Does L.A. have an ‘addiction to cults and cultists’? Sure seems like it

When powerful professed men and women of God come to grief, they almost always do so over two transgressions older than the Commandments: sex and money.

The leader of the Mexico-based international La Luz del Mundo church pleaded guilty this month in Los Angeles to sexual felonies with underage girls in his church community. The judge who sentenced him remarked, “I’ll never cease to be amazed at what some people do [in the name of] religion.”

The church leader joins the sullied company of the Catholic priests who molested boys and girls in their charge; the accused and convicted sexual abusers on the Southern Baptists’ list of offenders in their own ranks; and the pastors and preachers, low and high, taken to court for making off with anything from thousands to millions of dollars rightfully belonging to God and to their congregants.

These foibles and pitfalls can entice not just orthodox, IRS-blessed religions but also the self-made leaders of spiritual, self-help, self-fulfillment and human potential bodies that have grown here in Southern California as nowhere else. With wonder and delight, the social critic and author Carey McWilliams often pointed out our “fabled addiction to cults and cultists.”

In 1895, an indignant Pasadena lady who gloried in the triple-decker name of Mrs. Charles Stewart Baggett wrote, “I am told that the millennium has already begun in Pasadena, and that even now there are more sanctified cranks to the acre than in any other town in America.”

My dear Mrs. Baggett, it all got a start here at least 50 years before that.

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

In 1841, a Scotsman named William Money — Hispanicized into Mo-NAY, from his years in Mexico, arguing Catholic padres into exhaustion over matters of faith — blew into town and promptly earned $126 repairing the plaza church.

Soon, L.A. learned that menial labor was beneath a man of his prodigious talents, which — just ask him — included astronomy, medicine, law, book publishing, philosophy, the sounds of a conch shell and the habits of muskrats. A man of his destiny, born, as Money said, an infant prodigy, “with four teeth and the likeness of a rainbow in my right eye,” was soon practicing medicine of a sort, which extended to treating patients in an 1860s smallpox epidemic. At the end of his life, he boasted that he had tallied 5,000 patients, of whom only four had died.

He had the distinction of founding the region’s first religious sect, Reform of the New Testament Church, styling himself as Bishop Money, as well as Doctor and Professor Money. He published what is apparently the first English-language publication in L.A.: the exceedingly rare, 22-page “Reform of the New Testament Church,” also produced in Spanish. And he managed to get into official city records an illustration of his “discovery,” a vast subterranean ocean that would one day swallow up San Francisco — and L.A., too, if it kept dissing him.

The townspeople indulged and needled him. When he bragged that he could raise the dead, some pueblo jackanapes stuffed him in a box, lowered it into the ground and began shoveling earth upon it until Bishop Doctor Professor Money hollered, “For the love of God, let me out!” His torrent of letters to the editor of the Los Angeles Star fulminating against anyone who didn’t believe in all things Moneyan got so tiresome that the paper finally stopped publishing anything he wrote.

He ended his days in 1881 in San Gabriel, at the Moneyan Institute, an oval house with a bed of tenderly cultivated tulips in front and, beyond that, a pair of large, octagonal wood-and-adobe gateposts, the gates inscribed with Latin, Hebrew and Greek phrases. Some of his faithful had maintained the Money Society as a social and benevolent organization. For all of his epic anti-Catholic rants, Money’s deathbed had the figure of the Virgin Mary at its head and a skeleton carved into its footboard. The black granite gravestone in San Gabriel Cemetery describes him as “physician theologian philosopher writer naturalist historian.” He probably would have found that inadequate.

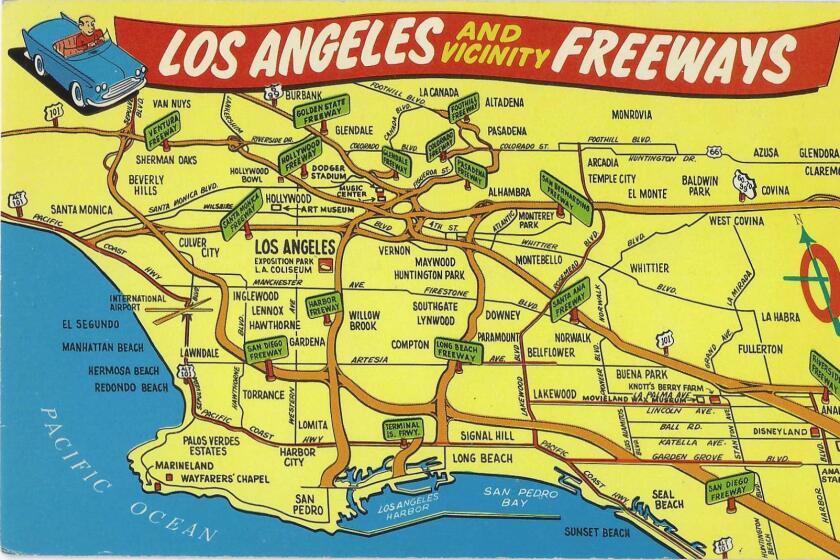

There is no Beverly Hills Freeway. Nor does the 2 connect to the 101. What even is the 90? These are the freeways that didn’t happen as planned.

There was no stopping L.A. after that. People who uproot themselves and look here for the church or faith they’d left behind, or decide to break from it completely, have no trouble finding something among the endless sects that seem tailor-made for their restive new L.A. lives and new outlooks: New Age and old-time religions; ministers and priests; gurus and prophets; God-spieling grifters; spiritualists and spellbinders, sacred and profane.

As The Times wrote years ago, “No other community on the face of the globe has given rise to half as many mystic, philosophical, psychological, occult, consciousness-raising, therapeutic and alternative creeds as 20th century L.A.”

New sects could repackage and market themselves out of ingredients from older ones, like tweaking a recipe: a pinch of that Eastern religion, a sprinkling of this psychology (or pop psychology), an immodest dash of the divine, a soupçon of the occult, a helping of Christianity and ... bon appetit.

It bears pointing out that for all the crackpot credos that flourished here, Los Angeles also opened millions of minds to earnest spiritual questing, the sagacities of Eastern religions and philosophies and vegetarianism and healthy living.

As for the ones that went off the rails, I’ll have to limit myself to just a sampling, or we’ll both be here all day.

Mount Helios

In 1912, Edith Maida Lessing wrote the lyrics to a lachrymose ballad about the sinking of the Titanic. Nine years later, she had bobbed her hair — and let it down. Police busted her in the Glassell Park compound she named Mount Helios, for the Greek god of the sun, atop which she flew a red flag lettered with “Love.”

The newspapers luridly called her a “priestess of a strange love cult” who supposedly bragged that she controlled a thousand men. The anarchist squad — the LAPD had such a thing — turned up placards printed with the word “Revolution” and exhorting readers to become libertines.

Lessing argued for free love, the end of civil marriage, free child care, profit-sharing, free public transportation for working people and free trade.

She invited a federal rap upon herself by mailing to The Times and the postal inspector yellow-printed pamphlets described as “lewd and lascivious.” This wasn’t porn in the sense that we know it but likely information about birth control, as well as what reporters called her “radical” political views. With World War I ending and women about to get the vote, women had been demanding such information, but it was illegal. In 1916, Margaret Sanger, founder of Planned Parenthood, was arrested for giving women contraception information, and Marie Stopes’ discreet 1918 sex manual “Married Love” was radically helpful for women brought up in ignorance about their own sex.

Lessing was sentenced to time in a “female reformatory” in Missouri, where she occupied herself teaching her insights to incarcerated ladies of the evening.

Generals and outlaws, heroes and villains: L.A.’s parks are named for a colorful cast of characters.

Mazdaznan

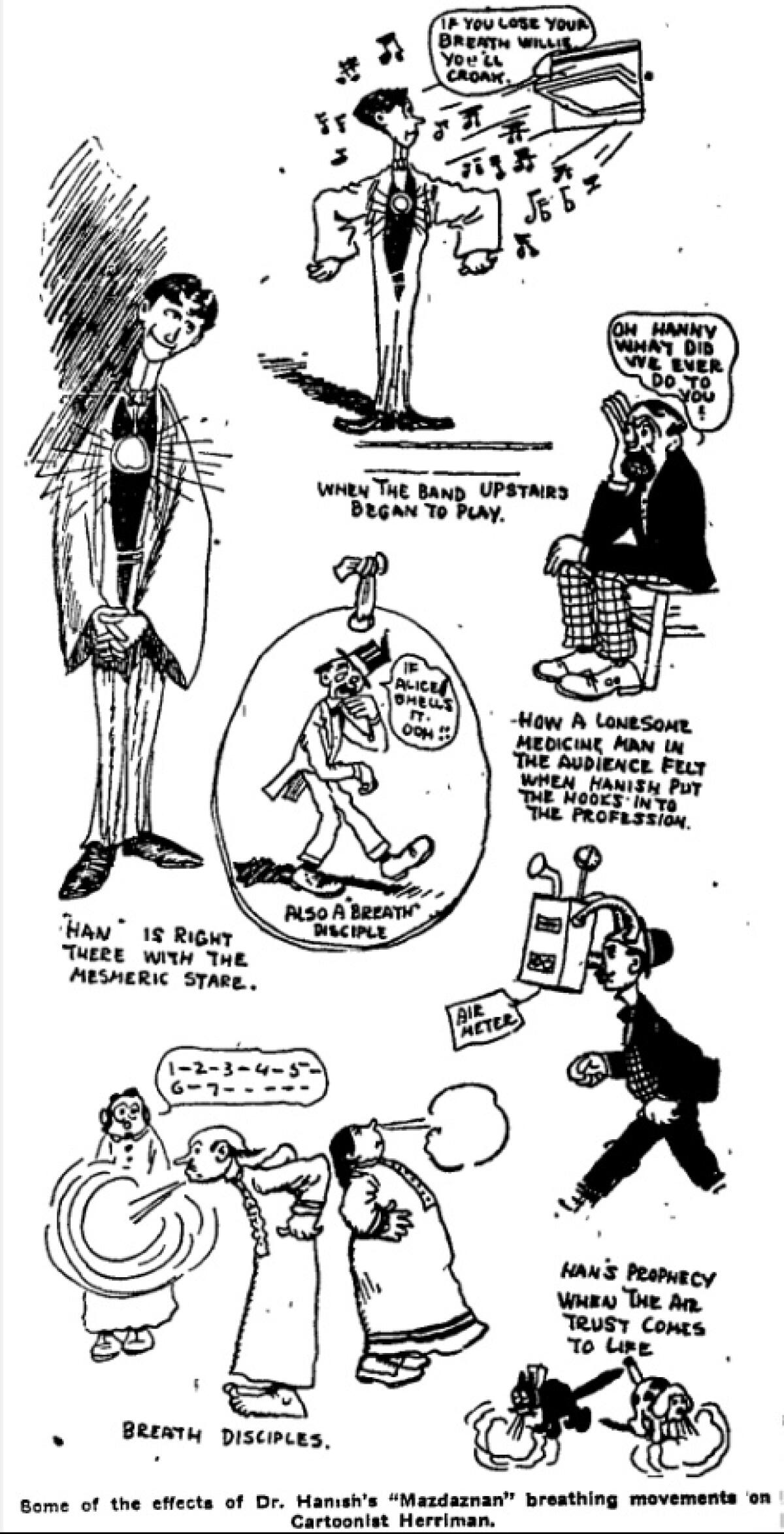

In 1906, Ernst Otto Haenisch, calling himself Otoman Zar-Adusht Hanish, visited here from Chicago to lecture about his sun worship faith, Mazdaznan. He spoke to a Times reporter in the royal “we” and explained the virtues of fasting.

A snippet from his literature: “Mazdaznan denies not the existence of matter and its consequent process through the four dimensions of space, but holds the latter to be dependent upon our mental perception, recognizing in the variation of manifestation a complex whole.” (There will be a test.)

Breathing exercises and vegetarianism were among Mazdaznan’s more sensible practices.

Hanish’s legal troubles began when relatives inquired about the welfare of a boy who was being fed white grapes and beer, and whose mother was a rich widow and Mazdaznan follower.

Mazdaznan’s criminal and civil cases kept L.A. courtrooms busy from the end of World War I to the eve of World War II, when a 19-year-old sued the sect and a member for $1 million, saying she had been sexually attacked at a meeting when she was 11. (She lost.)

Ten years before that, a former imperial German army officer sued Hanish for luring his wife away from him. And about 10 years before that, a judge acquitted Hanish of molesting a 14-year-old girl. Hanish was also accused of “criminal offenses” against other children and of practicing medicine without a license.

The newspapers relished details of men, women and children performing breathing rituals in their skivvies in “morning dew baths” on the lawn. Hanish’s temple was a Greek Revival building that still stands in Arlington Heights.

General Motors? Big Oil? Big Rubber? The demise of L.A.’s streetcars stemmed from public policy and our own appetite for automobiles.

Blackburn cult

Short of the Manson gang, the Blackburn cult may rank as L.A.’s creepiest.

The Divine Order of the Royal Arms of the Great Eleven, inspired by a passage in the Book of Revelation, invested prophetic power in a mother and daughter who did not scruple to use sex, gullibility and greed.

May Otis Blackburn was a 60-year-old clairvoyant when the archangels Michael and Gabriel appeared to her and her daughter Ruth, the “girl of many loves,” as the press delighted in calling her. The women were divinely ordered to write a book called the “Great Sixth Seal,” supported in this work by Ruth enticing loans from her beaux. More crassly, the archangels promised to give the women the “lost measurements” to finding oil and gold deposits across the world. That was enough for the nephew of a local oil magnate to join the cult and fork over $40,000 in cash and 164 acres in Simi Valley, in exchange for those “lost measurements.”

The mother-daughter team set up their compound there, making pronouncements from a gilded throne and snapping up the paychecks of their acolytes’ work in a tomato-packing plant. Some nights, the two purple-gowned women — why is it always purple with such people? — would summon their followers to a hillside to witness the ritual slaughter of mules, which the women called “the jaws of death.”

A rich couple and their daughter Willa joined the cult. When Willa died from a tooth infection on New Year’s Day 1925, the prophets packed her in a bathtub of ice garnished with salt and spices. Willa was a priestess, they told her parents, and would return to life in 1,260 days.

Her parents buried her metal-lined coffin under the floorboards of their Venice home. Four years passed. Willa was still dead. The oilman’s nephew sued for fraud. Former believers went to court with their own claims. The cops came looking for missing cult members, and in 1930, even though Gabriel assured Blackburn she’d be acquitted, she was convicted of grand theft.

But California’s Supreme Court found that Blackburn was wrongly convicted.

“It is not actionable to the court if the defendant made certain representations as to being divine.”

A world that has long embraced love, light and acceptance is now making room for something else: QAnon.

The Great I AM

The Great I AM began when its founder, Guy Ballard, was hiking on Mt. Shasta and met St. Germain, a fellow in a jeweled robe, an “Ascended Master of the Great White Brotherhood.” He gave Ballard a cup of “pure electronic essence” and carried him airborne to see the treasure cities of the world.

Ballard accumulated more than a million followers who answered his alarming mass mailings about the end of the world and about what comfort could be found in joining I AM and consigning their bank accounts to its leaders’ care. “Love gifts” and the sale of such I AM-branded products as rings, engravings and “New Age cold cream” made millions.

Ballard’s radio broadcasts preached a prosperity credo, and his channeled “thoughts” of St. Germain and Jesus are sold on Amazon to this day. They were also the subject of a copyright lawsuit by the authors of “A Dweller on Two Planets.”

In 1940, a year after Ballard died, his widow and son were tried for mail fraud over their $3-million “take.” The defense proclaimed that the nation’s safety depended on Ballard’s divine power and that before he died, he had invoked an invisible force to sink a flotilla of Japanese submarines no one had ever seen. This jury couldn’t reach a verdict, but a later trial convicted the widow Ballard and her son. The Supreme Court tossed it out. The jury, it ruled, shouldn’t have been allowed to decide whether the defendants actually believed what they were saying.

Justice Robert Jackson, soon to be chief prosecutor at the Nuremberg Nazi war crimes trials, wrote that there is “wide variety in American religious taste. The Ballards are not alone in catering to it with a pretty dubious product … [but] I would dismiss the indictment and have done with this business of judicially examining other people’s faiths.”

The judge in the first trial agreed to wear a light-colored business suit rather than a black robe because the defendants “honestly believe that light and bright colors have a favorable effect on their soul’s welfare … if the situation warranted it, I could function as well in a bathing suit.”

The St. Germain figure also makes an appearance in the credos of Elizabeth Clare Prophet, the “Guru Ma” of the Church Universal and Triumphant movement, which moved from Pasadena to the Santa Monica Mountains and then, in 1981, decamped to Montana.

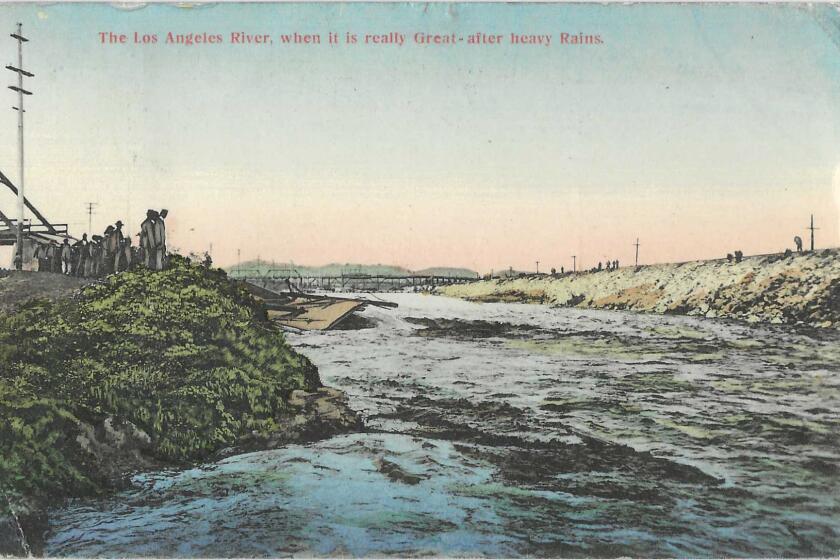

After one too many floods, L.A. turned its river into a concrete channel. Today and in the future, the river could be part of the answer to some of the city’s problems.

Thelema

Remember the decorously offended Victorian lady from Pasadena? How she would have recoiled to know that devotees of the faith called Thelema lived after World War II among the grand mansions of Pasadena’s Millionaire’s Row.

Thelema originated with the British occultist, magician and writer Aleister Crowley, who said its precepts were dictated to him by the voice of a being named Alwass. Crowley blended Thelema and an older creed called OTO, Ordo Templi Orientis.

The head of the local branch of Thelema was Jack Parsons, a brilliant rocket scientist whose work was foundational to the Jet Propulsion Laboratory and modern rocketry. It was at his place on Millionaire’s Row that members sometimes met and lived.

The late Times reporter Nieson Himmel told me he lived in Parsons’ house for a while, as did an acquaintance, the writer L. Ron Hubbard, who would go on to found the Church of Scientology. Himmel said that Parsons “believed all these weird things, and all this science too. … A couple of times I came downstairs [and saw] people wearing black robes.” He also talked to an old Englishman living in the carriage house, who “gave me all this about the role of evil — he was very happy about it.” It was, as Himmel described it, a kind of fluid, free-love/occult/scientific communal-living setup.

Then, in June 1952, Parsons, a world-acknowledged expert in explosives, was blown to pieces outside the carriage house. He evidently dropped fulminate of mercury that he was loading into his car, and boom.

The theories of what went on in that house, and about Parsons’ end, have engrossed writers and filmmakers for decades. Accident? Suicide? Murder?

Years ago, I interviewed a couple of Pasadena policemen about what they saw. Ernie Hovard got to the scene not long after the explosion. He knew the house, he told me, because his mother had once worked as a maid there.

“I remember thinking [Parsons] was messing around with two chemicals that didn’t blend together and blew his hands off.”

Officer Bob Orman spent three days at the crime scene. He was stunned to see the mansion, with “outlines, silhouettes of big, giant bats painted on the walls in black, with candlestick holders where the tips of the wings would be” and nude photos in the bedrooms of one of the women living there. Orman told me he remembered coming across Parsons’ severed foot. The combat Marine who survived the Inchon landing recognized the shoe as a Marine Corps “boondocker” boot.

For much of its history, Los Angeles didn’t have a city flag. It does now, and it stands out for its sawtooth bands of bright color, one of which is supposed to represent orange crops.

Synanon

When CBS News’ equable anchor Walter Cronkite uses the phrase “bizarre cult” and your name in the same sentence, you’ve lost the plot.

Synanon, originally a drug-and-booze rehab program, began in 1958 in a rundown Ocean Park storefront. A recovering boozer named Charles Dederich used his $33-a-week relief check to start a rigorous residential program that pretty soon was getting praise because its confrontational group-therapy technique, called “the Game,” seemed to work.

Dederich taught a Berkeley extension course about it. Synanon went national and soon welcomed people who weren’t addicts.

But then, as the story arc goes, things got dark. Women members were ordered to shave their heads. Married members were told to divorce and find new partners. The way some former insiders described it, Synanon was a kind of Hotel California — you could check out, but you could never leave.

Critics and investigative journalists found themselves harassed and threatened. Synanon began styling itself the Church of Synanon.

And then came the rattlesnake-in-the-mailbox incident.

In 1978, an L.A. attorney who’d bested Synanon in child custody cases was bitten by a large, derattled rattlesnake someone had hidden inside his mailbox. He spent six days in the hospital.

Investigators found tapes of Dederich calling down violence on his foes’ heads: “Our new religious posture is this: Don’t mess with us. You can get killed dead. Physically dead.” If the public hadn’t paid close attention before, it did now.

Eventually, Dederich and two of Synanon’s “imperial marines” pleaded no contest to the attempted killing. Dederich had to forfeit control of Synanon. The Justice Department called out Synanon as a front to enrich its leaders to the tune of millions. The IRS yanked the group’s nonprofit status, and in 1991, burdened by tax debt, Synanon went belly-up. Dederich died six years later.

A gutsy little Marin County weekly paper, the Point Reyes Light, won the Pulitzer Prize Gold Medal for its exposés on Synanon.

Yet over nearly 200 years of occasionally unhinged kookiness, we have not fulfilled the hideous terror invoked by Woody Allen’s character in “Annie Hall,” dragged out of New York for a Los Angeles scene and hyperventilating over the city’s “ritual, religious cult murders! There’s wheat-germ killers out here!”

Los Angeles is a big, complicated place. Patt Morrison explaining how it works, its history and its culture in Explaining L.A. on latimes.com.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.