Why we turned the L.A. River into a freeway (for water)

If the Los Angeles River had its own IMDb listing — and why shouldn’t it? It’s appeared in all kinds of movies — its career arc would look something like this:

- Leading man for tens of thousands of years, star and creator of the epic story of Los Angeles’ ecosystem and living things.

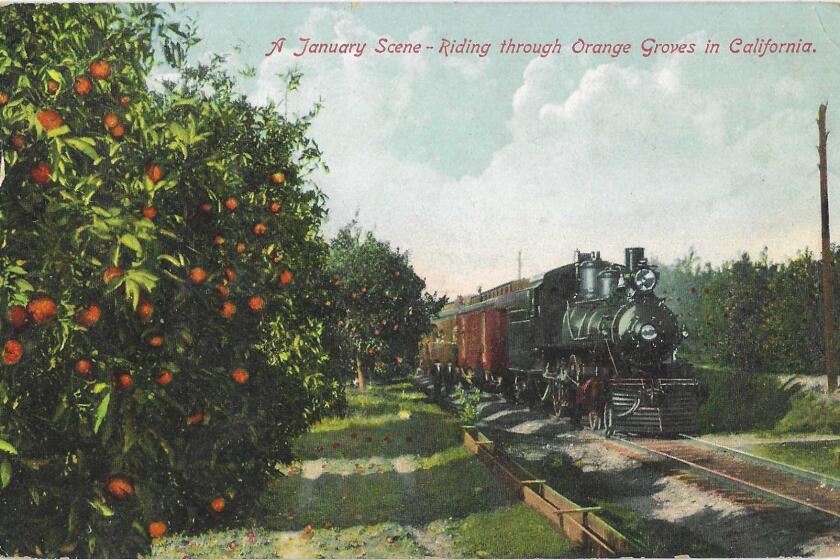

- Demoted to a supporting role around 1913, when L.A.’s new producers and directors began importing younger, more reliable water.

- Thereafter cast occasionally as a serial killer for performances as deadly floods.

- Blacklisted from river roles and “disappeared” under concrete since the Depression.

And now, also in Hollywood fashion, after decades as a nonentity, the L.A. River is having a career revival, starring as itself in an urgent real-time, real-life comeback docudrama.

End of movie metaphors, if for no other reason than L.A. may not be able to write for the river the happy ending everyone wants but no one can agree on.

And yet, fellow Angelenos, that is progress.

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

Twenty, 30 years ago, scads of you didn’t even know there was a Los Angeles River. When people asked where I lived, and I said, “east of the river,” they waited for the joke. My old pal, the actor Harry Dean Stanton, phoned up one day and asked what I was up to. Writing about the L.A. River, I said. And Harry, a man not given to expressing astonishment, said, L.A. has a river? Harry! I told him — you made a movie in it — “Repo Man.” Oh, right, he said.

So that was the river then — demoted to a flood control channel, wet most of the year thanks only to a grudging trickle out of water reclamation plants and getting only a trickle of interest from official Los Angeles.

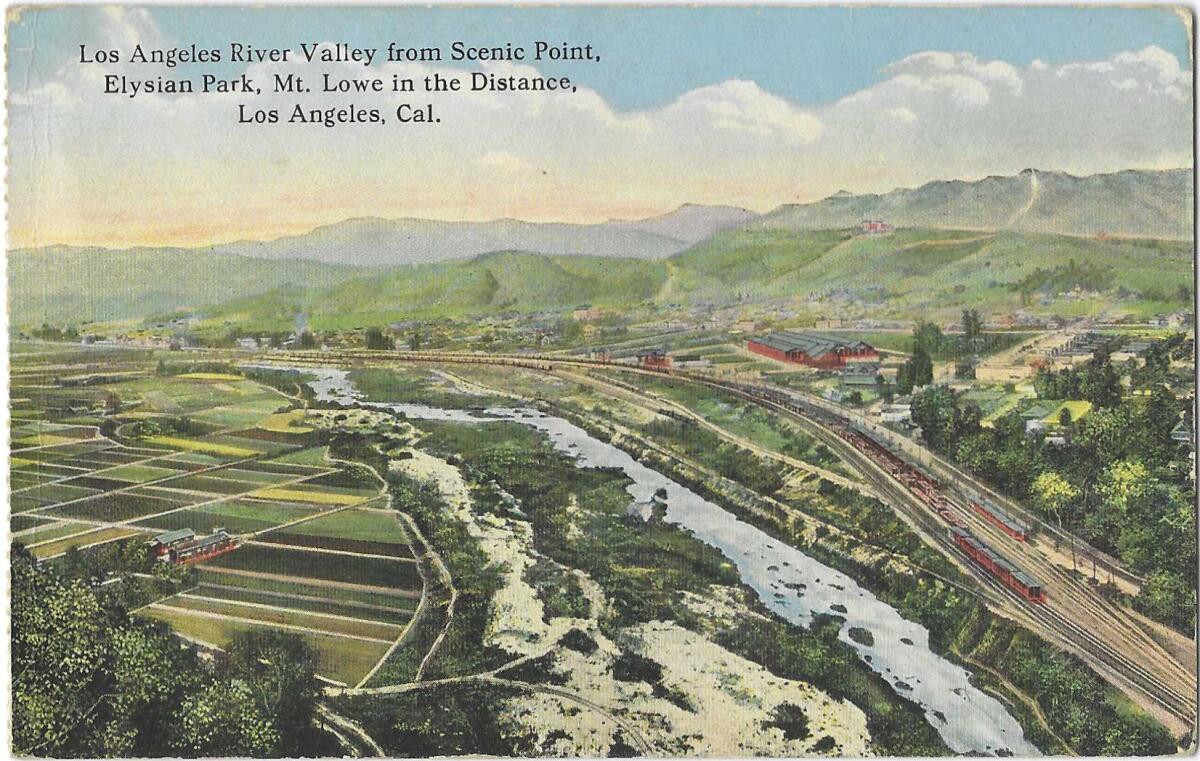

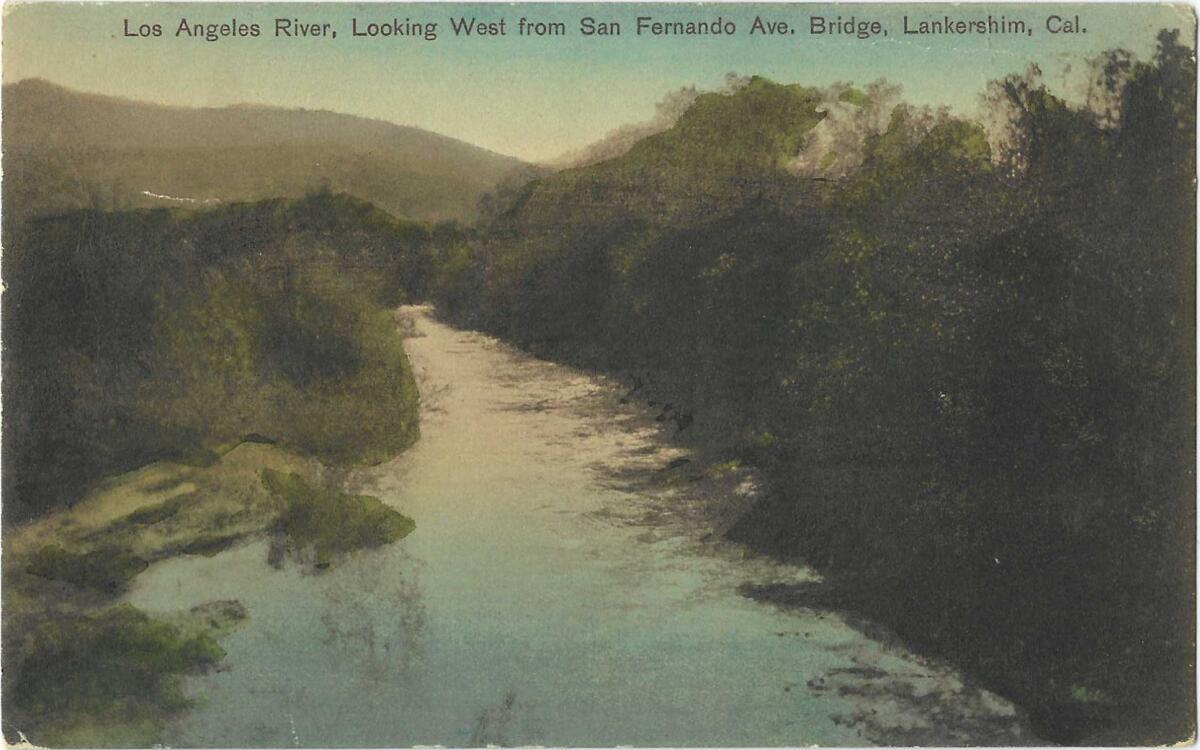

But people started to look at it and to ask questions. A poet named Lewis MacAdams imagined the ancient, real river trapped inside the built imprisoned one, and asked Angelenos to do the same. The county’s 17 riverfront cities — some of them existing only because concrete walls protected them from floods — were choked with people and buildings, and in the 51 miles of wide, mostly desolate and desiccated riverbed, there lay, tauntingly, more space than in New York’s Central Park.

So the river became a hot property. Environmentalists, artists, community and civic groups each had reason to reclaim the river, for bicyclists and fly fishers — it now has both — for riverbed greenery, for fish and frogs and waterfowl, and just the novelty of open space.

Twenty-first century money and civic muscle have turned riverine land near Chinatown into a park, and have begun converting toxin-soaked railroad river corridors into open lands.

That, as it turns out, may have been the easy part. Now that there is a wind at the back of reclaiming the river, now that there may be ribbons for politicians to cut with giant scissors and names to be credited on dedicatory plaques — now that everyone wants a piece of the orphaned river, there aren’t enough pieces to go around, to satisfy every interest and demand: environmental, natural, recreational, residential, drought-minded.

How did we come to this? From an actual, living river, how did we get here?

Like great cities of the world — London, Cairo, Paris — without its L.A. River, there wouldn’t be a Los Angeles.

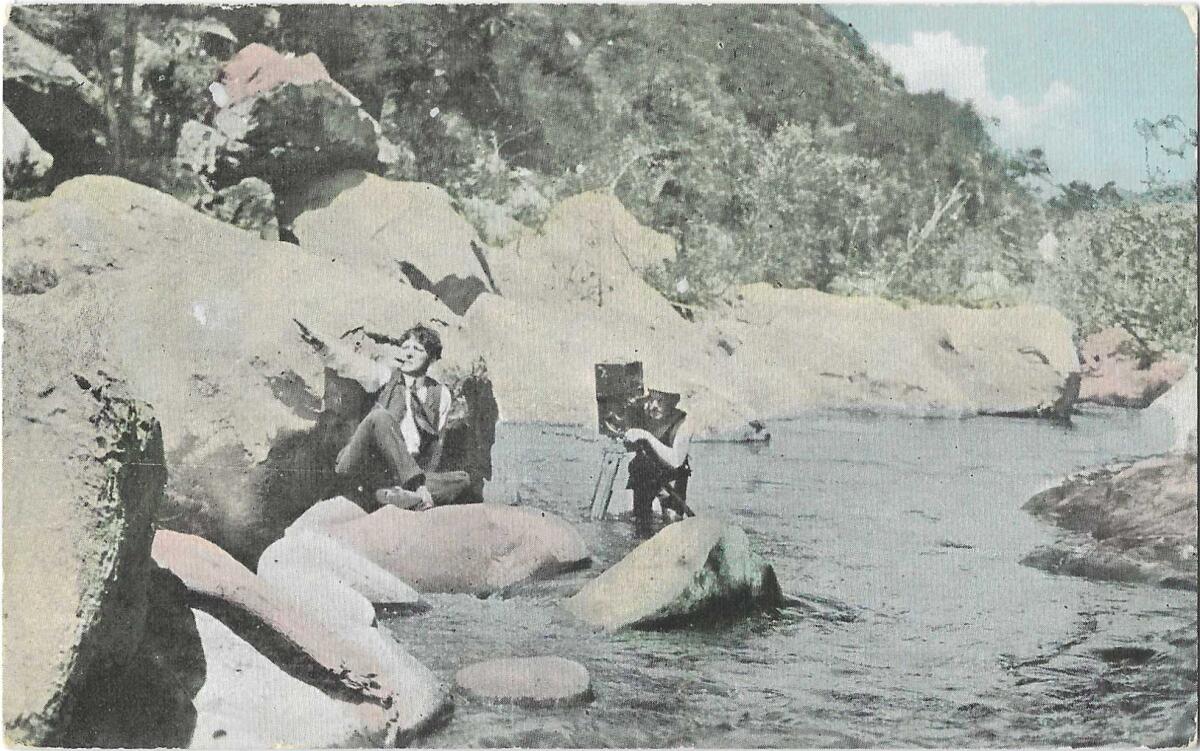

But ours was never that kind of river, flowing rich and full year-round for ships and fish and riverfront amusements. It was a Western river, brawny and unpredictable in the winter with runoff from a watershed bigger than the island of Maui, and sparse in summer, running in a braided lacework of streams and springs off the hillsides and across the plain of Los Angeles.

Our river didn’t send a roaring torrent into the Pacific, but spread itself into a thousand little paths and wetlands and arroyos. Until a flood of 1825 changed its course, the river flowed from the San Fernando Valley into the Elysian Valley, and turned west from near where Exposition Park stands.

Because of it, thick scrub oak forests grew where the Santa Monica Freeway runs. If you were to excavate beneath the seven-figure houses of the Westside, you might find enough peat to craft a decent Scotch. After 1825, the river coursed south instead, and within a generation, the plain’s thousand-year ecosystem began to disappear.

The Tongva, who lived here for a hundred centuries, paced their lives to the river’s and named its seasons “it is full of water” and “the water has departed.”

Only in the last 250 years, with the arrival of Spaniards and Mexicans and Yankees, did the river that sustained flora and fauna and human needs get recast as a failure — how Goldilocks might find a river: too little water, and too much, almost never just right.

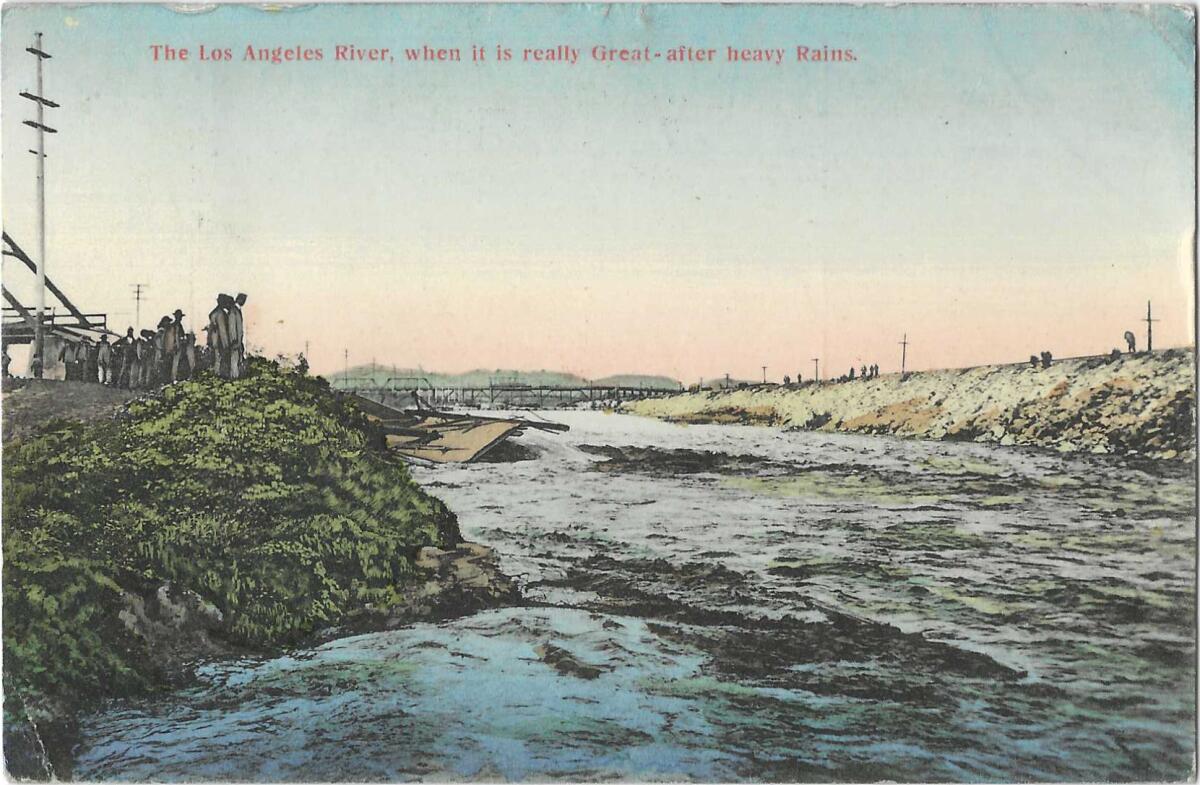

Some of our history can be told through our earthquakes, and some can be told through the river’s floods. No one knows where the city’s original 1781 pueblo stood because the river floods swirled it away, and probably the next pueblo the settlers built, and even the one after that.

After a month of rain, the flood of 1861 submerged L.A.’s agriculture, drowned thousands of cattle — the principal economy — and two months later, another flood joined the L.A., San Gabriel and Santa Ana rivers into a vast inland lake. For a waterway that L.A.’s new masters didn’t think amounted to much, the L.A. River dictated our fortunes.

A capricious, seasonal river was not what L.A.’s new Yankee masters wanted or needed. From the mid-19th century, they dammed and leveed and regulated the river to move the water around the way we do now. For a time, a waterwheel below the Chinatown cliff scooped water from the river and into a flume toward old downtown, where among other services it powered the L.A. Times’ early printing presses. Occasionally, a steelhead trout got flung down the flume and squished in the printing works.

Barely two months after the paper’s owner and publisher, the L.A. empire-builder Harrison Gray Otis, had taken over the paper, he ran this florid apologia for the meager, capricious river:

“Our river is unlike the ‘father of waters’ [Mississippi River], in that it is not the father of many waters, and the argosies of Commerce do not ruffle its bosom ... nor bear our wealth to other climes in its march to the ocean. Yet still it is a river, and we are able to show that it is a right useful one, even if too insignificant to be a burden-bearer, or to turn the whirring wheels and spindles of but few manufactories. It should be acknowledged that it’s the life of the emporium of Southern California, and we should do it a deserved homage.”

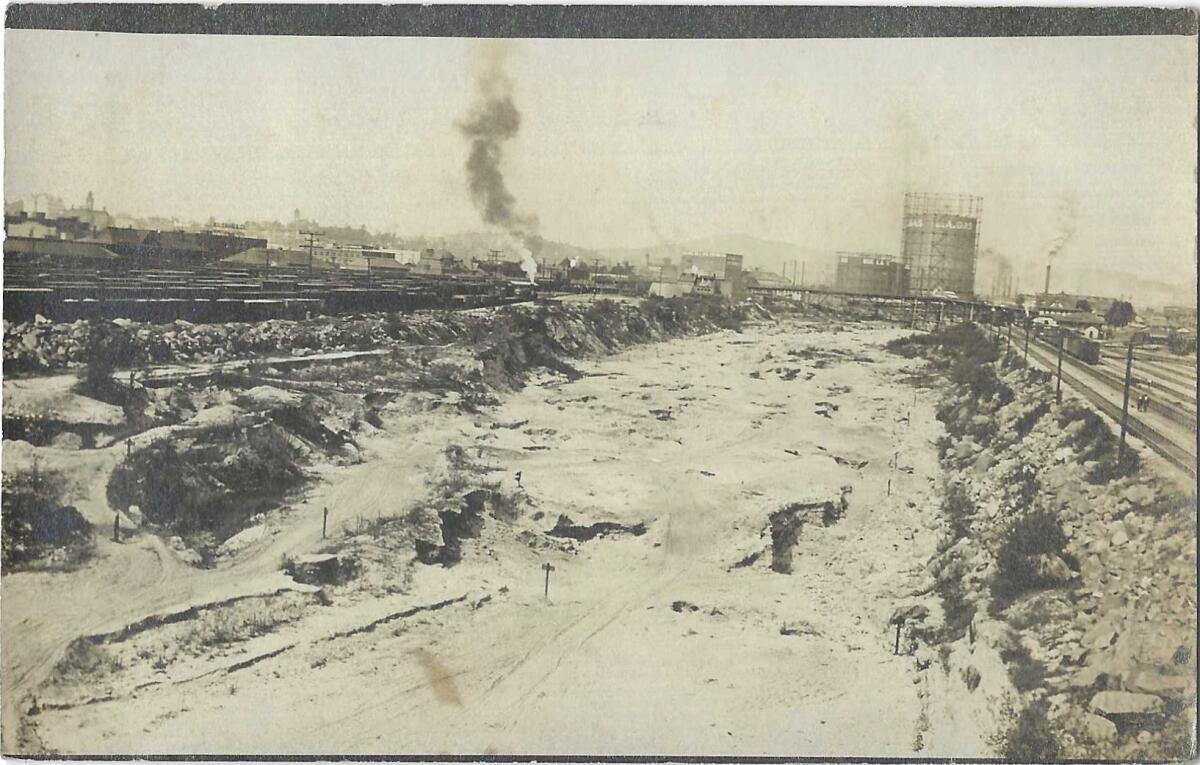

The river was too untrustworthy to be a showplace for rich men’s homes. Instead, it became a trash chute. A bleach factory, a slaughterhouse, an orphanage and other undesirable institutions rose along its banks. The railroads bought up its unsavory flanks, and for a time the city fathers were so embarrassed that the thousands of newcomers arriving by train first saw this paltry river that they proposed — not to tidy it up, but to plant hundreds of trees along its banks to block the view from train-car windows.

The rail yard thefts and resulting garbage have made a scene in L.A. But the train robberies of California’s past were decidedly more violent.

Those thousands and then hundreds of thousands of new Angelenos also doomed the river. The river’s rich underground aquifers had quenched L.A. but weren’t enough for new people and new thirsts.

New people needed new houses, and too much real estate was lost — wasted, they said — by the river’s seasonal wanderings; a house that looked high and dry one year could be sent halfway out to sea the next year. Something, as the phrase goes, had to be done.

The 1914 flood that destroyed a vast pigeon farm along the banks of the river near Elysian Park prompted the county to create a flood control district of dams and channels. Official L.A. was already congratulating itself that the year before, it had opened the vast L.A. Aqueduct, bringing orderly, well-behaved, 24-hour-a-day water to L.A. from the Owens Valley. The river was looking not just unruly, but obsolete.

Wildfires in November 1933 were followed by a foot of rain the next month, and early on New Year’s Day in 1934, tons of mud and debris rampaged down from the slopes of La Crescenta, Montrose and La Cañada. At least 60 people died, and probably many more went uncounted, among them migrant workers. Dust Bowl troubadour Woody Guthrie, working here at a radio station then, wrote a song to commemorate it: “Oh, my friends, do you remember? On that fatal New Year’s night/The lights of old Los Angeles/Were a-flick’ring, Oh, so bright./A cloudburst hit our city/And it swept away our homes/It swept away our loved ones/In that fatal New Year’s flood.”

If you had set out to design a flood-making machine, you might have ended up with L.A.. Like the Mississippi River, the flow of the L.A .River and its tributaries drops about 800 feet from source to mouth. But the Mississippi River descends that 800 feet over 2,000 miles; the L.A. River does it over barely 50 miles.

The river flooded yet again in 1938, tearing out bridges and trestles. It killed more than 100 people, trapped movie stars on their San Fernando Valley ranches, and forced a three-day delay in the Oscars. The water tore away the Warner Brothers studio’s prop department, and for the span of a few moments, a huge prop whale swam majestically down the Los Angeles River.

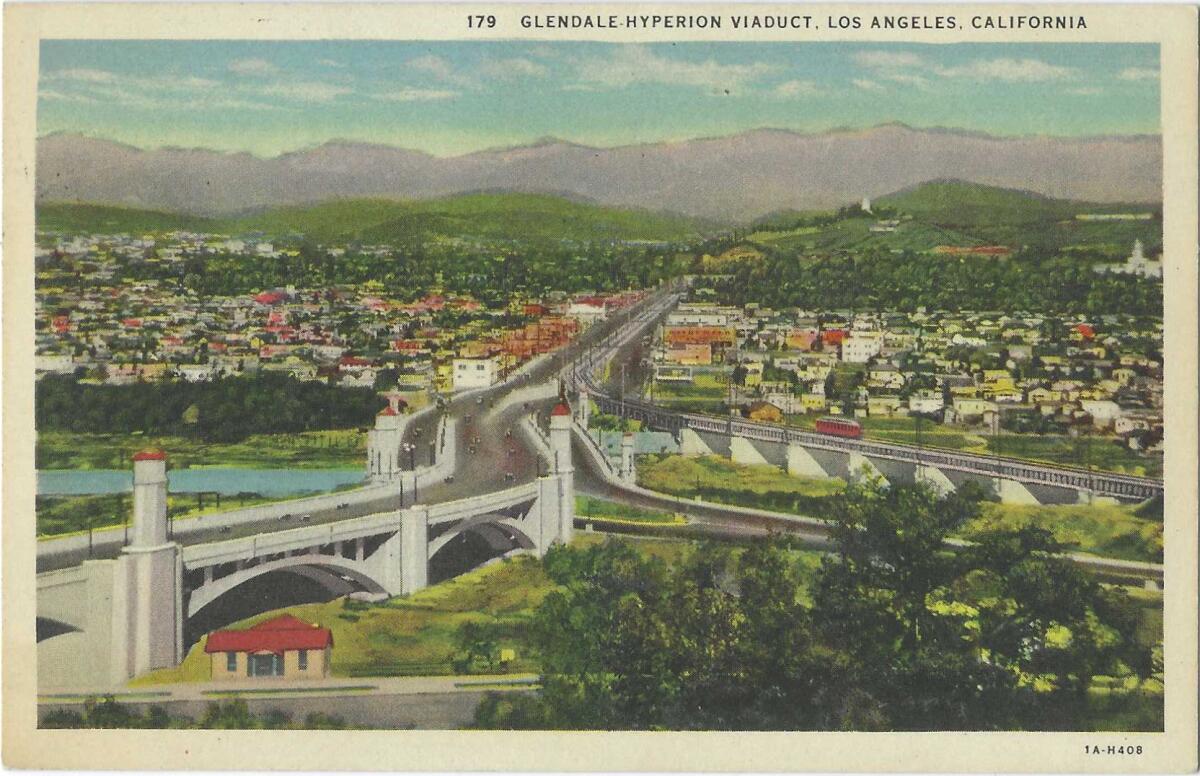

That flood wrote the real river’s death warrant. It was the Depression; L.A. needed jobs, not a willful killer river. The river was timbered and troughed and cemented over, mile after mile. Only in parts of its 51-mile bed would it assert itself and remain persistently unpaveable: for about three miles around Atwater Village, and along more than two miles at the broad reach of the Sepulveda dam wildlife area.

During World War II, trucks sped loads of munitions and war material down the paved river to the harbor. After the war, frustrated drivers found their way to drive up and down the length of the “poor man’s freeway.” One legislator did propose just laying down medians and making it a freeway. The Long Beach Freeway’s original name was the Los Angeles River Freeway but maybe it felt a little too much like wearing a “kick me” sign.

The funny thing is that the river’s existence disappeared from the city’s imagination and memory as fast as it got wiped from the landscape. A city that could imagine its own improbable existence into reality could just as easily relegate this now-inconvenient natural feature into a nullity or a comedian’s gag.

The road signs above its vastness identified it as a dead, manmade thing — a flood control channel. Not until decades later, in an epic guerrilla civic prank, did future council member Tom LaBonge and poet MacAdams persuade the city sign shop boys to make official signs reading “Los Angeles River,” and to get them installed on the QT.

Moviemakers didn’t forget, as I said at the outset. The bland, bleak stretches of concrete seemed purpose-built sets for motorcycles and racecars and helicopters, in action movies like “Terminator 2” and the hotrod sequence in “Grease,” music videos, and in my favorite L.A. River movie, “Them!” — gigantic mutant ants invading L.A. via the river.

Twenty years ago, I wrote the book “Rio L.A.: Tales From the Los Angeles River,” about the once and future waterway. Now the future is practically upon us. For the 2028 Olympics, surely we should expect to have something to show the visitors — maybe a beta version of a river project, like a little lagoon near the new Sixth Street bridge tricked out with paddle boats and a riverside café.

A 20th anniversary edition of my book has just been published. In it, I note two decades of development, like ambitious river master plans, like architect Frank Gehry’s ideas for “platform parks” above the river in crowded downriver cities that were farmland before the war, cities where high river walls now mean safety, and a new spirit of public engagement and argument over the concrete canvas that could let L.A. craft its image of its new and future self, a greener city, an environmentally and socially just city.

It need not be — probably can’t be — a single vision for the river. Thirty-one miles of the river lie in the city of L.A., the other 19 inside the limits of 16 other cities, and each of those may need and want something different from its allotment of river.

Yet at last we are realizing the folly of throttling even a capricious river into a water freeway whose sole purpose is to flush away to the ocean as much winter floodwater as possible as fast as possible — at the same time we are desperate to find enough water to sustain ourselves.

We’re also realizing that we exist not apart from the environment but in synch with it, that we can’t starve the natural world of water — as we did by walling off the river — without starving ourselves. Already cities have begun fighting to keep for their faucets the meager year-round runoff from water reclamation plants that keeps the living part of the river alive.

Moviemakers, painters and authors have long opined on the quality of L.A.’s light. A Caltech scientist illuminates on why our light is so remarkable.

If we can’t get it exactly right, at least this moment is a rare second chance at getting it better.

The first chance at redemption slipped through our hands more than 90 years ago. In 1927 the Chamber of Commerce, as powerful as any branch of civic government, had an assignment for two landscape architecture firms. One of them was run by the sons of the man who designed Central Park, Frederick Law Olmsted.

Already, L.A. was far-flung, and possessed of too few parks. Its natural beauties were vanishing. So in the report “Parks, Playgrounds and Beaches for the Los Angeles Region,” the designers crafted their famous “emerald necklace” of parklands and riverside seasonal overflow open spaces, all encircling and enriching the city. They even suggested the means to pay for them.

As Greg Hise and William Deverell laid out in their 2000 book “Eden by Design,” this exquisite, wise and farsighted plan — which would have given us a Los Angeles so livably different from the one we live in today — was bigger and more visionary than the Chamber had expected. Adopting it would be expensive, and would shift something in the power axis of L.A. “The Chamber feared that the child had become the parent.” And so it was not merely ignored — it was hidden away. To read its might-have-beens all these decades later will make you cry for the loss of it.

We can’t reverse-engineer the river; we can’t make water flow upstream. We can’t make all the concrete disappear, without putting some communities alongside it at risk of disappearing too.

But one day, some civic notable will stand on a concrete riverbank with a gold-painted pickaxe, and take a mighty and symbolic swing at L.A.’s environmental Berlin Wall. It’ll be the whack heard ‘round our world.

L.A. is a place like no other. You’ve got questions. Patt Morrison probably has answers and can definitely find out.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.