Behind the privacy hedges and block walls stand L.A.’s notable and notorious homes

Welcome home.

Not your home. Probably not a place you’d even want to be your home.

But welcome to some of the Houses of Los Angeles — notorious, historic and just plain fabulous.

Get the latest from Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. Luckily, there's someone who can provide context, history and culture.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

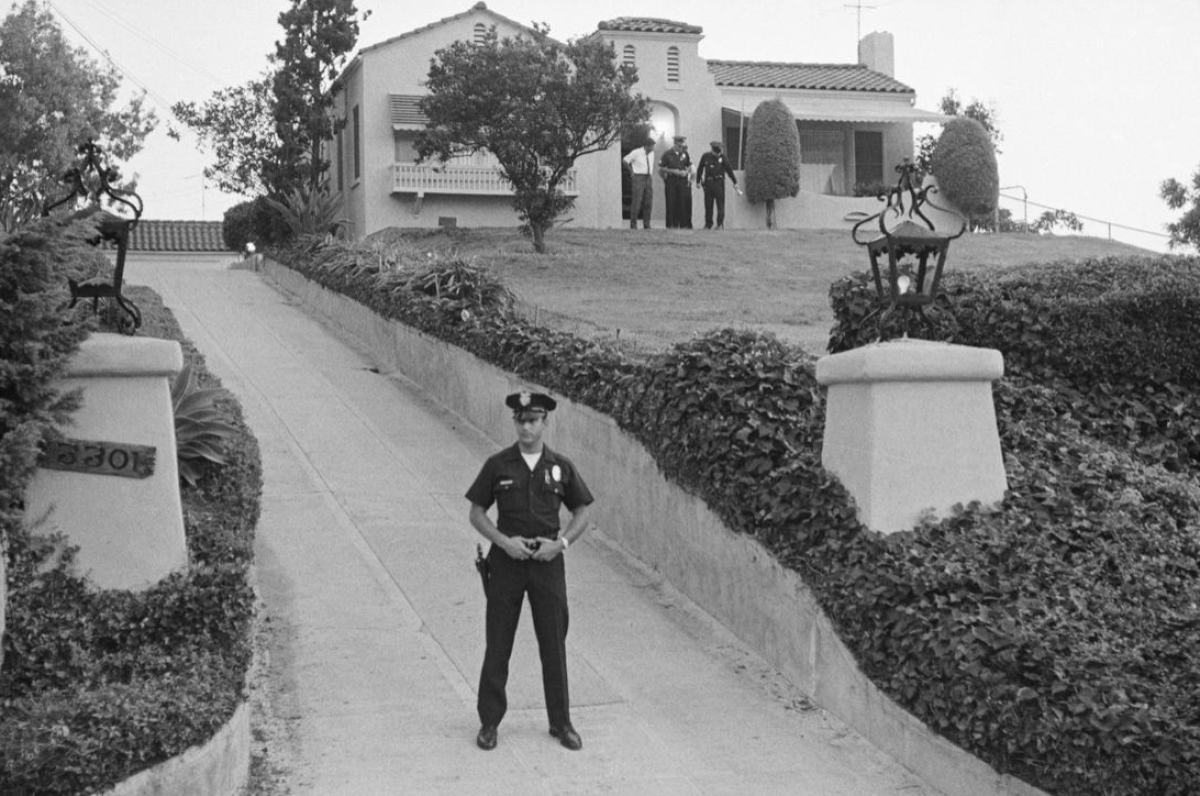

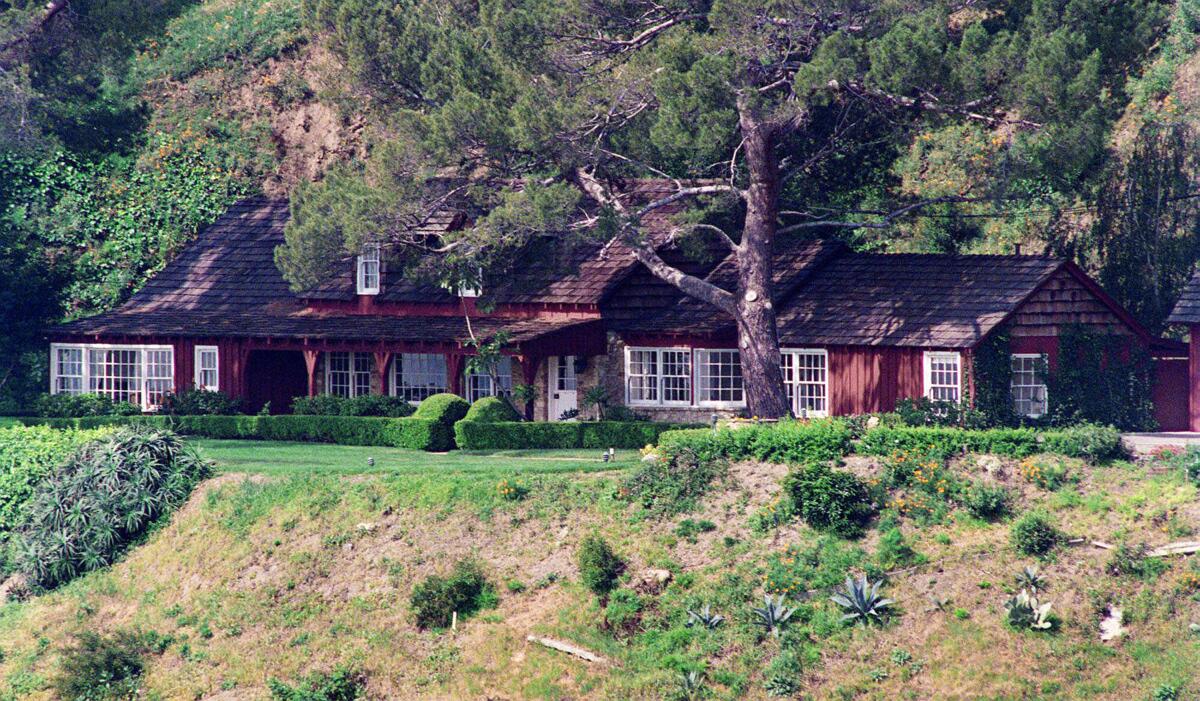

So many superb and significant houses have slipped through L.A.’s civic fingers and into the steel scoop of a bulldozer, yet the city has just chosen to make a stand in Brentwood, preserving in perpetuity as a cultural-historic monument an otherwise undistinguished 1929 Spanish-style house that actress Marilyn Monroe bought in 1962, lived in for six months, and died in.

It’s on 5th Helena Drive. There are 25 Helena Drives in Brentwood, each a cul-de-sac preceded by a different ordinal number — 7th, 19th, etc. It’s the handiwork of a 1920s developer, Richard Peter Shea, a poor man who made good and who also built Shea’s Castle, a grandiose Irish confection in the Lancaster desert. He may have named the cul-de-sacs for his daughter, Helena. In December 1932, two months after Shea’s wife, Jane, died, Shea’s body washed up in the surf near Venice. In his pocket was a glum note, and around his neck was a container holding Jane’s ashes. How’s that for a little excursion down the research rabbit hole?

You already know three kinds of L.A. houses: expensive, ridiculously expensive, and get-the-eff-outta-here expensive.

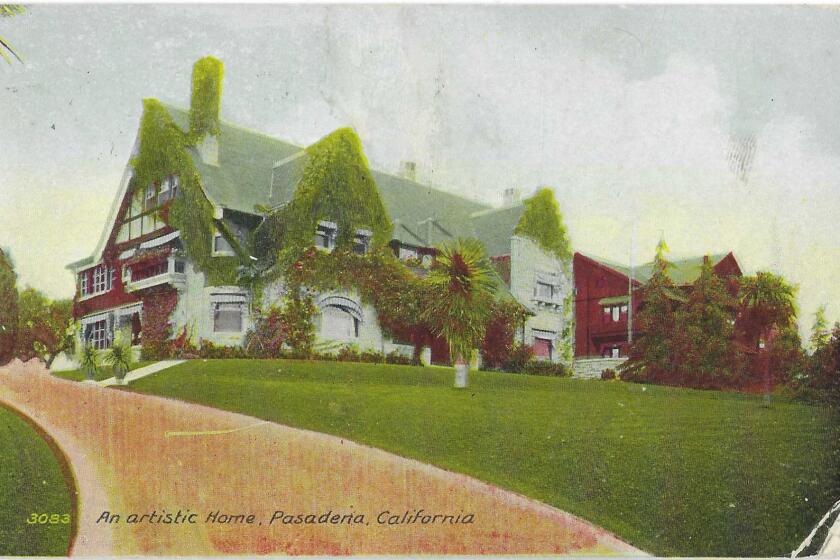

The L.A. area has long been home to ostentatious houses. Pasadena had Millionaire’s Row over 100 years ago. These days Bel-Air has “The One” and the “Starship Enterprise.”

So now, let’s have a lookie-loo tour of houses of another three kinds.

Here in Southern California, some of the greatest 20th century architectural talents devoted themselves to private residences. Richard Neutra, Paul Williams, Wallace Neff, Rudolph Schindler, John Lautner and his Chemosphere, Pierre Koening and his “case study houses,” made famous by Julius Shulman’s photographs, the Frank Gehry house that elevated plywood and chain link to artistry. Frank Lloyd Wright built eight houses hereabouts, one of them La Miniatura in Pasadena, which he said he “would have rather built … than St. Peter’s in Rome.”

Most are off-limits to public perusal. If only we adopted London-style blue plaques, at least people would know that places of note are in there somewhere.

The historic

Some adobes are survivors from the Spanish and Mexican eras, and they’re found from Calabasas to Whittier, San Fernando to Compton, Pomona to Long Beach.

A number are closed to the public. The 1852 Gilmore Adobe is one of them, not built by anyone named Gilmore, but named because it sits at the heart of the old Gilmore property that’s now the Farmers’ Market and the Grove.

The oldest non-Native-American house in L.A. County, the Las Tunas adobe, in San Gabriel, was built in 1776, the same time important people on the other side of the continent were doing some other stuff. It’s where the padres of the San Gabriel mission lived for a time, and it’s reputedly where the first orange seedlings in California were planted.

In the city of L.A. itself, the grand old man of adobes is the Avila Adobe, built in 1818 by Francisco Avila, once mayor of the city. More than a century later, it became the anchor to the makeover/restoration of Olvera Street.

To me, the most thrilling of them sits — sat — across from the thrill-ride capital of L.A., Universal Studios. On Jan.13, 1847, on the porch of this now-vanished adobe, two men signed a cease-fire agreement that ended the Mexican-American war in “Alta California,” Mexican California. The treaty’s terms were supposedly proposed by a Californio matriarch named Bernarda Ruiz de Rodriguez, who persuaded the two men to stand down. Andres Pico was a Californio statesmen and acting governor of Alta California, and Lt. Col. John C. Fremont was an American army officer always on the lookout for glory, whatever his orders.

The original adobe itself, 99 by 33 feet, was taken down in 1900 — it had been latterly used as a veterinarian’s office — and an approximate replica was built but, typically for L.A., neglected. In the 1990s, the MTA, about to build more turn lanes, uncovered the actual foundations of the original adobe, roof tiles, and ceramic floor tiles upon which the 1847 treaty-makers probably walked.

What to do? Make drivers wait another 90 seconds or so, or pave over one of L.A.’s most significant sites? At least part of it is preserved under glass at the Campo de Cahuenga historic site. Most drivers still turn into Universal City; the “Psycho” house means more to them than the Cahuenga adobe.

L.A.’s public beauty spots deserve a visit, by all means. But it’s the houses that surprise visitors and gratify us, even if they can only be glimpsed from a sidewalk.

I have a soft spot for the Banning House in Wilmington. Phineas Banning, “the father of the port,” was one of those go-getter Yankees who saw L.A. as a blank slate for the making and the taking. Like a Kansas house landing in Oz, Banning’s 1863 Greek Revival-style house stood out and stood apart in the land of adobes. It’s a miracle it survived to become the museum it is today.

Getty House is the mayor’s official residence in Windsor Square. For its day — 1921 — it was probably a stylish, gee-whiz place but today it’s a large, rather lumbering-looking mock Tudor house. It was given to the city in 1975 and is probably the most modest edifice to bear the Getty name. In the 1990s, mayor Richard Riordan raised private millions to spruce up the fusty place to make it fit for official receptions and events.

In 1997, one day after Riordan launched a crackdown on the 18th Street gang, taggers vandalized the place but ha ha, the joke was on them — Riordan didn’t live there. Neither did mayor Jim Hahn, nor for part of his term did Antonio Villaraigosa. Eric Garcetti did, as does Karen Bass now. She was there on an early April morning when a man broke in, and he now faces charges for it. Mayor Tom Bradley lived there with his wife, Ethel, who did wonders with the garden, but was not fond of the house itself.

In case it had crossed your mind, no, you can’t just drop in. Just ask the accused burglar.

The horrific

Crime sensations come and go — some lost in memory, some trumped by grislier crimes. Even the allure of the Hollywood-plus-homicide formula can dwindle. I once drove around Beverly Hills with Merv Griffin, who was well steeped in local history and pointed out the so-and-so-lived-here spots, and some sinister ones, like the house where actress Lana Turner’s daughter stabbed and killed her mother’s thuggish boyfriend. How much does that 1958 banner-headline crime resonate with anyone but “murderinos” today?

In its day, the Feb. 1, 1922, unsolved murder of director William Desmond Taylor left Americans both fascinated and morally high-horsing about those sinful Hollywood people.

Taylor — who had ditched his wife, kids, and his original name — was shot to death in his bungalow in the Alvarado Court Apartments at 404 S. Alvarado in the Westlake neighborhood. When the cops arrived, they found, per The Times, Paramount executives and actors and actresses poking through drawers and closets, and the butler washing dishes as the dead man lay on the floor.

Clues and evidence were muddled — some deliberately. The rumor that Taylor was a ladies’ man was possibly floated by studio execs to divert any gossip that Taylor may have been a man’s man — that is, gay. A neighbor glimpsed the likely killer and was convinced it was “a woman dressed up like a man.” That woman may have been the mother of the young silent star Mary Miles Minter, who had a pash for Taylor. For a long while, Taylor’s address was a must-see for the more ghoulishly minded.

For notorious addresses, it’s hard to outdo the Laurel Canyon townhouse on Wonderland Avenue, the site of the July 1, 1981, quadruple murders that birthed movies and TV shows for more than 25 years.

It has a tabloid-magnet, tawdry cast of characters: four people deep into drugs being beaten to death; a porn actor; a drug-dealing, money-laundering nightclub owner and his bouncer; and a witness who was Liberace’s lover and got plastic surgery to look like the campy Vegas performer. The street name is a character, too, and it tees up the easy tropes about the “dark side of Hollywood.”

Porn performer John C. Holmes was acquitted of the murders and then died of AIDS. The nightclub owner, Eddie Nash, was acquitted of murder in a second trial after a bribed juror hung the jury in the first one. But Nash pleaded guilty to federal criminal charges, including conspiracy to murder.

And what kind of neighborhood was this “Wonderland,” where the locals were so used to hearing chaotic noises from the townhouse that when the screaming began at around 4 a.m. on July 1, one neighbor heard screams and saw lights on there, and rather than call police, she turned on her TV to drown out the sound? And another neighbor said with a shrug in his voice, “Who knows who’s been on primal scream therapy or tripping on some drug?” The ugly ’80s in a nutshell.

Scoot ahead to the 1990s, and a man who was renting the place said that “sometimes I sit in my living room and imagine where so-and-so must have died … but I’m getting a $400 break in the rent, so I’m staying put.”

If you’re feeling the springtime itch to go look at open houses, first of all, we’re sorry about the sticker shock. But here’s a primer on the hodgepodge of home styles you’ll see around Southern California.

I don’t have to spend overlong on crimes that are almost as renowned today as they were 55 years ago, when they happened — the Manson family murders. Actress Sharon Tate and three others were killed in a Benedict Canyon house one night, and the next, a married couple were murdered in their Los Feliz home.

The rented Tate house, with its ghastly ghosts, was not put up for sale until 1988, and there was a rumor that Tate’s widower, director Roman Polanski, had offered $1.5 million to bulldoze it. In 1994, an investor did indeed tear down the house and start building a Mediterranean villa. (Soon after, You’ve Got Bad Taste, a store near Sunset Junction, was selling what purported to be pieces of wallboard from the destroyed house.)

The Cielo Drive place has been sold several times since, and the street number changed to wipe the past clean. (There are any number of reasons to change the address of a house — a former president and first lady had three. When Ronald and Nancy Reagan returned from Washington, D.C., in 1989, they had the number of their Bel-Air house changed from the biblically ill-omened 666 to 668 St. Cloud.)

And the street number of the other “Manson murder” house, where Leno and Rosemary LaBianca were slaughtered, was also changed at some point. An Anaheim couple bought the place in the 1980s for tens of thousands of dollars below the value of “comps.”

“Nobody would buy the home because of the killings,” said Tina Yuvienco, the new owner. “We figured it was historical — like the Ambassador Hotel where Robert Kennedy was killed.” The place has sold several times in the last half-dozen years. One real estate agent’s note read, “Do research before showing.”

Winner of the notorious houses stakes for the last 30 years — does “Rockingham” ring a bell? Nicole Brown Simpson and Ron Goldman weren’t murdered at O.J. Simpson’s Brentwood house, but that’s where Simpson ended his melodramatic Bronco chase, where police found a bloody glove, and where guest house guest Kato Kailin heard the three ominous “thumps” on the night of the murders.

For a time there were O.J. tours; you could cruise past his house in a white Bronco. Neighbors were tickled when the house was bought in 1998 and flattened not long thereafter. (That house number, too, was changed.)

In the last house in this part of the column, six people died in one of the biggest firefights in LAPD history. But it’s so far from the glamour-and-gore neighborhoods that it hardly gets a second glance.

It was a little yellow stucco house, and like so many in South L.A. practically elbow-to-elbow with the ones next door. In May 1974, a woman renting the house was offered $100 to let some people stay. “Some people” turned out to be a half-dozen or so members of the SLA, the grandiosely named Symbionese Liberation Army. The urban guerrilla group had kidnapped the teenaged Bay Area newspaper heiress Patricia Hearst three months before, and was on the run.

It didn’t take long before neighbors took notice — one black man leading a group of white people — and one went to the cops. The cops went looking for the SLA, and the battle commenced.

Tear gas started a fire, and the fire blew up some of the thousands of rounds of ammo the SLA had cached in the house. Four of the members died hunkered down inside, and two others died running and gunning as they tried to get away. It was broadcast live on L.A. television.

The address is now a canopied driveway of a large adjacent house.

The glamorous, or a little bit louche

Across the late 19th and into the 20th century, THE “in” address for renowned bohemians and celebrities was a stone house on the lip of the Arroyo Seco. Charles Lummis lived there, a swashbuckling figure whose parties were the Vanity Fair Oscar parties of their day. Lummis was an extraordinary figure — you only had to ask him — but he truly was, an L.A. Times editor, city librarian, pal of Teddy Roosevelt’s, lover, poet, Native American ethnographer, cultural preservationist and founder of L.A.’s first real museum, the Southwest Museum.

Lummis built his house, El Alisal, with rocks dragged out of the arroyo, and opened it for business, the business of entertaining L.A.’s visiting luminaries. In the hundreds of pages of his guest book are signatures, drawings and verses by his guests: John Muir, Dorothea Lange, Douglas Fairbanks, Ida Tarbell, Carl Sandburg, Clarence Darrow, Will Rogers, and the divine Sarah Bernhardt. The slight slope of the concrete floor made it easy to hose the place down after the parties; Lummis called them his “noises.”

Southern California and parts of the Southwest exist as they do today — populous and prosperous — principally because AC made them livable.

The Playboy Mansion, in Holmby Hills, is another 1920s mock-Tudor sprawl whose living adornments, Playboy Playmates, and its testosterone toys, like a game room and the legendary “grotto,” enhanced the reputation of the place and of its lord and master, Hugh Hefner, the founder and publisher of Playboy magazine. A pass to “the Mansion” was an entrée to the Playboy lifestyle, with its hubba-hubba mix of famous men and ornamental women, a place where the word “swinging” was used unironically. I visited the place twice, to interview Hefner, and the second time — which was, as I remember, a few years before Hefner died in 2017 — it struck me as run down, rather grimy and neglected. The city has extended something called a “permanent protection covenant” to the place, which is privately owned and used for business promotions and TV productions.

The closest any house might have come to the world’s conception of Los Angeles in the 1960s converged at a Spanish-style house on North Crescent Heights, home of Dennis Hopper and his wife, Brooke Hayward, an actress and daughter of a rich and troubled family. If you created a Venn diagram overlapping everything that was young and hip and edgy — Hollywood, music, writing, fashion, art — they all converged there, in a bubble-world of boho chic, radical chic, druggy dreams, beauty, daring, and creativity. We shall not see its like again.

The swingingest place of its day — that day being the 1920s — might have been the house at 649 West Adams Blvd., an address that silent movie fans knew because a couple of their favorites lived there.

The house was built around 1905 for businessman Randolph Miner and his wife, a dignified socialite. It was yet another of those mock-Tudor houses that had such a vogue for much too long. Miner’s wife, Zulita, a socialite and arts patron, was a great-great-granddaughter of Jose Dario Arguello, a soldier who led the pobladores to settle Los Angeles in 1781 and was briefly an interim governor of Spanish California.

The couple sought broader social horizons in Europe and around 1917, rented the place to Hollywood’s top vamp, actress Theda Bara. Staid neighbors were there-goes-the-neighborhood shocked. Loose, lurid reports claimed that Bara furnished the house with props befitting her roles, skulls, crystal balls and the like, but a Times story shows her demurely dressed and posing like a house-proud young matron in her new home.

Bara didn’t stay long, and the next resident turned out to be even more notorious, and not by design.

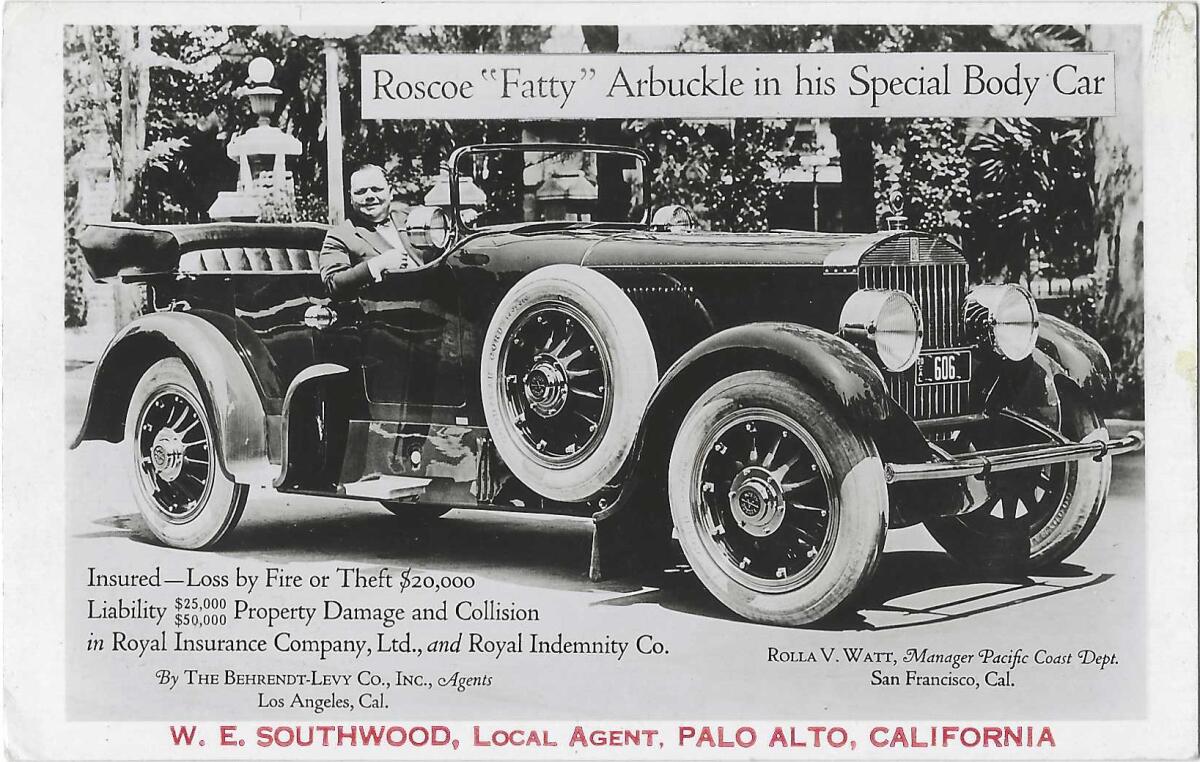

The comedian Fatty Arbuckle was earning $5,000 a week and spending like it was his last paycheck, which, pretty soon, it was. His West Adams parties were legendary for their mayhem and Prohibition booze. In September 1921, he threw a party in San Francisco, and an actress named Virginia Rappe died in the hotel suite. Arbuckle was tried three times for manslaughter, and finally acquitted with an apology from the jury, but his reputation was as dead as Rappe. Thereafter, director Raoul Walsh rented the house for a year or so, followed by Arbuckle’s onetime producer, Joe Schenck, and his wife, the actress Norma Talmadge.

Finally, perhaps exasperated, Estelle Doheny, an ardent Catholic and second wife of oil tycoon Edward Doheny, bought the house to extend their estate. In time, it became a residence for young seminarians and is now part of Mount St. Mary’s campus, on this Boulevard of Broken Dreams and Leases.

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.