Oprah picks California death row inmate’s autobiography for book club

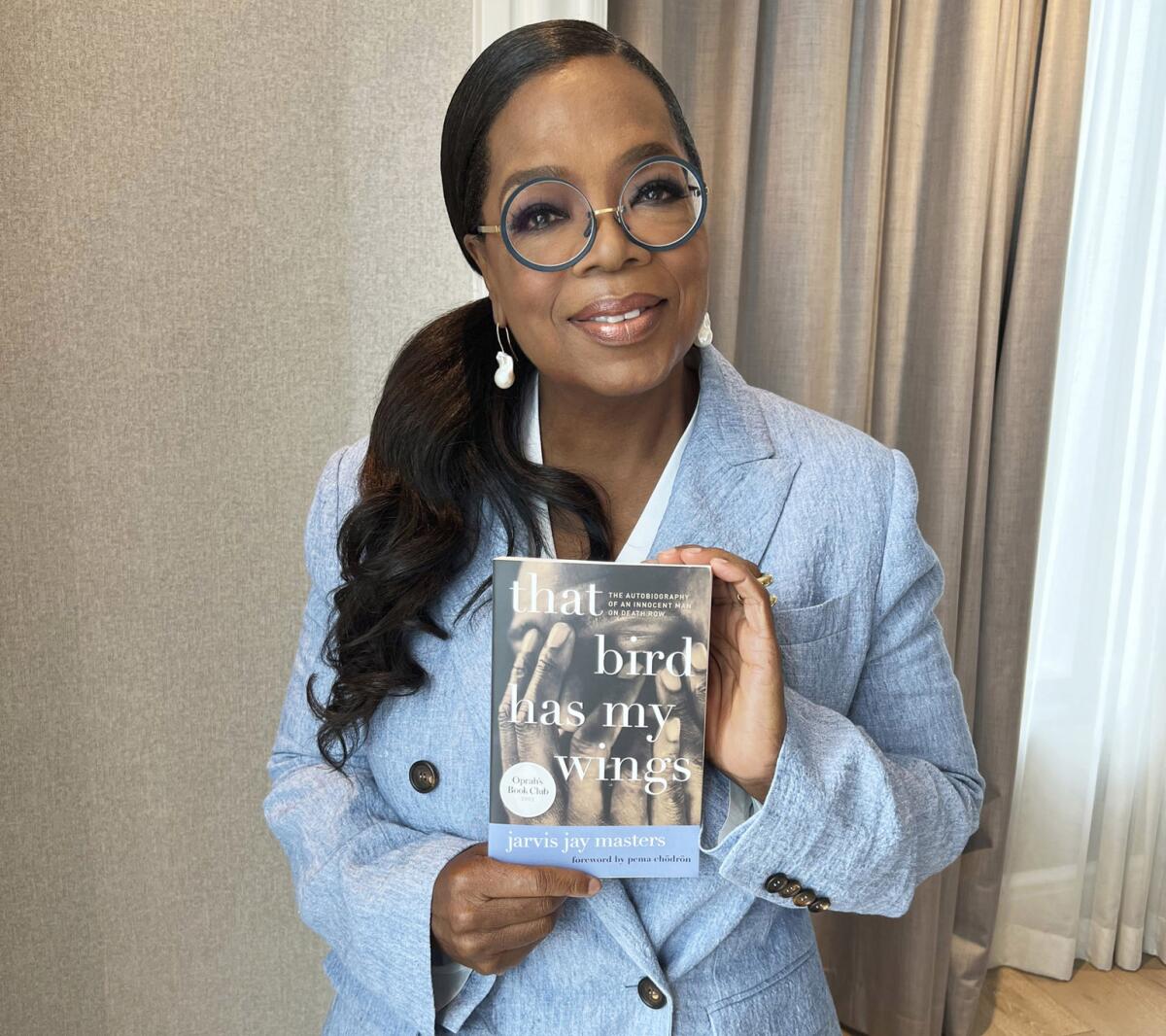

Oprah Winfrey has chosen a California death row inmate’s autobiography — in which he proclaims his innocence — as her influential book club’s next read, she announced Tuesday.

The move was sure to bring immense attention to — and spur sales of — Jarvis Jay Masters’ book, “That Bird Has My Wings: The Autobiography of an Innocent Man on Death Row,” which was first published in 2009 and recounts Masters’ traumatic childhood, his life in prison and his discovery of Buddhism behind bars.

The selection also shines a spotlight on Masters’ ongoing legal battle to overturn his conviction and death sentence in the murder of a correctional officer at San Quentin State Prison in 1985. Masters’ claims of innocence, and new evidence to support them, are set to be heard for the first time in federal court next month, after being rejected in state courts.

Among the children of Sgt. Howell Dean Burchfield, the officer whose 1985 murder Masters was convicted of participating in, the announcement stirred mixed emotions — with Burchfield’s son welcoming it and a daughter denouncing it.

In announcing the selection on “CBS Mornings,” Winfrey said her intention was “to expose the story” and to let people know that there are people on death row “for whom there has been a miscarriage of justice.”

On Instagram, Winfrey called the book “a deft, wise, page-turning account of childhood trauma, his experiences in foster care, his journey through the American justice system, and his spiritual enlightenment while on death row.”

On CBS, she said she was first told about the book around 2014, by Buddhist nun Pema Chodron, a mentor and friend of Masters.

“I read the book, loved the book, wanted to choose the book [for the] book club then, or at least get an interview with him then,” Winfrey said on CBS.

She said that she called then-California Gov. Jerry Brown and that her team “appealed to the entire prison system,” in an effort to get an on-camera interview with Masters, but they were denied.

She did not say why she’d chosen to move forward with the selection now, though the CBS piece on Tuesday went into some detail about Masters’ latest appeal for his conviction to be vacated in federal court.

The CBS piece featured a phone interview with Masters by CBS correspondent David Begnaud, in which Masters told Begnaud that his intention for writing his life story “was to speak to the kids, people who were at risk” of falling into the criminal justice system.

“I saw those faces in that book when I wrote it,” Masters said. “I was telling their story as well as mine.”

He also firmly denied playing a role in the murder of Burchfield, who left behind a wife and five children.

“I never understood why I was charged with it,” he said.

JD Burchfield, who was 12 years old when his father was killed, told The Times Tuesday that he welcomed Winfrey’s recognition of the case and Masters’ search for spirituality and redemption behind bars.

“I’m pro somebody promoting healing in any fashion. I think that’s what she’s trying to do with Jarvis Masters’ story, and I think it’s appropriate and I support it,” he said.

Burchfield, now 49 and a human-resources director, said he has complex feelings about Masters’ situation, just as he did about his father, who he said was a “harsh” and sometimes violent man.

He said he opposes the death penalty in part because it robs people of the chance at redemption — which he believes his father also was robbed of — and sees no reason why Masters should remain in prison given all his efforts toward redemption.

“I don’t know what’s being served by him being behind bars, much less by him being killed,” Burchfield said.

His sister Marjorie Burchfield, 51, who was 13 when their father was killed and later became a correctional officer herself, feels very differently. She said she believes Masters is guilty of the crimes he was convicted of and should never get out of prison.

“He’s not the Buddhist everyone thinks he is,” she said.

She said she was “upset and pissed off” when she heard about Winfrey’s selection, and tried to write to Winfrey directly through Instagram to tell her it wasn’t fair for Winfrey to “choose to back a felon’s book who killed somebody else’s family.”

She said she wonders where the proceeds from the book sales will go and who is making money off her father’s murder.

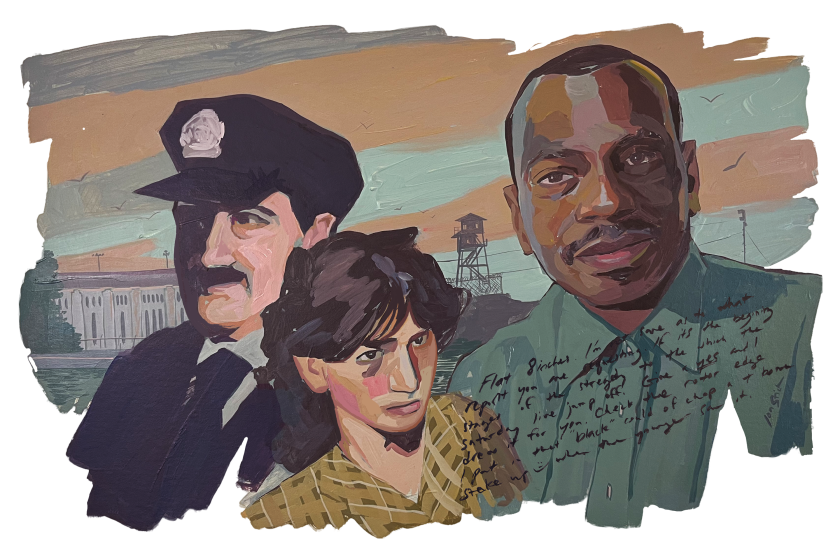

Masters, now 60, was abused as a child, abandoned by his parents and shuffled through the foster care system before eventually landing in San Quentin as a teenager in 1981, for multiple armed robberies he acknowledges committing.

Four years later, while still in prison, Masters was accused of participating in the killing of Burchfield, who was stabbed in the chest while making rounds.

The killing was a planned attack by the Black Guerrilla Family gang, of which Masters was an alleged member. Masters was not accused of stabbing Burchfield but of sharpening the makeshift weapon that was used in the attack.

Another inmate and gang member named Andre Johnson, who stabbed Burchfield, and a third inmate named Lawrence Woodard, who ordered the attack, were also convicted in the murder. However, Masters was the only one of the three to receive the death penalty. Johnson and Woodard were sentenced to life imprisonment without the possibility of parole.

Gov. Gavin Newsom has issued a moratorium on executions in the state, but those on California’s death row could still be executed if the moratorium were lifted.

The case against Masters, who spent years in solitary confinement, was built on the testimony of several other inmates, and on notes outlining the attack that were found in Masters’ handwriting. But much of the case has fallen apart in the intervening years.

The inmates who accused Masters of being involved have recanted. Other inmates have confessed to sharpening the weapon. And while Masters has acknowledged writing the notes, he said he was simply copying out the writings of other gang members — something the BGF was known for having younger inmates do — under orders and threats from gang leaders.

His defense even hired an expert linguist who compared the writing style of the notes against Masters’ own writings and determined Masters did not author the jail notes — even if he had copied them.

The state courts heard some of the above evidence, including in appeals Masters brought after his conviction by a jury at trial, but not all of it. The confession of another inmate was considered hearsay and excluded. A special judge who reviewed the case on behalf of the California Supreme Court dismissed the recantations of others, saying the inmates — the same ones the state had relied on to convict Masters — were liars who could not be trusted.

The California Supreme Court rejected Masters’ last request for relief in 2019. His legal team subsequently filed the federal claim, alleging the state courts had violated his constitutional rights in violation of established U.S. Supreme Court precedents. A hearing in that case is scheduled for next month.

Michael Williams, one of Masters’ pro bono attorneys, said federal law requires states to consider evidence that would help exonerate a prisoner sentenced to death, even if such evidence might otherwise be ignored through technicalities of the law.

Williams said the confession of another inmate, captured in prison records dating back to the time of the attack and dismissed by the state courts as hearsay, fits that category. He said the volume of evidence supporting Masters’ innocence is now substantial, and he should be released from prison immediately.

“I have never seen such an egregious case of injustice,” Williams said. “Exonerating Jarvis is the right thing to do, not only legally but also ethically. Justice is not served until Jarvis is free.”

Williams said Oprah’s selection of Masters’ book “highlights Jarvis’ amazing story of grit and resilience” and “lends an extra layer of visibility” as the case goes to federal court.

California Atty. Gen. Rob Bonta’s office, which is fighting Masters’ claims in court on behalf of the state, declined to comment on the case Tuesday.

A San Quentin State Prison guard’s 1985 murder still ripples through time in the lives of an inmate sentenced to death and the guard’s children.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.