she thought of those movies and knew her dad was dead, she said. “There’s something deep inside you. ... You just kind of know.”

After that, she said, everything changed.

Five childhoods were upended. She still thinks about that whenever she hears Masters’ supporters, including Winfrey, talk about his troubled childhood.

“We’ve been through the exact same thing,” she said.

Sgt. Burchfield was a strict disciplinarian. He was smart, kept a diary, was always reading, and was very religious, allowing his kids to listen to Christian albums but never the radio.

He was also a “harsh and violent man” who beat his children, said his son JD Burchfield, who was 12 at the time of the murder.

Marjorie said her father “was stern like many fathers in the ‘80s,” spanked his kids for misbehaving and would “slap you across your face if you talked back.” If they misbehaved more seriously, she said, they would “get an ass whupping.”

The large family lived solely on their father’s salary, and the kids knew money was tight. They were also aware that his work played a big part in shaping what mood he would be in when he got home.

“Sometimes he’d come home with blood on him,” Marjorie said, “or sometimes he’d be just so crabby.”

He would tell the kids terrifying stories from San Quentin and show them Polaroid pictures of inmates who had been bloodied and badly injured in fights, she said. Other times, he would lash out at them seemingly without reason.

Like his sister, JD, now a 49-year-old human resources director at a Seattle college, remembers the night of the murder vividly. He said he was sleeping downstairs with Marjorie and realized their father was dead about the same time she did. But he had a completely different reaction: His father’s death meant, first and foremost, that the beatings would stop.

“I don’t know if I’m ashamed of this or not, but I’ve never been so relieved in my life,” he said. “I’d been afraid for most of my childhood, and that was the night I wasn’t afraid anymore.”

In the immediate aftermath of the killing, Burchfield was lionized, and his murder was used by the powerful California Correctional Peace Officers Assn. as an example of the dangers that correctional officers faced and another reason they deserved more resources.

Why Burchfield was targeted by the BGF remains an open question, though BGF members have alleged it was because he was supplying weapons to inmates in the rival Aryan Brotherhood. Corrections officials said they could not say whether those allegations were ever probed because investigations of staff misconduct are confidential, but that colleagues held him in “high regard.”

Burchfield’s kids say they don’t know what to believe about why their father was killed, though Marjorie believes inmates lie and will say anything to get out of trouble.

She also excuses much of her dad’s violence as a reflection of the times they were living in, and as “tough love” from a concerned father who had seen society’s worst criminals and wanted to keep his own kids out of trouble.

“I would have never survived on the streets if it wasn’t for him.”

When her father was killed, Marjorie was completely unmoored, she said. She could no longer handle living with her stepmother, who she alleged was also abusive. She and JD moved out not long after the murder and tried living with their mother, but she had her own problems, they said, and that was short-lived.

When JD decided to return to their stepmother’s home, Marjorie refused. Instead, for the next few years, she floated around Sacramento, couch-surfed and slept for a while behind a McDonald’s, where she’d fallen in with other homeless teenagers and adults, eating from the dumpster every night. She started doing drugs, and began committing petty crimes to survive, she said.

Finally, at 18, Marjorie said she realized she couldn’t keep living on the streets and bouncing around friends’ homes. So, summoning the discipline she credits her father with instilling in her, she joined the National Guard and then the Army.

Years later, when she got out and decided to become a California state correctional officer just like her dad, it was with one goal in mind, she said.

“At that time I was still angry and it was my whole life ambition to go and retaliate against Masters and the whole group.”

To convict a person of murder and sentence him to death, a jury has to be sure, beyond a reasonable doubt, that the person is guilty.

In the years since Masters’ conviction, an array of doubt has been raised.

His attorneys have hired expert linguists who determined, by comparing the kites to Masters’ other writings, that they were indeed authored by someone else, even if Masters had transcribed them.

In court filings, Masters has said he was ordered to copy the notes by another BGF leader named Rufus Willis. Willis had come forward to the authorities after Burchfield’s murder and offered to testify against his fellow BGF gang members if he was granted immunity in the killing — which he received.

Masters claims Willis falsely identified him as being involved in the murder because he had recently fallen out with the gang. He also claims an investigator with the Marin County district attorney’s office then urged Willis to collect more evidence against Masters, which Willis did by ordering him to copy the kites.

Masters feared for his life and couldn’t disobey Willis’ orders because inmate attacks were prevalent at the time. BGF members swear a blood oath to follow orders or face repercussions.

Beyond the kites, there are the recantations and confessions.

Willis, who ended up serving as the state’s star witness in Masters’ trial, has since recanted his testimony that Masters was involved.

Another inmate named Bobby Evans, a well-known informant, had corroborated Willis’ testimony at trial, alleging Masters had confessed his role in the murder to him. Evans has also since recanted, saying his earlier testimony was a lie.

In August 1986, just over a year after Burchfield’s murder and long before Masters’ conviction, an inmate named Harold Richardson met confidentially with a program administrator at San Quentin to discuss his desire to get out of the BGF. During those meetings, which administrator J.S. Ballatore described in contemporaneous memos to a deputy warden, Richardson allegedly said that others had prepared and he had sharpened the piece of metal that killed Burchfield — not Masters.

Ballatore wrote that Richardson “appeared sincere and truthful” during the interview.

Richardson’s confession was available at the time of Masters’ trial but never admitted as evidence. During his state appeal, it was ruled to be unreliable hearsay.

Years later, in 2001, yet another inmate, Charles Drume, signed a sworn affidavit claiming that he had made the weapon used in Burchfield’s murder, and that Masters was innocent.

Masters has filed many appeals in state court over the years, to no avail.

In 2008, the California Supreme Court found there were enough legitimate legal questions surrounding Masters’ conviction and death sentence that a special judge should be appointed to conduct a fresh review of the facts and report back to the high court.

In 2011, then-Marin County Superior Court Judge Lynn Duryee produced that report.

Duryee found that many inmates involved in the incident had lied at some point, that some had recanted and un-recanted multiple times, and that all of the BGF gang members providing statements or testimony in the case in more recent years had a motive “to give testimony favorable to Masters.”

She noted there was “no agreement” between the many inmates on “fundamental facts,” and that some of their claims contradicted one another.

Duryee found that even though it was likely some false evidence had been presented at Masters’ trial, the jury had been given the chance to “evaluate the believability of the testimony of the witnesses.”

And, while noting that “key trial witnesses” Willis and Evans had both recanted, Duryee said she had “scant ability to discern whether they are lying now or whether they were lying then,” and could “only find that Willis and Evans are both liars with highly unreliable and selective memories.”

In other words, Duryee concluded — through a bit of legal logic that has infuriated Masters’ supporters ever since — that although Masters was convicted and sentenced to death based on the word of Willis and Evans, their word “means nothing” and he could not be exonerated based on the same.

The California Supreme Court has since denied all of Masters’ appeals, saying it largely agreed with Duryee’s conclusions. It found Evans and Willis weren’t credible, that the jury already had a chance to consider their credibility at trial, and that it’s not clear the jury would have ruled differently with the information Masters brought forward on appeal.

“At best, Masters has demonstrated that these witnesses generally are liars, but he does not offer any persuasive reason to credit their recantations over their trial testimony,” Justice Goodwin Liu wrote for the high court in 2019.

Masters’ supporters say it’s inconceivable that he received the death penalty for allegedly making the weapon used in Burchfield’s killing when the inmate who actually did the stabbing got a life sentence. And they accuse the high court of shirking its responsibility to ensure justice is served, not just that technicalities of the law are adhered to.

“I just feel that any reasonable person, reading the facts of this case, would want to at least have the case reopened so that you could at least know that you made the greatest effort for justice to be served,” Winfrey said.

Masters’ defense team makes similar arguments in his latest appeal in federal court, alleging that his initial trial was “riddled with constitutional issues” that the state courts improperly ignored.

His attorneys have cited the recantations and confessions of other inmates, and the testimony of the linguists.

They also have argued the exclusion of Richardson’s confession as hearsay violated clearly established legal precedent from both the U.S. Supreme Court and the U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals that says trustworthy and material evidence favoring a capital defendant may not be excluded based solely on legal technicalities.

“Masters was convicted of the very act that Richardson admitted to,” they wrote.

What the federal court may decide in Masters’ case remains unclear.

Any decision could be appealed to higher federal courts. And, if the courts upheld a decision in Masters’ favor, he could still be tried again for the murder in Marin County, depending on how willing state and local officials would be to relitigate a nearly 40-year-old case.

For now, Masters will remain behind bars, on the first floor of San Quentin, one of nearly 700 current California inmates who have been sentenced to death. He won’t be executed under Gov. Gavin Newsom, who has issued a moratorium on executions, but that order could be lifted by Newsom’s successor.

Marjorie Burchfield, who turned corrections into a career and says she never ended up exacting the revenge she wanted, said she believes Masters is guilty and right where he belongs. She understands why he is still challenging his death sentence — who wouldn’t? — but doesn’t think his arguments are persuasive.

“I don’t think it’s going to work,” she said. “Give it your best shot, buddy.”

JD Burchfield said he doesn’t believe in the death penalty, believes Masters has reformed, and doesn’t see the point in keeping him locked up whether he is innocent or not.

“The reason I oppose the death penalty is because it robs people of a shot at redemption, [which] was the one thing that my father was robbed of: the chance to have an adult conversation with his children,” JD said.

Jeremiah Burchfield, now 40 and working in the cannabis industry, has only a few memories of his father, which are positive, but wonders what their relationship would be like today given what he knows of the abuse his siblings faced.

Both Marjorie and JD are gay. They say their father’s violence was at times sparked by his children’s failure to adhere to gender norms. Jeremiah, who is transgender, says he can’t help but wonder what his father would think of his identity were he alive today. He feels robbed of finding out.

But, he doesn’t believe Masters is responsible for that.

Jeremiah said he had a “nagging feeling in my heart and my gut” about the case for years, which drove him to study it more closely — and conclude Masters is innocent.

He said he recently wrote a letter to Masters apologizing for not speaking out about his case sooner, and said he plans to advocate for Masters moving forward, including in court if necessary.

“A man being cheated of his freedom and being incarcerated without reason isn’t doing my father justice,” he said. “It’s just ignorance.”

Winfrey said her decision to elevate Masters’ story was based on the power of his book — which is largely about his childhood — and the lessons it teaches about the devastating effect that trauma has on children who are deprived of love and subjected to the very worst of the American criminal justice system.

It’s a story, she said, the world needs to hear. “I can’t imagine a greater miscarriage of justice than to be accused of a crime, and knowing that you did not do it.”

For Masters, the idea of getting out of prison after so long is exhilarating — and terrifying, given how much the world has changed since he arrived at San Quentin more than 40 years ago.

“It would scare the hell out of me that I got out,” he said.

Although he has had a few trips while beyond bars, for medical appointments and court hearings, the outside world seems a distant memory. These days he rarely even goes to the prison yard, preferring to remain in his cell and work on preserving his mind by meditating, reading or writing, he said.

He doesn’t know exactly what he’d do if he got out, but he imagines sitting outside at night, something he hasn’t done in decades.

He also wants to get out while he can still understand the world around him, and to be someone on the outside — to others and to himself. Not a monster, but a friend, a brother, an uncle.

“When you are living somewhere where you are just so dehumanized,” he said, “to say I want to be a human being is really to say I want my freedom. I want to enjoy my freedom. I want to be recognizable.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.